Volume 13 Issue 1 *Corresponding author therezacarvalho@id.uff.br Submitted 6 feb 2025 Accepted 9 apr 2025 Published 16 apr 2025 Citation CARVALHO, T. C. C.; STROZENBERG, A.; VELASCO, F. C.. Rio de Janeiro: beach, kiosks, bicycles, humour and Instagram. Coleção Estudos Cariocas, v. 13, n. 1, 2025.

DOI:10.71256/19847203.13.1.134.2025 The article was originally submitted in PORTUGUESE. Translations into other languages were reviewed and validated by the authors and the editorial team. Nevertheless, for the most accurate representation of the subject matter, readers are encouraged to consult the article in its original language.

| Rio de Janeiro: beach, kiosks, bicycles, humour and Instagram Rio de Janeiro: praia, quiosques, bicicleta, humor e Instagram Río de Janeiro: playa, quioscos, bicicletas, humor e Instagram Thereza Christina Couto Carvalho1*, Alberto Strozenberg2

and Fábio Carneiro Velasco3 1Full Professor PPGAU/UFF, Niterói, RJ, ORCID 0000-0002-5980-1430, therezacarvalho@id.uff.br 2Statistical Engineer, Researcher at RCORT/PPGAU/UFF, Niterói, RJ,

ORCID 0009-0000-6470-913X, albertostrozenberg@gmail.com 3Architect and Urbanist, Researcher at RCORT/PPGAU/EAU/UFF, Niterói, RJ,

ORCID 0009-0008-7174-410X, fcarneirovelasco@gmail.com

AbstractThis article evaluates the performance of the urban project implemented on the beach coast of Rio de Janeiro called Rio Orla Project. It deals with sustainable mobility, bike lanes, the evolutionary morphology that distinguishes it and its repercussions in the press - from the perspective of cartoonists at the time of its realization - and its digital developments today, on Instagram. It covers three seashores: from Leme to Copacabana, from Arpoador to Leblon and St. Conrado. It stands out, from its inauguration up to today, by supporting various forms of social appropriation and their cumulative transitory transformations. Keywords: city, mobility, waterfront, Rio de Janeiro, urban morphology, appropriations. ResumoEste artigo avalia o desempenho do projeto urbanístico implantado na costa praiana do Rio de Janeiro denominado Projeto Rio Orla. Trata da mobilidade sustentável, das ciclovias, da morfologia evolutiva que o distingue e das repercussões que alcança na imprensa - sob a ótica do humor dos chargistas à época da sua realização - e seus desdobramentos digitais na atualidade, no Instagram. Abrange três trechos: do Leme a Copacabana, do Arpoador ao Leblon e São Conrado. Destaca-se a potência revelada do projeto ao longo da sua duração, apoiando variadas formas de apropriação social e respectivas transformações transitórias cumulativas. Palavras-chave: cidade, mobilidade, orla, Rio de Janeiro, morfologia urbana, apropriações. ResumenEste artículo evalúa el desempeño del proyecto urbano implementado en la costa de playa de Río de Janeiro llamado Proyecto Río Orla. Se ocupa de la movilidad sostenible, los carriles para bicicletas, la morfología evolutiva que la distingue y las repercusiones que alcanza en la prensa, desde la perspectiva de los dibujantes en el momento de su realización, y sus desarrollos digitales hoy, en Instagram. Cubre tres extractos: desde el Leme hasta Copacabana, de Arpoador a Leblón y San Conrado. Destaca el poder revelado del proyecto, a lo largo de su duración, respaldando varias formas de apropiación social y sus transformaciones transitivas cumulativas. Palabras clave: ciudad, movilidad, frente marítimo, Río de Janeiro, morfología urbana, apropiaciones |

Introduction

The occupation of the waterfront has a relatively recent history, beginning in the late 19th century. Since then, it has been promoted as an object of desire for “modern” consumption by specific, wealthy social groups, driven by different economic factions that aimed to extend their territorial monopoly over transportation, electric streetcars. Modern in the sense of customs imported from the European bourgeoisie, the practice of sunbathing by the seaside was documented by various painters as early as the mid-19th century. Socio-spatial stratification was adopted as a purpose for urban configuration in the occupation of the beachfront, leading to long-term consequences.

The state, in defining the city’s form, concentrated public resources on beautifying the Zona Sul, privileging the dominant classes and encouraging consumption in bourgeois neighborhoods. Its participation remained indifferent to the industries multiplying across the city, which expanded beyond the central district, urbanizing new areas with their own resources, creating jobs, attracting labor, and simultaneously occupying suburbs and generating favelas. Abreu (1987, p. 72) emphasizes that “as financiers of both consumption and production, national and foreign banks benefited from the actions of public and private sectors, increasing their influence over vast areas of the economy.” Thus, the process of socio-spatial stratification in the city became entrenched and accelerated. Seemingly, little has changed.

The promotion of the therapeutic effects of sea bathing, associated with luxury consumption and reinforced by the recurrent attendance of aristocrats, amplified the appeal of these resorts and their reproduction as reference models for other parts of the world. This reached Rio de Janeiro as a “beachfront-civilizing project” (O’Donnell, 2013) during the administration of Mayor Pereira Passos in 1903. The call to occupy beaches with “elegance” gained traction starting in the 1920s, with real estate repercussions in the 1940s, thereafter linking the neighborhood’s image to Rio’s new elite.

The Rio Orla Project, launched in 1992 under Mayor Marcello Alencar, proposed the valorization of public space, the effects of which resonate to this day. This article addresses the ‘genetic capital’[1] accumulated along Rio’s waterfront since then, under the influence of this project and its transformations, as well as individual appropriations by each of us, from 1991 to 2024.

Analytical Perspective

The research underpinning this article began during the postdoctoral work of one of its three authors and addressed the role of public space in articulating centralities and configuring place. This configuration, understood as an incremental process, is never complete, and its incompleteness is a key part of its allure.

A decade after its inception, the postdoctoral research found synergy with the PLACE (Production of Place through Evolutionary Community Action) project, led by the Laboratory of Incremental Urbanism Generated by Architecture and Reuse and based at the Faculty of Architecture, University of Porto, Portugal. The Portuguese collaborators’ perspective prioritizes co-production with society and the joint design of cumulative solutions and material reuse. It thus involves active participation in community-led redesign. Our research path explores other possibilities of appropriation and unfolding, as detailed below.

The investigative procedure adopted in this research seeks to recognize the processes of urban configuration in everyday life. It starts by identifying interfaces between legacies and permanences, disruptive design interventions, urban planning, and the social, economic, and cultural practices observed in selected areas, all supported by connectivity and mobility.

In this analytical perspective, the interweaving of intervention scales, urban planning, design, and spontaneous configuration, arising from the transient appropriations that manifest in the daily lives of residents and visitors, takes center stage. Likewise, the interfaces that these interventions create in the territory, which sparked antagonistic popular reactions at the time of their construction, and were appropriated and disseminated differently today via Instagram, are highlighted.

Capturing the everyday landscape serves as a critical lens for reading the city as an artifact (Rossi, 2016), where the scale of urban experience reveals mechanisms of its construction by multiple agents. As a contested space, the city’s notion of polis is continuously revisited through its representations, discourses, and meanings. These platforms of urban social life, inherently collective, are not merely confined to materiality, as their boundaries of meaning now intersect with virtual gazes, such as those on social media. The virtual experience of cities may signal an ongoing development of new interpretive vectors for these spaces.

The contemporary informational context increasingly reinforces the understanding of networks as public space, attributing to them the emergence of “new spaces of interaction, visibility, and legitimization” (Pereira, 2018, p. 19). The internet has proven capable of projecting its possibilities for critique, behavior, and protest onto the friction of offline urban reality. Online debates about territorialities increasingly highlight the relevance between local-scale territory and its virtual value chains, suggesting that urban fragments might compose the links of a cybernetic hypertext: the landscape as a component of a digital hyperlink. In this condition, we would witness a new form of full-time apprehension, as daily life is transiently renegotiated between urban existence and social media.

The ongoing research adopts the concept of evolutionary morphology (Conzen, 1967) to express the incompleteness of urban form, always under construction. Attractive singularities, in six qualitative dimensions that distinguish the dynamic sedimentation process in the studied neighborhoods, fuel the permanence or shifts in routes and pathways (Carvalho, 2019). These dimensions are: the environmental dimension, defined by the coastline and framing hills; the economic dimension, shaped through collaboration with the real estate market; the social dimension of reception and rejection these areas provoke; the cultural dimension, which distinctively marks the imagination of residents/observers; the rules of production and consumption, which sought to limit uses through evolving conceptions of excess; and all underpinned by connectivity and mobility enabled by diverse transportation modes.

The interweaving of these dimensions emerges, in this study, in the form of distinct spatial patterns of dynamic sedimentation, in sequential or simultaneous phases, encompassing the uniqueness of the offering that attracts (attractive force), the demand and the enjoyment of this offering that gathers people along that route (aggregating), and the appreciating consolidation of this ensemble over time. These dimensions remain active in the current urban dynamics of the waterfront, despite apps like iFood, as they are territorially anchored by environmental attributes – beach, sea, and sun exposure.

Under these conditions, these dynamic sedimentation patterns support and explain the location of new transient commercial activities along selected stretches. This research investigates how different transient urban fabrics, emerging along the promenade, interact with consolidated routes of collective transportation, pedestrian pathways, and cycling lanes. It seeks to unravel how these circuits are interrupted by new objects and pathways inserted into daily life due to novel uses. It recognizes the episodic repercussions of major events that have claimed space on the beach, whose singularities and allure attract presence and duly shared Instagram documentation of lived prestige, even if temporarily borrowed. Disseminated on social media in “real time,” which “reduces to the tip of the present” (Han, 2021, p. 15), these images actively shape collective imagination.

Online 'facts' point to challenges in reading the city based on the ideas of internet users, namely, among other things, its instantaneity and self-centered discourse. Thus, the production of images on Instagram allows for visualizing the way the user experiences the landscape inseparably from how they would like to be seen. In this system, it is also worth highlighting how the algorithms of these technology companies work to amplify or notthe content treated as relevant. Therefore, based on these manifestations, the reading of everyday life presents tensions between individuality and collectivity, frequently reinforced or reinvented.

Squares, walkways, routes, edges, and connecting roadways, whether consolidated or transient, still maintain reciprocal relationships of intercomplementarity in their form and integration into the urban fabric. The location of these elements in the city, materializing intersections between public and private, movement and place, built and open space, architecture and planning, symbolic and utilitarian, now demands simultaneous attention to people, the physical environment, and their myriad virtual relationships mediated by social networks.

- Instagram

Instagram, initially created for photo sharing, now encompasses a variety of multimedia creation, sharing, and interaction possibilities. The company is highly recognized for the commercial and advertising use of the network, given its capacity to deliver content with a wide reach. The social network is renowned for its popularity and instantaneity, intertwining the daily lives of registered users with their corresponding media production.

The application of the aforementioned reading procedure, encompassing morphological transformations and their repercussions in the past, in the press and, currently, on social networks, more specifically on Instagram, will be carried out on selected segments of the Rio Orla Project. It sought to reveal the different forms of appropriation and visualization of bike lanes and the boardwalk, highlighting the transient urban fabric of the set of physical routes punctuated by virtual records of “instagrammable” images, overlaid on the consolidated structure of the chosen segments.

- Procedures

The research operationalization involved field observation, documentary review in urban planning institutions and newspapers from the time of the project’s construction, and the selection of criteria as search keys on the Instagram social network.

The selection of content retrieved from the social network, related to the analyzed segments, adopted the application’s search tool, based on the location of its beaches. Beaches in Copacabana, Ipanema, and São Conrado were observed to interpret the three studied segments. Location is an optional piece of information that users may indicate as the places they were at the time of media creation or that have a relation to their posts. Thus, it is possible to use location as a tag to find content related to the debate in this work.

Additionally, this procedure includes the classification by the network itself of the most recent content at the time of the search and also the selection of scene records that may represent the everyday appropriation of their boardwalks, kiosks, bike lanes, and environmental dimension.

The Rio Orla Project: bike lanes, kiosks, and enjoyment

The Rio Orla Project begins with a national public competition, launched in June 1990 by the City of Rio de Janeiro, coordinated by the Institute of Architects of Brazil/RJ, IAB-RJ, under the title “Preliminary Study for the Urban Design of the Maritime Waterfront of the City of Rio de Janeiro”. The works took place from early 1991 until the Rio 92 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development.

The mayor who assumed office in 1989, Marcello Alencar, found the City in a state of shock due to the bankruptcy declared by the previous mayor, initiating a program of street cleaning and maintenance to restore urban living standards. The director of IPLANRIO, co-author of this article, comments on the context of the time of the works in an unpublished technical report produced within IPLANRIO:

In terms of planning, in order to recover the population’s enthusiasm for the city, the idea arose to restore emblematic places such as Cinelândia, Lapa, Uruguaiana Street, Presidente Vargas Avenue (all in Downtown!!) and, in a bold and profound manner, the waterfront from Leme to Ponta (Strozenberg, 1991).

These were non-pressing, unnecessary interventions, especially in view of the municipal services calamity. However, it is observed to this day that the population appreciates having their city improved and beautified, as long as they can use it, because it is not about castles, courthouses, etc. The waterfront from Barra to Pontal was practically not urbanized, but would touching the consolidated waterfronts such as Copacabana, Ipanema, and Leblon be a sacrilege? Hence, the easy fruition of the criticism.

The Rio Orla competition established two groups of beaches. Group A comprised the beaches of Barra, Recreio, and Pontal, spanning 20 km with little urban intervention, while Group B comprised the beaches of Leme, Copacabana, Ipanema, Leblon, and São Conrado, spanning 9.7 km with defined urbanization.

In this article, we will concentrate on the analysis of the post-Rio Orla development of the Group B beaches, located in the South Zone, as illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1: Publicity posters used in the project presentations to the residents.

Source: IPLANRIO

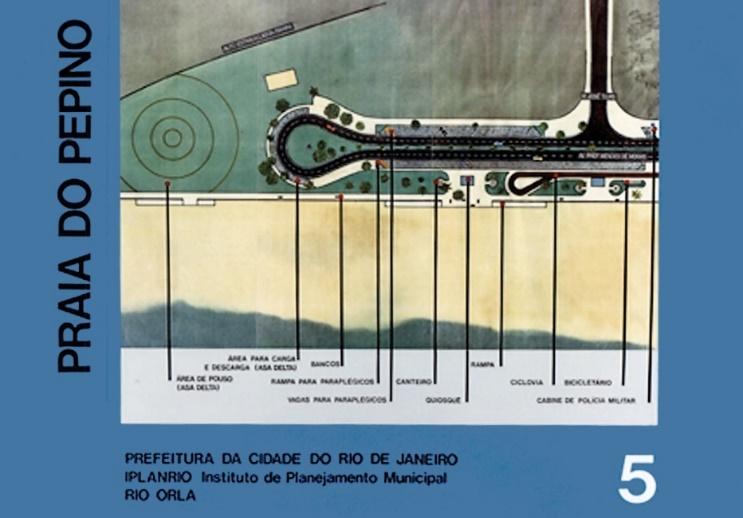

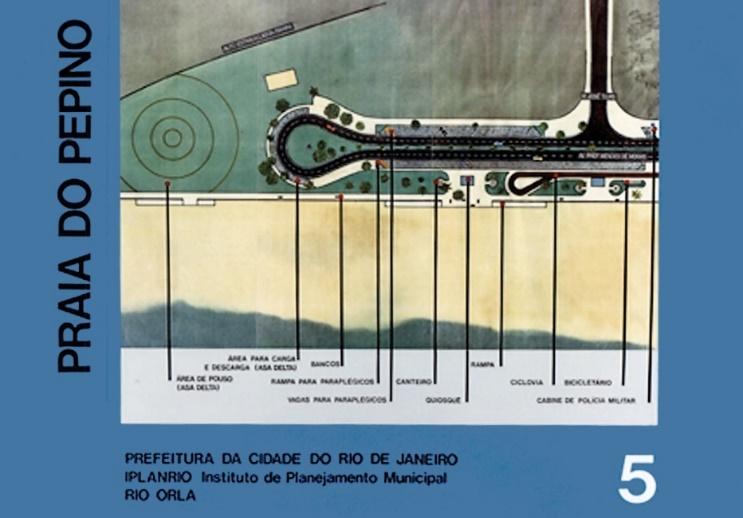

Figure 2: Project board for the São Conrado beach.

Source: IPLANRIO

- Points of Attention in the Urban Design Project

The implementation of large public urban intervention projects has been a constant in modern urbanism. Each of these projects seeks what Yannis Tsiomis describes as the reconquest of the city “against the simplification of functions in which concepts that become architectural themes are reintroduced: identity, centrality, articulation, connection, flexibility, mobility” (Rego; Andreatta, p. 104).

The project addressed the implementation of the bike lane, improvements to sidewalks and landscaping, lighting, installation of kiosks, traffic studies, parking, and accessibility. The competition notice defined the following items:

- The solutions should prioritize pedestrians, even if necessary to the detriment of automobiles;

- The works, except for the kiosks, could not encroach upon the sand; each beach should provide external pockets for events and sports activities;

- A bike lane adjacent to the boardwalk should be provided on all beaches;

- Standardization of commercial points along the beaches, in the form of kiosks, equipped with water, sewage, electricity, and telephone.

Various contributions to the project were made by neighborhood associations and specific thematic groups: improvement of the fishermen’s path by the Leme Residents’ Association; a delta-wing landing area in São Conrado by the Free Flight Club; loading and unloading parking for windsurfers by the Windsurf Association; and ramps for paraplegics by the Cerebral Palsy Association.

The characteristics of the main interventions were as follows: On the boardwalk from Leme to São Conrado, beachfront parking was prohibited, freeing the view of the beach and “bringing” the boardwalk and beach closer to the population. The view of the beach became accessible to pedestrians.

The solutions found for each location were a project concern, with parking to the left of the travel lane in Leme and São Conrado and in the central strip in Ipanema and Leblon. This solution was not possible in Copacabana because the central strip, a project by Burle Max, is heritage-listed (fortunately).

In turn, the city’s first bike lane was implemented, equipped with signage, crossing stripes, and adaptations for people with disabilities and strollers.

The signage on the bike lane was fundamental in minimizing conflicts at pedestrian crossings. A crossing module was created next to traffic lights, with the pedestrian crossing aligned with ramps for people with disabilities and strollers, as well as cyclists. The pavement signage guided the cyclist.

In Leme and Copacabana, the space for beachfront parking was occupied by the bike lane. The removal of parking along the beach sidewalk for the implementation of the bike lane in Ipanema and Leblon was much more complex since the boardwalk does not have the same width. The project’s initial conception was to narrow the generous sidewalk adjacent to the buildings by bringing the travel lanes closer. However, due to the categorical reaction of residents from Vieira Souto and Delfim Moreira avenues, it was decided to narrow the central strip and redo the intersections, turns, and slip roads. These changes resulted in the removal of trees and the replanting of others after the works, and they were the target of severe criticisms and campaigns against the project. It was considered excessive! And for what? Bicycles!!!

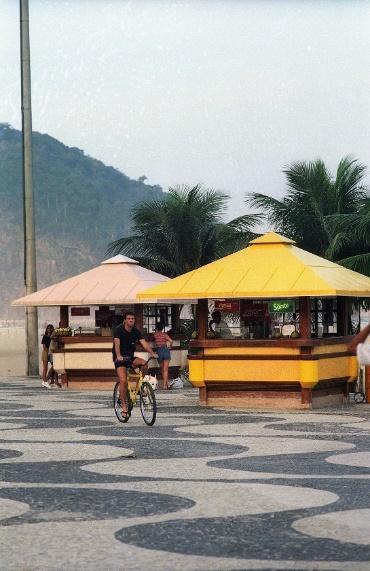

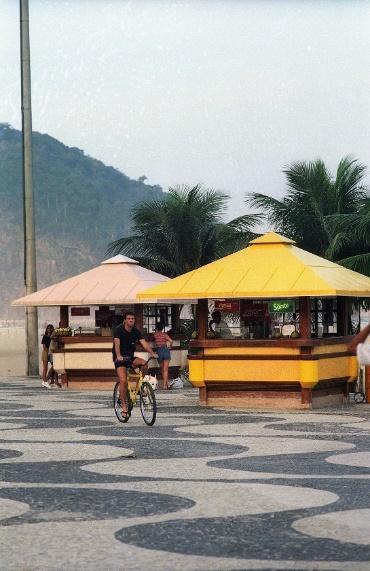

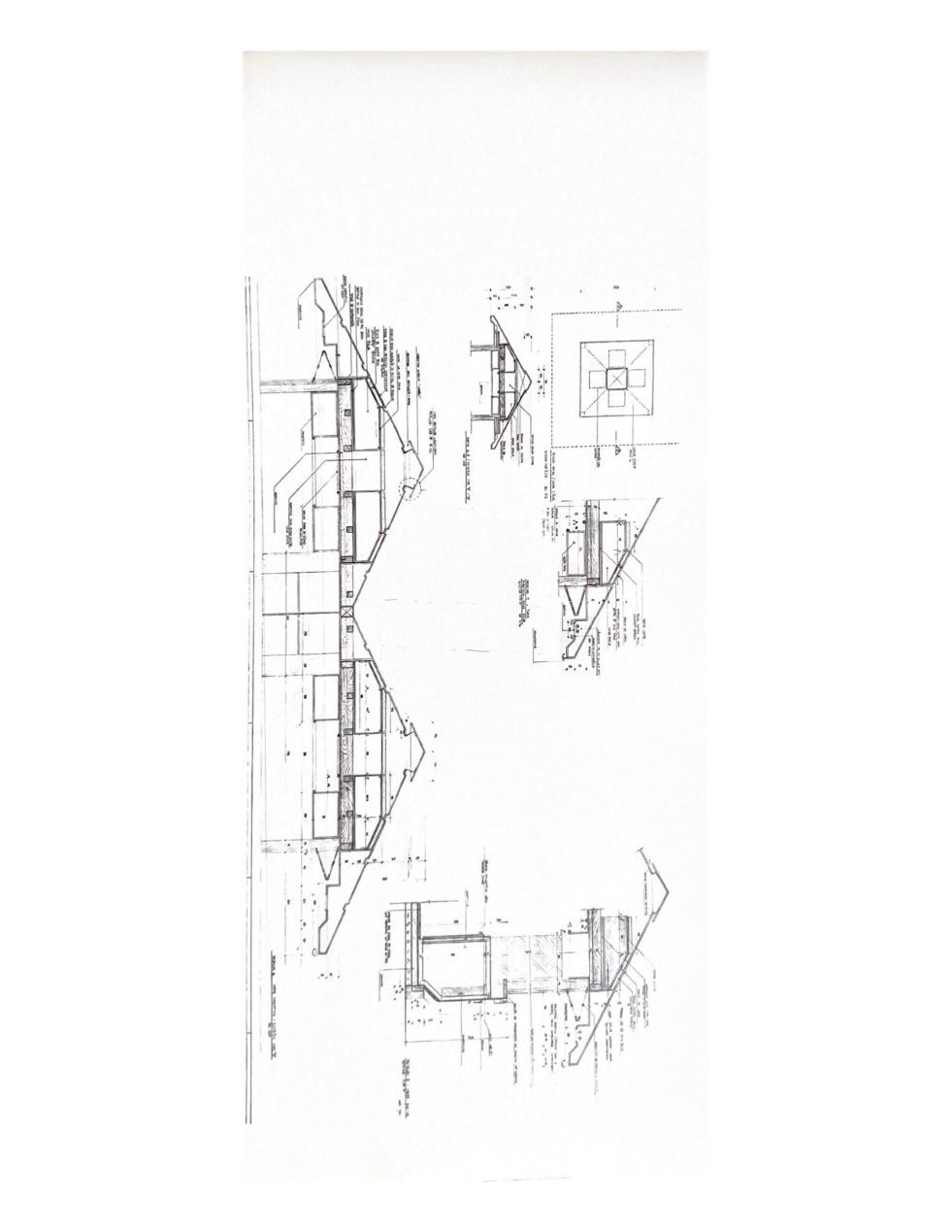

Regarding the kiosks, they replaced trailers and small carts with facilities equipped with water, sewage, and electricity, resulting in visible gains in hygiene and cleanliness. The original model of the kiosk on the South Zone beaches was made of fiberglass, with an area of 5.06 m² (2.25m x 2.25m), installed approximately 125m apart (near the axes of the cross streets).

Meetings were held with the community after the competition results to refine some items. One of the proposals was the explicit prohibition of commercial neon signs on the kiosks, which indeed occurred, leaving no tables or chairs, even so as not to compete with the restaurants on the inner side of Avenida Atlântica.

The replacement of trailers and small carts, Figures 3 and 4, was a negotiation process managed by IPLANRIO which, after some opposing manifestations, constituted committees of kiosk owners with city officials to reach consensus. At that time, there were 79 points in Leme and Copacabana, 61 in Ipanema and Leblon, 40 in São Conrado, and 290 in Barra, a total of 470, for a total of 306 new kiosks. The difference was absorbed by members of the same family or corporate association.

Figure 3: Original model of the kiosk in the South Zone, without tables, chairs, or neon signs, and the kiosk design.

Source: Authors’ Archive

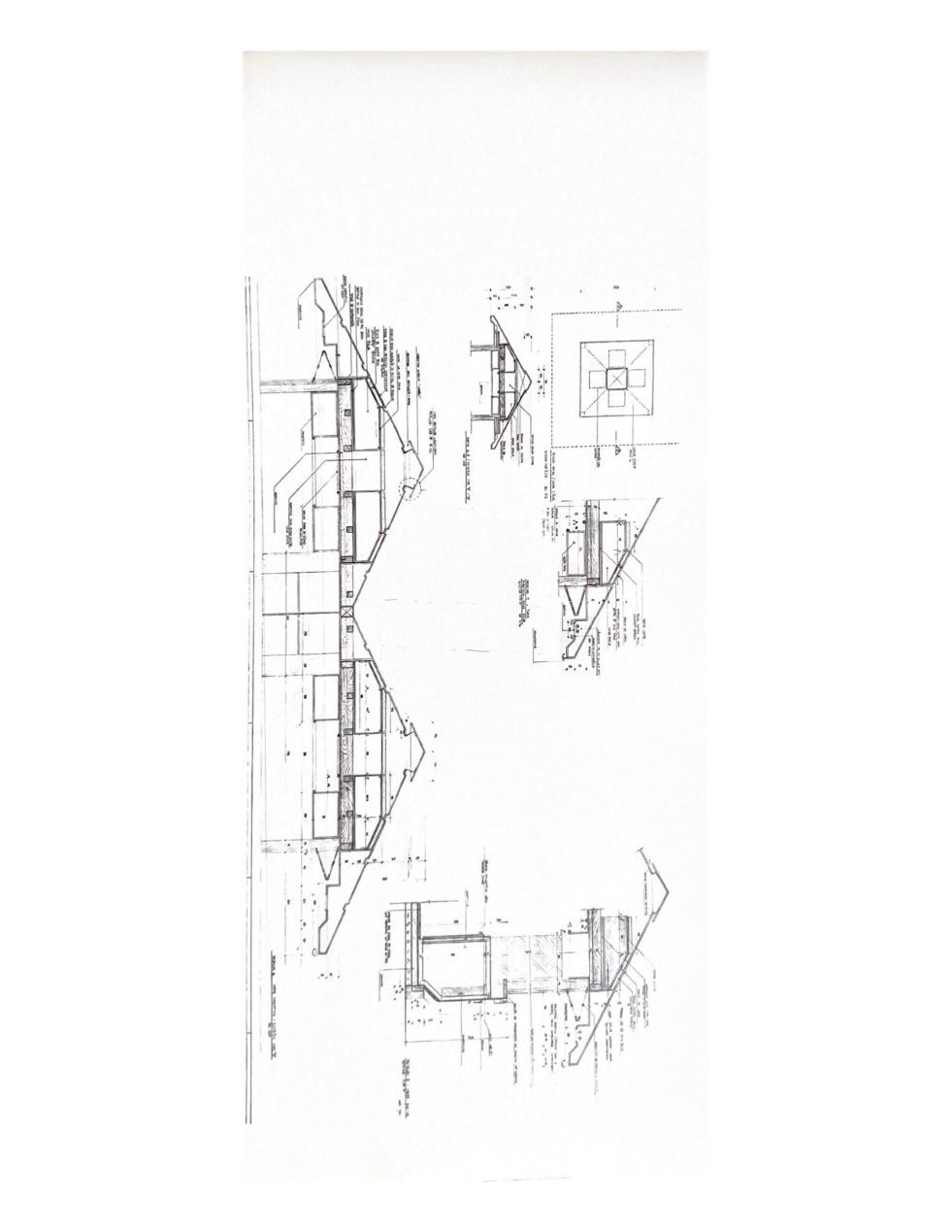

Figure 4: Technical drawings of the original model of the kiosk in the South Zone.

Source: IPLANRIO

In São Conrado, Figure 5, the beachfront parking was relocated to the other side, adjacent to the buildings, enabling the implementation of the bike lane. The boardwalk was widened to facilitate walking and running, while maintaining its physical structure supported by the existing retaining wall, which has a significant elevation difference compared to the sand.

The kiosks in São Conrado were positioned according to the use of the segment. The location of the two major hotels of the time was noted: the Hotel Nacional and the Intercontinental. There is a large unused area belonging to the Gávea Golf and Country Club. Some buildings are situated in the center of the lot, fenced and closed, facing inward. In the area of Praia do Pepino, a landing field for delta wings and paragliders was created, surrounded by a plaza with children’s play equipment. The Clube São Conrado de Voo Livre has its headquarters on site.

Figure 5: Design of the project in São Conrado.

Source: IPLANIO

Public lighting improvements were made by installing tall light poles in the central strip and creating specific lighting for the beach sands, enabling nighttime football and volleyball games. In Arpoador, a light pole was installed that allowed surfers to remain on the beach at night.

As for landscaping, it was considered that all existing species should be preserved, taking advantage of the vegetation’s maturity. Only those that were deteriorated were replaced.

In the final assessment, Copacabana did not change the number of trees, Ipanema lost 123 (from 285 to 162), and São Conrado gained 127 (from 163 to 290). The reduction in Ipanema, as a result of narrowing and the use of the central strip for parking, caused significant controversy, as will be discussed.

Evolutionary Analysis: Appropriations and Changes

The vast physical scale of the studied area and, consequently, of the road network and its interconnections with the networks that are daily configured through transient routes, made illustration difficult and necessitated, for the purposes of this article, a descriptive presentation of the results (Figures 6, 8, and 9).

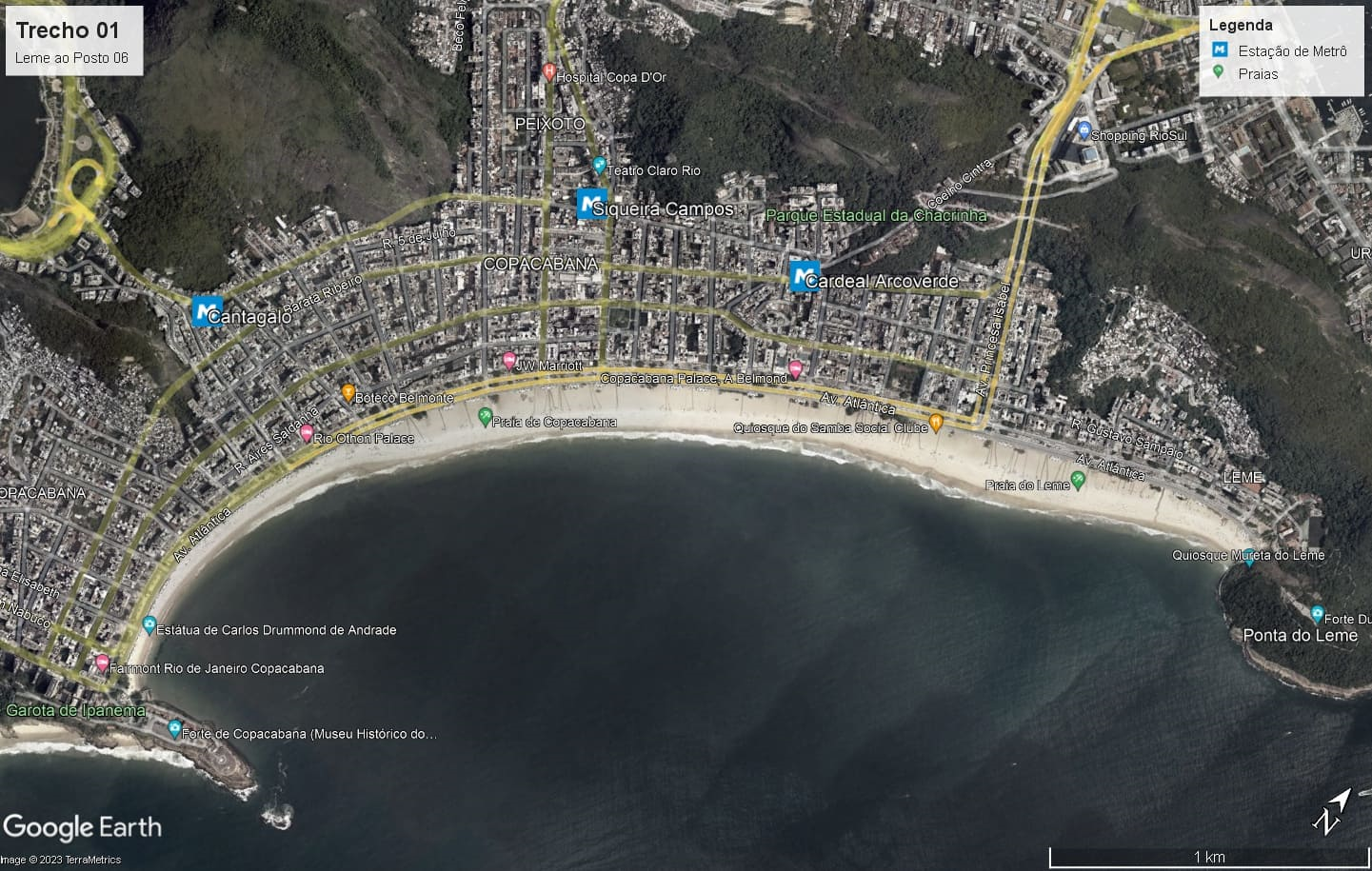

- Segment 1 – from Leme to Posto 6

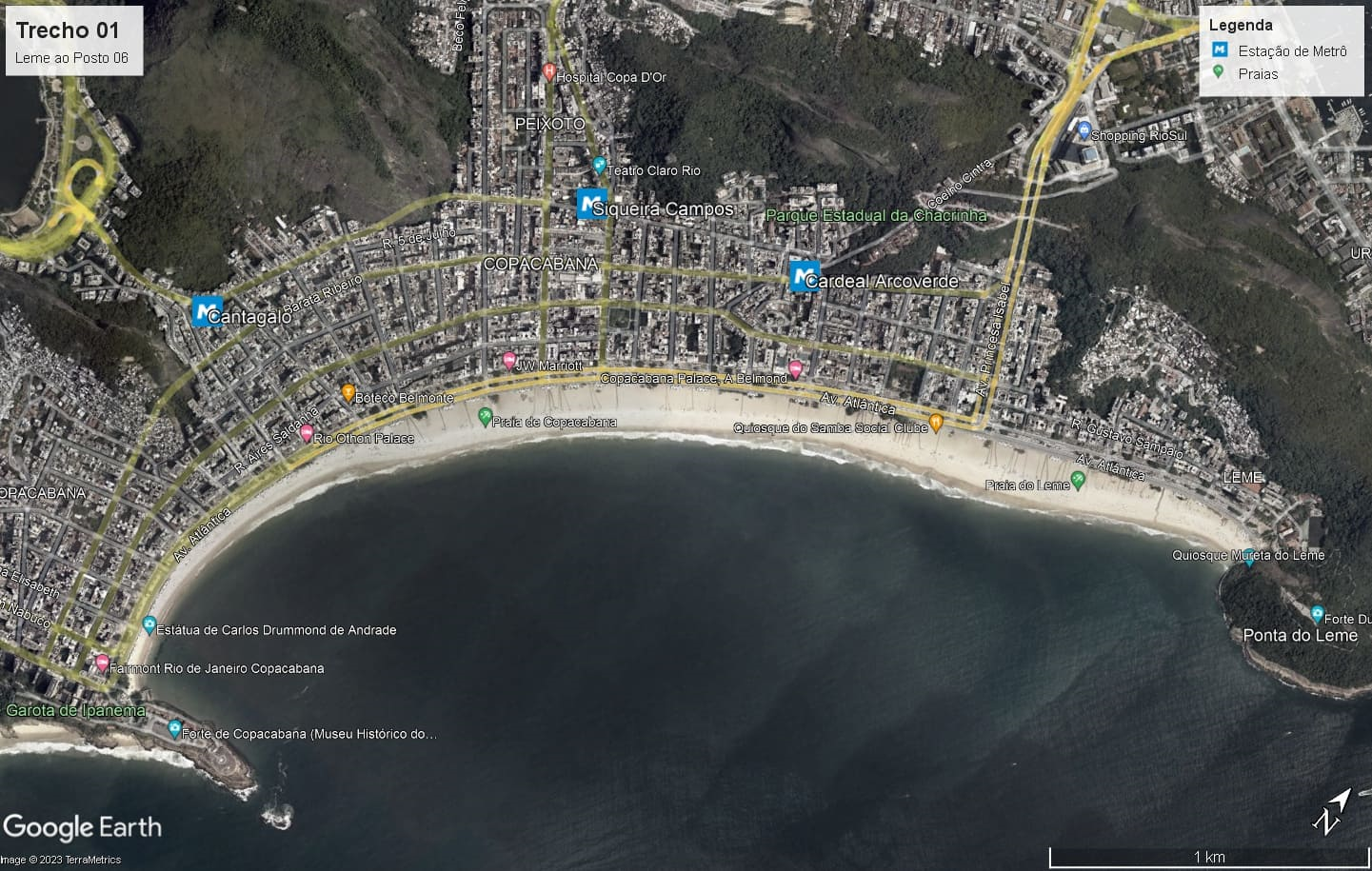

Figure 6: Beaches of Leme and Copacabana, highlighting the three metro stations.

Source: Google Earth (online)

4.1.1 Morphological

Posto 6, the stretch of the waterfront that connects Leme to the far end of Copacabana, is a major attraction in the city. It is nourished by the memory of past privileges and the privileged, still evident in the form of the luxurious Copacabana Palace Hotel.

It encompasses 100 blocks, 78 streets, 5 avenues, 6 alleys, and 3 slopes, covering an area of 7.84 square kilometers. The longest road is Avenida Atlântica, measuring 4,150 meters. Between 1920 (with 17,000 inhabitants, representing 1.5% of the city’s total population) and 1970 (with 250,000 inhabitants, or 6% of the city’s total population), the neighborhood’s demographic growth was an astonishing 1,500%, while the city as a whole grew by 240% during the same period (O’Donnell, 2013). According to the virtual encyclopedia Wikipedia, Copacabana is considered one of the most famous and prestigious neighborhoods in Brazil and one of the best-known in the world, often referred to as the “Little Princess of the Sea” and the “Heart of the South Zone.” It would be the most populous neighborhood in the South Zone, according to the 2010 census, with more than 140,000 inhabitants, of which about one-third (approximately 43,000 inhabitants) is composed mainly of elderly people aged 60 or older, distinguishing it as the “oldest” neighborhood in the country. The significant population loss between 1970 and 2010 is accompanied by several signs of decay, pointed out in the English tourist guide Time Out (2024) as a warning to its readers. The ground floors of most buildings located along the main axes of the neighborhood feature a large number of shops selling various products, along with traffic congestion, recurring incidents of theft and robbery, and prostitution. Even so, the nightlife is very lively with excellent restaurants, small bars, in addition to the 4 kilometers of beach.

The evolution of the kiosks in Copacabana and the use of the boardwalk represent the most intense change in the entire Rio Orla project. The initial limitation to a simple point of sale for soft drinks and sandwiches with standing service was gradually modified, first with the permission to have tables and chairs, then with illuminated signs displaying the names of the kiosks and commercial brands.

This set of morphologically interrelated attributes is distributed differently along the neighborhood’s two parallel structuring axes, Avenida Atlântica and Avenida Nossa Senhora de Copacabana. Supported by the three metro stations and numerous bus lines that provide access for residents and visitors from other parts of the city, in addition to the bike lane, they collectively form the network of routes, diverse and transient, of the residents’ everyday paths that support the extraordinary routes of visitors. They connect the fabric of the neighborhood to the waterfront.

4.1.2 Cultural

Since 1980, the neighborhood has hosted the Copacabana Seafront Night Fair of Handicrafts and Art, located at Posto 5. It opens at 5 p.m., shortly before nightfall. Another tourist attraction is the Copacabana Fort, located at Posto 6. The Museum of Image and Sound (MIS), which was intended to replace the Help nightclub since 2010, currently remains under stalled construction, with fencing that detracts from the attractiveness of that stretch.

Beyond New Year’s Eve, Copacabana Beach serves as the setting for numerous artistic and sporting events, occupying the space with structures for major happenings stretching from Avenida Princesa Isabel to beyond the Copacabana Palace Hotel, along Rua Fernando Mendes.

The area of the beach in front of the Copacabana Palace Hotel has gradually become a venue for events. At the hotel, the pergola with the restaurant/bar surrounding the pool diminishes the importance of its relationship with the beach.

The Copacabana Palace asserts its appropriation of the beach when it serves its own interests. For instance, during the 2016 Olympics, with official games held right in front of it, a catwalk was constructed over Avenida Atlântica linking its balcony to the games arena. On the occasion of its 100th anniversary in August 2023, it planned a large free show on a huge stage on the sand.

4.1.3 Connectivity

The Rio Orla bike lane was the greatest contribution to the gradual increase in bicycle use in the city, especially for leisure, sport, and transportation. The cycling network continues to expand. Interestingly, the bike lane was one of the most criticized aspects of the project, costing the government dearly to support the introduction of this new mode of transportation.

Another aspect of mobility is the evolution of the metro in this stretch. The arrival of the metro, Cardeal Arcoverde Station, in 1998 had a strong impact in Copacabana. In the same year, the metro also completed Line 2, Estácio-Pavuna, enabling travel between Estácio and Cardeal Arcoverde. Rodolfo Dantas Street is the route closest to the beach from this station, right on the corner of the Copacabana Palace Hotel.

In 2003, Siqueira Campos Station was inaugurated, and in 2007, Cantagalo Station was opened, completing the three stations that serve the neighborhood. However, the metro only began operating on Sundays from 2004 onward. Buses, which were crowded, were the only form of public transport on Sundays, and they continue to be important, especially in the summer, with a reduced number of vehicles on various lines that connect with the North Zone via the Rebouças and Santa Bárbara tunnels, or even the Flamengo landfill. They are also repeatedly targeted by police magazines.

Pedestrian flows exiting the metro form routes to the points closest to the boardwalk, with varying intensities at different times of the day; these flows disperse on the beach sand and reconnect on the boardwalk. GEHL (2013) emphasizes that one of the great attractions of public space is seeing others, watching people having fun in their own way. Thus, these passage and concentration points attract attention in themselves, especially from external visitors.

4.1.4 Management

The kiosk concessionaire obtained authorization from the City Hall to alter its model. It came to include restrooms and a kitchen in the basement, as well as ample space for tables, chairs, and awnings (some equipped with sofas and armchairs), with a significant occupation of the public area on the boardwalk, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Current kiosk with ample occupation area.

Source: Authors’ Archive

This modernization was completed in Copacabana in preparation for the 2014 World Cup. The kiosks transformed into restaurants. The distance between them became varied according to their attractiveness, accompanied by an increase in activities from independent vendors on the boardwalk selling non-food products. Sand sculptures link some of these areas with fabricated landscapes, apparently similar, as well as street vendors marking segments of the routes.

Thus, the boardwalk began to have a life almost independent of the inner sidewalk of Avenida Atlântica, which continues to have a strong presence of restaurants, most of them very old. As no complaints arose about the increased proportion of kiosks, which evolved from simple standing points of sale to establishments with significant competition, it is presumed that there is demand for all, catering to a stratified public.

Among the clientele, the strong presence of tourists stands out, both on one side and the other of Avenida Atlântica. In Leme and Copacabana, there are several beachfront hotels and numerous ones along the cross streets.

- Segment 2 – from Arpoador to Leblon

Arpoador maintains its characteristics as a protected enclave, yet with easy pedestrian access via Avenida Vieira Souto or through the Garota de Ipanema Park and Francisco Otaviano Street. It absorbed the growth of a small restaurant at the entrance to the pedestrian street.

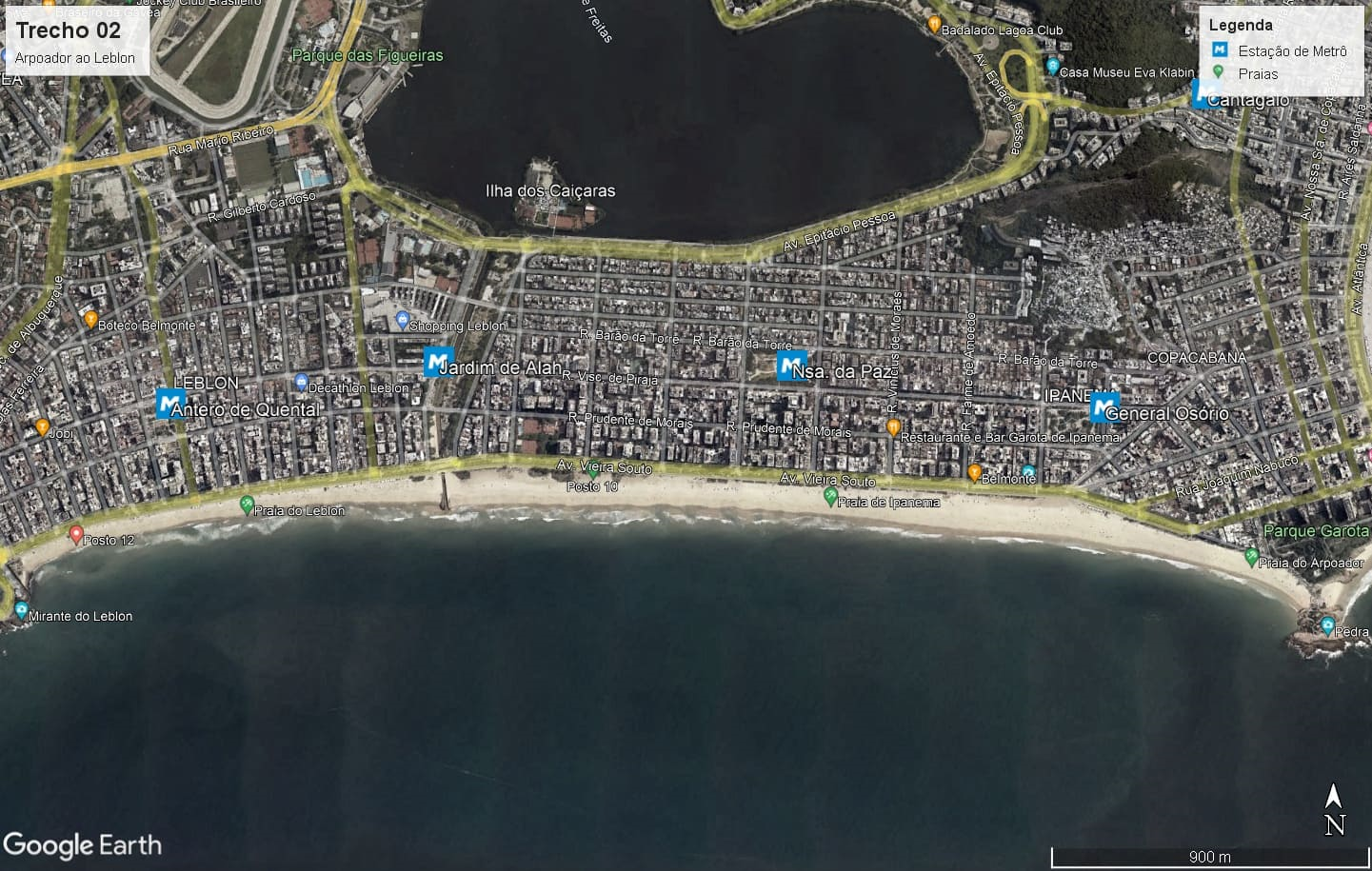

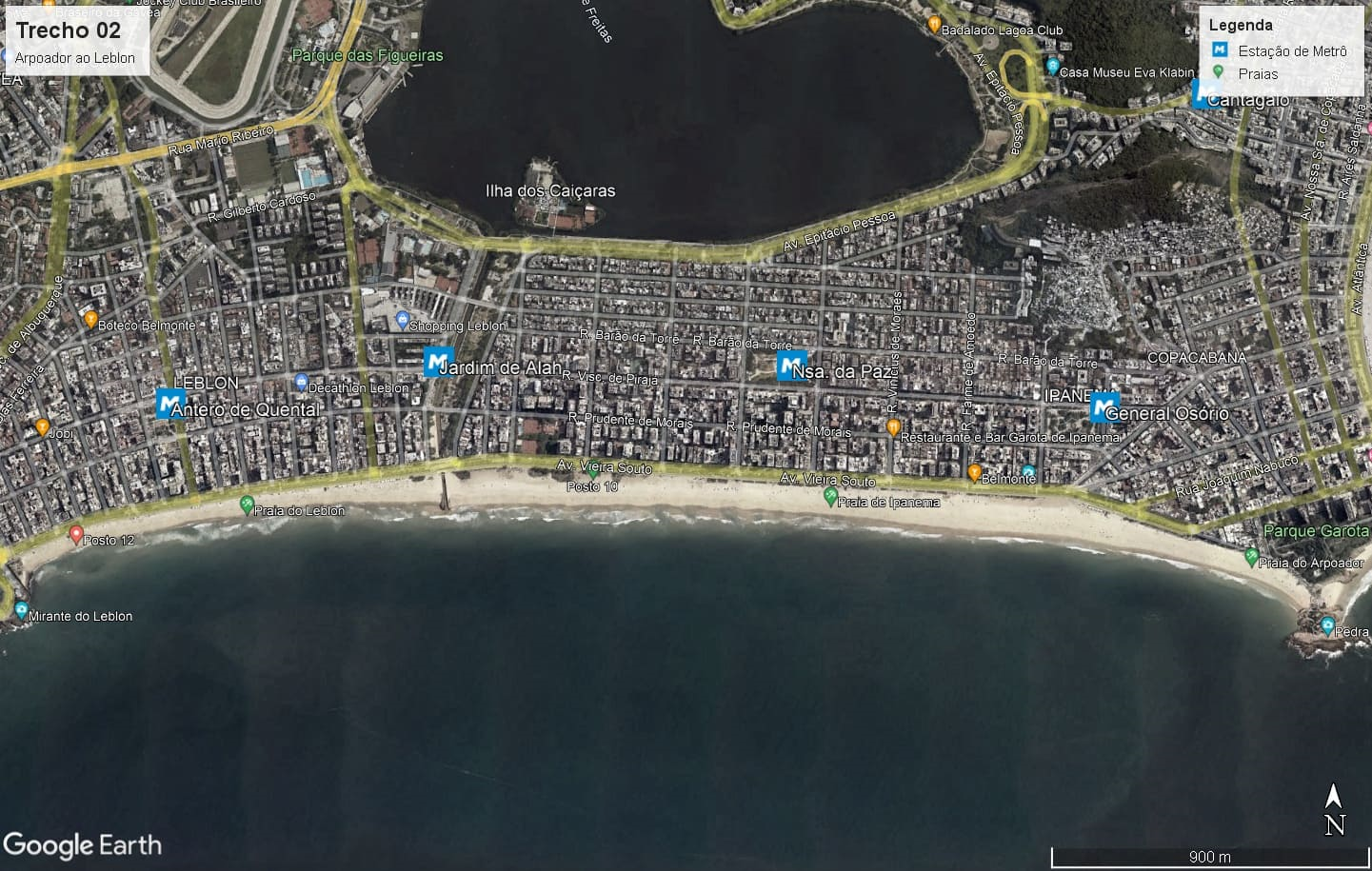

Figure 8: Arpoador, Ipanema, and Leblon beaches, with the 4 metro stations.

Source: Google Earth (online)

4.2.1 Morphological

With the completion of the Rio Orla project just before the Rio '92 Conference, the waterfront from Leblon to Copacabana was revitalized. With no parking areas close to the shore, bike lanes began to gain more users than initially anticipated. The city was experiencing a moment of increased environmental, climatic, and natural awareness. Seizing the opportunity, the City Hall implemented a program to create leisure areas on Sundays and public holidays by closing the lanes adjacent to the promenade and bike path to vehicular traffic. It became a remarkable extension of the promenade, dedicated to pedestrians, cyclists, strollers, roller skates, and scooters. Since 1992, this leisure area along the waterfront has been widely used, including for marches and demonstrations.

4.2.2 Management

The 2016 modernization of kiosks has not yet reached all facilities. The law of supply and demand continues to prevail.

The Fairmont Hotel, located on Av. Atlântica at Posto 6, and the Fasano Hotel, on Av. Vieira Souto in Ipanema, both five-star establishments, attempted to occupy kiosks directly in front of their premises, using the hotels' own names and offering special services to their guests, although not exclusively. This was a strategy to bring them closer to the promenade.

These initiatives were discontinued due to the pandemic, and their impacts have not been studied by this group. The prestige of the Fasano name lent the kiosk a distinctive “genetic capital,” positioning it as the finest restaurant along the beachfront.

4.2.3 Cultural

The promenade, though it receives some tourist presence, is mainly used by local residents for walking, despite sharing its appeal with the Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas waterfront. There are also retail vendors and sand sculptures. Events on these beaches are limited and do not rely on large setups. Recently, political demonstrations have taken place on the beach sand, with images recorded and shared on social media.

4.2.4 Connectivity

The same split in demand seen at the Lagoa is present on the Ipanema and Leblon bike paths, especially for recreational use. On the inner sidewalk, Copacabana’s urban pattern is not replicated. There is no culture of strolling. Few hotels remain (some have recently closed), few restaurants, and a cultural center that does not engage with the beach. The Hippie Fair at General Osório Square (since 1975) and the activity at Nossa Senhora da Paz Square do not involve the waterfront.

The metro arrived at General Osório Station in 2009 via Line 1 from Tijuca, and in 2016, for the Olympics, via Line 4 from Barra, adding three more stations in the neighborhoods: Nossa Senhora da Paz, Antero de Quental, and Jardim de Alah.

4.2.5 Economic

The promenade, with a moderate presence of tourists, is heavily used by residents for walking. There are also retail vendors, sand sculptures, and other attractions.

On the inner sidewalk, Copacabana’s model is not reproduced. There is no strolling culture. Few hotels (some of which have recently closed), few restaurants, and a cultural center that does not interact with the beach. The Hippie Fair at General Osório Square (since 1975) and the movement at Nossa Senhora da Paz Square do not involve the beachfront.

Gastronomy is a strong draw, but it is concentrated in the inner and side streets of the neighborhoods, including the Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas area. The planned renovation of Jardim de Alah (announced in August 2023) aims to reinforce this trend.

- Trecho 3 – São Conrado

Figura 9: Imagem de Satélite da Praia de São Conrado.

Fonte: Google Earth (online)

4.3.1 Environment

São Conrado Beach is characterized by its light, soft sand and strong waves, which are the main attraction for local surfers. Unfortunately, the beach is often unsuitable for swimming due to pollution. However, the wide strip of sand is favorable for sports activities.

4.3.2 Morphological

The interaction between the promenade and the opposite side of the avenue is either null or severely weakened due to the morphology that defines this part of the neighborhood. The blocks are divided into large plots occupied by tall residential buildings, all enclosed by high fences, electronic gates, and surveillance cameras. Likewise enclosed and monitored, the large plot of the golf club occupies half of the beachfront extension. The relationship with the beach is seemingly reduced to mere contemplation.

The Hotel Nacional, one of the few attractions in the neighborhood, has recently reopened and still stands out. Designed by architect Oscar Niemeyer and featuring gardens by landscape designer Burle Marx, its architecture is an almost mandatory tourist site in the city. However, it does not promote or encourage interaction with the beach, and therefore does not establish any connection with the promenade, the bike path, or the kiosks.

4.3.3 Social

The population of São Conrado presents a stark social contrast between the beachside elite condominiums and the poor communities of Rocinha and Vidigal, unlike the more integrated profiles of other neighborhoods studied. Coexistence here is under surveillance.

4.3.4 Economic

The spacing between kiosks varies. Near the landing area for hang gliders and paragliders, four closely grouped kiosks create a hotspot offering snacks for athletes and visitors. Along the rest of the beach, however, the spacing increases significantly and is supplemented, when necessary, by street vendors.

4.3.5 Connectivity

The collapse of the Tim Maia bike path, along Av. Niemeyer, disrupted the route. It is also disruptive at the level of collective perception, a scar with repercussions across the other dimensions of the study.

The Intercontinental Hotel, closed since 2020 and now fenced off with hoarding, has been announced for conversion into residential units. For now, however, it further impoverishes the connection between this part of the avenue and the beach.

This stretch of the coastline draws its energy from the hang gliding and paragliding activity located at the end of the route.

Repercussions, Press, and Instagram

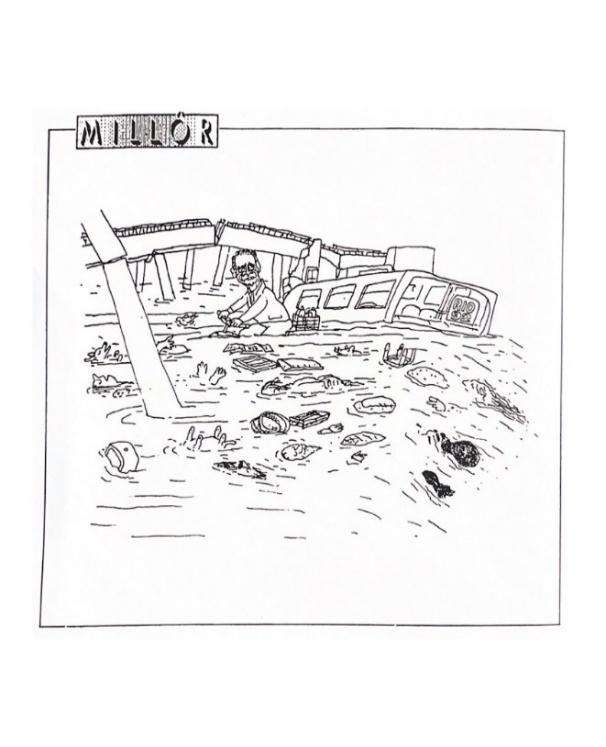

Large-scale urban interventions that remove sociocultural practices of environmental appropriation for beach leisure, deeply rooted in the everyday lives of many people, and replace them with new elements, even if intended for the same purpose (enjoyment), tend to face opposition and generate disputes. When such changes personally affect a public opinion-forming journalist, specifically Millôr Fernandes, the dispute becomes a battle portrayed in the newspapers of the time, as illustrated in Figures 10 and 11.

Project features that were initially condemned with strong criticism were later appropriated and expanded. The press controversy in the 1990s, with the pace and duration of the debates, increased visibility and enhanced the project's attractiveness.

Figures 10 and 11: Two cartoons by Millôr Fernandes published in the Jornal do Brasil.

Source: Jornal do Brasil

Although the Rio Orla Project followed the public presentation process with various sectors of society, mainly residents' associations in the beachfront neighborhoods and other users, it sparked significant media controversy.

The construction work in the South Zone bothered much of the population. Started in the summer of 1991, they were in full swing by the summer of 1992, involving parking relocation, works on the promenade (installing water and sewage for the kiosks), and in front of the promenade (bike paths).

Journalist Millôr Fernandes, a prominent resident of Ipanema and critic of the project, published numerous cartoons in his column in Jornal do Brasil. Chico Caruso followed suit. The bike path, tree removals, disruptions, and the mayor himself were favorite topics.

Alfredo Sirkis, then a city councilman from the Green Party, was the main defender of the bike path and frequently commented at IPLANRIO meetings that Millôr attacked people in that way, including himself, as a supposed environmental traitor. His articles were so well-written they made you almost angry at yourself, but the criticism, he argued, was baseless.

The impact of these cartoons was significant as they aligned with the views of many readers, and stood out due to the quality of the drawings, the fame of the authors, and the relevance of print media at the time. Nevertheless, it is important to reflect on the very essence of humor in human life.

A person, as an active subject of perception in the process of interpersonal relationships, is inclined toward positive emotions. Since humor is a form of communication and a phenomenon of both social and individual consciousness, it must be acknowledged as having a humanistic orientation. (Lazebna, 2022, p.2)

The author further explains that humor helps relieve stress and “may even help solve complex life situations in the era of globalization” (Lazebna, 2022). Humor would allow us to combat depression, doubt, and stress, as well as resist the pressures of excessive competitiveness.

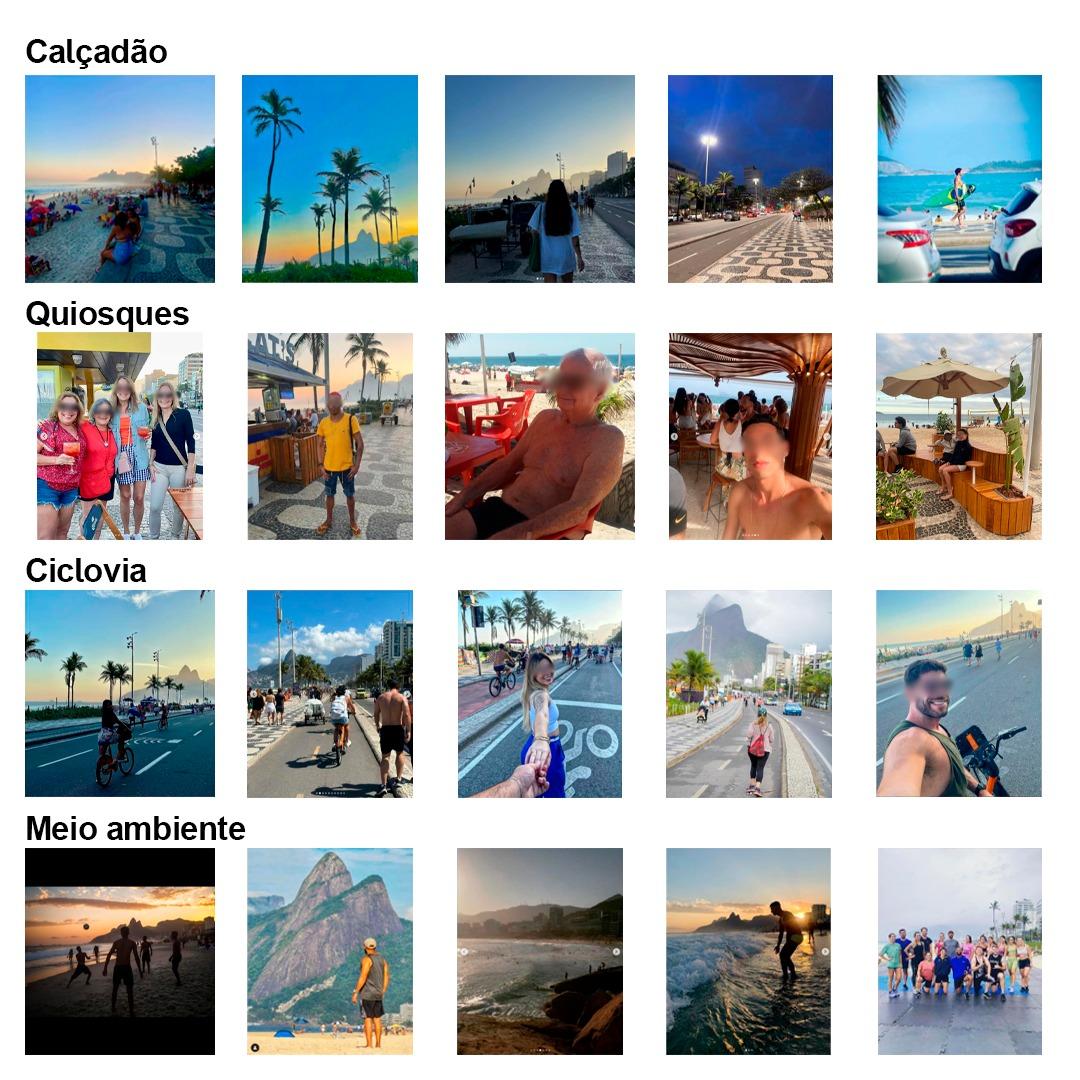

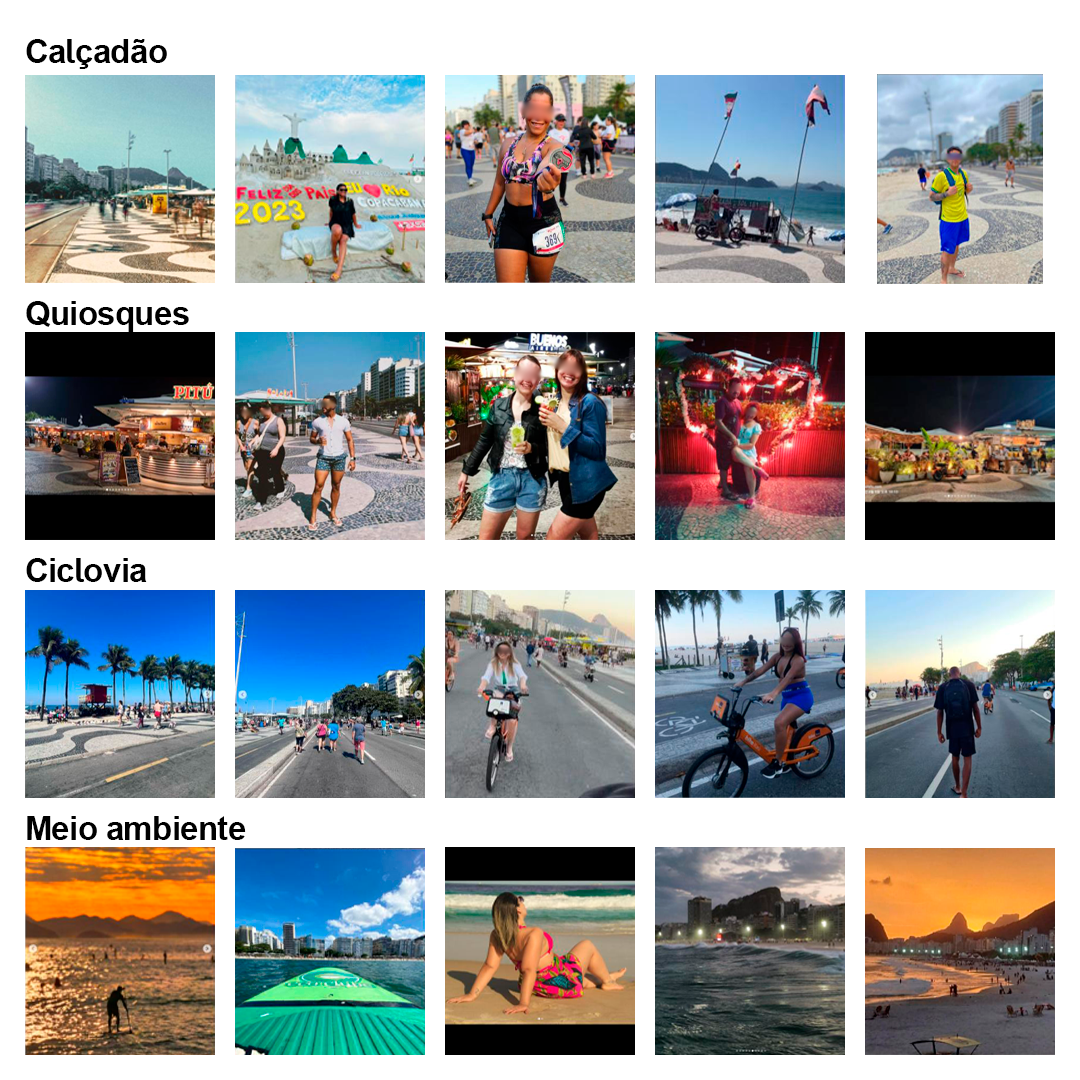

- Instagram – Leme and Copacabana Segment

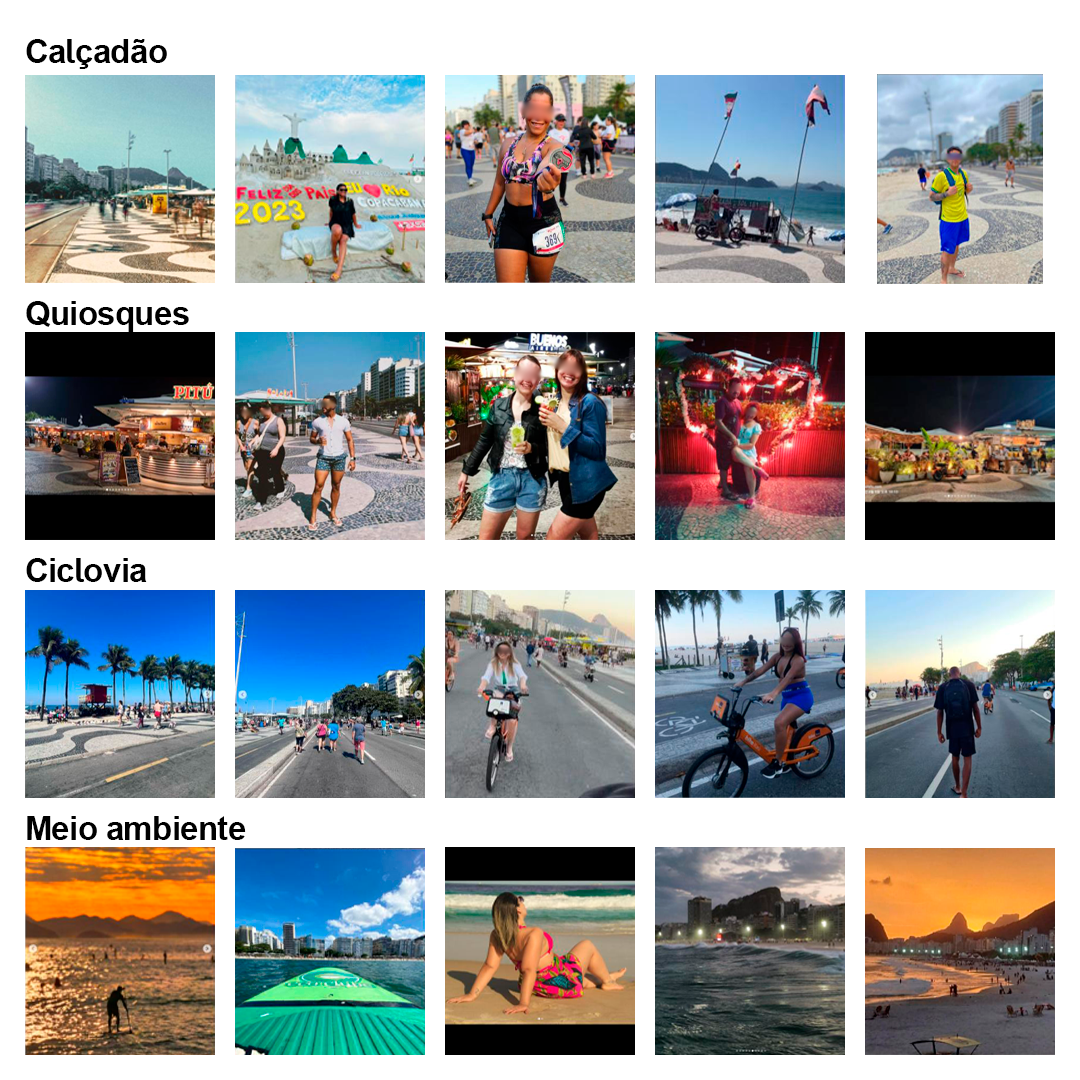

Figure 12: Grid of photos tagged in Leme and Copacabana on Instagram.

Source: Instagram (online)

The images analyzed from Instagram, in Figure 12, highlight various temporary uses primarily structured along the length of the promenade, from Pedra do Leme to Forte de Copacabana. The kiosks, bike lane, and environmental dimension appear most frequently as part of this public space experience.

As one of the neighborhood’s main edges, the promenade hosts a range of activities in these records, making it an important resource for connectivity and sociocultural interaction. Privileged by its popular visibility and tourism, the waterfront hosts a diverse set of events such as concerts, races, and political demonstrations. These feed into the symbolic imagery and attractiveness of this destination and leave traces on various scales of economic agents, uses at different times of day, and identity representations revealed in these online posts.

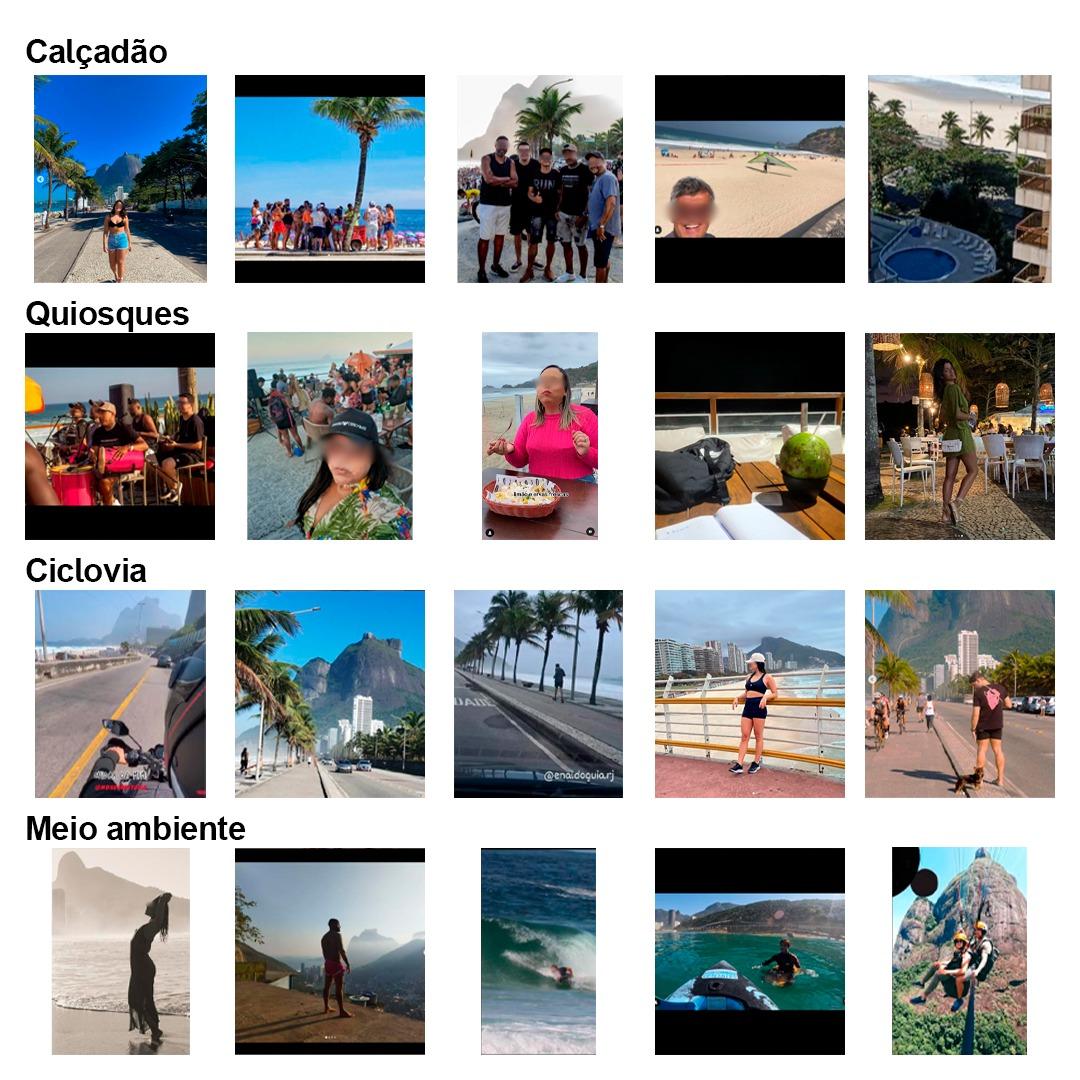

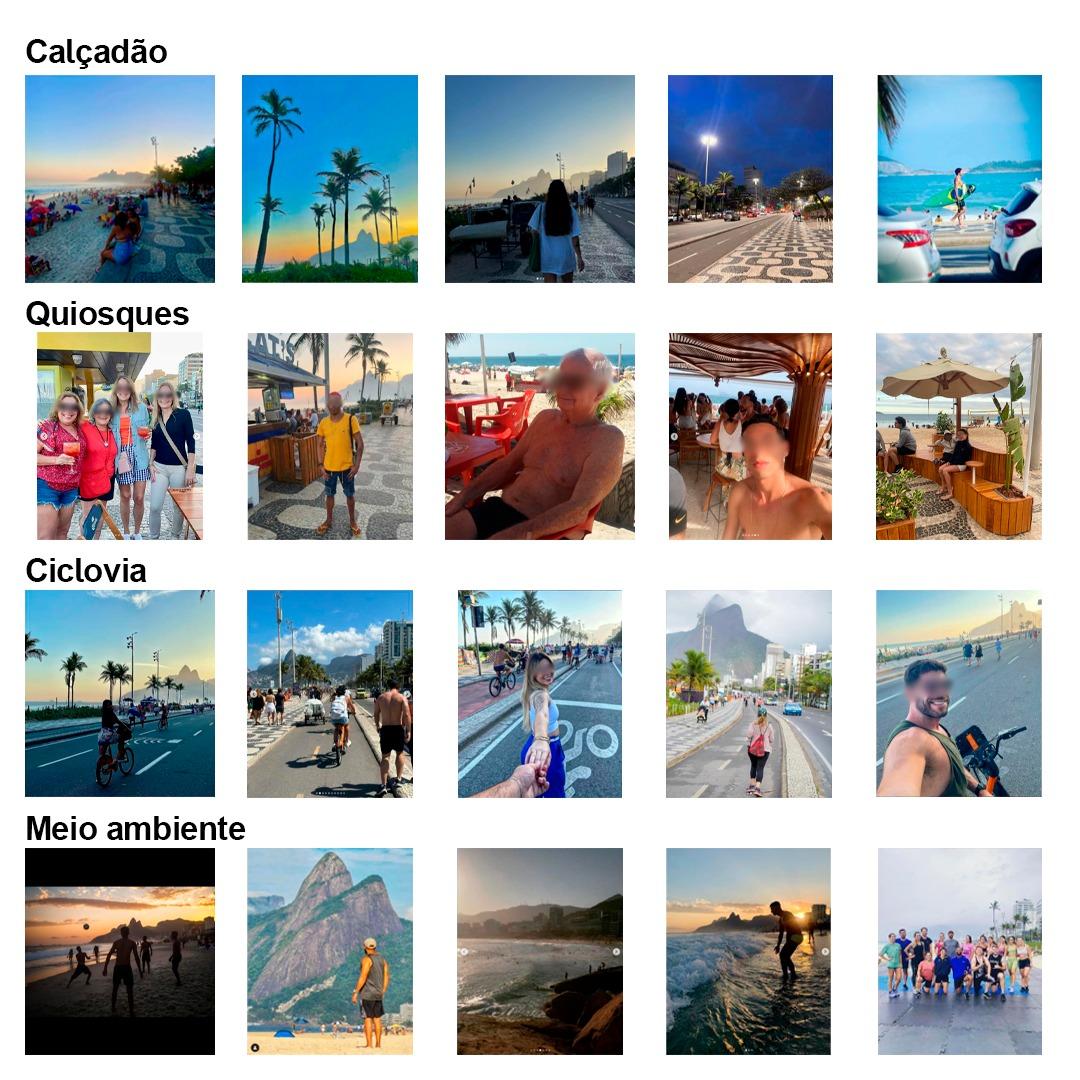

- Instagram – Ipanema and Leblon Segment

Figure 13: Grid of photos tagged in Ipanema and Leblon on Instagram.

Source: Instagram (online)

The images captured in the Arpoador, Ipanema, and Leblon area (Figure 13) prominently emphasize the environmental dimension in their visual composition. The natural landmark of Morro Dois Irmãos, for example, is a recurring focal point across different settings. Social interaction in the area is strongly represented through sports practices, contemplation of the natural landscape, and activities around kiosks. The kiosks themselves are depicted in various formats and urban furniture designs. The bike path offers a continuous sequence of experiences from the neighboring stretch in Copacabana, further reinforced in these posts by the street lane closures on Sundays and holidays for cyclists and pedestrians.

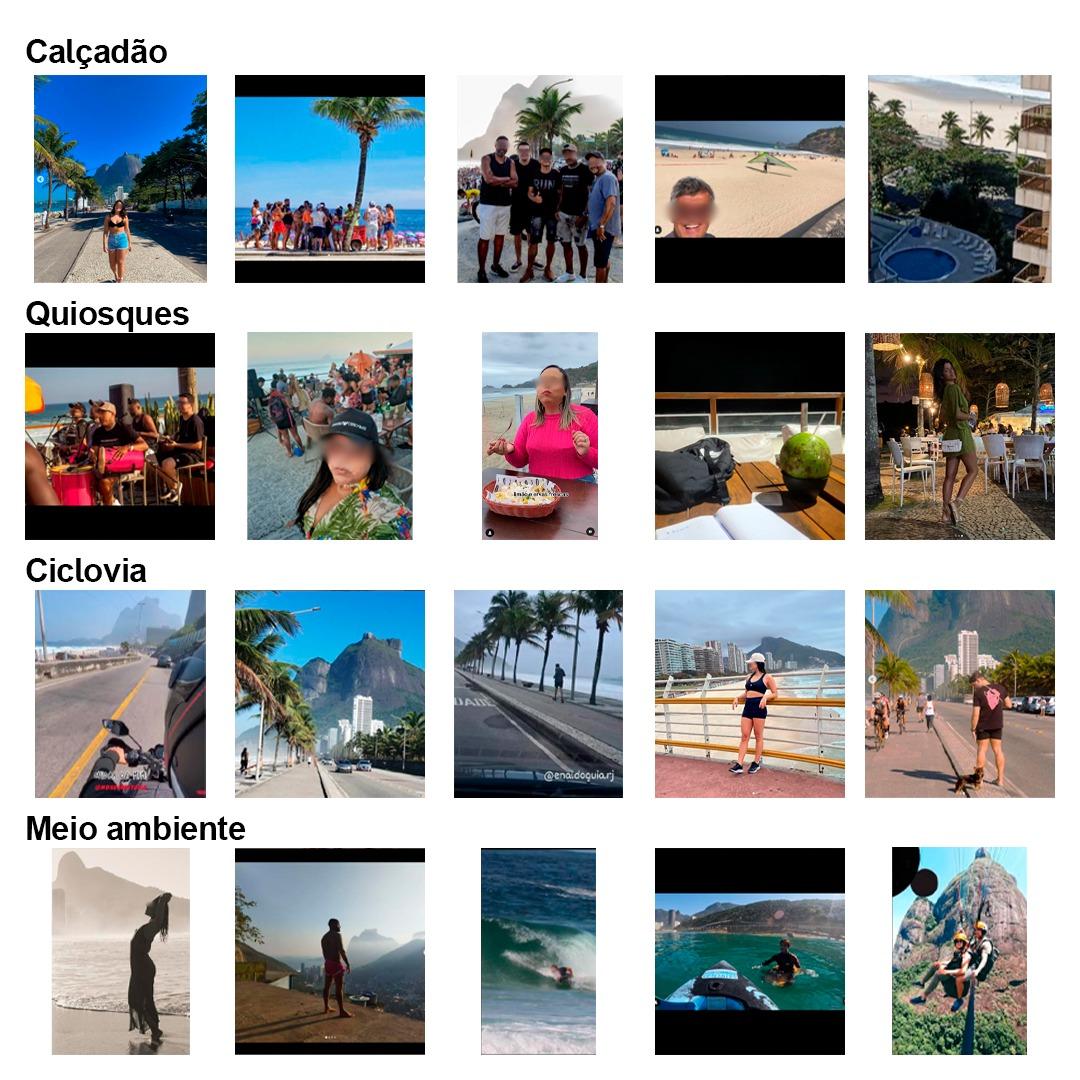

- Instagram – São Conrado Segment

Figure 14: Grid of photos tagged in São Conrado on Instagram.

Source: Instagram (online)

The image set from São Conrado (Figure 14) illustrates a distinct form of connectivity compared to the previous sections. The perspectives captured in the photos emphasize, from various angles, the relationships between inside and outside. Thus, sports practices linked to the environmental dimension, musical events at the kiosks, views of the beach from condominiums and from Rocinha, and the perception of the promenade and bike path from motorcycles and cars together build a visual field lacking a clear integration of all discussed elements. Views of the bike path and promenade also reveal the presence of “blind edges” framing much of the beach’s extension, acting as a barrier to social enjoyment and exchanges with the surrounding areas. However, it is noticeable that there is a maintained level of attractiveness and appropriation by groups who prefer the area.

Transitory Considerations

The dynamism of this network of paths has been stimulated, since its inception, by points of attraction across various qualitative dimensions, including connectivity, commerce for different income and consumption levels, and sociocultural practices of inclusion and exclusion, whether compliant with or transgressive of prevailing governmental norms. These paths are also challenged, in their materiality, by new perceptions, virtual appropriations, approvals and condemnations, under the influence of different times, different rhythms, and different rules that resemble self-management.

The exceptional visibility of one of the three selected segments, the Copacabana shoreline, as well as the myths associated with it, resonate in the observer’s imagination (Bachelard, 1989; Lynch, 1960). Traces of memory, nourished by varied content, influence the choice of practiced routes, shape preconceived notions of hospitality, and outline the perception of the whole based on elements perceived as recurring, focusing on attributes of the image and their associated meanings.

What is understood as the process of imagination formation has undergone, and continues to undergo, significant transformations since the time when Lynch (1960) and Bachelard (1989) published their research and reflections. It has acquired new contributors and contributions, new rhythms of configuration, and a degree of acceleration and transience never experienced before. Records of memory fragments made available to the masses in the virtual space of social media impact the process of imagination formation. They emphasize the component of time while simultaneously minimizing, omitting, and subtracting its duration and meaning (Han, 2021), reducing the relevance of lived experience.

The experiment of observing the virtual representation of the analyzed places suggests surfaces in a process that weaves together notions of a city that produces images and images that produce cities.

The exercise of collecting and observing media published on Instagram, produced in and related to the segments analyzed, enabled a reflection on an imagetic mosaic composed by different authors. By selecting a target for their records, these users express personal desires for representation. However, collectively, they may comprise a shared narrative within a specific window of moments. When analyzing the publications that met the search criteria, it is worth emphasizing the depth of their composition, that is, not only the foreground subject of the photo, but also the contexts and other activities occurring in the background at that moment.

Thus, these landscape snapshots may reveal time fragments in which diverse agents build the collective experience of these places through everyday life. Therefore, such transitory expressions suggest samples of how these lived experiences are distilled into a collective reading of these landscapes.

Nevertheless, even while privileging “Instagrammable” paths, visiting the shoreline segments takes place in the physical space of the boardwalk, which in turn weaves material connections with other uses and mixed functionalities located in the nearby surroundings, such as the shops and hotels along the seafront, as well as in the not-so-near surroundings, like the metro stations serving the neighborhood across the two shoreline stretches, from Leme to Leblon. These lived experiences, although altered in the formation of reference memories and interpenetrated by other layers, still carve out paths.

Public space, as well as the varied forms of social, cultural, and economic appropriation it accommodates, is in constant motion. The greater its attractiveness, the more adaptations it undergoes in response to the customs and desires of the population, and the greater the political, economic, and digital pressures influencing its management.

Undoubtedly, this is the case with the shoreline. The “Rio Orla Project” was a bold intervention. It was well received and embraced by the population.

The bike path, with its physical characteristics (width, location) and operation (signage), remained the same. What changed profoundly were the population’s habits. The global trend of bicycle use had not yet taken hold in the city. It became fashionable right in the heart of the South Zone! This was facilitated by the bike path network offered, supported by the beauty of the landscape it allowed one to contemplate. In Rio, urbanism took the lead. However, the civilizing proposal that accompanied it did not succeed as much as expected.

The Rio Orla Project sought to simplify the operation of kiosks, regulate food stand operations on the sand, and proposed that sports events and concerts take place off the beach. This did not work. The kiosk operators, grouped under a concessionaire, expanded their services, with tables, chairs, music, and lights. Events on the sand grew significantly. Economic pressure, including the demand for work, continues to drive these changes.

References

ABREU, Maurício de. Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Zahar; IPLANRIO, 1987.

BACHELLARD, Gaston. A poética do espaço. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1989.

CARVALHO, T.; PACHECO, F. Cidade, modos de ver e de fazer vitalidade urbana no dia a dia. Revista de Morfologia Urbana, [S. l.], v. 7, n. 1, p. e00062, 2019. DOI: 10.47235/rmu.v7i1.62. Available at: https://revistademorfologiaurbana.org/index.php/rmu/article/view/62. Access in: 26 mar. 2025.

CONZEN, Michael R.G. Alnwick, Northumberland: A study in town-plan analysis. [With plates, plans and a bibliography]. Londres: Institute of British Geographers Publication, 1960.

COPACABANA. In: Wikipédia: a enciclopédia livre. Wikimedia, 2025. Available at: https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copacabana. Access in: 15 april 2025.

HAN, Byung-Chul. Favor fechar os olhos. Petrópolis, RJ: Editora Vozes, 2021.

LAZEBNA, Olena. O humor na perspectiva linguística: o problema da classificação. Araraquara: Revista EntreLínguas, 2022.

LYNCH, Kevin. A imagem da cidade. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1960.

MAGALHÃES, Renata. How to annoy a Carioca. ln: Time Out. The essential guide to Rio de Janeiro. 17 mai. 2024. Available at: https://www.timeout.com/rio-de-janeiro/things-to-do/how-to-annoy-a-carioca. Access in: 15 abr. 2025.

O‘DONNEL, Júlia. A invenção de Copacabana: culturas urbanas e estilos de vida no Rio de Janeiro (1890-1940). Rio de Janeiro: Editora Zahar, 2013.

PEREIRA, Déborah. Funcionamento discursivo dos hastags: um olhar para a #SOMOSTODOS. 2018. Dissertação (Mestrado em Divulgação Científica e Cultural) – Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2018.

REGO, Helena; ANDREATTA, Verena. O Projeto Rio Orla. In: ANDREATTA, V. (org.), Do Rio Orla à Orla Conde. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Rio Books, 2019.

ROSSI, Aldo. A Arquitetura da Cidade. Lisboa, Portugal: Edições Almedina, 2016.

STROZENBERG, Alberto. Relatório técnico sobre o andamento dos trabalhos de construção do Projeto Rio Orla. Rio de Janeiro: IPLANRIO, 1991.

STROZENBERG, Alberto; MICAÊLO, Cristina. Ecos da Polêmica. In: Andreatta, V. (org.), Do Rio Orla à Orla Conde. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Rio Books, 2020.

GEHL, Jan. Cidade para Pessoas. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva, 2013.

TSIOMIS, Yannis,. Matières de ville projet urbain et enseignement. Paris: Éditions de la Villette, 2008.

About the Authors

Thereza Christina Couto Carvalho is a Full Professor in the Graduate Program in Architecture and Urbanism (PPGAU) at UFF. Since 2003, she has coordinated a research group and project on public space and territorial planning (RCORT/UFF). She taught undergraduate and graduate courses at the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of Brasília (UnB) from 1990 to 2006. She served as Director of the Integrated Center for Territorial Planning (CIORD), a partnership between the Federal Government and UnB, from 1995 to 2001. Among the publications and technical outputs she coordinated or co-authored are: "Pequeno Glossário Ilustrado de Urbanismo", Rio Books, 2021; Technical Coordinator of the Master Plan for Municipal Urban Development of Niterói (2019), a partnership between the Niterói City Hall, FGV, and UFF; and the edited volume "Efeitos da Arquitetura: os impactos da urbanização contemporânea no Brasil" (Netto, V.; Saboya, R.; Vargas, J.; Carvalho, T.).

Alberto Strozenberg is a statistician and engineer with a postgraduate degree in operational research from COPPE-UFRJ. A founding professor at IBMEC (1970), he worked at the Rio Metro Company in planning and implementation roles. He served as Technical Director of the Rio de Janeiro Planning Institute (IPLANRIO, now IPP), Presiding Director of the Rio de Janeiro Data and Information Center (CIDE), and Undersecretary of Transport and Planning.

Fábio Carneiro Velasco holds a degree in Architecture and Urbanism from the School of Architecture and Urbanism at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF). He was a scientific initiation scholarship recipient (PIBIC) in the research project "DNA da Paisagem Fluminense – a contribution to the study of public spaces in the formation of the city, with an emphasis on the square as an articulator of centralities", from 2015 to 2017. He is co-author of the book "Pequeno Glossário Ilustrado de Urbanismo", published by Rio Books in 2021.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C.C.C., A.S. and F.C.V.; Methodology, T.C.C.C.; Investigation, T.C.C.C., A.S. and F.C.V.; Resources, T.C.C.C., A.S. and F.C.V.; Writing—original draft, T.C.C.C., A.S. and F.C.V.; Writing—review and editing, T.C.C.C., A.S. and F.C.V.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by resources from: Federal Fluminense University (UFF) and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

About Coleção Estudos Cariocas

Coleção Estudos Cariocas (ISSN 1984-7203) is a publication dedicated to studies and research on the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, affiliated with the Pereira Passos Institute (IPP) of the Rio de Janeiro City Hall.

Its objective is to disseminate technical and scientific production on topics related to the city of Rio de Janeiro, as well as its metropolitan connections and its role in regional, national, and international contexts. The collection is open to all researchers (whether municipal employees or not) and covers a wide range of fields — provided they partially or fully address the spatial scope of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Articles must also align with the Institute’s objectives, which are:

- to promote and coordinate public intervention in the city’s urban space;

- to provide and integrate the activities of the city’s geographic, cartographic, monographic, and statistical information systems;

- to support the establishment of basic guidelines for the city’s socioeconomic development.

Special emphasis will be given to the articulation of the articles with the city's economic development proposal. Thus, it is expected that the multidisciplinary articles submitted to the journal will address the urban development needs of Rio de Janeiro.

[1] The conceptualization of the term ‘genetic capital’ emerges from Thereza Carvalho’s postdoctoral research (2008/9), “O DNA da paisagem - mutações e persistências no capital genético dos espaços públicos”, which had as one of its case studies a section of the city of Lisbon, Portugal. The results of this research shaped a method for reading urban space, addressing the ongoing evolution of the city, at times expanding, at times contracting, at times reinventing itself. The urban fabrics studied by the author always contain morphological elements from previous periods, whose passage of time has become sedimented in street layouts, urban structures, or buildings, and are now integrated into the daily lives of the city's inhabitants. These lived experiences imprint signs, leave traces that are at times juxtaposed, at times overlaid and concealed, sometimes valued and preserved, and sometimes abandoned. Together, they form the “genetic capital of the urban landscape.”