Volume 13 Issue 1 *Corresponding author therezacarvalho@id.uff.br Submitted 19 feb 2025 Accepted 14 april 2025 Published 30 april 2025 Citation FERREIRA, Sarah S. B.. The production of exclusionary urban space and the Right to the City in Complexo da Maré. Coleção Estudos Cariocas, v. 13, n. 1, 2025.

DOI: 10.71256/19847203.13.1.136.2025. The article was originally submitted in PORTUGUESE. Translations into other languages were reviewed and validated by the authors and the editorial team. Nevertheless, for the most accurate representation of the subject matter, readers are encouraged to consult the article in its original language.

| The production of exclusionary urban space and the Right to the City in Complexo da Maré A produção do espaço urbano excludente e o Direito à Cidade no Complexo da Maré La producción del espacio urbano excluyente y el Derecho a la Ciudad en el Complexo da Maré Sarah Silva Batista Ferreira1 1Escola Nacional de Ciências Estatísticas - ENCE/IBGE, R. André Cavalcanti, 106 -Centro, Rio de Janeiro -RJ, 20231-050, ORCID 0009-0006-7504-8465, sferreirarq@gmail.com

AbstractThe formation of the Complexo da Maré is directly tied to an urban spatial production marked by forced removals, gentrification, and exclusionary urban planning. The neighborhood faces multiple challenges, including deteriorating infrastructure, lack of basic sanitation, insecurity, armed conflicts, rising homelessness alongside drug dependency, and numerous other violations of fundamental human rights. The absence of the State and unequal urban policies raises critical questions about the root causes of these conditions and the shaping of this territory, motivating a historical and socio-spatial analysis of Maré and its sixteen favelas. Keywords: favela, socio-spatial analysis, right to the city. ResumoA formação do Complexo da Maré está diretamente ligada a uma produção do espaço urbano marcada por remoções, gentrificação e urbanismo excludente. O bairro enfrenta diversas problemáticas como a precarização da infraestrutura, a falta de saneamento básico, a insegurança, os conflitos armados, o aumento de pessoas em situação de rua aliado à dependência química e várias outras violações de direitos humanos básicos. A ausência do Estado e a desigualdade no tratamento urbano levantam questões sobre as causas dessas condições e a formação desse território, motivando uma análise dos processos históricos e socioespaciais da Maré e suas dezesseis favelas. Palavras-chave: favela, análise socioespacial, direito à cidade. ResumenLa formación del Complexo da Maré está directamente vinculada a una producción del espacio urbano marcada por desalojos, gentrificación y urbanismo excluyente. El barrio enfrenta múltiples problemáticas, como el deterioro de la infraestructura, la falta de saneamiento básico, la inseguridad, los conflictos armados, el aumento de personas en situación de calle junto a la dependencia química, y diversas otras violaciones de derechos humanos fundamentales. La ausencia del Estado y la desigualdad en el tratamiento urbano plantean interrogantes sobre las causas de estas condiciones y la configuración de este territorio, lo que motiva un análisis histórico y socioespacial de Maré y sus dieciséis favelas. Palabras clave: favela, análisis socioespacial, derecho a la ciudad. |

Introduction

The issues encountered throughout the length of one of the city’s most important urban axes, Avenida Brasil, are consequences of a historical context marked by the removal of people from more privileged infrastructure zones to peripheral areas and/or risk-prone zones, distant from this infrastructure. These displacements occurred due to urban interventions, the location of industries (job opportunities) alongside available land, or gentrification. The reasons are diverse, but the consequences are common and often overlapping.

Over the years, this stretch of the avenue has seen the expansion of precarious conditions: the lack of infrastructure and basic sanitation — highlighted recently by the health crisis caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic —; insecurity and armed conflicts stemming from the war-on-drugs policy; the absence of the State; exclusionary urbanism and hostile architecture; the housing deficit; and the growing number of homeless individuals alongside chemical dependency.

Given the investigated scenario, several questions arise: Why does this region not receive the same urban infrastructure treatment as other areas of the city? Why are there so many urban voids along Avenida Brasil alongside so many unhoused people, few public facilities, and limited leisure spaces? Why is this territory so hostile? At the same time, doubts emerged about the formation of this territory and the root causes of its challenges.

In light of these questions, this study aims to identify the current territorial issues, outline the historical context of its occupation, and conduct a socio-spatial analysis of the Maré Complex in the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Methodology

To investigate the scenario of the Maré Complex and identify potential answers to the raised questions, a theoretical discussion of topics essential for understanding the urban context of the studied area was conducted. These included: the Right to the City, a concept introduced by Henri Lefebvre in his manifesto-like book of the same title, which critically addresses class struggles, oppressions against minority groups, and urban life; Non-Places, an anthropological theme introduced by Marc Augé in his book Non-Places, discussing the meaning and perspective of this term in contrast to the urban reality of Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone; and, finally, the phenomenon of Urban Voids, referencing various studies on this subject, which is one of the most recurrent issues in the area.

Next, the urbanization of Rio de Janeiro’s city and favelas was analyzed to identify the socio-spatial dynamics that constitute their urban formation and how these processes contextualize the history of the Maré Complex.

Lastly, a territorial mapping of the Maré neighborhood was carried out using data collected from public institutions such as the Instituto Municipal de Urbanismo Pereira Passos (IPP), the Secretaria Municipal de Urbanismo (SMU), and the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE); from academic collective projects in partnership with other organizations; and from non-governmental organizations with significant initiatives in the territory, including Redes da Maré, Data_labe, and the Centro de Estudos e Ações Solidárias da Maré (CEASM).

Theoretical Discussion

- What is the Right to the City?

This phrase was coined by French philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre in his book The Right to the City (2008), a work that interprets the events of its time, marked by youth movements for civil rights, sexual liberation, and opposition to conservatism.

The author introduces two terms for debate: use value and exchange value, which respectively signify “[...] the city and urban life, urban time” and “[...] spaces bought and sold, the consumption of products, goods, places, and signs” (Lefebvre, 2008, p. 35). In other words, the city’s use value is how individuals relate to urban daily life, while the exchange value encompasses all capital-driven relationships tied to it. For example, visiting a park on a sunny Sunday has use value, whereas the transportation taken to reach it and the meal consumed there have exchange value.

According to Lefebvre (2008), oppressions against certain social segments are inherent to the current urbanization model. Thus, urban segregation is analyzed through three perspectives: ecological (encompassing favelas and peripheries), formal (incorporating the deterioration of the city’s meanings), and sociological (involving ethnicities, cultures, lifestyles, etc.).

Ultimately, what is the right to the city? It is, above all, a collective right that transcends demands for urban resources like infrastructure or housing. As Harvey (2003, p. 74) states, “[...] it is the right to change ourselves by changing the city.” Just as social struggles evolve, the idea of the city is in constant transformation, requiring its reclamation as a common good and the rejection of its treatment as a commodity.

The central question is: Why demand the right to the city in vulnerable territories? Historically, informal settlements and favelas exist on the margins of the city and, consequently, of territorial discussions and decisions.

The fragmentation of dominant classes is rooted in the social organization of territory, creating urban areas as distinct environments (neighborhoods, communities) for social interactions where individuals develop their values, expectations, and consumption habits. The impacts of this include blocking the formation of collective class identities and the capacity for collective action in market and political spheres (Ribeiro, 2018, p. 257-258).

i.e., this segregation is not only territorial but also social and political, hindering favela residents’ participation in urban policies. Villaça (2012) introduces the concept of location rent to explain urban segregation. The author refutes the notion that the wealthy inhabit city centers while the poor occupy peripheral regions, arguing instead that the wealthy occupy areas with greater infrastructure investments, proximity to jobs, high-income rates, development, and even “desirable” neighborhoods — where distance from favelas and peripheries increases location value. Certain patterns emerge, often “camouflaging” inequality.

The right to the city is a collective right, and there are many ways to claim it, primarily through participation in urban decision-making and all aspects of city life. The greatest challenge for contemporary urban public policies is to engage with the population, including those living in these territories in democratic discussion spaces. However, popular participation is often neglected, resulting in exclusionary policies that reproduce social inequalities.

- The Non-Place?

The term was introduced by Marc Augé (2017), referring to a space with which humans do not establish any meaningful connection — a space they do not appropriate. A non-place is an area where no references are built, where life is not lived, and where individuals remain anonymous and solitary. Examples include supermarkets, transportation hubs, sidewalks, and stations.

However, the concept also carries a subjective dimension, where individuals may perceive a space as a non-place in their own way. Understanding this idea is crucial for grasping the future of cities, as the human tendency to avoid forming attachments leads to the erosion of meaning in places (Augé, 2017).

Hertzberger (2015, p. 12) argues that “[...] in an absolute sense, we can say: a public space is one accessible to everyone at any time, with its maintenance collectively assumed.” This implies that public spaces are prone to collective neglect, as a space belonging to everyone simultaneously belongs to no one. Thus, public spaces risk becoming non-places due to abandonment or underutilization.

The presence of a major expressway cutting through the Maré territory has turned certain areas into non-places. These are typically transitional spaces, such as the undersides of viaducts. This configuration has allowed for the formation of urban voids that give way to a cracolândia[1] (open-air drug market) located between the descent of the Brigadeiro Trompowski Avenue viaduct and the Avenida Brasil’s Passarela 9. It is a region that “belongs to no one,” occupied by dehumanized individuals.

The result is that almost no interventions are implemented to address this issue. Instead, public authorities employ misguided tools aimed at displacing these groups, such as filling viaduct undersides with sharp rocks to deter occupation. This is a common sight in global metropolises, a phenomenon termed Hostile Architecture[2].

Recently, an incident in São Paulo drew national media attention: Father Júlio Lancellotti — a figure known for supporting homeless populations — was filmed removing rocks placed by the City Hall under the Dom Luciano Mendes de Almeida Viaduct to prevent homeless individuals from occupying the area. Following public outcry, the City Hall removed the rocks. This event also led to *Decree 11.819/2023*, which regulates a law prohibiting such initiatives.

- Urban Voids

Urban voids are spaces in the city that do not fulfill their social function, such as vacant lots, abandoned or deteriorated buildings, and unused structures. Many of these places, whether publicly or privately owned, have unpaid taxes and/or lack any construction or project aimed at giving them a functional use.

The Brazilian Federal Constitution (1988) provides for the social function of property, which means that property must be used in accordance with the social objectives of a given city. This principle places limits on property rights to ensure that ownership does not harm the collective good. Whether urban or rural, property must also serve the public interest beyond the private interests of its owner. For urban property, the criteria for fulfilling this social function are defined in Article 182. In addition, it must comply with the requirements of the municipality’s Master Plan[3] (Plano Diretor).

Several measures can be taken to prevent the emergence of urban voids and to encourage owners of underutilized or abandoned properties to repurpose them. These include: compulsory subdivision, which involves notifying the owner and requiring the property to be subdivided, developed, or used in accordance with local urban planning regulations (with the conditions for application defined by municipal law); progressive property taxation (IPTU), which imposes increasing tax rates over time to pressure owners to put unused property to productive use and penalize those who fail to meet its social function; and finally, expropriation, in which ownership is transferred, either from the private sector to the public sector or from one government level to another, with fair and prior compensation[4].

Along the stretch of Avenida Brasil that passes through the Maré neighborhood, numerous properties can be classified as urban voids. Some have been abandoned for years, others are underused, and many have no designated use. As part of this study, a photographic survey was conducted following an on-site visit, and Google Maps was used to geolocate the identified voids. This mapping exercise not only substantiated the present research but also informed the selected area for the proposed intervention.

Various types of underutilized urban developments were found, such as industrial warehouses located next to Clotilde Guimarães Municipal School. These structures occupy a large plot of land, resulting in inactive street façades along Avenida Brasil, from the return road to Ilha do Governador up to the school's access point. Another example is the Restaurante Popular João Goulart, strategically located across from the main entrance to the Parque Maré favela. While this spot is critical for the homeless population and surrounded by varied commerce, the building is in disrepair and only its ground floor is currently used for the restaurant.

Throughout the Maré territory, dozens of similar developments were identified, forming a repetitive pattern. Some of these spaces have been occupied by people experiencing homelessness, while others have been irregularly converted into commercial establishments.

Contextualization

- Notes on the Urbanization of Rio de Janeiro

To understand the socio-spatial formation dynamics and socio-spatial segregation phenomena, this analysis will focus on three critical periods in Rio de Janeiro’s history: the 1930s–1940s, the 1950s to the Military Dictatorship era, and the 1980s to the early 21st century.

During the 20th century, Rio de Janeiro underwent four major urban plans crucial to its spatial configuration: the Plano Agache (1930), Doxíadis (1965), Pub-Rio (1977), and the Plano Diretor Decenal (1992). Torres (2018, p. 289) notes that “[...] the urban morphology we know today results from disputes and conflicts in a long historical process of unjust spatial production dominated by social inequalities.”

Before the 19th century, the city was heterogeneous and dense. Given the context of slavery and limited transportation, social segregation was based on appearance and ownership rather than location. According to Abreu (2006), the separation of land uses and social classes in Rio began with the introduction of mass transit. Since then, the city began to divide into three main areas: the central core, with non-residential activities and tenements; the South Zone, served by streetcars and home to the upper-class residences; and the North Zone, with working-class suburbs, occupied by industries and served by trains.

During the Vargas era, Rio was the Federal District, grappling with the effects of the 1929 Crash and Alfred Agache’s urban remodeling plan — though never officially adopted, it heavily influenced urban legislation. Henrique Dodsworth’s Plano da Cidade included road projects connecting downtown to other areas, accelerating suburban occupation as urban interventions and industrialization drove migration from the Central and South Zones to the North and West Zones.

The 1940s saw a new urbanization phase with the construction of major avenues: Avenida Presidente Vargas, a monumental route that required massive historical demolitions, and Avenida Brasil, a Rio-Petrópolis highway alternative along Guanabara Bay’s sparse coastline.

After Avenida Brasil’s 1946 inauguration, factories proliferated, shaping what Torres (2018) calls the “automobile suburb.” The area, already occupied, densified further due to industrialization and job opportunities, as workers prioritized proximity between homes and workplaces. This explains why industrial zones between railways and the avenue were heavily settled.

Housing policies also contributed to densification, such as the Parques Proletários (the first government policy for favelas). Initial actions relocated South Zone favela residents to these parks, which later spawned new favelas across Rio (Rodrigues, 2020).

In the 1950s, rural migration spurred occupation in peripheries and favelas. Urban policies increasingly prioritized Center-South growth, leading to intensified removals of settlements in these areas. The Lacerda government, for instance, built housing complexes like Vila Kennedy and Nova Holanda to accommodate displaced favela residents.

In the 1960s, Rio lost its capital status to Brasília but remained a metropolis undergoing renewal, aligned with Brazil’s highway-centric growth until the 1970s “lost decade.” By the 1980s, the city shifted toward decay and inequality, with public investments favoring wealthy areas and cars over suburbs and mass transit.

For Ribeiro (2018, p. 265), 1980–2010 consolidated three dynamics in Rio’s metropolitan territorial organization: “self-segregation of upper classes” in well-serviced areas; “peripheralization of popular classes” in zones like the West and Baixada Fluminense; and “[...] infiltration of metropolitan core and immediate periphery by these layers,” known as “favelization.”

A complex residential segregation pattern operates at two scales: macroscopically, the metropolitan periphery — despite social diversification — remains socially distant from the core; microscopically, favelas (regardless of location) lack significant social diversity (Ribeiro, 2018).

Another key observation is the favela-territory dichotomy. Socioeconomic proximity between favelas and peripheries increases with geographical closeness, as seen in Baixada Fluminense. Conversely, favelas near the core (e.g., South Zone) exhibit greater socioeconomic distance from surrounding areas (Ribeiro, 2018).

- Notes on Favela Urbanization

The city of Rio de Janeiro displays a spatial structure that reflects the systems of power distribution in the country and the reproduction of capital. The state reinforces territorial segregation through selective investment, favoring certain areas to the detriment of others. This perpetuates a vicious cycle: the wealthy concentrate in specific areas while the poor are pushed out through mechanisms such as real estate speculation, elitist legislation, urban renewal (which can lead to gentrification), rising taxes, segregating housing policies, and the eradication of favelas in these zones (Abreu, 2006).

The state of Rio de Janeiro has 12.06% of its households located in substandard settlements. In the capital, there are 576,772 households across approximately 813 favelas, corresponding to 19.75% of the city’s total households (IBGE, 2022). As previously discussed, this reality stems from the historical urban configuration of Rio de Janeiro and the socio-spatial processes it has produced. Modernization and industrialization were the main drivers of unregulated urban growth, and their legacy is reflected in the high concentration of favelas across the city.

It is important to note that public authorities themselves have played a role in the formation of favelas. The first governmental policy for the city’s favelas was the establishment of the Commission for Favelas and Proletarian Parks in 1941, led by the Retirement and Pension Institutes (IAPs). This initiative began with the relocation of favelas from the Lagoa area to Proletarian Park 1, created in Gávea, marking the start of an era of construction and attempts to “urbanize” favelas. These parks served as temporary housing for residents displaced by removals. However, studies show that some favelas in the Manguinhos Complex were also formed through these removals. Similarly, some housing complexes built by the IAPs were constructed on sites of pre-existing favelas (Ribeiro, 2018).

Starting in the 1950s, the growth of favelas became increasingly linked to rural exodus. Yet, urban policy remained essentially unchanged, structured around three main pillars: selective removal of certain favelas, limited improvements in others, and the selection of residents deemed “most suitable” to receive IAP benefits. In 1953, however, Mayor Dulcídio Cardoso took a pivotal step by suspending removals until adequate resettlement locations were available, creating favorable conditions for favela residents to mobilize. This led to 1954 becoming a landmark year with the approval of numerous land expropriation projects. The second half of the decade was marked by ambivalent policies—on the one hand, the creation of parks for displaced residents, and on the other, agreements that allowed for a significant increase in informal occupations (Ribeiro, 2018).

In the 1960s, under Governor Carlos Lacerda, removals began to focus on relocating residents to public housing complexes. The first of these were Vila Aliança and Vila Kennedy in the West Zone. Temporary housing complexes were also built, including Nova Holanda in the Maré Complex. By the end of the decade, the real estate assets of the former IAPs were transferred to the Social Interest Housing Coordination (Chisam), intended to promote new public housing projects. However, many of these lands were already occupied by favelas. Between 1962 and 1974, Chisam was responsible for the removal of 80 favelas—a policy of eradication that, paradoxically, did not prevent the continued growth of favelas (Mendes, 2006).

As public housing projects declined, a major issue emerged: most favela residents could not afford to remain in their new housing. As a result, units began to change hands and many residents returned to favelas. This dynamic underscored that favelas remained the most economically viable housing option for this population (Valladares, 1978 apud Mendes, 2006). According to Mendes (2006), despite the absence of public policies directly aimed at favelas, this period marked the rise of awareness regarding the need to urbanize these areas.

A favela is not merely the result of a housing crisis within the context of rapid urbanization. It is not only a matter of housing shortage or the inability of the public and private housing markets to meet a growing demand. A favela is primarily the product of labor exploitation within a stratified society where inequalities tend to persist, and capital accumulation is ever-increasing. It also results from a situation in which land use is increasingly driven by property value, and control of urban space is exercised by or in the interest of dominant social groups (Valladares, 1978 apud Mendes, 2006, p. 93).

In 1979, the federal government launched the PROMORAR program with the goal of eradicating favelas through urbanization, sanitation, and the construction of adequate housing, also including land tenure regularization. Unlike the earlier removal-based policies, this program aimed to ensure the permanence of favela residents. This marked the inclusion of favelas in the broader urban agenda and planning efforts.

That same year saw the creation of the Projeto Rio, aimed at recovering flooded areas in Guanabara Bay. Although favela issues were not the primary focus—since the goal was to address environmental concerns—the project sought to improve housing and employment conditions in those areas. It was part of the Pub-Rio Plan, which aimed at municipal urban planning to address the city's territorial imbalances. Within the project, sanitation was seen as the greatest housing issue in favelas. It was believed that intervening in these areas would allow the government to implement a broader citywide sanitation plan. Another important initiative was the Urban Recovery Project of Projeto Rio, which addressed zoning for residential use, the need for reurbanization, and improvements across all favela areas (Mendes, 2006).

In 1981, the Projeto Mutirão was launched using a methodology developed by the Municipal Secretariat for Social Development (SMDS). The project aimed to serve fifteen favelas through infrastructure works such as road access, paving, slope containment, water supply, and sewage treatment. Initially, SMDS provided technical support and construction materials, while the community carried out the work. After 1983, the Secretariat became responsible only for sewage installation, and the construction work shifted to a mix of paid and volunteer labor. By 1988, the project had reached 127 favelas (Fontes; Coelho, 1989 apud Mendes, 2006).

During Leonel Brizola’s administration, a social agenda was developed specifically for favelas, focusing on urbanization. Key actions included: CEDAE’s Favela Program (PROFACE); waste collection initiatives with the Municipal Urban Cleaning Company (Comlurb); public lighting programs with the Municipal Energy Company; and the "Each Family, One Plot" Program for land regularization, in partnership with the State Secretariat for Labor and Housing.

On the other hand, this decade also saw the consolidation of a persistent issue: the territorial control of favelas by drug trafficking (Souza, 2000 apud Mendes, 2006). This led to greater detachment between urban policies and favelas, weakened residents’ associations, and further isolated these territories from the rest of the city — reinforcing the “favela vs. neighborhood” duality.

The early 1990s brought the Rio de Janeiro City Master Plan (1992) and the launch of the Favela-Bairro Program (1993). The Master Plan outlined guidelines for favela urbanization involving infrastructure, housing, land tenure regularization, and integration. It designated all settlement and favela areas as Special Social Interest Areas (AEIS), to be prioritized for urbanization (Mendes, 2006). The Favela-Bairro Program, initiated during César Maia’s first term and promoted by the Municipal Housing Secretariat (SMH) with support from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), aimed to build or enhance infrastructure in medium-sized, consolidated favelas. In its initial phase (1994–2000), it reached 54 favelas, and during the second phase (2000–2008), it benefited 143[5] (De Duren; Osorio, 2020).

In 2007, the federal government launched the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC), which aimed to promote large-scale infrastructure investments nationwide. According to Ximenes and Jaenisch (2019, p. 14), “it was a key component of the economic development policies implemented [...] and quickly took on a large scope in terms of reach and resources invested.” Within PAC-Favelas, the program branch targeting favela urbanization, Rio de Janeiro received the largest share of investments, with 33 projects carried out in 30 favelas or complexes[6], representing 70% of the state’s total allocation.

Rio also received housing investments through the Minha Casa Minha Vida Program (PMCMV), in conjunction with PAC-Favelas. However, some projects were overly grandiose, and basic infrastructure was not prioritized. A prime example is the Providência Cable Car, inaugurated in 2014 to improve favela accessibility, but which ceased operations in 2016.

Starting in 2009, as Rio prepared to host major international sporting events—the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics—investments surged, and the Porto Maravilha Urban Operation began. That same year, under Mayor Eduardo Paes, the Morar Carioca program was reinstated, with the goal of urbanizing all of the city’s favelas by 2020. However, this occurred amid worsening social inequality and rising urban land prices due to major transformations in the city. Many residents were removed from Olympic development zones and precarious housing under the PMCMV.

In its initial phase (2010), Morar Carioca aimed to complete projects from previous administrations. In the second phase, the plan was to hold a competition in partnership with the Brazilian Institute of Architects (IAB) to hire firms to work in clusters of favelas — prioritizing areas near Olympic projects. However, by the end of Paes’ term, phase two remained unfinished: few new works had begun, most ongoing projects were still from phase one, and timelines were not met.

In 2017, under Mayor Marcelo Crivella, the city launched Goal 73 – to serve 21 favelas. The Favela-Bairro name was revived for projects left incomplete from Morar Carioca and other earlier programs. However, according to the Municipal Audit Court (TCM), only 15 of those favelas saw their works completed (Magalhães, 2019).

Currently, after the pandemic, favela urbanization policies are progressing slowly. In Eduardo Paes’ third term, new initiatives emerged, such as Social Territories in partnership with UN-Habitat and the continuation of Morar Carioca. With a focus on social interest housing, more than 700 residential units were delivered in 2024 in the Aço favela in Santa Cruz.

What has been observed in favela urbanization policies since the last century is their discontinuity with each new administration. Structural characteristics persist in urban policies: their piecemeal nature, frequent terminological shifts, the lack of meaningful public participation, and the absence of integrated planning. Although some interventions have led to improvements in specific favelas, it is essential to recognize that these territories possess complex socio-territorial dynamics that must be understood prior to any urbanization effort.

Territory

- Formation of the Maré Complex

Between the 17th and 18th centuries, the area was part of the Inhaúma Cove, which belonged to the Engenho de Pedra plantation, in what was then the Parish of Inhaúma. Over the years, the land underwent subdivision processes due to urban expansion and eventually gave rise to some neighborhoods in the Leopoldina region. According to Silva (2006), the region had two important ports for the outflow of plantation production: Inhaúma and Maria Angu. The mangrove area of the cove was considered unattractive for any kind of development and held little commercial value, which is why its few residents were mostly fishermen and some people displaced by removals taking place in the city center.

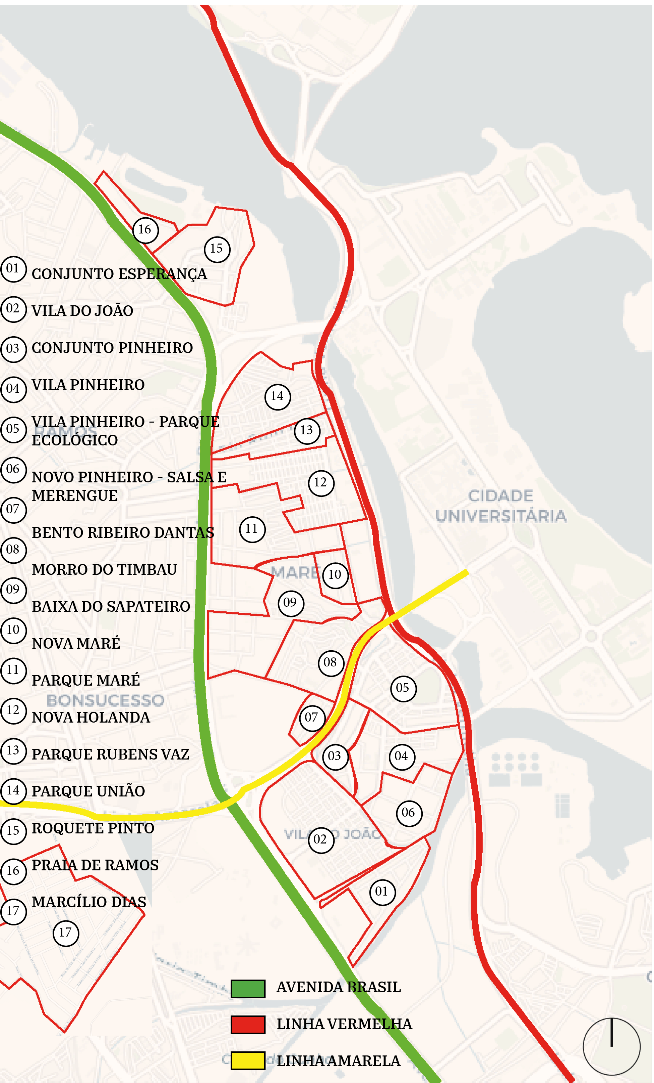

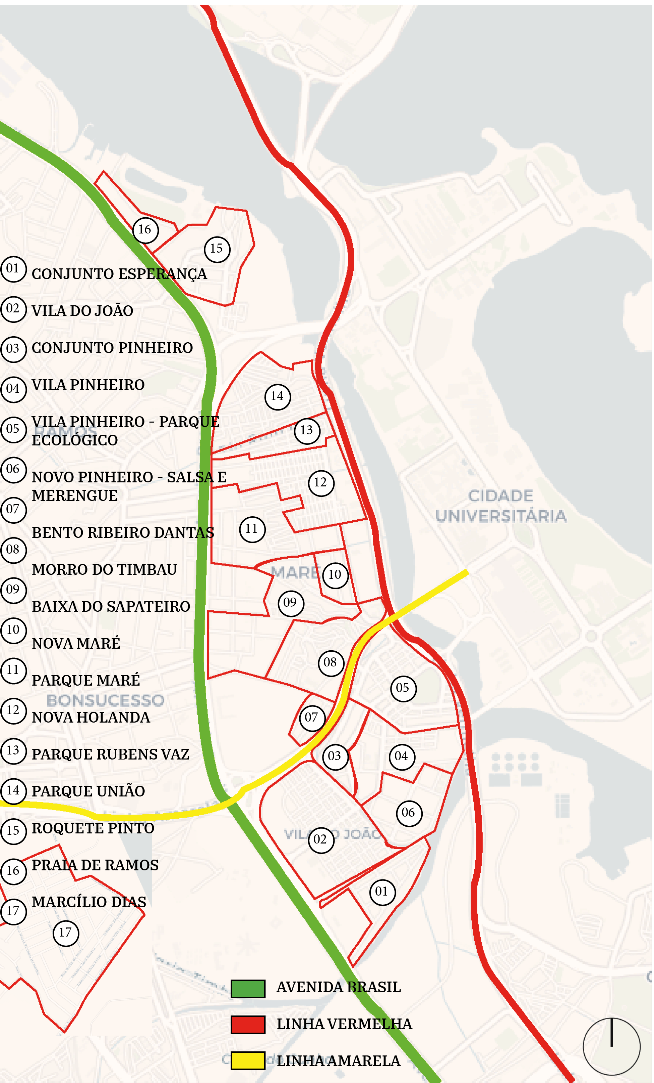

Figure 1: Boundaries of the favelas in the Maré neighborhood – Not to scale.

Source: Prepared by the author based on Redes da Maré, 2019.

The oldest community in Maré is Morro do Timbau (from the Tupi expression thybau, meaning “between waters”), located in the southern part of the region, and was the only solid land among the mangroves of Inhaúma Cove. According to researchers from the Maré Development Networks organization (2013), there were two settlement cores in the area: the Praia de Inhaúma core, linked to the occupation process of the former Parish of Inhaúma by fishermen; and the Morro do Timbau core, a higher and drier area associated with the process of marginalization and precarious living conditions of the city’s poor population. They state that the first residents of the Praia core were workers at a quarry established in the early 20th century due to major city reforms. As for the Morro core, a woman named Orosina Vieira is said to have settled in the area in the 1940s after visiting the region with her husband, as she saw it as a way out of the precarious conditions of her rented housing in the city center.

During the 1930 Revolution, Rio de Janeiro was undergoing industrialization, and the population growth in Maré began as part of an industrial project. Due to high land costs in central areas and legislative restrictions, there was a strong trend of decentralizing industrial activities. Thus, large companies moved to the railway suburbs, attracting migrant populations. Even at that time, the Vargas government already had plans to transform the area into an industrial belt. During this period, land values rose in the Leopoldina region, and the poorest were left with no option but to move toward the cove, occupying flood-prone areas under precarious conditions.

The occupation of Maré consolidated in the 1940s, when the federal government ordered the construction of the Rio-Petrópolis Highway Variant (now Brazil Avenue) – landfills were carried out in the cove and access roads were built – providing a way to settle the area. Another decisive factor for the growing occupation was the creation of new jobs: both the construction works and the establishment of companies in the industrial grid attracted many workers who settled nearby. Over the years, new favelas emerged in the territory, such as Baixa do Sapateiro in 1947 and Marcílio Dias the following year. While various sanitation and removal policies were being implemented throughout the city, Maré continued to expand.

In the 1950s, rural exodus significantly intensified the occupation. Yet the motivations for settling the cove largely remained related to recent construction works in the city. The building of the University City[7] played an important role in this occupation process, as many workers from the construction projects and residents of the annexed islands moved to the region. Additionally, the expansion of the South Zone, driven by public removal policies, brought many of these people to the area. At that time, three more favelas were created: Parque Maré (1953), Parque Rubens Vaz (1954), and Parque Roquete Pinto (1955).

[…] one of the degrading impacts of demographic growth in the region was waste production. […] since the population density in Praia de Inhaúma occurred, as we have seen, in a context of worsening living conditions for the poor who were being pushed to the outskirts. This logically implied the absence of the most essential public services, such as water, electricity, sewage, and garbage collection. (Redes da Maré, 2013, pp. 42–43)

From the 1960s onward, a period marked by removal policies, the residents of Praia de Inhaúma found themselves without alternatives[8]: those with some financial means moved to housing complexes built in the railway suburbs, while those who could not afford it were relocated to more distant complexes, such as those in the West Zone. The housing policy of that time was characterized by violence and disregard for the future of these people. They were sent far from their workplaces and support networks to housing that lacked basic infrastructure and access to public services.

It was in this context that Nova Holanda was created, the first housing complex in Maré and one of the three Provisional Housing Centers (CHP), intended to accommodate people removed from the South and North Zones. In the same year, the COHAB Praia de Ramos was also implemented. Developed through public policies, they marked a new phase in the occupation of the favela complex through public intervention.

Twenty years later, in 1980, the Projeto Rio was launched, playing an important role in the urbanization of Maré. Another landfill was created in the area closest to the Bay, Baixa do Sapateiro. Residents of the stilt houses were relocated to new housing complexes: Conjunto Esperança and Vila do João in 1982, Vila dos Pinheiros in 1983, and finally the Pinheiros Housing Complex in 1989. During this period, policies became more difficult to implement due to the strengthening and expansion of the parallel power structure in favela territories, which consequently intensified police interventions and violence.

“As in other favelas, there is a set of negative representations associated with Maré and its residents, created by external agents and which strongly affect the daily lives of its inhabitants – being identified as a favela resident generally means carrying a heavy burden of stereotypes and prejudice.” (Redes da Maré, 2012, p. 25)

At the end of the century, the Morar Sem Risco Program was launched, aimed at favelas in risk areas that could not be urbanized by the Favela-Bairro program. It was responsible for the last housing policies in Maré, creating the Bento Ribeiro Dantas Complex (1992), characterized by modular construction using structural red ceramic bricks. It also relocated the last families living in stilt houses in Praia de Ramos and Parque Roquete Pinto to the newly created Nova Maré (1996).

Meanwhile, after years of struggle, Maré was officially recognized as a neighborhood of the 30th Administrative Region by Law No. 2,119, dated January 19, 1994. This formal recognition represented a political and symbolic milestone for the territory, as it established Maré as a legitimate urban space with its own history, social and cultural dynamics, strengthening the sense of belonging and repositioning it in the urban imagination as an integral part of the city. This achievement contrasts with the removal policies of previous decades, marking a shift in the recognition of favelas as structural components of the metropolis.

In the same year, another public intervention played a major role in shaping the region: the implementation of the Red Line expressway. Designed to connect Galeão Airport to the city center, it skirts the favela complex but has only one access point near Vila dos Pinheiros. A few years later, the Yellow Line was built, an important road connecting Barra da Tijuca to several suburban neighborhoods and ending at Fundão Island. As it crosses through Maré’s territory, it is more permeable, featuring two pedestrian overpasses that connect the communities on either side of the road.

Finally, in 2000, the Novo Pinheiros Complex was founded, popularly known as Salsa e Merengue, the last favela to become part of the Maré Complex. According to Redes da Maré (2013, p. 26), “[...] Maré was the result of the phenomenon of marginalization and precariousness [...], yet it is equally true that Maré is also the result of the brave and persistent struggle of its residents, [...]”. The neighborhood endured despite removals, interventions, and state repression policies, which also contributed to the territory’s expansion.

From this point onward, the analysis was based on different sources: local surveys such as the Maré Census conducted in 2019 by the Redes da Maré organization; official statistics, including the 2022 Demographic Census, which provides indicators for favelas and urban communities[9] as well as neighborhood-level data; and technical indicators from institutions such as the João Pinheiro Foundation (FJP), the Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA), municipal secretariats, and other bodies. This information makes it possible to understand both the territorial characteristics and the living conditions and needs of the population.

- Instagram – Ipanema and Leblon Segment

According to the Maré Census (Redes da Maré, 2019), 139,073 inhabitants live in the territory. This figure closely aligns with the 2022 Census estimate, which projects 124,832 people living in Maré. This places the neighborhood among the most populous in the city, with a population density of over 29,000 inhabitants per square kilometer (IBGE, 2022).

Table 1: Households, residents, and average residents per household.

Territorial Unit | Households | Population | Avg. residents per household |

Houses | % | Residents | % |

Maré | 47758 | 100,00 | 139073 | 100,00 | 2,91 |

Parque União | 7600 | 15,90 | 20567 | 14,80 | 2,91 |

Vila dos Pinheiros | 5067 | 10,60 | 15600 | 11,20 | 3,08 |

Nova Holanda | 4601 | 9,60 | 13799 | 9,90 | 3,00 |

Parque Maré | 4552 | 9,50 | 13164 | 9,50 | 2,89 |

Vila do João | 4453 | 9,30 | 13046 | 9,40 | 2,93 |

Baixa do Sapateiro | 3287 | 6,90 | 9329 | 6,70 | 2,84 |

Parque Roquete Pinto | 2867 | 6,00 | 8132 | 5,80 | 2,84 |

Parque Rubens Vaz | 2395 | 5,00 | 6222 | 4,50 | 2,84 |

Morro do Timbau | 2359 | 4,90 | 6709 | 4,80 | 2,84 |

Marcílio Dias | 2248 | 4,70 | 6342 | 4,60 | 2,82 |

Novo Pinheiros (Salsa e Merengue) | 2163 | 4,50 | 6791 | 4,90 | 3,14 |

Conjunto Esperança | 1870 | 3,90 | 5356 | 3,90 | 2,86 |

Conjunto Habitacional do Pinheiros | 1342 | 2,80 | 4028 | 2,90 | 3,00 |

Praia de Ramos | 1064 | 2,20 | 3221 | 2,30 | 3,03 |

Nova Maré | 944 | 2,00 | 3215 | 2,30 | 3,41 |

Conj. Bento Ribeiro Dantas | 943 | 2,00 | 3553 | 2,60 | 3,77 |

Source: Redes da Maré, 2019.

Drawing from the Maré Census (2019), it is clear that the favela with the largest population is Parque União, which accounts for 14.80% of the total population of the neighborhood (Table 1). Parque União is among the oldest communities in Maré and was the last one to originate from spontaneous settlement.

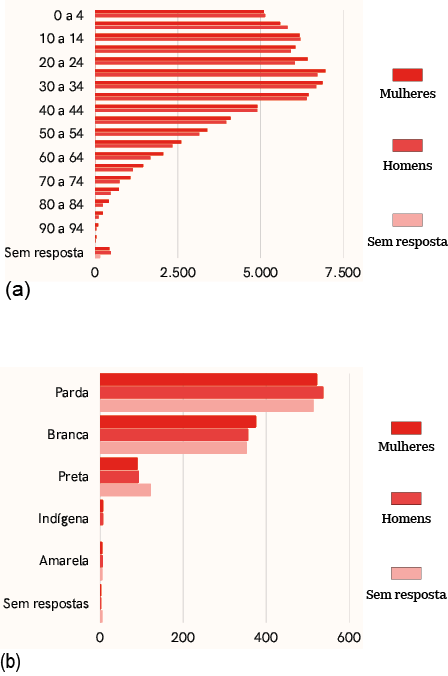

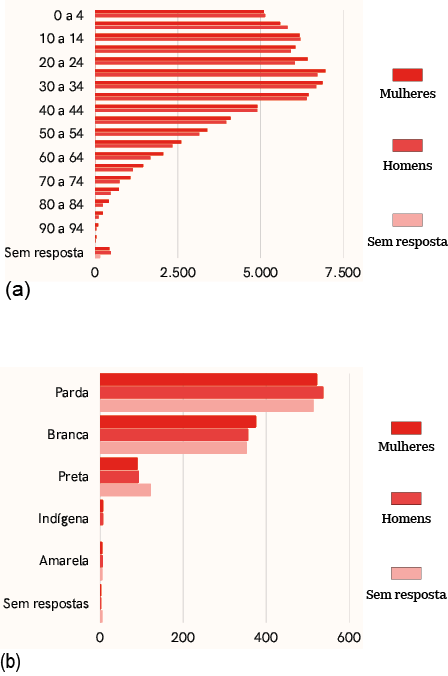

Another important point to highlight is that the majority of the population is young, female, and brown-skinned (parda) (Figure 2). These data reinforce the socio-spatial complexity of Maré, where internal inequalities and social markers (age, gender, and race) continue to shape unequal living conditions.

Figure 2: Charts (a) Residents of Maré by sex and age group; (b) Residents of Maré by race/color and sex.

Source: Prepared by the author based on Redes da Maré, 2019.

- Mobility

What can be observed in the territory is a lack of public transportation within its urban fabric. While there are numerous bus lines available, they operate exclusively on the main highways, such as Avenida Brasil and Linha Amarela. There are no municipal bus routes circulating within Maré itself.

Another alternative is the newly inaugurated Transbrasil BRT (Bus Rapid Transit) line. Under construction since 2014 and completed in 2024, it connects the Deodoro neighborhood to the city’s central region. The line spans approximately 39 km and features five stations within the vicinity of Maré: Fiocruz, Hospital de Bonsucesso (CPOR), Baixa do Sapateiro, Rubens Vaz, and Praia de Ramos. Additionally, the Transcarioca BRT line has one station near Parque União.

Despite the presence of some bicycle paths within the Maré Complex, the current infrastructure is insufficient to meet the mobility demands of such a vast territory. Given the historical lack of efficient public transportation in the region, the high population density, and the long distances between the edges of the complex, the bicycle emerges as a potentially strategic—yet underutilized—solution due to structural limitations.

Data from the 1st Maré Mobility Sample (Redes da Maré, 2015) reveal contradictions in residents’ perceptions: 35% see potential for improved speed in internal travel, while 42% express concerns over safety. The current network is also criticized for insufficient coverage, lack of connections to other transport modes, and safety issues.

Although private transport dominates internal commuting, the bus remains the primary mode of transportation for external travel—particularly for work. This dynamic forces residents to cover long distances within Maré—often on foot or using private transport—before even reaching formal public transit, increasing both travel time and cost (Redes da Maré, 2015).

- Social Housing

One of the city’s major issues is the housing deficit. The Metropolitan Region of Rio de Janeiro has one of the highest absolute housing deficits in the country—more than 400,000 housing units (FJP, 2024). In the Maré Complex, approximately 60% of households show some form of inadequacy, such as shared family occupancy or precarious construction (Redes da Maré, 2019).

The territorial configuration of Maré reveals a chronic absence of integrated urban planning, evidenced by the lack of zoning regulations to guide its sustainable development. The interventions that do take place in the neighborhood—when they occur—are marked by fragmented public actions, a mismatch with housing demands, and inappropriate models for local dynamics.

Table 2: Territorial configuration of Maré: Forms of occupation

Territorial Unit | Year of Foundation | Origem da construção | Programas |

Morro Do Timbau | 1940 | Spontaneous settlement |

|

Baixa do Sapateiro | 1947 | Spontaneous settlement |

|

Marcílio Dias | 1948 | Spontaneous settlement |

|

Parque Maré | 1953 | Spontaneous settlement |

|

Parque Rubens Vaz | 1954 | Spontaneous settlement |

|

Parque Roquete Pinto | 1955 | Spontaneous settlement |

|

Parque União | 1961 | Spontaneous settlement |

|

Nova Holanda | 1962 | Pub. Interv. State Gov. | COHAB |

Praia de Ramos | 1962 | Pub. Interv. State Gov. | COHAB |

Conjunto Esperança | 1982 | Pub. Interv. Federal Gov. | Projeto Rio |

Vila do João | 1982 | Pub. Interv. Federal Gov. | Projeto Rio |

Vila dos Pinheiros | 1983 | Pub. Interv. Federal Gov. | Projeto Rio |

Conj. Habitacional do Pinheiros | 1989 | Pub. Interv. Federal Gov. | Projeto Rio |

Conj. Bento Ribeiro Dantas | 1992 | Pub. Interv. Municipal Gov. | Morar Sem Risco Project |

Nova Maré | 1996 | Pub. Interv. Municipal Gov. | Morar Sem Risco Project |

Novo Pinheiros (Salsa e Merengue) | 2000 | Pub. Interv. Municipal Gov. | Morar Sem Risco Project |

Source: Redes da Maré, 2019.

Table 2 presents a detailed overview of the occupation process in each of the 16 favelas that make up the Maré Complex, including the origin of their formation. The analysis reveals a significant historical pattern: all occupations up to the mid-20th century were characterized by spontaneous settlement processes, as previously discussed in section 5.1.

Figure 3: Low-Income Settlement System / SABREN – Not to scale.

Source: IPP, 2021.

The map in Figure 3, extracted from the Low-Income Settlement System (Sabren), highlights a significant discrepancy between the official boundaries of the favelas and the actual extent of Maré’s territory. This cartographic inconsistency stems from institutional factors such as partial land regularization, outdated land-use classifications (zoning that fails to acknowledge consolidated settlements), and unrecorded expansion or reduction dynamics.

When compared with the information in Table 2, the housing complexes appear as islands in the southern part of the complex. This southern area (Vila do João, Vila dos Pinheiros, Conjunto Habitacional dos Pinheiros, Conjunto Bento Ribeiro Dantas, Salsa e Merengue) was the most affected by housing policies, being almost entirely composed of public housing developments.

In contrast, the Areas of Special Social Interest (AEIS) are limited to strategic axes (along the Linha Vermelha), where public facilities were built during major events. In other words, they only appear where urban planning interests justify interventions.

This spatial dynamic supports Rolnik’s (2015) thesis on selective urbanism, in which public policies and investments prioritize certain areas while marginalizing others, thereby perpetuating inequality. The AEIS and housing complexes operate as islands of governability within a sea of deliberately ignored informality.

- Facilities

In the Maré Complex, there is a significant concentration of cultural initiatives and educational institutions, predominantly municipal schools. In contrast, the availability of public sports and leisure facilities is limited, with the exception of the Maré Olympic Village. While there are some public spaces with multisport courts, many of these were built through community-led initiatives, highlighting the local mobilization to address structural deficiencies.

Self-management is a defining characteristic of the territory’s occupation, as exemplified by the Maré Museum, located in Nova Holanda and maintained by the community for the past 19 years. In the health sector, basic care units are predominant, while more complex healthcare services rely on the General Hospital of Bonsucesso — located near Morro do Timbau—and a nearby Emergency Care Unit (UPA).

In terms of public security, the 22nd Military Police Battalion is located at the edge of Maré, near the Linha Vermelha expressway, while the 21st Civil Police Precinct, which serves the area, is located in Higienópolis. There is also a fire station detachment at the Piscinão de Ramos, completing the network of emergency services available in the surrounding area.

- Social Vulnerability

Social vulnerability is a political concept that introduces new interpretive tools for understanding social development processes (Costa; Marguti, 2015), highlighting access to, absence of, or insufficiency in key aspects of social well-being. In this context, it refers to urban infrastructure, human capital, income, and employment. According to the Social Vulnerability Index (Costa; Marguti, 2015), the municipality of Rio de Janeiro is classified as having low vulnerability, with an average score of 0.290.

According to the Instituto Trata Brasil (2024), the city of Rio de Janeiro reports 93.82% coverage in water supply and 85.11% in sewage treatment. Specific indicators for the Maré neighborhood include:

- The Social Development Index is 0.547 (IBGE, 2010);

- According to the IBGE (2022), 97.13% of households located in favelas are connected to the public water supply, and 98.30% of residents have piped water within their homes (Redes da Maré, 2019, p. 63);

- 0.9% of households have water access only from external sources (Redes da Maré, 2019, p. 63);

- 71.50% of households have their garbage collected at the door (Redes da Maré, 2019, p. 64);

- 9.40% of adolescents aged 10 to 19 in Maré have had a child, the majority of whom are girls (14.40%) (Redes da Maré, 2019, p. 48);

- Although 94.97% of the favela population in the city is literate (IBGE, 2022), in Maré, 6% of individuals aged 15 or older are illiterate (Redes da Maré, 2019, p. 68).

These figures reveal that urban vulnerability affects Rio’s population unequally, with particularly severe structural deficits in favelas. While the city shows satisfactory aggregate indicators for basic sanitation, these services are precarious or absent in many informal settlements. The impact is especially harsh on specific groups, such as women, who make up the majority of the favela population and bear a double burden in managing households under deficient infrastructure conditions.

- Drugs, Violence, and Housing (or the Lack Thereof)

In 2020, more than 700 people were forced into homelessness as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (City of Rio de Janeiro, 2020). This situation was reflected across several neighborhoods in the city and was especially intensified in the Maré area, due to its location near major expressways. Numerous factors contribute to the presence of unhoused individuals in the region, primarily the existence of many vacant urban lots, favelas, and drug dealing points.

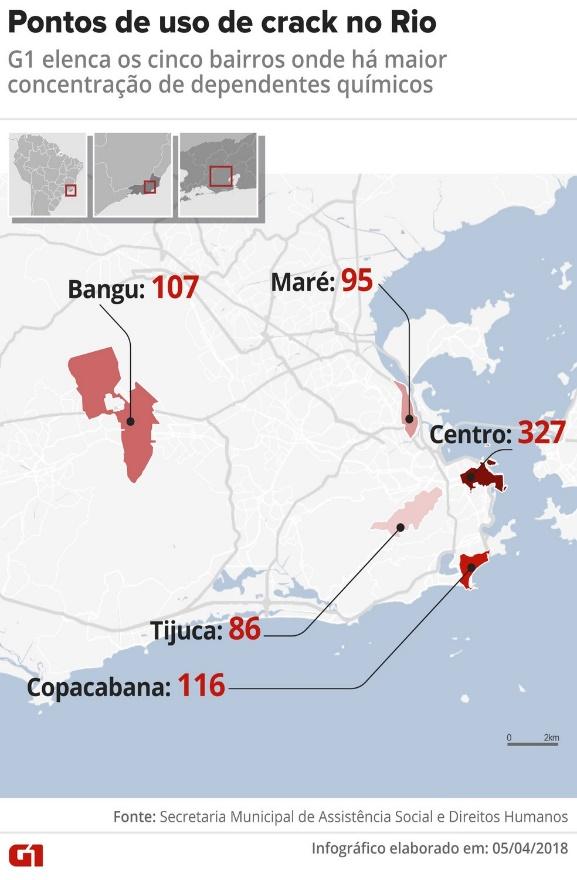

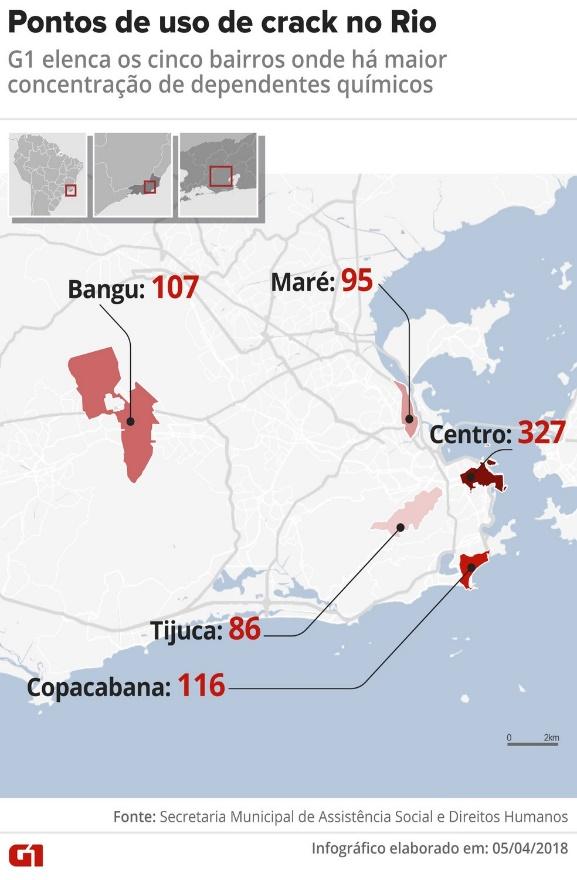

Figure 4 presents a map produced by G1 showing crack use hotspots across the city. This is one of the main drivers of increasing street homelessness, as crack users tend to concentrate in these areas, commonly referred to as cracolândias. In 2018, there were 95 crack consumption points identified within the Maré area. Above all, this is a public health issue, but one that also impacts regional safety.

Figure 5: Crack Use Hotspots in Rio

Source: G1, 2018

Another important point is that the favela complex is controlled by three different armed groups operating in close proximity. As a result, violent clashes are frequent, as are police incursions justified under the public security agenda. The 5th edition of the Right to Public Security in Maré Bulletin (Redes da Maré, 2020) presented 2020 data on armed violence in the area, aiming to “highlight the various dimensions of urban violence.” At the time of publication, a Supreme Federal Court (STF) injunction was in effect, prohibiting police operations in favelas due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This legal measure — Arguição de Descumprimento de Preceito Fundamental 635 (Claim of Noncompliance with a Fundamental Precept), or ADPF 635 — is widely known as the “Favelas ADPF.” It is a grassroots legal initiative that seeks to address the violence resulting from Rio de Janeiro's public security policies. Since its implementation, it has led to a 59% reduction in police operations, a 61% drop in overall deaths, and an 85% decrease in deaths caused by police action (from 34 in 2019 to 5 in 2020).

In 2024, the STF resumed hearings on ADPF 635, reigniting significant public debate. The measure has been the target of misinformation, with false claims misrepresenting it as a supposed “protection for armed groups and drug trafficking.” In reality, its intent is quite the opposite: to uphold fundamental rights in favelas by ensuring that police operations adhere to constitutional principles such as the right to life and due legal process.

Final Considerations

This study analyzed the neighborhood of Maré through the lens of the right to the city in vulnerable territories, linking this discussion to the concepts of non-place and urban voids. This approach enabled the identification of urban voids during the spatial diagnosis of the area, revealing patterns of space underutilization that reflect processes of socio-spatial exclusion.

To contextualize the analysis, the urbanization process of the municipality of Rio de Janeiro was examined through the perspective of territorial organization dynamics, showing its correlation with patterns of socio-spatial segregation in the city. This theoretical framework required a historical reconstruction of the urbanization of favelas since the 20th century. The connection between urban history and territorial analysis allowed for a deeper investigation of the formation of the Maré Complex and the identification of structural factors underlying its condition of social vulnerability.

Subsequently, through bibliographic research and territorial mapping, local problems and specificities were identified. In parallel, the use of different secondary data sources, including census data and research from various institutions, enabled a multidimensional approach to the area’s socio-spatial configuration.

This discussion is adapted from a broader academic project that includes an urban design proposal developed for the Maré Complex and its surroundings during the COVID-19 pandemic. This context directly impacted certain aspects of the analysis, such as the territorial diagnostic. For that reason, the non-governmental organization Redes de Desenvolvimento da Maré was essential to the study. Its publications provided more detailed data on the neighborhood’s favelas, especially the Maré Population Census, as well as informational bulletins, residents’ testimonials, and oral histories regarding the neighborhood’s formation.

Understanding local dynamics is essential when proposing any form of intervention or project aimed at improving the quality of life for residents and promoting sustainable development in the region. Therefore, this study was fundamental to understanding a territory that hosts a diverse population and faces socioeconomic, urban, and infrastructure challenges.

The Maré Complex stands as a powerful symbol of autonomy and resistance, demonstrating how grassroots initiatives can transform and strengthen the territory. The contextual analysis of a place that is both potent and marginalized brings to the forefront the importance of engaging with this population through strategies that are coherent with the relationships already established in the area. It highlights the need to engage in urban planning for favelas, to think of the right to the city beyond academic settings and government halls. This conversation must reach the people, especially those who have been historically silenced.

References

ABREU, Maurício de Almeida. Evolução urbana do Rio de Janeiro. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 2006.

AUGÉ, Marc. Não lugares: Introdução a uma antropologia da supermodernidade. Campinas: Papirus Editora, 2017.

BARROS, Alerrandre. Quase dois terços das favelas estão a menos de dois quilômetros de hospitais. Agência IBGE Notícias, 25 jun. 2019. Available at: https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-noticias/2012-agencia-de-noticias/noticias/27728-quase-dois-tercos-das-favelas-estao-a-menos-de-dois-quilometros-de-hospitais. Access in 27 nov. 2021.

BRASIL. Constituição (1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília, DF: Senado Federal: Centro Gráfico, 1988. Available at: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm.

COSTA, Marco Aurélio; MARGUTI, Bárbara Oliveira. Atlas da vulnerabilidade social nos municípios brasileiros. Brasília: IPEA, 2015. Available at: https://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/handle/11058/4381.

DE DUREN, Nora Libertun; OSORIO, Rene. Bairro: Dez Anos Depois. Washington, DC: BID, 2020. Available at: https://publications.iadb.org/pt/bairro-dez-anos-depois.

FERREIRA, Lara; OLIVEIRA, Paula; IACOVINI, Victor. Dimensões do Intervir em Favelas: desafios e perspectivas. 1. ed. São Paulo: Peabiru TCA, 2019.

FJP (FUNDAÇÃO JOÃO PINHEIRO). Déficit Habitacional no Brasil 2022. Belo Horizonte: FJP, 2024. Available at: https://fjp.mg.gov.br/. Access in 03 mar. 2025.

G1. Rio tem 150 pontos de uso de crack que reúnem 2 mil dependentes da droga; veja mapa. G1. 10 abr. 2018. Available at: https://g1.globo.com/rj/rio-de-janeiro/noticia/rio-tem-150-pontos-de-uso-de-crack-que-reunem-2-mil-dependentes-da-droga-veja-mapa.ghtml. Access in 27 nov. 2021.

HARVEY, David. The Right to the City. New Left Review, 2008. Available at: https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii53/articles/david-harvey-the-right-to-the-city.

HERTZBERGER, Herman. Lições de arquitetura. 3. ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2015.

IBGE - INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA. Panorama do Censo Demográfico 2022. Indicadores. Brasil. Available at: https://censo2022.ibge.gov.br/panorama/indicadores.html?localidade=BR. Access in 03 mar. 2025.

IPP – INSTITUTO MUNICIPAL DE URBANISMO PEREIRA PASSOS. Datario. Sistema de Assentamentos Baixa Renda (Sabren). 2021. Rio de Janeiro: IPP, 2021. Available at: https://www.data.rio/apps/PCRJ::sabren/explore. Access em 27 nov. 2021.

ITB – INSTITUTO TRATA BRASIL. Tabela Resumo – Ranking do Saneamento 2024. Trata Brasil. Available at: https://tratabrasil.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Tabela-Resumo-Ranking-do-Saneamento-de-2024-TRATA-BRASIL-GO-ASSOCIADOS.pdf. Access in 03 mar. 2025.

LEFEBVRE, Henri. O direito à cidade. 5. ed. São Paulo: Centauro Editora, 2008.

MAGALHÃES, Luiz Ernesto. TCM lista 133 metas que a Prefeitura do Rio traçou e não conseguiu alcançar em 2018. O Globo, 2019. Available at: https://oglobo.globo.com/rio/tcm-lista-133-metas-que-prefeitura-do-rio-tracou-nao-conseguiu-alcancar-em-2018-23795890. Access in 27 nov. 2021.

MENDES, Izabel Cristina Reis. Programa favela-bairro: uma inovação estratégica? Estudo do programa favela-bairro no contexto do plano estratégico da cidade do Rio de Janeiro. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, 2006.Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/d.16.2006.tde-03052007-144846.

PREFEITURA DA CIDADE DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Censo da População em Situação de Rua 2020. Rio de Janeiro: Prefeitura da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, 2020. Available at: https://psr2020-pcrj.hub.arcgis.com/. Access in 27 nov. 2021.

REDES DA MARÉ (REDES DE DESENVOLVIMENTO DA MARÉ). et al. Memória e Identidade dos Moradores de Nova Holanda. 1. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Redes de Desenvolvimento da Maré, 2012. Available at: https://www.redesdamare.org.br/media/livros/memoria-identidade-moradores-nova-holanda.pdf.

REDES DA MARÉ (REDES DE DESENVOLVIMENTO DA MARÉ). et al. Memória e identidade dos moradores do Morro do Timbau e Parque Proletário da Maré. 1. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Redes de Desenvolvimento da Maré, 2013. Available at: https://www.redesdamare.org.br/media/livros/Memoria-identidade-moradores-morro-timbau.pdf.

REDES DA MARÉ (REDES DE DESENVOLVIMENTO DA MARÉ). 1a Amostra sobre Mobilidade na Maré. 1. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Redes de Desenvolvimento da Maré, 2015. Available at: https://www.redesdamare.org.br/media/livros/MobilidadeMare_WEB.pdf.

REDES DA MARÉ (REDES DE DESENVOLVIMENTO DA MARÉ). Censo Populacional da Maré. Rio de Janeiro: Redes de Desenvolvimento da Maré, 2019. Available at: https://www.redesdamare.org.br/media/downloads/arquivos/CensoMare_WEB_04MAI.pdf.

REDES DA MARÉ (REDES DE DESENVOLVIMENTO DA MARÉ). Boletim Direito à Segurança Pública na Maré. Rio de Janeiro: Redes de Desenvolvimento da Maré, 2020. Available at: https://www.redesdamare.org.br/media/downloads/arquivos/Boletim-Direito-Seguranca-Publ.pdf.

RIBEIRO, Luis Cesar de Queiroz. Rio de Janeiro: metamorfoses da ordem urbana da metrópole brasileira: o caso do Rio de Janeiro. In: RIBEIRO, Luis Cesar de Queiroz; RIBEIRO, Marcelo Gomes (org.) METRÓPOLES BRASILEIRAS: Síntese da transformação na ordem urbana 1980 a 2010. Rio de Janeiro: Letra Capital Editora, 2018. Cap. 9, p. 252-281. Available at: https://biblioteca-repositorio.clacso.edu.ar/libreria_cm_archivos/pdf_2115.pdf.

RODRIGUES, Rute Imanishi. Decifrando as origens dos complexos de favelas: algumas evidências sobre o Rio de Janeiro. Revista de Pesquisa em Arquitetura e Urbanismo, v. 18, 2020.

ROLNIK, Raquel. Guerra dos Lugares: A colonização da terra e da moradia na era das finanças. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2015.

SILVA, Claudia Rose Ribeiro da. Maré: A Invenção de um Bairro. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 2006.

TORRES, Pedro Henrique Campello. “Avenida Brasil – Tudo Passa Quem Não Viu?”: formação e ocupação do subúrbio rodoviário no Rio de Janeiro (1930-1960). Revista Brasileira de Estudos Urbanos e Regionais, v. 20, n. 2, p. 287, 2018.

VILLAÇA, Flávio. Reflexões sobre as cidades brasileiras. 1. ed. São Paulo: Studio Nobel, 2012.

XIMENES, Luciana Alencar; JAENISCH, Samuel Thomas. As favelas do Rio de Janeiro e suas camadas de urbanização. Vinte anos de políticas de intervenção sobre espaços populares da cidade. In: Anais XVIII ENANPUR. [s.l.: s.n.], 2019. Available at: https://habitacao.observatoriodasmetropoles.net.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/ENANPUR-2019.pdf.

About the Author

Sarah Ferreira is a master's student in the Graduate Program in Population, Territory, and Public Statistics at the National School of Statistical Sciences (ENCE/IBGE), where she researches the socio-territorial dynamics of favelas, focusing on the right to the city and racial and gender relations. Simultaneously, she is pursuing a postgraduate specialization in Environmental Analysis and Territorial Management. She earned her degree in Architecture and Urbanism from Universidade Veiga de Almeida (UVA) in 2021, at the age of 24, shaping her academic background with a critical perspective on urban planning and socio-spatial inequalities. Born and raised in Ilha do Governador, in the northern zone of Rio de Janeiro, Sarah lives in the Bairro Nossa Senhora das Graças favela—an experience that deeply informs her academic path and activism. Her research is driven by the desire to give visibility to peripheral narratives, challenge stereotypes, and contribute to more inclusive urban policies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.B.F.; methodology, S.S.B.F.; software, S.S.B.F.; validation, S.S.B.F.; formal analysis, S.S.B.F.; investigation, S.S.B.F.; resources, data curation, S.S.B.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.B.F.; writing—review and editing, visualization, S.S.B.F.

Funding

This work was supported by the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES) – Funding Code 001.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the contributions of the City of Rio de Janeiro and its agencies: the Pereira Passos Municipal Institute for Urban Planning (IPP) and the Municipal Department of Urban Planning (SMU); the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE); the Trata Brasil Institute; the João Pinheiro Foundation (FJP); the organization Redes de Desenvolvimento da Maré; and the Center for Studies and Solidarity Actions of Maré (CEASM).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

About Coleção Estudos Cariocas

Coleção Estudos Cariocas (ISSN 1984-7203) is a publication dedicated to studies and research on the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, affiliated with the Pereira Passos Institute (IPP) of the Rio de Janeiro City Hall.

Its objective is to disseminate technical and scientific production on topics related to the city of Rio de Janeiro, as well as its metropolitan connections and its role in regional, national, and international contexts. The collection is open to all researchers (whether municipal employees or not) and covers a wide range of fields — provided they partially or fully address the spatial scope of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Articles must also align with the Institute’s objectives, which are:

- to promote and coordinate public intervention in the city’s urban space;

- to provide and integrate the activities of the city’s geographic, cartographic, monographic, and statistical information systems;

- to support the establishment of basic guidelines for the city’s socioeconomic development.

Special emphasis will be given to the articulation of the articles with the city's economic development proposal. Thus, it is expected that the multidisciplinary articles submitted to the journal will address the urban development needs of Rio de Janeiro.

[1] Cracolândia" (derived from crack + lândia, meaning “territory”) is a place where drug-dependent individuals live, generally users of crack cocaine.

[2] The term emerged after the publication of "Anti-homeless spikes are part of a wider phenomenon of ‘hostile architecture’" by British newspaper The Guardian, written by journalist Ben Quinn in 2014.

[3] A set of laws and guidelines designed to regulate land use and territorial development in a city. Every municipality with more than 20,000 inhabitants is required to develop its own master plan; therefore, most Brazilian cities have a Master Plan (Plano Diretor).

[4] In the case of urban property that is unbuilt, underutilized, or unused, Article 182 establishes the instrument through compensation paid in “public debt bonds issued with prior approval from the Federal Senate.”

[5] The study initially states that 88 favelas were addressed by the intervention; however, it specifies that the actual number is higher, as some are part of clusters or complexes. Therefore, when counted individually, the total amounts to 143.

[6] Some of these favelas are considered clusters or complexes, while others are nearby favelas, but not necessarily contiguous, as is the case with the PAC of the Complexo da Tijuca.

[7] Between 1949 and 1952, the Fundão Archipelago was drained, and the islands were annexed, forming Fundão Island.

[8] By this time, the area had already formed a large set of slums built on stilts. In 1961, for example, the last slum created by spontaneous occupation, Parque União, was established.

[9] The 2022 Census has some methodological limitations that prevent its comparison with the Maré Census, such as: it does not consider housing complexes as slums; there was a change in the census sectors; there was a change in the methodology and the description of the concept of slums and urban communities; among others.