Volume 13 Issue 1 *Corresponding author nelsondepaula@yahoo.com.br Submitted 24 Jan 2025 Accepted 21 Feb 2025 Published 25 Feb 2025 Citation PEREIRA, N. P. Sacramento Street (1903): reforms and improvements in light of the Passos Reform in downtown Rio de Janeiro. Coleção Estudos Cariocas, v. 13, n. 1, 2025. DOI: 10.71256/19847203.13.1.128.2025. The article was originally submitted in PORTUGUESE. Translations into other languages were reviewed and validated by the authors and the editorial team. Nevertheless, for the most accurate representation of the subject matter, readers are encouraged to consult the article in its original language.

| Sacramento Street (1903): reforms and improvements in light of the Passos Reform in downtown Rio de Janeiro Rua do Sacramento (1903): reformas e melhoramentos à luz da Reforma Passos no Centro do Rio de Janeiro Calle Sacramento (1903): reformas y mejoras a la luz de la Reforma Passos en el centro de Río de Janeiro Nelson de Paula Pereira1* 1Instituto Universitário de Pesquisas do Rio de Janeiro, R. Joana Angélica, 63 - Ipanema, Rio de Janeiro - RJ, 22420-030, ORCID 0009-0002-0514-9333, nelsondepaula@yahoo.com.br

AbstractThis article examines the first project undertaken by Mayor Pereira Passos: the widening and extension of Sacramento Street (1903) from a historiographical and urbanistic perspective. This project marked the beginning of the urban transformations known as the "Passos Reform," playing a key role in understanding the reforms that shaped Rio de Janeiro throughout the 20th century and reflecting on the patterns and impacts of subsequent urban interventions. The study, based on the analysis of primary and secondary sources, reveals that the urban interventions in Rio de Janeiro, while modernizing, perpetuated inequalities, highlighting the need for reforms that balance modernity, social justice, and urban integration. Keywords: Sacramento Street, Pereira Passos, Urban Reform ResumoEste artigo examina a primeira obra realizada pelo prefeito Pereira Passos: o alargamento e prolongamento da Rua do Sacramento (1903), sob uma perspectiva historiográfica e urbanística. Essa obra marcou o início das transformações urbanas da "Reforma Passos", sendo fundamental para compreender as reformas que moldaram o Rio de Janeiro ao longo do século XX e refletir sobre os padrões e impactos de intervenções urbanas posteriores. O estudo, baseado na análise de fontes primárias e secundárias, revela que as intervenções urbanas no Rio de Janeiro, embora modernizadoras, perpetuaram desigualdades, destacando a necessidade de reformas com modernidade, justiça social e integração urbana. Palavras-chave: Rua do Sacramento, Pereira Passos, Reforma Urbana ResumenEste artículo analiza el primer proyecto llevado a cabo por el alcalde Pereira Passos: la ampliación y prolongación de la Calle Sacramento (1903) desde una perspectiva historiográfica y urbanística. Esta obra marcó el inicio de las transformaciones urbanas de la "Reforma Passos", siendo fundamental para comprender las reformas que moldearon Río de Janeiro a lo largo del siglo XX y reflexionar sobre los patrones e impactos de intervenciones urbanas posteriores. El estudio, basado en el análisis de fuentes primarias y secundarias, revela que las intervenciones urbanas en Río de Janeiro, aunque modernizadoras, perpetuaron desigualdades, destacando la necesidad de reformas que equilibren modernidad, justicia social e integración urbana. Palabras clave: Calle Sacramento, Pereira Passos, Reforma Urbana |

Introduction

The widening and extension of Sacramento Street (1903) was the first major project undertaken by Francisco Pereira Passos, Mayor of the Federal District. This initiative held significant importance for the city of Rio de Janeiro, as it established a connection between Sacramento Street and Camerino Street, the latter also undergoing expansion. Both streets were extended to the new Port of Rio de Janeiro, a large-scale endeavor led by the Federal Government. This strategic road network integration not only facilitated the distribution of goods arriving at the port but also drove a substantial urban reorganization, consolidating the city’s logistical infrastructure and reflecting the modernizing ambitions of the era. This project marked the beginning of a series of urban changes later termed the “Passos Reform.” Its study is crucial as it introduces the theme of urban reforms that profoundly characterized Rio de Janeiro throughout the 20th century. Furthermore, critical analysis of this initiative reveals parallels with subsequent movements of urban transformation.

The primary objective of this text is to conduct a historiographical reflection on the Sacramento Street project within the context of reforms promoted by Pereira Passos. Secondary goals include describing and characterizing the urban transformations driven by this project, analyzing its long-term efficacy, and critically reflecting on Rio de Janeiro’s urban changes, using Sacramento Street as a case study. The methodology involved critical analysis of primary and secondary sources, including books and historical documents from public archives.

The article’s conclusions highlight a recurring reality in Rio de Janeiro’s major urban projects: the persistence of inequality. Despite their integrative and modernizing roles, these interventions also exacerbated the segregation of urban spaces, failing to adequately provide opportunities for the city’s poorer populations. Thus, studying this specific event in the city’s history serves as a critical reflection on urban and social impacts, emphasizing the need for future transformations that balance modernity, social justice, and the preservation of urban identity.

Historical Context

- Rio de Janeiro in Transition to the Republic

With the arrival of the Portuguese Royal Family in 1808, Rio de Janeiro underwent a demographic surge. Approximately 15,000 people migrated from Portugal to settle in a city that previously housed no more than 50,000 inhabitants. The royal family’s relocation imposed new material demands, requiring infrastructure that catered not only to their elite aspirations but also facilitated economic, political, and ideological activities (Abreu, 2006). Between 1808 and 1816, around 750 houses were built—600 within the urban perimeter and 150 in the outskirts. By 1822, the population reached 100,000, rising to 135,000 by 1840 (Benchimol, 1992, p. 319). With this demographic increase, the circulation of goods and the expansion of new occupations and professions also grew.

In the second half of the 19th century, new urban renewal dynamics emerged. Linhares (1979, p. 150) highlights that between 1850 and 1860, a second industrial revolution took shape, driven by steel production and faster transportation systems. This revolution opened new market possibilities, particularly benefiting England, which solidified its position as a global economic power. Meanwhile, the imperial capital lagged in large-scale infrastructure projects to expand its communication networks. Broadly speaking, the city center remained densely populated, with an urban layout reminiscent of the colonial era.

By the early 20th century, Rio de Janeiro’s population continued to grow. Influxes of immigrants and rural workers, including former enslaved people migrating from the declining coffee plantations of the Paraíba Valley, added to the urban fabric. Many sought employment opportunities in the burgeoning port activities. As commerce and manufacturing industries clustered near the Port of Rio de Janeiro, the city’s poorer populations were pushed to reside in the overcrowded center.

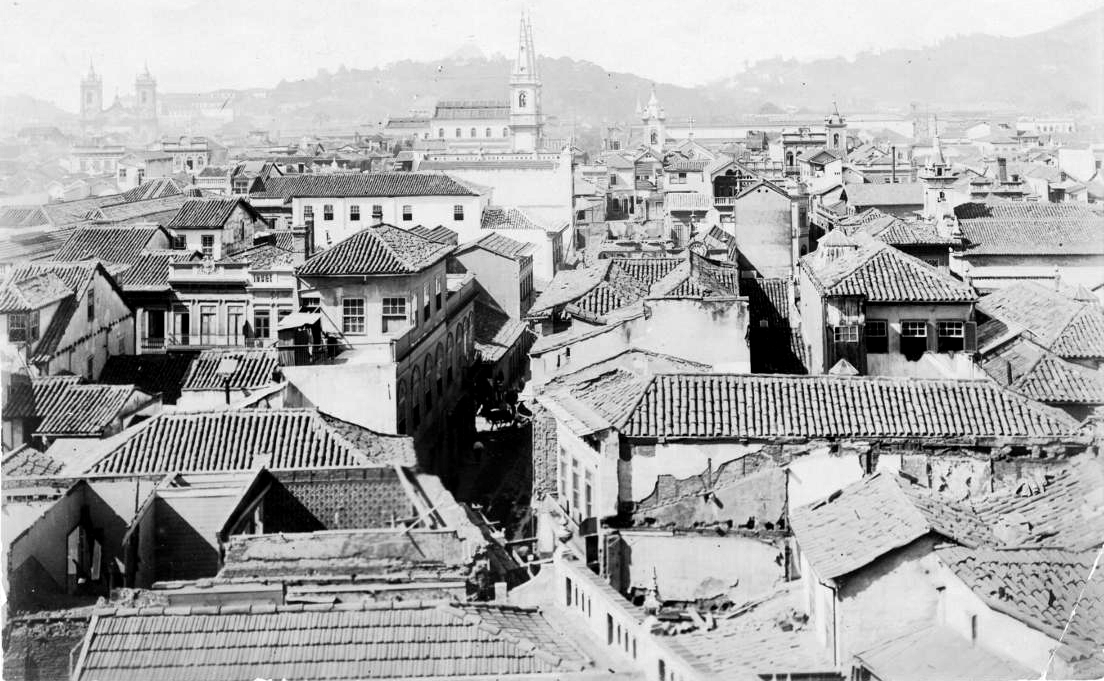

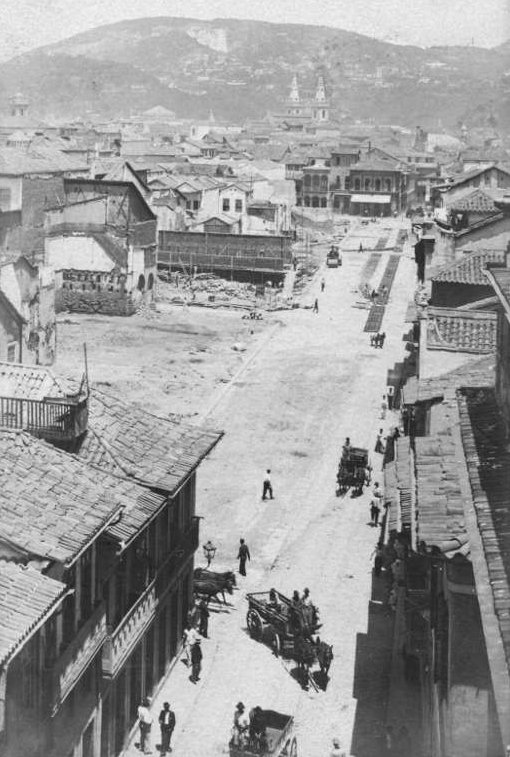

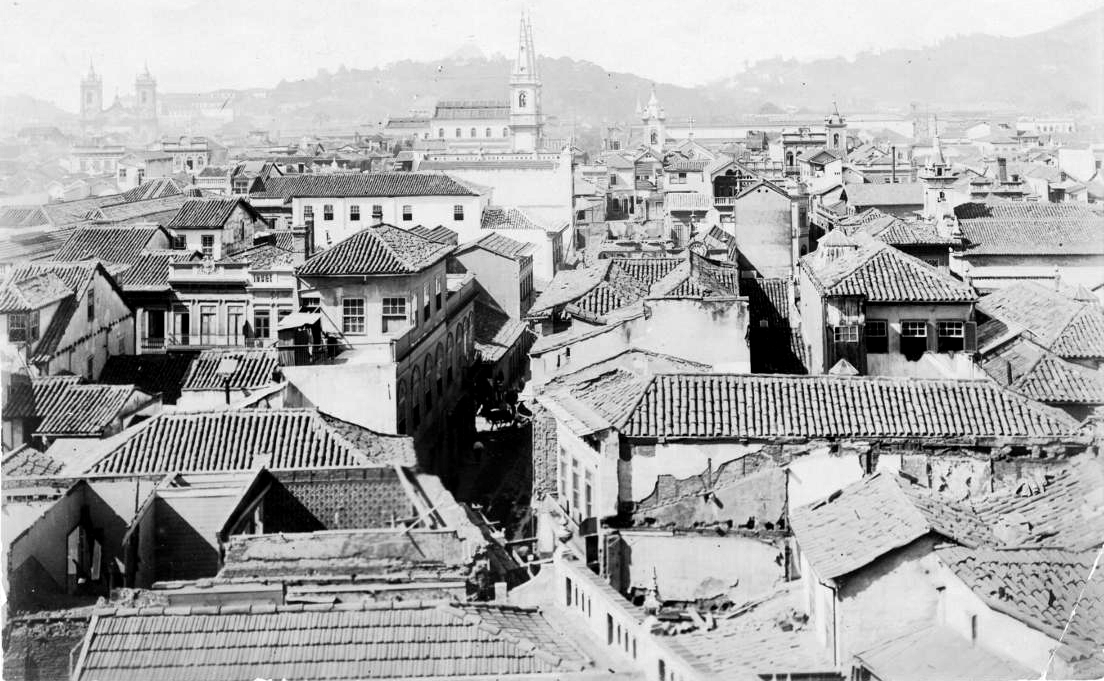

Figure 1: Type of construction in the city before the Urban Reform – Rua da Carioca before the demolitions in 1904.

Source: General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro.

This population crowded into the grand old mansions inherited from the Empire, located in the city center (Figure 1). Due to extreme overcrowding, these buildings had been transformed into sprawling tenements lacking basic hygiene infrastructure or adequate accommodations (Lamarão, 1991, p. 115). Sevcenko (1998, p. 21) notes that moralizing measures—such as bans on religious rituals, singing, and dancing—were imposed on the city’s poor, as if their culture, rather than income inequality, were the root cause of urban disorganization.

The city bore the heavy legacy of the Empire. Slavery had been abolished just 14 years prior; the coffee economy was in decline (Lobo, 1978, p. 171); and diseases like yellow fever, smallpox, and bubonic plague plagued its poorly paved streets. Buildings were low, architecturally incoherent, and topped with aging tile roofs and skylights, while attics and basements teemed with rats and insects (Mathias, 1965, p. 217). The urban poor crammed into collective housing (Figure 2), including tenements, inns, rooming houses, and workers’ villages (Lamarão, 1991, p. 115).

Only 30% of these collective dwellings complied with the legal requirement of providing one latrine facility for every 20 residents (Distrito Federal, 1903a). Some workers living in the center resided in the backyards of the small factories or workshops where they were employed.

Figure 2: Tenement located behind buildings on Mem de Sá Avenue (1906).

Source: General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro.

Furthermore, the term "inn" was often associated with tenements (Backeuser, 1906, p. 105). Carvalho (1985, p. 151) highlights the dual meaning of the term in Aluísio de Azevedo’s novel O Cortiço, reflecting the overlapping realities of urban housing conditions.

- Echoes of Urban Reform in the 20th Century

The Federal Government, under the leadership of President Rodrigues Alves, launched an ambitious campaign for urban reforms in the city, supported by a technical team that included Lauro Müller, Minister of Industry, Transportation, and Public Works; Francisco Pereira Passos, the federally appointed Mayor of the Federal District; Oswaldo Cruz, Director of Public Health; and engineers Paulo de Frontin and Francisco Bicalho. The goal was to transform the old city into a modern metropolis with a renewed vision, drawing inspiration from the urban renovations of Paris, implemented by Georges-Eugène Haussmann, known as Baron Haussmann, who served as Prefect of Paris during the rule of Napoleon III.

Upon taking office as Mayor, Pereira Passos initiated his first major project: the widening and extension of Sacramento Street, carried out between 1903 and 1906. Once expanded, Sacramento Street would connect to another thoroughfare undergoing a similar process, Camerino Street. Both streets were to be extended to the new Port of Rio de Janeiro, a project overseen by the Federal Government. This infrastructure upgrade would ensure that goods arriving at the port could be swiftly distributed throughout the city.

These urban reforms sparked reactions in public opinion, as discussed in the following sections. Nevertheless, within just four years, the capital’s modernization efforts were completed. In this regard, studying these reforms—through contemporary sources and critical analysis from subsequent decades—provides a valuable reference point for understanding the waves of urban transformation that Rio de Janeiro would experience throughout the 20th century. Examining the works on Sacramento Street (1902–1906) offers insight into the city’s drive for urban modernization and the social tensions that, in many ways, persist to this day.

3 Pro-Reform Discourses

Narrow, poorly paved, and unclean streets, along with deteriorating mansions inherited from the Imperial era, housed rooming houses, inns, and tenements, many of which operated behind commercial establishments. Such was the landscape of Rio de Janeiro before the Urban Reform of 1902–1906. Additionally, the coffee industry in the Paraíba Valley was in decline.

According to Lobo (1978, p. 171):

[...] In the years 1888 and 1889, a radical transformation in the credit system took place, shifting away from serving almost exclusively the interests of coffee production and trade; the plantation economy of the Paraíba Valley entered an irreversible decline; the emancipation of enslaved people disrupted the labor system; and there was a modification in the political model.

The 1907 Census, conducted by the government at the request of Minister Lauro Müller, provides insight into Rio de Janeiro’s industrial sector and workforce. At the time, the city housed 745 factories of various types, employing a total of 21,416 workers (Lobo, 1978, p. 577-579).

Epidemics claimed many lives each year. In 1870, yellow fever caused 1,118 deaths, rising to 3,659 in 1873 and 3,476 in 1876. As a result, debates surrounding the city’s sanitation became increasingly urgent.

- The Medical Discourse

The primary advocates for urban sanitation were physicians, who proposed:

[...] Irrigation and cleaning of streets and public squares; dispersion of ships docked in the port; relocation of immigrants beyond the city and municipal limits; establishment of parish commissions to aid epidemic victims; opening of Santa Isabel Hospital; inspection of tenements to either remove them or reduce their occupancy; and public advisories on hygiene and living conditions. (Benchimol, 1992, p. 137)

Most epidemic victims resided in the neighborhoods of Gamboa, Saco do Alferes, and Saúde. Overcrowding was one of the key factors exacerbating the spread of disease, with tenements being singled out as major sources of contagion. As early as 1843, during a scarlet fever outbreak, the Imperial Academy of Medicine recommended avoiding the overcrowding of housing units (Abreu, 1985). By the late 19th century, the situation had become untenable.

Dr. Atalipa de Gomengoro stated (Benchimol, 1992, p. 137):

[...] Disperse the residents of the infected neighborhood; enter those filthy tenements [...] where dozens of individuals live in spaces with air capacity sufficient for only six or eight, and scatter them, spread them out, force them to breathe an adequate supply of air.

In 1886, the Superior Council of Public Health expressed its stance on the city's sanitary issues (Leeds & Leeds, 1978, p. 189):

[...] All lamenting the conditions of the tenements and agreeing that such housing posed severe health risks, concluding that the residents should be relocated to the outskirts of the city, near train and tram lines. Reports pressured the government to expropriate and demolish the tenements and build individual houses for the poor.

Only Barata Ribeiro took initial steps to implement these recommendations by combating the spread of tenements, marking the beginning of state intervention in the city’s sanitary policies.

In September 1889, the Second Brazilian Congress of Medicine and Surgery took place, where several sanitary measures for Rio de Janeiro were approved. The central area was identified as the epicenter of epidemics, leading to the following proposals: draining and reclaiming low-lying, swampy land; standardizing the potable water supply; channeling rivers, streams, and ditches; preserving forests; conducting a rigorous review of sewage system construction, including ventilation and offshore discharge; properly disposing of city waste; paving and washing streets daily; widening and extending roads to allow for better air circulation through sea breezes; passing a law to support companies in building hygienic housing for the poor; and granting sanitary authorities greater autonomy. Despite these efforts, epidemics continued to claim thousands of lives, disproportionately affecting those living in the central districts.

- The Engineers’ Discourses and the Commission for the Improvement of Rio de Janeiro

Another group that stood out in advocating for urban reforms was the engineers. In 1874, they proposed a comprehensive urban plan through the Commission for the Improvement of Rio de Janeiro, which included Jerônimo R.M. Jardim, Marcelino Ramos da Silva, Francisco Pereira Passos, and later, João Alfredo.

In 1875, an exhibition showcasing public works projects was inaugurated. Among these projects, 22 of the presented were improvements to existing ports across Brazil, canal constructions, river enhancements, hydrographic charts, bridge designs, railway constructions such as the Madeira-Mamoré Railway, roadways, telegraph lines, geographic and topographic maps of Brazil’s borders, and scientific studies like the flora of the Amazon. Many of these projects never materialized, and those that did were executed by foreign companies. These proposals were part of the First Exhibition of Public Works, which was preparing for the Universal Exposition.

In addition to the Commission’s projects, the exhibition featured plans for three tunnels through the Livramento and São Bento hills, as well as a submarine railway tunnel connecting Praça XV to Niterói (preceding the proposal for the Rio-Niterói Bridge). The Commission also planned the construction of public buildings, such as the Inspectorate of Public Works, designed by Francisco Pereira Passos; the Telegraph Office; the Fire Department Headquarters; and the reconstruction of the Fluminense Club at Praça da Constituição (now Praça Tiradentes) — also a project by Francisco Pereira Passos.

On January 12, 1875, the Commission’s rapporteur submitted the project, which outlined (Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, 1875):

It was our duty to designate the width of sidewalks and lateral walkways in new streets and squares, as well as the height of continuous arcades or porticos, [...] to indicate which streets should be opened, widened, or straightened, [...] the draining of lands and filling of swamps, and to establish essential rules for the construction of dwellings.

Squares and new streets were to be opened or aligned to ensure air circulation throughout the city. Ventilation and circulation were deemed essential for public health and the efficient movement of goods from the Port of Rio de Janeiro. The project encompassed central neighborhoods (in part), Engenho Velho, Andaraí, São Cristóvão, Catete, and the present-day Botafogo district.

The Mangue Canal was one of the Commission’s focal points, with plans to extend it from the base of the Andaraí hills to the sea. Along the canal, rainwater and swamp runoff would be channeled into a basin near the current Barão de Mesquita Street and Boulevard 28 de Setembro. A system of locks would create varying water levels, enabling navigation and recreational use.

Among the urban planning influences, the reforms of Paris under Georges-Eugène Haussmann, Prefect of Paris during Napoleon III’s reign, stood out. However, unlike Paris, where avenues and streets were carved through the city center, the Commission proposed opening them in peripheral areas to encourage settlement. The Mangue Canal served as the axis around which streets and avenues would be opened and aligned.

The engineers of the Commission for Improvement emphasized in their report (Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, 1875):

One of the most notable flaws in the older part of the city is the narrowness and excessive curvature of its streets, which not only hinder the circulation of vehicles and pedestrians but also significantly impede the renewal of air, which becomes stagnant due to various factors within dwellings. In planning the streets of new neighborhoods, the Commission prioritized avoiding this issue, designing streets with widths far exceeding the norm in Rio de Janeiro.

The Commission’s report highlighted several projects, including the opening of an avenue connecting Campo da Aclamação (now Praça da República) to the base of the Andaraí hills. This avenue would be 40 meters wide, with 18 meters for the roadway and 11 meters for tree-lined sidewalks on both sides. Its extension to Portão Vermelho Street (now Pinto de Figueiredo Street) would span 4,780 meters (Gerson, 2000, p. 357). Near Travessa da Babilônia, the avenue would intersect with another, linking Andaraí Pequeno Street (now Conde de Bonfim Street) to the lands designated for the Zoo (in Vila Isabel) and the botanical garden, following the extension of Boulevard 28 de Setembro.

From the extension of Boulevard 28 de Setembro, which ran from the Portão da Vila Isabel to São Cristóvão Street, another avenue would be constructed. In São Cristóvão, an avenue 40 meters wide would extend from the Portão da Coroa to Engenho Velho Street, crossing the canal and reaching Campo de São Cristóvão. Engenho Novo Street (Gerson, 2000, p. 421) was one of the longest in the North Zone, beginning at Largo do Pedregulho. After the death of nurse Ana Néri, the street was renamed Ana Néri Street.

The area now known as Praça da Bandeira was then called Matadouro (Slaughterhouse). This space was slated for a large park dedicated to exhibiting industrial machinery and equipment.

Between Ilha dos Melões and Ilha das Moças, a dock was planned from Ponta da Chichorra to Praia dos Lázaros. The Saco de São Diogo would be filled in to build a maritime station for the Dom Pedro II Railway. The station would streamline cargo transport, which was previously bottlenecked through Rio de Janeiro’s narrow streets. Across the reclaimed land, numerous streets were planned for commercial and industrial buildings, along with a chapel and a market square.

The Commission proposed appointing an engineer or architect to oversee construction standards in each city district, following the English model of district surveyors.

All these projects were to be carried out by the government, but they came at a staggering cost — approximately 32,000,000$000. When adjusted to present-day values, this amount would reach around R$ 4,000,000,000.00 (Diniz, 2022), an equally significant sum. As a result, the report suggested outsourcing the execution of these works to a competent company. Luís Raphael Vieira Souto criticized the Commission’s report, as its efforts were limited to the neighborhoods of Andaraí, Engenho Velho, and São Cristóvão, neglecting the city center (Lamarão, 1991, p. 75), where:

[...] streets are narrow, winding, and poorly ventilated [...], houses are cramped [...], lacking light and airflow [...]; here, the beaches demand docks, the swamps cry out for landfill, the streets need air, and the squares require trees and pavement; it is in the city center [...] that the heart of our commerce urgently calls for improved public roads, which currently cause such traffic chaos.

Of all the Commission’s proposals, only the railway branch and maritime station were realized—thanks to the initiative of Francisco Pereira Passos.

- The government’s stance

Yellow fever and the thousands of deaths it caused annually led the Imperial Government to appoint a medical commission to work alongside the Central Board of Public Hygiene in reviewing sanitary measures. In 1876, the Board submitted a proposal to the Municipal Chamber, asserting that collective housing was the primary source of epidemic outbreaks. It recommended the construction of affordable housing for poor families (General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro, 1875–1876). However, the Board faced resistance from the Municipal Chamber.

Between 1882 and 1883, the fight against tenements was carried out by the Board of Public Hygiene, as reported by Luís Raphael Vieira Souto (General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro, 1882–1883).

- The Housing Construction Companies for Workers

In 1882, through Legislative Decree 3151 of December 9, 1882, the government granted private companies the right to build affordable housing for poor families. The first to submit proposals were Felicíssimo Vieira de Almeida, Antônio José Rodrigues de Araújo, and Lourenço Ferreira da Silva. Later, Luís Raphael Vieira Souto and Antônio Domingues dos Santos Silva presented an additional proposal (Lamarão, 1991, p. 75). These concessions were incentivized through exemptions from import duties on construction materials and additional tax benefits for the companies. However, due to the Encilhamento financial crisis, most of these concessions failed to move forward with their projects.

One particularly significant company was Arthur Sauer’s Companhia de Saneamento do Rio de Janeiro. According to Benchimol (1992, p. 159):

The company was required to provide free gas or electric lighting in common areas, employ staff to maintain order and upkeep, assign one or two doctors to care for tenants' health (and submit biannual reports to the General Hygiene Inspectorate), and even establish mixed-gender elementary schools.

A year after the Proclamation of the Republic, Arthur Sauer presented a list of planned housing developments: Vila Rui Barbosa was to be built at the corner of Rua dos Inválidos and Rua do Senado; Vila Arthur Sauer was planned behind the Botanical Garden, on Rua Dona Castorina, next to the Fábrica de Tecidos Carioca textile factory; Vila Senador Soares was to be built on Rua Gonzaga Bastos, in Vila Isabel, an area that already housed Fiação e Tecidos Confiança Industrial and later the Fábrica Cruzeiro; on Rua Maxwell, beside the Fábrica de Tecidos Confiança, Vila Maxwell was to be constructed; in Sampaio, across from the train station on Rua 24 de Maio, Vila Sampaio was planned; Vila Fróis da Cruz was to be built on Rua São Clemente; Vila Mangueira was to be developed near the Mangueira Train Station; Vila Carvalho near the São Francisco Xavier Train Station; Vila Rocha on Rua Ana Neri, across from the Rocha Train Station; Vila Riachuelo on Rua 24 de Maio, near the Engenho Novo Train Station; and finally, Vila Carolina and Vila Vieira de Castro, also near the Engenho Novo Train Station.

During the Republican period, numerous conflicts arose between the Companhia de Saneamento and the new Republican Government, which now required the payment of customs duties, significantly increasing the cost of importing construction materials — previously exempt under the Imperial government. Additionally, critics argued that these houses primarily benefited workers from the textile factories, while the vast workforce of the city center remained excluded from these housing initiatives.

- The Chroniclers and the Press

Another group that played a key role in the pro-reform debates of the city was the press. At the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, new printing techniques emerged, reducing newspaper costs and making them more accessible to a broader segment of society.

Several notable figures advocated for urban change aimed at improving the city’s sanitation. Among them were José do Patrocínio and his newspaper Cidade do Rio; Rui Barbosa, through his articles in the press; Edmundo Bittencourt and Leão Veloso in Correio da Manhã; Alcindo Guanabara, Medeiros e Albuquerque, and João Lage in O Paiz; Olavo Bilac in Gazeta de Notícias; Figueiredo Pimentel in O Binóculo and Revista Kósmos; and José Carlos Rodrigues in Jornal do Comércio.

For Olavo Bilac, it was necessary to demolish the old city and bury its traditional ways of life so that a new city, more fitting of a capital, could emerge (Pechman, 1985, p. 134).

Figueiredo Pimentel was one of the key figures in promoting a new urban civilization, fostering new forms of sociability. He proposed and encouraged events such as the Batalha das Flores (Battle of Flowers), which took place during Pereira Passos’ administration; the carnival parades (corsos) in Botafogo and Avenida Central; the Flamengo "footing" (a fashionable promenade); the five o’clock tea; the dog exhibition; the Mi-Carême (a mid-Lent celebration); and the Ladies’ Club.

The Predecessors of Pereira Passos

Despite the financial difficulties faced by Rio de Janeiro, several mayors made brief attempts to address the city’s sanitation and hygiene problems. Pinheiro (1977, p. 8–11) summarizes the key figures:

Barata Ribeiro governed for about five months but initiated an important campaign to eradicate tenements. A pediatrician recognized by the Rio de Janeiro School of Medicine, his measures caused significant dissatisfaction among business owners and landlords. His project closely resembled the urban reforms that Mayor Francisco Pereira Passos would later implement in the city.

As part of his plan, Barata Ribeiro decreed the setback of buildings on streets that would later be widened to accommodate the growing flow of passengers and cargo, particularly from the Port of Rio de Janeiro and Dom Pedro II Station.

Benchimol (1992, p. 183) highlights an episode that sparked significant protests when Barata Ribeiro ordered:

[...] the demolition of the inn known as “Cabeça de Porco,” located at Rua Barão de São Félix, No. 154. On January 21, 1863, he issued a notice to the inn’s owners, granting them five days to begin demolition—under penalty of having the work carried out by the city at their expense.

This demolition was not peaceful; the police had to intervene. The event was so controversial that during Pereira Passos’ administration, the city was forced to compensate the property owner for damages (Benchimol, 1992, p. 184).

Colonel Henrique Valadares, a military engineer, replaced Antônio Dias Ferreira, a physician whose appointment had been rejected by the Senate. He formalized the bureaucratic structure of the city government through Organic Law No. 85 of September 20, 1882, creating new services and stabilizing municipal finances.

During the Provisional Government, Félix da Cunha took over the city’s administration. His tenure saw the renewal of tramway contracts, extension of tram lines into distant neighborhoods, and the excavation of the first tunnel to Copacabana—the Barroso Tunnel, later known as Túnel Velho and subsequently Túnel Alaor Prata. In 1892, Rio de Janeiro’s first electric tram was inaugurated. His administration also oversaw the demolition of elevated walkways over Rua da Misericórdia and Rua Sete de Setembro, which had once connected the Paço Imperial to the Imperial Chapel and the Carmo Convent.

Francisco Furquim Werneck de Almeida, a physician appointed by President Prudente de Morais, formed a commission to improve the city’s sanitation. However, due to his ties to Francisco Glicério, an opposition figure, he was dismissed. His administration focused on sanitation and hygiene issues, addressing deficient water supply, waste removal, and improving hygiene conditions in municipal schools. He also enforced the maintenance of deteriorating buildings, improved the paving of streets and squares, modernized the slaughterhouse, and regulated meat distribution. He was briefly succeeded by Joaquim José da Rosa, also a physician.

Ubaldino do Amaral Fontoura, a lawyer, did not undertake public works due to severe financial constraints. However, he carried out an administrative reform, eliminating several municipal positions. Luiz Van Erven, an engineer, briefly served as mayor but limited himself to administrative duties. José Cesário de Faria Alvim, a lawyer, was unable to implement any reforms due to an economic crisis. Honório Gurgel do Amaral also served as interim mayor. Antônio Coelho Rodrigues, a lawyer, inaugurated the statue of Pedro Álvares Cabral in Glória but failed to restore municipal finances.

João Felipe Pereira, a civil engineer, inherited severe financial difficulties from his predecessors, including an 11-month backlog in municipal employee salaries. To address this, he suspended construction projects, dismissed staff, and reorganized municipal finances, successfully restoring on-time salary payments. He also revamped the Land Registry Service, tackled waste management by improving waste disposal and incineration, blocked fare increases on tramways, and approved a project granting a monopoly to the Santa Casa, which significantly raised burial fees. Additionally, he ordered the removal of horse-drawn carriages from a seized stable at the corner of Rua Visconde do Rio Branco and Avenida Gomes Freire, a location believed to be where Tiradentes was hanged and where Pereira Passos later built the Escola Municipal Tiradentes. On October 5, 1900, he decreed the demolition of Morro do Senado, using the excavated soil to fill swampy land along the Mangue Canal and Ilha das Moças in São Cristóvão.

Joaquim Xavier da Silveira, a lawyer, faced municipal hardships but managed to complete several projects, including the construction of Cais Pharoux in Praça XV. During his tenure, Ipanema received electric lighting, and the statue of Visconde do Rio Branco was inaugurated. The next interim mayor was Carlos Leite Ribeiro, a colonel in the National Guard. In the forty days he held office, he implemented several improvements, including paving Rua do Ouvidor and modifying public health and safety regulations. He also initiated the beautification of public spaces and drafted a law that would grant the next mayor increased autonomy — a position soon to be assumed by Francisco Pereira Passos.

The Works on Sacramento Street: The Beginning of the Passos Reform

- The Presidential Context of the Republic

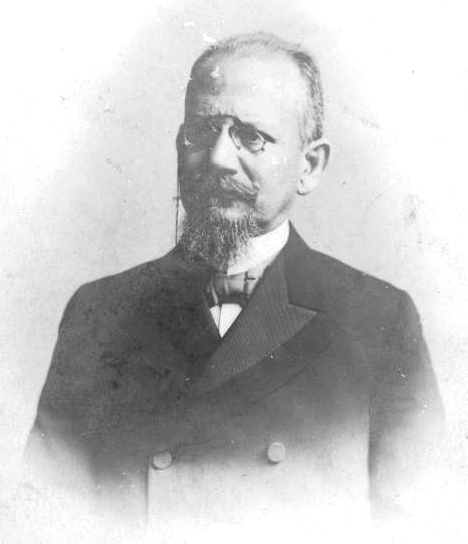

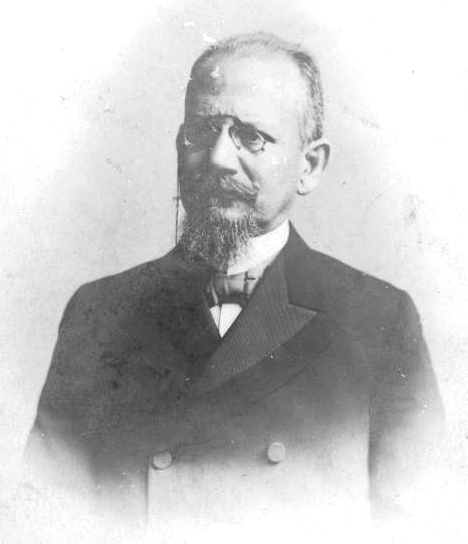

In 1902, Francisco de Paula Rodrigues Alves (Figure 3) assumed the Presidency of the Republic of Brazil. At that time, Rio de Janeiro was a city filled with narrow, dark, dirty, and poorly ventilated streets.

The Administrative Center of Rio de Janeiro was confined between the city's main hills: São Bento Hill, home to the Benedictines; Castelo Hill, where the city was founded and where the Jesuits resided for a significant period in Rio de Janeiro’s history; Santo Antônio Hill, where the Franciscan Monks were based; as well as Senado Hill and Conceição Hill.

The political-administrative agenda of Rodrigues Alves focused on two key points: the remodeling of the capital and immigration policy (Rocha, 1985, p. 58).

Jornal do Brasil published in its November 15, 1902 edition:

Rodrigues Alves promises to prioritize Rio – Jornal do Brasil. 11/15 – Rodrigues Alves assumes the presidency of Brazil after defeating Quintino Bocaiúva, winning 316,248 votes against 23,500 in the March 1 election. A native of São Paulo, the new president promised to focus almost exclusively on Rio de Janeiro. “I will dedicate myself almost exclusively to the sanitation and improvement of the port and the city of Rio de Janeiro,” he declared before boarding the train that would bring him to the capital. Rodrigues Alves, who appointed Pereira Passos as Mayor of Rio, aimed to completely change how foreigners perceived the city. “The capital cannot continue to be regarded as a city of hardship when it possesses abundant resources to become the most remarkable hub of labor, activity, and capital in this part of the world,” he stated during his inauguration ceremony. While Rodrigues Alves was met with applause for his speech in defense of Rio, his predecessor, Campos Sales, was booed as he departed the city for São Paulo, taking a train from Estação Central.

Rodrigues Alves did not view Urban Reform as merely a beautification project. He was convinced that the transformation and sanitation of Rio de Janeiro were matters of national interest, essential for the country's overall development.

Figure 3: Francisco de Paula Rodrigues Alves.

Source: Historical Archive of the Museum of the Republic.

- The Team Behind the Urban Reform

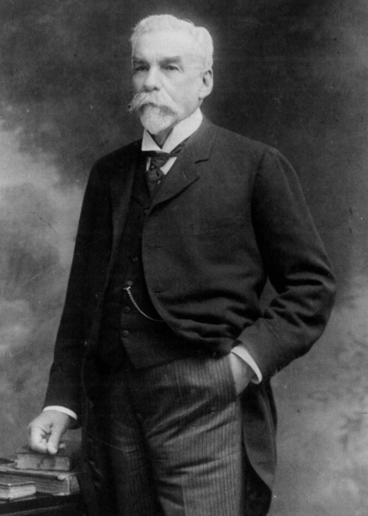

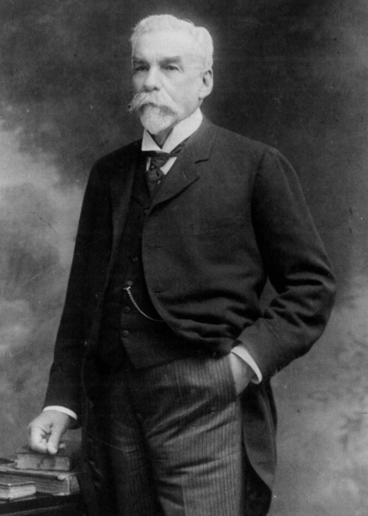

The team responsible for Rio de Janeiro’s major transformation included: President Rodrigues Alves; Minister Lauro Müller; physician Oswaldo Cruz; engineers Paulo de Frontin and Francisco Bicalho; and the Federal District Mayor, Engineer Francisco Pereira Passos (Figure 4).

In his inaugural speech (Câmara dos Deputados, 1978), Rodrigues Alves emphasized a series of public works for Rio de Janeiro. The federal government would oversee: the construction of the Port of Rio de Janeiro’s docks, the completion of the Mangue Canal, the demolition of Morro do Senado, and the opening of a grand avenue (Avenida Central) cutting through the city from sea to sea—projects assigned to engineers Francisco Bicalho and Paulo de Frontin. The Federal District Municipality would handle: the opening of Avenida Beira-Mar, a new avenue connecting Passeio Público to Largo do Estácio, the widening and extension of streets, and the creation of streets, avenues, and squares—all necessitating the demolition of tenements (cortiços), rooming houses, inns, and unsanitary structures. Physician Oswaldo Cruz was tasked with addressing public health crises, particularly epidemics that claimed thousands of lives and deterred immigrants.

To manage these projects, Paulo de Frontin—President of the Clube de Engenharia in 1903 — established criteria for awarding contracts. This required amending the Imperial Decree 816 of July 10, 1855 (on expropriations) through Decree 1021 of August 25, 1903.

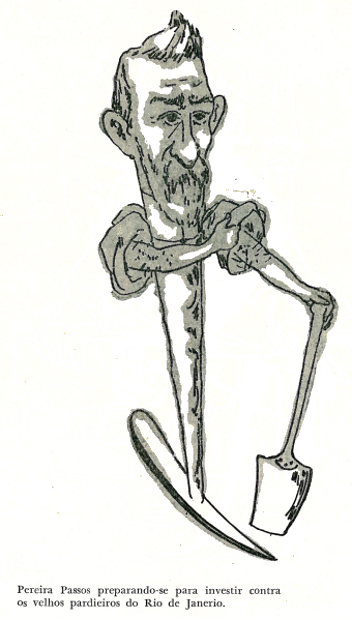

Figure 4: Francisco Pereira Passos (sem data).

Source: General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro

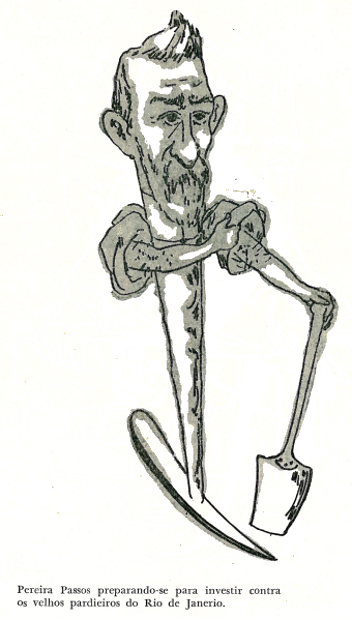

Team members were chosen for their expertise. However, the most drastic reforms fell to Oswaldo Cruz (Carvalho, 1988, p. 99), the renowned sanitarian who enforced mandatory vaccination (Benchimol, 1992, p. 296), and Pereira Passos, who spearheaded socially and urbanistically impactful public works. Consequently, Cruz—the “mosquito-slaying general”—and Passos—nicknamed “bota-abaixo” (“the demolisher”)—became targets of criticism from opponents of Rio’s new policies (Figure 5).

Upon assuming the mayoralty, Pereira Passos took several actions (Athayde, n.d.): he audited municipal finances; settled all outstanding debts—some dating back to 1897; dismissed unnecessary employees; prohibited the sale of lottery tickets on streets; banned uncovered food trays; barred dairy cows from roaming and being milked at customers’ doors; outlawed pig farming within the Federal District; forbade displaying meat on doors or on dirty, old cloths in butcher shops; terminated an outdated street-paving contract and implemented an improved paving system for streets, squares, and roads; established vehicle weighing services; criminalized begging; ordered the removal of stray dogs; removed church railings; regulated new building constructions; extended the Pharoux Quay; opened bids for school buildings; mandated the cleaning of property facades; corrected street alignments, extended streets, opened avenues, built squares, and prolonged Sacramento Street (now Passos Avenue) to align with Empress Street (now Camerino Street). The intense work of his administration’s first months often relied on enforcing existing but previously ignored laws.

Figure 5: Caricature from 1903, criticizing Pereira Passos for the demolition of the city's old buildings.

Source: Mathias (1965, p. 223)

Facing criticism, Passos was condemned by institutions that had once advocated for urgent urban reform. The Academy of Medicine labeled him the “Municipal Cyclone.” Senator Ruy Barbosa argued that demolitions would lead to ruins, doubting resources and capital for proposed new constructions.

By mid-1903, key projects were underway, including studies and plans to extend Sacramento Street as part of the city’s improvement agenda.

- The Parish of Sacramento

The parish (Figure 6) derives its name from the church of the same name, established in 1826 and divided into three districts by the City Council in a session on January 28, 1833. However, the origins of the church trace back to the ancient Irmandade do Santíssimo Sacramento (Brotherhood of the Blessed Sacrament), founded in 1734 at the Igreja do Rosário (Rosary Church), where it remained until the chapter relocated to the Carmelite temple, as the church on Rua Direita (now 1º de Março Street) lacked adequate space. After multiple relocations (Maurício, 1977, p. 221), the brotherhood obtained a license on March 1, 1816, to build a church on a plot measuring 14½ braças (approximately 32 meters) in frontage and 28 braças in depth, purchased from Colonel José de Souza Meirelles on Rua Real Erário, later renamed Moeda Street and then Sacramento Street. This land was part of Campo da Polé, a swampy area from which a large ditch ran through Largo do Rocio (now Praça Tiradentes) and ended at Rua dos Inválidos and Rezende Street. Construction began on April 23, funded by the brotherhood and government lotteries. The church’s images were transferred to the main chapel in July 1820 after its consecration. The church was dedicated by Bishop Conde de Irajá on June 30, 1857, but final works concluded only in 1875.

Figure 6: Map of the Parishes of Rio de Janeiro, highlighting the Central Parishes. The Parish of Sacramento is marked in red.

Source: Pereira Passos Municipal Institute of Urban Planning.

Built on Sacramento Street, the church featured a marble mosaic-floored atrium surrounded by an iron railing (Seara, 2004, p. 86), later removed during Pereira Passos’s urban reforms to widen the street. Its interior included woodcarvings by Antônio de Pádua e Castro and oil paintings. It housed the oldest baptismal font in Rio (Seara, 2004, p. 87). Designed by João da Silva Muniz, the church was consecrated in 1859. Its two spired towers, part of José Bittencourt da Silva’s design, were completed in 1875 (Seara, 2004, p. 87).

Figure 7: Sacramento Street: Panoramic view towards Praça Tiradentes before the extension works (1903).

Source: Historical Archive of the Museum of the Republic (photograph by Augusto Malta)

The parish was characterized by narrow, winding streets (Figure 7), most predating the transfer of Brazil’s capital from Salvador to Rio. By 1840, it was the city’s most populous parish, bordering the Candelária Parish and serving as a hub for import-export commerce. Key institutions in the Parish of Sacramento included: the National Treasury and Federal Revenue Office on Sacramento Street; the Court of Accounts, National School of Fine Arts, and National Music Institute on Luiz de Camões Street; the Polytechnic School and the Ministry of Justice headquarters at Praça Tiradentes; the Portuguese Reading Room on Luiz de Camões Street; the Commercial Employees’ Association building on Gonçalves Dias Street; theaters such as São Pedro de Alcântara, São José, Maison Moderne (Praça Tiradentes), Lucinda, Carlos Gomes, and Recreio Dramático on Luiz Gama Street (now Carioca Street).

The Polytechnic School, originally the Central School, opened on April 25, 1874, and became the birthplace of the Clube de Engenharia (Engineering Club), founded on December 24, 1880. The club included alumni such as Francisco Pereira Passos, Conrado Niemeyer, Paulo de Frontin, Belford Roxo, Carlos Sampaio, Vieira Souto, and Francisco Bicalho, later playing a pivotal role in urban reform debates (Carvalho, 1985, pp. 42-43). The National School of Fine Arts was established by the Count da Barca in 1826.

The Ministry of Justice building, formerly the Imperial Secretariat, belonged to the Baron do Rio Seco and later the Baron da Taquara before being acquired by the government in 1876. It also housed the Club Fluminense, a recreational society.

At Praça Tiradentes, the Tipográfica do Brasil building hosted the Sociedade Petalógica, where poets and intellectuals like Justiniano José da Rocha, Alves Branco, Eusébio, Honório Carneiro Leão, and José Bonifácio debated independence. The society met in a building owned by Francisco de Paula Brito, who operated a paper, wax, and tea shop there starting in 1831. The site also housed a printing press for political periodicals and became a gathering place for Romantic-era poets, including Gonçalves Dias and Porto-Alegre. Paula Brito, a key figure in the city, was born on December 2, 1809, and died on December 15, 1861.

The parish contained seven public buildings, 3,274 private buildings, 11 churches, six barracks, five hospitals, and 5,788 households. The Parish of Sacramento accounted for 8.8% of the city’s free male population and 9.8% of its female population (Benchimol, 1992, p. 92). It was a vital center for cultural and commercial activity.

Vaz (1985) compiles statistics for the parish from multiple sources (Pimentel, 1880; Ibituruna, 1886; Carvalho, 1897) in Tables 1, 2, and 3. The data reveal stark contrasts due to the precarious state of collective housing. Notably, Pimentel (1890) found that only 11% of residences in the parish met good hygienic standards, while 67% were classified as unsanitary — a deeply alarming figure.

Table 1: Number of Tenements, Rooms, Inns, Location, and Population in the Parish of Sacramento

Year | Inns or Tenements | Rooms or Houses | In-habitants | Inhabitants per Inn | Inhabitants per Room | Rooms per Inn |

1869 | 31 | 491 | 693 | 22,3 | 1,4 | 15,8 |

1888 | 74 | 1201 | 1818 | 24,5 | 1,5 | 16,2 |

Source: Vaz (1985, apud Pimentel, 1890).

Table 2: Number of Tenements and Rooms in the Parish of Sacramento

Year | Number of Inns | Rooms |

1884 | 111 | 1992 |

Source: Vaz (1985, apud Ibituruna, 1886).

Table 3: Evolution of the Number of Collective Dwellings per Year in the Parish of Sacramento

Year | Number |

1869 | 31 |

1884 | 111 |

1888 | 74 |

1895 | 59 |

Source: Vaz (1985, apud Pimentel, 1880, Ibituruna, 1886, and Carvalho, 1897, p. 17).

- Sacramento Street Before the Transformations

The street began at Praça Tiradentes (formerly Largo do Rocio) and extended to São Joaquim Street, facing the Igreja de São Joaquim, which was expropriated for street extension and alignment. Originally named Lampadosa Street (in honor of the Church of Our Lady of Lampadosa, which preceded the Church of the Blessed Sacrament), it was later renamed Erário Street after the National Public Treasury headquartered there (Sodré, 1906), before adopting its current name during the reforms. Notably, the present-day Church of Lampadosa is not the original structure but a 20th-century replacement built in Mexican Neo-colonial style on the same site.

The old street served as the sole east-west thoroughfare connecting the city’s eastern zone to the hinterland, the plantations of Engenho Velho, and the Santa Cruz Estate. It intersected key streets: Alfândega Street, General Câmara Street, São Pedro Street, Teophilo Ottoni Street, and Larga de São Joaquim Street. Its opening facilitated mobility for residents of Largo do Rocio and surrounding areas (Lavradio Street, Constituição Street, Frei Caneca Street).

Cavalcanti (1878) describes prominent buildings on Sacramento Street at the time (Table 4). He notes that, in 1878, the street included 11 single-story townhouses, 7 two-story townhouses, and 19 ground-floor buildings—reflecting dense population clustering in a compact area.

Table 4: Owners of the Main Properties on Sacramento Street in 1878

Owner | Building Number |

Santa Casa | 9 and 33 |

Church of Lampadosa | No number (S/Nº) |

National Public Treasury | 17 |

Banco Industrial | 2 and 4 |

Church of Sacramento | 28 |

Source: Cavalcanti (1878).

By the end of the monarchy, Sacramento Street housed the Ministry of Finance (Gerson, 2000, p. 196). It was a route for many processions, and at its corner with Largo do Rocio (now Praça Tiradentes), a portable pulpit was erected where a priest addressed crowds by torchlight and candlelight. These processions, typically held at night, saw worshippers praying for divine protection against yellow fever epidemics (Gerson, 2000, p. 120). The street was also home to José Bonifácio’s residence (1822), the Embassy of Morocco, the Shah of Persia (Gerson, 2000, p. 116), the Casa dos Pássaros (House of Birds), the Sociedade Auxiliadora da Indústria Nacional (National Industry Aid Society), the Instituto Histórico e Geográfico (Historical and Geographical Institute), judicial offices, and the Public Archives (Gerson, 2000, p. 191). At number 35, a butcher shop owned by Jacintho Plácido Corrêa once operated (Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, [n.d.]).

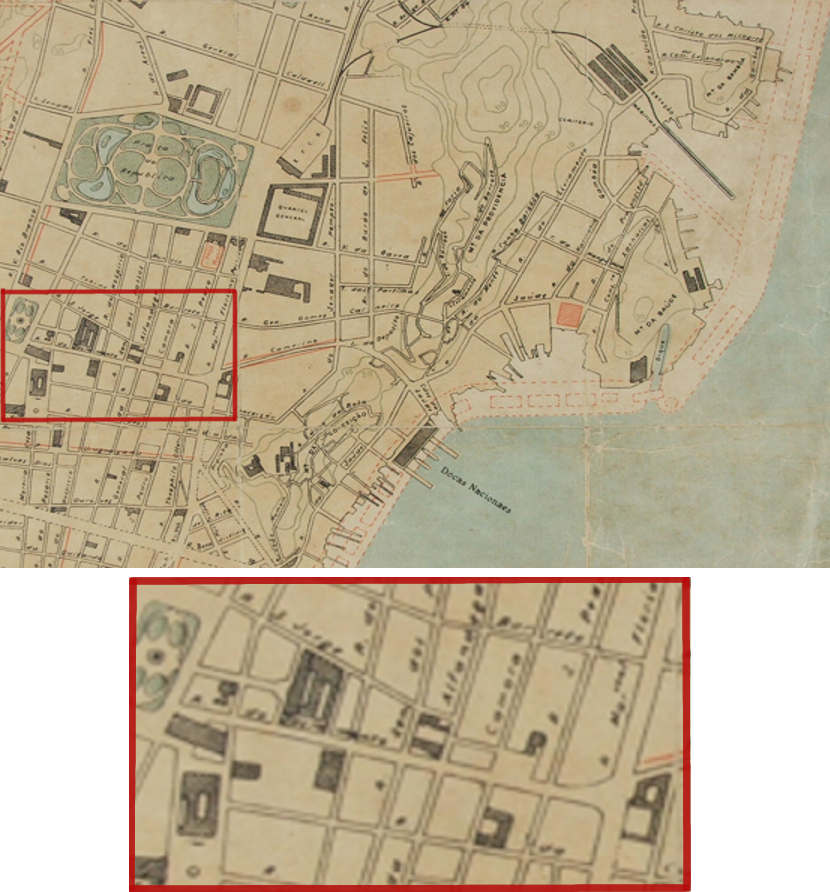

- Works on Sacramento Street

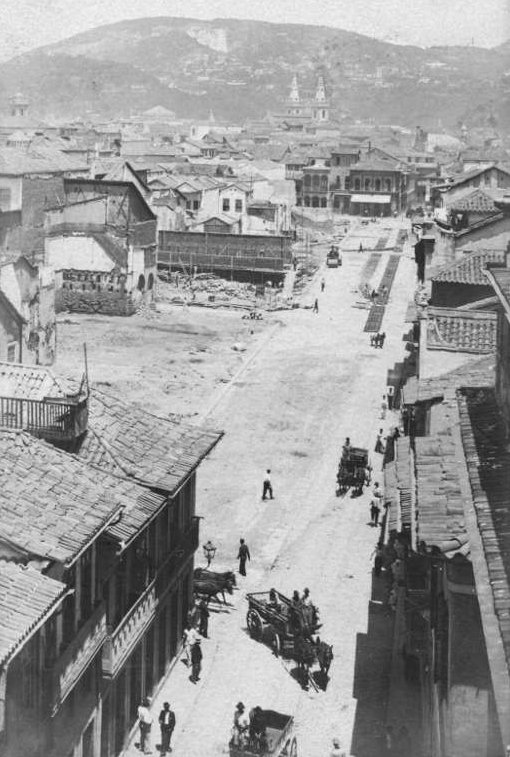

The extension of Sacramento Street would significantly improve air circulation and the movement of goods unloaded at the Dom Pedro II Railway Station and the Port of Rio de Janeiro, as well as pedestrian traffic. The street would connect to Camerino Street, which was also slated for widening and linkage to the new port (Figure 8).

To carry out the widening and extension of Sacramento Street, numerous buildings had to be demolished (Figures 9, 10, and 11), as detailed in the following public notice (Distrito Federal, 1903b, p. 259):

Public Notice from the Federal District Municipality, extension of Sacramento Street to Marechal Floriano Peixoto Street and Widening of Camerino Street to Saúde Quay. By order of the Mayor and for public awareness, the Municipality hereby announces that, to extend Sacramento Street to Marechal Floriano Peixoto Street and widen Camerino Street to Saúde Quay, it requires the acquisition of the following properties: Senhor dos Passos Street: Nos. 53, 70, 72, and 76; Alfândega Street: Nos. 211–217, 223, 216–218, 222, and 230; General Câmara Street: Nos. 211–217, 192, and 194; Largo de São Domingos: Nos. 8, 10, and 12; São Pedro Street: Nos. 187–191, 206, 210–214; Marechal Floriano Street: Nos. 91–95, 99, 101, and 66; Camerino Street: Nos. 3–13, 17–33, 47–61, 67–79, 83–89, 93, 97–101, 105–121, 127–131, 139, 145, 56–60, 64–70, 74, 76, 80, 104–124, 132–142, 148–166, and 174; Senador Pompeu Street: No. 80. Payment will be made in municipal bonds yielding 6% interest, adjusted for property taxes (décima), water penalty taxes (pena d’água), and insurance premiums. Property owners must submit proposals to this Directorate, accompanied by proof of ownership, a certificate of unencumbered title, and evidence of settled property and water taxes. 1st Sub-Directorate of the General Directorate of Works and Transportation, April 15, 1903 – Interim General Director, C.A. do Nascimento Silva

The Academy of Medicine argued that extending Sacramento Street would yield no aesthetic benefit, as it would abut one side of the Church of São Joaquim (Figure 9), overlooking that prior to the extension, the street frontally abutted buildings on Senhor dos Passos Street. The church in question was ultimately demolished.

Figure 8: Map of 1903. The red lines illustrate the city's construction works. Highlighted in yellow is Sacramento Street, with an enlarged view in the box below the map.

Source: General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro.

Figure 9: Church of São Joaquim before and during its demolition for the extension of Sacramento Street and the widening of Marechal Floriano and Camerino Streets (1903).

Source: Historical Archive of the Museum of the Republic.

Figure 10: Largo de São Domingos during the construction works on Sacramento Street (1903). With the opening of Avenida Presidente Vargas, the square disappeared.

Source: Historical Archive of the Museum of the Republic. (photograph by Augusto Malta)

Figure 11: Sacramento Street: Panoramic view towards Praça Tiradentes during the demolitions for its extension (1903).

Source: Historical Archive of the Museum of the Republic. (photograph by Augusto Malta)

Del Brenna (1985) reports that a newspaper from the time, titled O Commentário, wrote in its June 1903 edition:

The city of Rio de Janeiro is under construction. [...] Along Senhor dos Passos Street, Alfândega Street, General Câmara Street, and Largos São Domingos, extending through Camerino Street, an extraordinary wave of demolitions has unfolded. Rows of houses crumble under the blows of sledgehammers and mallets. This is the extension and widening of Sacramento Street — a project of construction that is rooted in the destruction of many shacks and the disappearance of narrow, suffocating alleys where pedestrians once slipped through. Crowds gather from morning until night to witness the spectacle of rooftops collapsing, walls crumbling, and doors and windows disintegrating; there seems to be an voluptuous pleasure in standing there, covered in the dust of suspended lime. The very air over the zone where the new street is being carved out appears to shimmer. These are the effects of a determined will — there has been no opposition to this improvement. Property owners, residents, shopkeepers, all complied and gradually abandoned the affected buildings. Within days, nearly all facades bore signs reading ‘relocated to...’ or ‘to be rebuilt as...’. Each person sought a new home, a new business. Countless carts move in and out constantly, carrying away the debris of the demolitions. This has been ongoing for more than thirty days, and yet there is still much to demolish, much to transport. [...] The city of Rio de Janeiro is under construction. The Federal District has found its man.

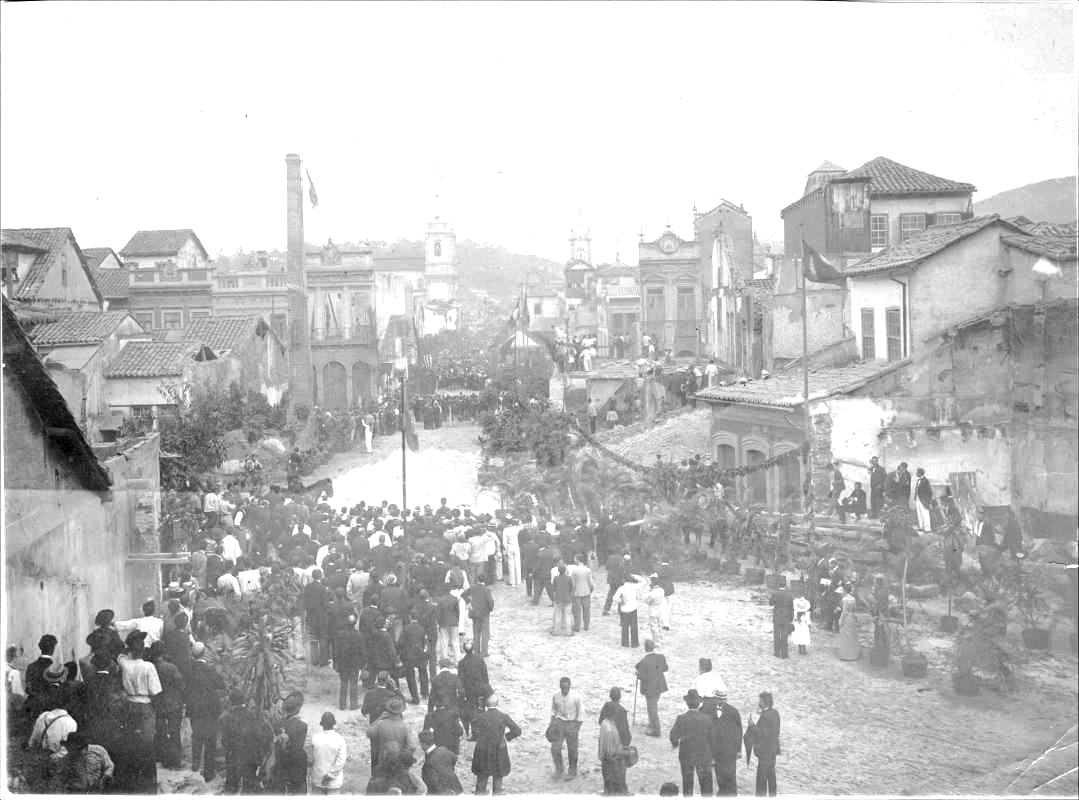

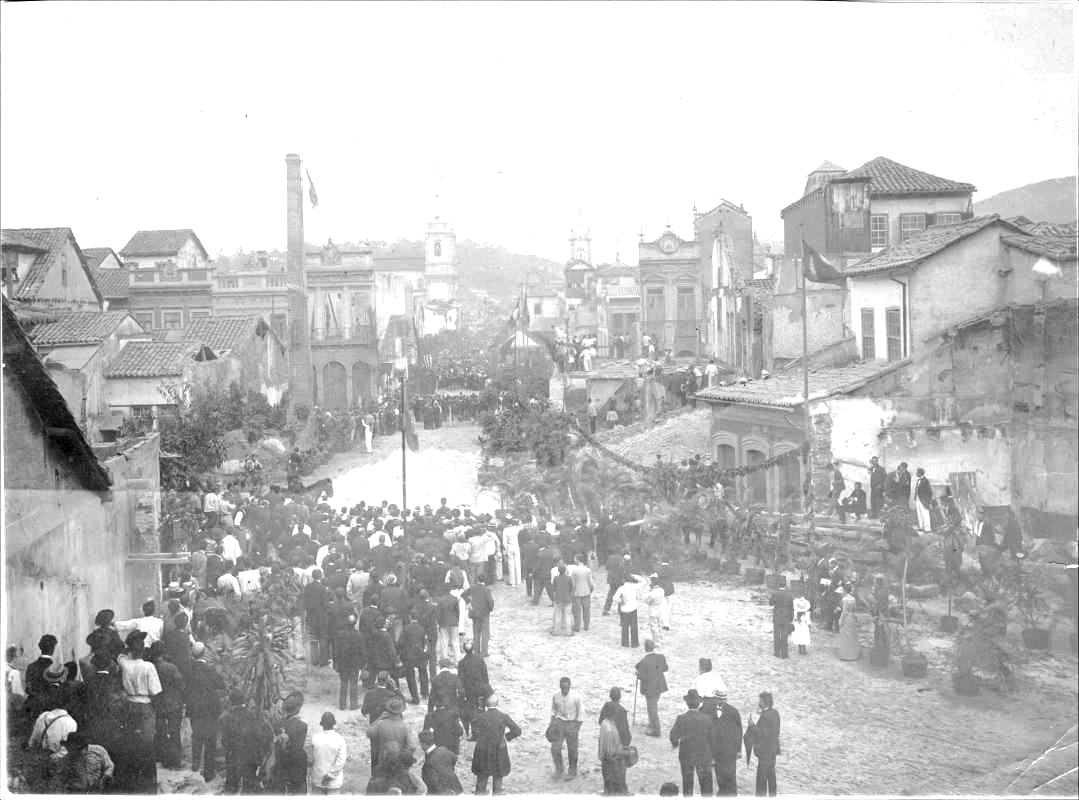

Amid both criticism and praise, the mayor remained steadfast in his vision, and on June 27, 1903, the extension of Sacramento Street (Figure 12) was inaugurated in the presence of President Rodrigues Alves and a crowd that enthusiastically chanted "Avenida Passos”.The widening and extension of Sacramento Street represented the first major urban project undertaken by Pereira Passos as Mayor of the Federal District.

Figure 12: General view of the inauguration of the construction works on Sacramento Street (1903).

Source: Historical Archive of the Museum of the Republic (photograph by Augusto Malta)

In addition to President Rodrigues Alves, who arrived in a Landau carriage alongside Pereira Passos as previously mentioned, attendees included Dr. Rodrigues Alves Filho (Private Secretary to the Presidency of the Republic); Colonel Souza Aguiar (Head of the Military Household); Dr. J. J. Seabra (Minister of the Interior); Dr. Lauro Müller (Minister of Transportation); Dr. Leopoldo Bulhões (Minister of Finance); Dr. Cardoso de Castro (Chief of Police); Colonel Souza Aguiar (Commander of the Fire Department); Dr. Moraes Rego (representing the Minister of War); Dr. Nascimento Silva; Dr. Heronymo Coelho; Dr. Luiz Durão; Dr. Alvarenga Fonseca; Dr. Paulino Werneck; Dr. Manoel M. del Castilho; members of the press; crowds of onlookers; and a music band performing the National Anthem. Flags and foliage garlands adorned the masts.

During the ceremony, President Rodrigues Alves and Mayor Pereira Passos cut the inaugural ribbon for the street extension (Figure 13), accompanied by fireworks, the National Anthem, and showers of rose petals. Thus began the celebrations marking the first major project of the Passos administration.

Figure 14:Sacramento Street and Largo de São Domingos after the construction works (1905).

Source: General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro (postcard photograph, author unknown).

Table 5 shows that the preliminary budget for the extension of Sacramento Street was as follows (Distrito Federal, 1903c):

Table 5: Expropriation Budget

Project | Expropriations calculated at 20x the rental value | Paving, landscaping, and other expenses |

Widening of Sacramento Street | 3.643:828$000 (approximately R$ 448,190,844.00, according to Diniz, 2022) | 128:004$000 (approximately R$ 15,744,492.00, according to Diniz, 2022) |

Source: Distrito Federal (1903c)

It can be inferred that the lots resulting from expropriations were highly sought after in the burgeoning real estate market of the Federal District, based on applicant records documented in codices from the General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro (Table 6). Information on Lots 1, 2, and 16 was sourced from Codex 22-4-18, folios 21–24, 33–37, and 42–45; Lot 40 was researched in Codex 23-2-10, folios 103–108; and Lots 12 and 14 were identified through applicants listed in Codex 23-2-9, folios 150–155. These buildings, of varied typologies, reflect robust real estate activity on the newly reformed and extended street, attracting interest from capitalists and entrepreneurs of the era.

Regarding this real estate activity, the 1907 Census identifies two industries established on Sacramento Street (now Passos Avenue), as shown in Table 7. This suggests that industrial and service-sector dynamics emerged shortly after the street’s completion, reinforcing its economic revitalization.

Table 6: Application Processes for New Lots

Lot No. | Building No. | Applicant | Activity | Date |

2 | 51 | José Joaquim Lopes | 1st floor: a warehouse. 2nd floor: 2 living rooms, 5 bedrooms, pantry, kitchen, bathroom, and courtyard. | 30/01/1904 |

16 | 44 | Antônio Gomes Vieira de Castro | 1st floor: warehouse, bathroom, and courtyard. 2nd floor: 2 living rooms, 2 bedrooms, kitchen, courtyard, and bathroom. | 04/04/1904 |

1 | 35 | Associação Typographica Fluminense | No blueprint included in the application. | 13/04/1904 |

40 | 68 | Abílio Antonio Martins Vianna | No blueprint included in the application. | 10/09/1904 |

12 &14 | 40 & 42 | Dr. Antônio de Pádua Assis Rezende | No blueprint included in the application. | 04/04/1904 |

Source: General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro.

Table 7: Number of Tenements, Rooms, Inns, Location, and Population in the Parish of Sacramento

Activity | Location | Owner | Capital | Power | Production Value | Number of Workers

|

Beer | Av. Passos, 26 | Rodrigues Figueiredo | 20:000$ | Manual | 140:000$ | 15 |

Footwear | Av. Passos, 66 | Antonio da Silva | 75:000$ | 3hp | 242:000$ | 25 |

Source: Lobo (1978, p. 577-579)

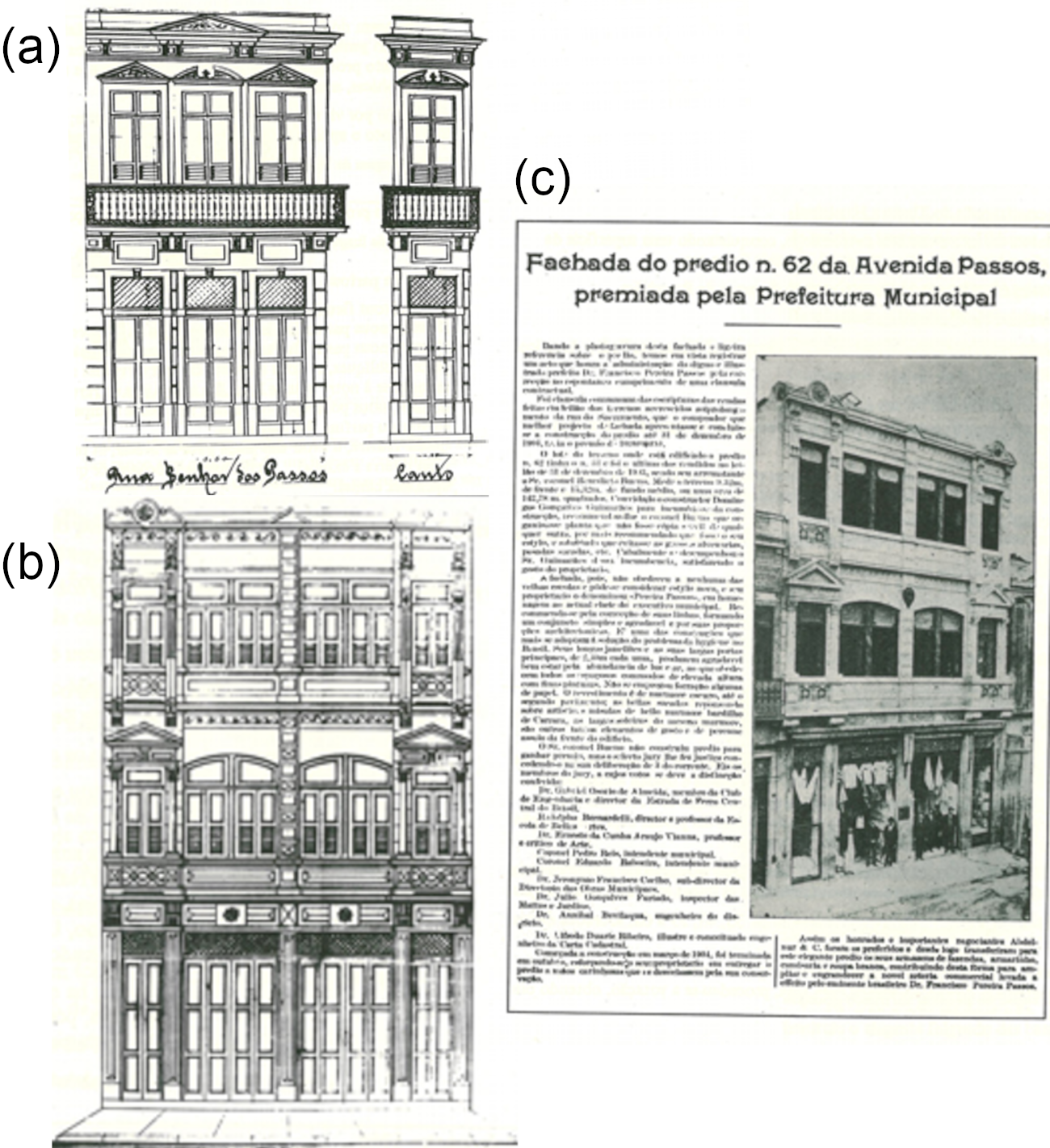

It can also be inferred that the new lots, as well as pre-existing ones, were subject not only to extensive construction activity but also to architecture reflecting the era’s tastes—featuring diverse eclectic-style designs. Figure 15 showcases two such projects, including a prize-winning building at number 62, awarded by the Municipal Government in 1905.

The extension of Sacramento Street thus became vital for circulation in Rio de Janeiro. This is explicitly outlined in Municipal Decree 459 of December 19, 1903, which modified Camerino Street’s layout, extending it by 432 meters and widening it to 17 meters. This adjustment connected Camerino Street to Praça Tiradentes via Sacramento Street and Marechal Floriano Street, facilitating rapid access to the port area (Figure 16).

Figure 15: Facade designs for the new Sacramento Street: (a) corner with Senhor dos Passos Street and (b) number 62 (lot 34). Image (c) is a newspaper report from O Malho, dated January 14, 1905, about the award won by project (b).

Source: General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro.

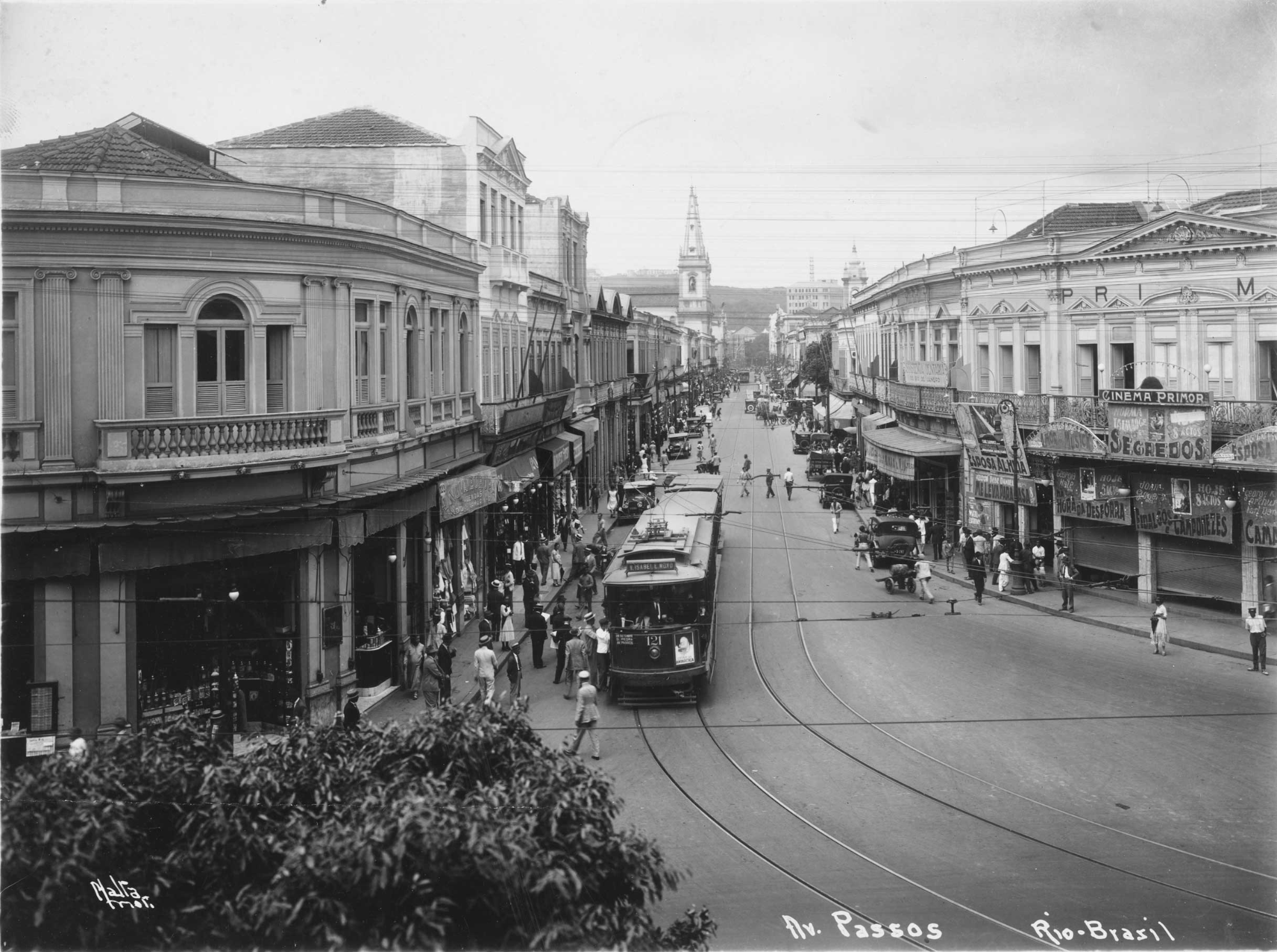

Finally, on August 29, 1910, through Executive Decree No. 798, the former Sacramento Street was officially renamed Passos Avenue. The idea came from Mayor Serzedelo Correia, honoring Pereira Passos on his birthday (Clube de Engenharia, 1936). By then, Sacramento Street—now Passos Avenue—had become a revitalized central Rio address, connected by new thoroughfares designed to enhance the flow of people and goods. This urban experiment laid the groundwork for larger challenges undertaken in subsequent years.

Figure 16: Map of 1905. The red lines illustrate the city's construction works. This map already shows the extension of Sacramento Street, which would connect to Camerino Street, and from there, to the New Port of Rio de Janeiro.

Source: General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro.

5.6The Continuation of Urban Reform and the Evolution of Sacramento Street

Despite the complexity of the broader context of the Passos Reform and the evolution of Passos Avenue to the present day, it is essential to highlight key milestones to contextualize the significance of the works on Sacramento Street.

Though relatively modest in scale, these projects marked the inception of what we now call the Passos Reform. Consequently, they established a recurring pattern of (typically compensated) expropriations, demolition of buildings and even hills, and restructuring into wide avenues suited to emerging motorized vehicles: trams, automobiles, and buses. This led to the complete transformation of central Rio into the urban landscape we recognize today, as illustrated in Figure 17. Demolitions, leveling, and landfills created experimental spaces where the city could be rebuilt according to fashionable architectural standards (Silva, 2019). Initially, the eclectic style dominated Passos Avenue and the new Central Avenue (now Rio Branco Avenue). Later, modern styles, in their numerous variations, emerged along Presidente Vargas Avenue and through demolitions driven by the real estate market over the 20th century.

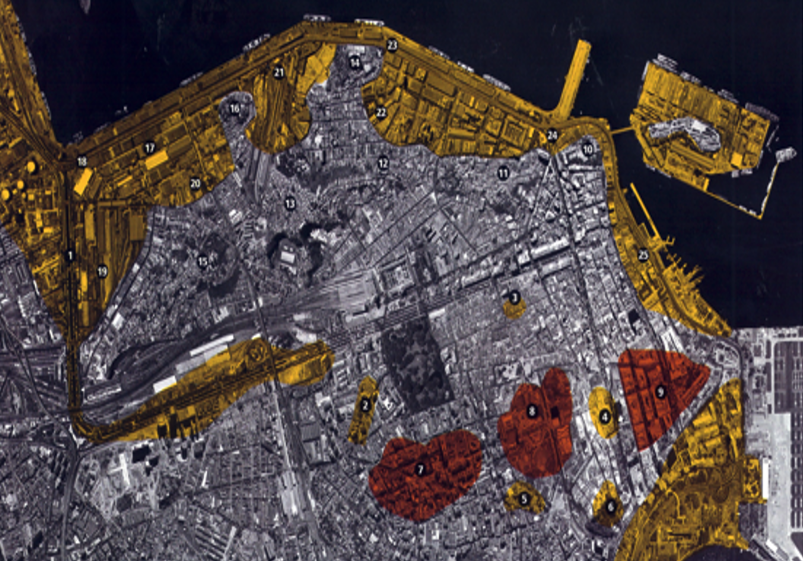

Figure 17: Urban transformations in downtown Rio de Janeiro. Yellow indicates landfill areas, while red marks hill removal areas.

1. Gamboa Grande (Braço do Mar); 2. Lagoa da Sentinela; 3. Lagoa da Pavuna (in the Parish of Sacramento); 4. Lagoa de Santo Antônio; 5. Lago do Desterro; 6. Lagoa do Boqueirão; 7. Morro do Senado; 8. Morro de Santo Antônio; 9. Morro do Castelo; 10. Morro de São Bento; 11. Morro da Conceição; 12. Morro do Livramento; 13. Morro da Providência; 14. Morro da Saúde; 15. Morro da Gamboa; 16. Morro do Pinto; 17. Ilha das Moças; 18. Ilha dos Cães; 19. Praia Formosa; 20. Saco do Alferes; 21. Saco da Gamboa; 22. Valongo; 23. Praia da Saúde; 24. Prainha; e 25. Praia dos Marinheiros.

Source: Pereira Passos Municipal Institute of Urban Planning.

These processes of removal and reconstruction were often exclusionary, displacing the low-income population traditionally residing in the city center to distant suburbs or, lacking better options, to favelas. The new, modern, and stylish avenues could no longer accommodate tenements (cortiços) or impoverished residents. The poor now traversed these spaces as workers, not as residents.

Gradually, the city center’s role shifted. Small factories vanished amid Rio de Janeiro’s deindustrialization, replaced by corporate buildings and commercial enterprises. Throughout the 20th century, the center also lost its residential population—a trend that persists today, though recent public policies promoting housing in the area suggest potential reversal.

Curiously, Passos Avenue retained much of its original urban fabric. It stands as a rare exception among major thoroughfares opened or reformed during this era, with many Pereira Passos-era buildings still intact. Mid-20th-century photographs (Figure 18) reveal minimal changes to its architectural composition. Even today (Figure 19), rooftops reminiscent of early 20th-century buildings remain identifiable (though the preservation of their facades varies). New developments, such as those along Presidente Vargas Avenue or subway construction, have impacted the area less severely than other parts of downtown.

Figure 18: Avenida Passos in the mid-20th century.

Source: Historical Archive of the Museum of the Republic (photograph by Augusto Malta).

Figure 19: Avenida Passos highlighted in a 2024 orthophoto. The interruption in its layout due to the opening of Avenida Presidente Vargas is noticeable. It is also evident that many of the buildings on both sides of the street have been preserved in some form, as indicated by their roof styles and property dimensions. In this sense, the landscape of Avenida Passos has remained much more stable than that of Avenida Rio Branco.

Source: Pereira Passos Municipal Institute of Urban Planning.

Situated within a bustling commercial hub, Passos Avenue became the axis of the SAARA district (Sociedade dos Amigos das Adjacências da Rua da Alfândega), which evolved into a zone specializing in fabrics, clothing, home goods, and festive items. While low-income residents could no longer live on Passos Avenue, they could still navigate it—not as workers, but as consumers.

This prompts a reflection on history as a lesson for future generations. Urban reforms are—and will remain—an inherent part of cities’ evolution. Cities are organic, living entities that cannot be frozen in time. However, urban reforms that neglect social justice (FAINSTEIN, 2007, p. 13) risk failing to achieve their intended outcomes.

Azevedo (2003) notes that Pereira Passos himself lamented, years later, the emptiness of the avenues he designed:

Pereira Passos intended to make the city center a space for ‘civilized’ interaction—a place that would attract residents from across Rio to learn urban ethics and the civility meant to permeate the entire city. [...] Disheartened, Passos expressed disappointment at the sparse use of central Rio’s grand avenues by its people. His desire for residents to engage with the reformed area is evident in his lament over the underuse of public spaces: ‘This is what we lack here.’ [...] As a member of Rio’s elite, Passos was alarmed by the city’s rapid population growth and its potential for social disruption. His conservative approach sought to spiritually ‘elevate’ the working class and improve their living conditions to avert major social conflicts. While undeniably conservative, Passos undeniably envisioned a project of urban integration.

Yet, it is impossible to ignore that Rio’s housing deficit worsened under the Passos Reform, as social housing was absent from the hygienist agenda and urban redesign proposals (Macedo, 2022, pp. 40-42).

Figure 20: Popular commerce at the corner of Avenida Passos and Buenos Aires Street.

Source: Wikimapia (photograph by Denis Gahyva).

In this sense, if there are enduring elements to be identified in Sacramento Street, it is because — however limited — the street remained a space of democratic circulation (Figure 20). This persistence occurred despite the very features that disgusted the engineer-mayor: the “uncivilized,” unrefined popular commerce, with shops spilling their counters onto the street, blaring music, and crowds hauling shopping bags. It may not appeal to refined sensibilities. Yet, this is life in the urban fabric.

Conclusion

The Urban Reform carried out in Rio de Janeiro between 1902 and 1906, at both federal and municipal levels, profoundly transformed the city’s urban landscape. New roads integrated distant areas, and social customs began to shift, largely inspired by Parisian urban models. During this period, a new consumption pattern emerged, driven by illustrated magazines and later by the phonographic industry and cinema.

In November 1906, President Rodrigues Alves handed over power to Afonso Pena. By then, Rio de Janeiro had been remodeled and sanitized, rebranded as the “Marvelous City.”

The era of Pereira Passos’s reforms marked an urban revolution, where new forms of social organization redefined the city’s functions. This required the elimination of old structures, representing a forceful state intervention. However, with the destruction of many dwellings, the city’s hills began to be occupied by displaced populations — particularly those unable to relocate to suburbs, as the city center still concentrated major workplaces amid growing industrialization.

It would be inaccurate to claim Mayor Passos ignored the downtown residents. On the contrary, he incentivized the construction of worker housing (vilas operárias), as seen in the case of Arthur Sauer and his correspondence with Américo Rangel. Yet this period was also marked by intense conflict, such as the Vaccine Revolt (1904), which resulted in numerous casualties — all in the name of order and modernity.

The extension of Sacramento Street, renamed Passos Avenue, became crucial for urban mobility. New buildings arose along this corridor, many still standing today, now housing commercial enterprises rather than residences. With the demolition of Morro de Santo Antônio in the 1950s, the avenue gained further prominence, forming a major traffic axis connecting Rodrigues Alves Avenue (near the Port of Rio) to Marechal Floriano Avenue, Presidente Vargas Avenue, Praça Tiradentes, and extending to Lapa and the South Zone. The streets intersecting Passos Avenue now form a bustling hub for wholesale and retail commerce.

Later, in the name of the same modernity championed in 1903, many buildings from the Urban Reform era were gradually demolished to make way for skyscrapers, as seen today along Rio Branco Avenue (formerly Central Avenue).

Nevertheless, infrastructure and housing challenges persist in Rio de Janeiro. Studying the reforms to Sacramento Street serves not only as a prelude to analyzing 20th-century urban transformations (and the Passos Reform as a whole) but also as a self-critical reflection on the unintended consequences of urban renewal. As Rio envisions future transformations, it is vital to learn from past successes and failures—to pursue reforms that balance modernity with social and spatial justice.

References

ABREU, Maurício de Almeida. Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro. 4. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Pereira Passos, 2006.

ABREU, Maurício de Almeida. Da habitação ao hábitat: a questão da habitação popular no Rio de Janeiro e sua evolução. In: Revista Rio de Janeiro, v. 1, n. 1, p. 87-105, set./dez. 1985. Niterói: EDUFF.

ARQUIVO GERAL DA CIDADE DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Códice 80-5-11. Rio de Janeiro: Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, 1875-1876.

ARQUIVO GERAL DA CIDADE DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Códice 44-2-8. Rio de Janeiro: Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, 1882-1883.

ARQUIVO GERAL DA CIDADE DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Códice 53-3-7. Rio de Janeiro: Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, [s.d.].

ATHAYDE, Raymundo Austregésilo. Pereira Passos, o reformador do Rio de Janeiro: biografia e história. Rio de Janeiro: A Noite, [s.d.].

AZEVEDO, André Nunes de. A reforma Pereira Passos: uma tentativa de integração urbana. Revista Rio de Janeiro, n. 10, maio-ago. 2003.

BACKEUSER, Everardo. Habitações populares: relatório apresentado ao Exmo. Sr. Dr. J.J. Seabra, Ministro da Justiça e Negócios Interiores. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, 1906. 105 p.

BENCHIMOL, Jaime Larry. Pereira Passos – um Haussmann tropical: as transformações urbanas na cidade do Rio de Janeiro no início do século XX. 1982. Dissertação (Mestrado em Planejamento Urbano e Regional) – COPPE, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 1982. v. 2.

CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS. Documentos parlamentares – 9: mensagens presidenciais. 1890-1910. Centro de Documentação e Informação. Brasília, 1978.

CARVALHO, Bulhões. Anuário de estatística demográfico-sanitária do Distrito Federal e algumas capitais. Ano I. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, 1897.

CARVALHO, Lia de Aquino. Contribuição ao estudo das habitações populares: Rio de Janeiro: 1866-1906. Rio de Janeiro: Departamento de Cultura, Departamento Geral de Documentação e Informação Cultural, Divisão de Editoração, 1985.

CARVALHO, Carlos Delgado de. História da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Secretaria Municipal de Cultura, Departamento Geral de Documentação e Informação Cultural, 1988.

CAVALCANTI, João Curvelo. Nova numeração dos prédios da cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Gazeta de Notícias, 1878.

CLUBE DE ENGENHARIA. Revista do Clube de Engenharia. Ano II, n. 23, ago. 1936.

DEL BRENNA, Giovanna Rosso. O Rio de Janeiro de Pereira Passos: uma cidade em questão II. Rio de Janeiro: Index, 1985.

DINIZ, Bruno. Conversão hipotética dos réis para o real. 2022. Disponível em: https://www.diniznumismatica.com/2015/11/conversao-hipotetica-dos-reis-para-o.html. Acesso em: 15 fev. 2025.

DISTRITO FEDERAL. Boletim da Intendência Municipal publicado pela Diretoria Geral de Polícia Administrativa, Arquivo e Estatística. Abril a junho de 1903. Ano XLI. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia da Gazeta de Notícias, 1903a.

DISTRITO FEDERAL. Decreto nº 391, de 10 de fevereiro de 1903. Rio de Janeiro, 10 fev. 1903b.

DISTRITO FEDERAL. Mensagem do Prefeito do Distrito Federal lida na sessão do Conselho Municipal de 01.07.1903. Rio de Janeiro: Tipografia Gazeta de Notícias, 1903c.

DISTRITO FEDERAL. Consolidação das leis e posturas municipais. Rio de Janeiro, 1905.

FAINSTEIN, Susan S. Urban planning and social justice. In: The Routledge handbook of planning theory. 1st ed. London: Routledge, 2017. eBook ISBN 9781315696072.

GERSON, Brasil. História das ruas do Rio: e da sua liderança na história política do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Lacerda Editores, 2000. p. 357.

IBITURUNA, Barão de. Projeto de alguns melhoramentos para o saneamento do Rio de Janeiro apresentado ao Governo Imperial pela Inspetoria Geral de Higiene. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia de Pereira Braga e C., 1886.

IPLANRIO. Guia das igrejas históricas da cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: IPLANRIO, 1997.

LAMARÃO, Sérgio Tadeu de Niemeyer. Dos trapiches ao porto: um estudo sobre a área portuária do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Secretaria Municipal de Cultura, Turismo e Esportes, Departamento Geral de Documentação e Informação Cultural, Divisão de Editoração, 1991.

LEEDS, Anthony; LEEDS, Elizabeth. A Sociedade do Brasil Urbano. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1978.

LINHARES, Maria Yedda Leite. História do abastecimento: uma problemática em questão (1530-1918). Brasília: BINAGRI, 1979. 150 p.

LOBO, Eulália Maria Lahmeyer. História do Rio de Janeiro: do capital comercial ao capital financeiro. Rio de Janeiro: IBMEC, 1978. v. 2.

MACEDO, Ana Clara Pereira. A reforma Pereira Passos como mito de origem de uma cidade partida. 2022. 68 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Sociologia) – Instituto de Estudos Sociais e Políticos, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2022.

MATHIAS, Herculano Gomes. Viagem pitoresca ao velho e ao novo Rio. Rio de Janeiro: Secretaria de Turismo do Estado da Guanabara, Superintendência do IV Centenário da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, Gráfica Olímpica Editora Luiz Franco, 1965. 217 p.

MAURÍCIO, Augusto. Igrejas históricas do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Kosmos Editora/SEEC/RJ, 1977.

PECHMAN, Robert Moses. De civilidades e incivilidades. In: Revista Rio de Janeiro, v. 1, n. 1, set./dez. Niterói: EDUFF, 1985. p. 134.

PINHEIRO, Victor de Oliveira. O Rio de Janeiro e seus prefeitos: evolução urbanística da cidade. Rio de Janeiro: Prefeitura da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, 1977.

PIMENTEL, Antonio Martins de Azevedo. Subsídios para o estudo de higiene no Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia e Lyth de Carlos Gaspar da Silva, 1890.

ROCHA, Oswaldo Porto. A era das demolições: cidade do Rio de Janeiro: 1870-1920. Rio de Janeiro: Departamento de Cultura, Departamento Geral de Documentação e Informação Cultural, Divisão de Editoração, 1985.

SILVA, Mayara Grazielle Consentino Ferreira da. Algumas considerações sobre a reforma urbana Pereira Passos. Urbe: Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana, v. 11, 2019. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-3369.011.e20180179. Acesso em: 20 jan. 2025.

SEARA, Berenice. Guia de roteiros do Rio Antigo. Rio de Janeiro: Infoglobo Comunicações Ltda., 2004.

SEVCENKO, Nicolau. O prelúdio republicano, astúcias da ordem e ilusões do progresso. In: História da Vida Privada no Brasil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1998. v. 3.

SODRÉ, Azevedo. A administração do Dr. Francisco Pereira Passos no Distrito Federal. Rio de Janeiro: Tipografia d’O Economista Brasileiro, 1906.

VAZ, Lílian Fessler. Contribuição ao estudo da produção e transformação do espaço da habitação popular: as habitações coletivas no Rio antigo. 1985. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro.

About the Author

Nelson de Paula Pereira is a Master's candidate in Political Sociology at the University Research Institute of Rio de Janeiro (IUPERJ). He holds a Bachelor's degree and full teaching certification in History, a teaching degree in Pedagogy, and a postgraduate specialization in Brazilian History. For fourteen years, he served as a historian for the Presbyterian Church of Rio de Janeiro, coordinating the Documentation Center (CENDOC) and directing the Museum of the Presbyterian Church of Rio de Janeiro. Currently, he works as a History and IB (International Baccalaureate) Brazilian Social Studies teacher, as well as a historian and curator of the collection for the Presbytery of Rio de Janeiro. His expertise lies in History, with a focus on the History of Rio de Janeiro and Christian History, as well as Museums, Documentation Centers, and Archives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.P.P.; methodology, N.P.P.; validation, N.P.P.; formal analysis, N.P.P.; investigation, N.P.P.; resources, N.P.P.; data curation, N.P.P.; writing—original draft preparation, N.P.P.; writing—review and editing, N.P.P.; visualization, N.P.P.; supervision, N.P.P.; project administration, N.P.P.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the contributions of the technical staff at the Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro (General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro) and the Biblioteca Nacional (National Library) for providing access to primary and secondary documentary sources.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

About Coleção Estudos Cariocas

Coleção Estudos Cariocas (ISSN 1984-7203) is a publication dedicated to studies and research on the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, affiliated with the Pereira Passos Institute (IPP) of the Rio de Janeiro City Hall.

Its objective is to disseminate technical and scientific production on topics related to the city of Rio de Janeiro, as well as its metropolitan connections and its role in regional, national, and international contexts. The collection is open to all researchers (whether municipal employees or not) and covers a wide range of fields — provided they partially or fully address the spatial scope of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Articles must also align with the Institute’s objectives, which are:

1. to promote and coordinate public intervention in the city’s urban space;

2. to provide and integrate the activities of the city’s geographic, cartographic, monographic, and statistical information systems;

3. to support the establishment of basic guidelines for the city’s socioeconomic development.

Special emphasis will be given to the articulation of the articles with the city's economic development proposal. Thus, it is expected that the multidisciplinary articles submitted to the journal will address the urban development needs of Rio de Janeiro.