Volume 13 Issue 2 *Corresponding author souzayt3@gmail.com Submitted 19 mar 2025 Accepted 19 may 2025 Published 01 jun 2025 Citation SOUZA, Y. E. T.; COSTA, H. S. M. Urban Agriculture and Nature in/of Urban Planning: a review at the Federal and Carioca levels. Coleção Estudos Cariocas, v. 13, n. 2, 2025.

DOI: 10.71256/19847203.13.2.137.2025 The article was originally submitted in PORTUGUESE. Translations into other languages were reviewed and validated by the authors and the editorial team. Nevertheless, for the most accurate representation of the subject matter, readers are encouraged to consult the article in its original language.

| Urban Agriculture and Nature in/of Urban Planning: a review at the Federal and Carioca levels A agricultura urbana e a natureza no/do planejamento urbano: uma revisão a nível federal e carioca La agricultura urbana y la naturaleza en/del planeamiento urbano: una revisión a nivel federal y carioca Yago Evangelista Tavares de Souza1* and Heloisa Soares de Moura Costa² 1Universidade Federal Fluminense - Av. Gal. Milton Tavares de Souza, s/nº, Campus da Praia Vermelha, Niterói/RJ, CEP 24210 346, ORCID 0000-0001-6486-552X, souzayt3@gmail.com 2Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais - Av. Pres. Antônio Carlos, 6627 - Pampulha, Belo Horizonte, MG, 31270-901, ORCID: 0000-0003-0132-5918,hsmcosta@geo.igc.ufmg.br

AbstractThis article analyzes the evolution of urban planning policies related to nature and urban agriculture, based on federal and Rio de Janeiro legislation. The research covers documents such as the 1976 Draft Urban Development Bill and Law No. 6766/1979, discussing the impact of public policies on urban configuration and the challenges faced by small farmers. The research draws on documents retrieved from the Municipal Council website and the Official Gazette of the Municipality. This text aims to contribute to the debate on urban planning, particularly regarding issues related to nature. Keywords: Urban Planning, Urban Nature, Urban Agriculture, Public Policies, Rio De Janeiro.

ResumoEste artigo analisa a evolução das políticas de planejamento urbano ligadas à natureza e à agricultura urbana, com base em legislações federais e do Rio de Janeiro. A pesquisa abrange documentos como o Anteprojeto de Lei de Desenvolvimento Urbano de 1976 e a Lei nº 6766/1979, discutindo o impacto das políticas públicas na configuração urbana e nos desafios enfrentados por pequenos agricultores. Os dados foram coletados no site da Câmara Municipal e no Diário Oficial do Município. Este texto tem como objetivo contribuir para o debate sobre o planejamento urbano, particularmente no que se refere às questões relacionadas à natureza. Palavras-chave: Planejamento Urbano, Natureza Urbana, Agricultura Urbana, Políticas Públicas, Rio de Janeiro.

ResumenEste artículo analiza la evolución de las políticas de planificación urbana relacionadas con la naturaleza y la agricultura urbana, basándose en legislaciones federales y del municipio de Río de Janeiro. La investigación abarca documentos como el Anteproyecto de Ley de Desarrollo Urbano de 1976 y la Ley nº 6766/1979, discutiendo el impacto de las políticas públicas en la configuración urbana y los desafíos que enfrentan los pequeños agricultores. Los datos fueron recolectados en el sitio web de la Cámara Municipal y en el Diario Oficial del Municipio. Este texto tiene como objetivo contribuir al debate sobre la planificación urbana, particularmente en lo que respecta a las cuestiones relacionadas con la naturaleza. Palabras clave: Planificación Urbana, Naturaleza Urbana, Agricultura Urbana, Políticas Públicas, Río De Janeiro.

|

Introduction

This article addresses how issues of nature and urban agriculture have evolved over the years within urban planning policies. Initially, it works with a series of six federal urban policy texts: 1) the Urban Development Bill Draft of 1976; 2) Federal Law on Land Subdivision No. 6766, of December 19, 1979; 3) the Urban Development Bill Draft of 1982; 4) Chapter II - On Urban Policy, more specifically Articles 182 and 183, of the Federal Constitution of 1988; 5) the Popular Amendment for Urban Reform of 1988; and 6) Law No. 10.257, of July 10, 2001, which regulates articles 182 and 183 of the Federal Constitution, establishes general guidelines for urban policy and provides other measures.

After addressing nature and urban agriculture in these texts, the article conducts a general review of the master plans of the city of Rio de Janeiro, using four texts from 1976 to 2021: 1) Municipal Decree No. 322, of March 3, 1976, and its subsequent amendments; 2) the Ten-Year Master Plan of the City of Rio de Janeiro, implemented by Complementary Law No. 16, of June 4, 1992; 3) the Master Plan for Urban and Sustainable Development of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, approved by Complementary Law No. 111, of February 1, 2011; and 4) the text of Complementary Bill No. 44/2021, which establishes the revision of the Sustainable Urban Development Master Plan, sent to the Municipal Chamber of Rio de Janeiro on September 21, 2021.

It is thus possible to follow how the federal guidelines provided in these texts and the master plans of the city of Rio de Janeiro addressed the subject over these years. Historically, the first Master Plans focused almost exclusively on consolidated urban areas, disregarding rural and peri-urban zones as an essential part of the city. Only in recent decades, driven by new paradigms of planning and sustainable development, have these areas come to be recognized as fundamental to urban dynamics, which required their integration into municipal planning instruments.

First, it is important to define how the issue of nature will be addressed in this text. Four points were observed in the analyzed texts: 1) forests, woodlands and similar; 2) watercourses, water bodies and other hydrographic forms; 3) forms of land use permitted in these environments; and, finally, 4) the use of nature, which relates to work and subsistence, especially with farmers and animal husbandry and care.

In addition to conducting this search in Rio de Janeiro's urban legislation in recent decades on the municipal chamber website, particularly the city's master plans, terms such as "urban agriculture," "urban gardens," and "family farming" were also researched in the municipality's official gazette. The intent behind this was to find public policies related to the topic, but it was also interesting to find reports from popular participation forums on the theme, which enriched the research, as it was possible to know the opinion of popular movements about what was happening at the time.

Additionally to these bibliographic analysis procedures, an email interview was conducted with one of the members of the Municipal Secretariat of Urbanism (SMU) in which the questions were related to the most recent changes in master plans, from the early 2000s until now. No questions were asked regarding earlier periods because it was believed that the technicians at city hall were not there before the 1990s.

A point to be clarified is that while this text was being written, there were several changes in the Master Plan text, more changes than it was possible to follow. The version analyzed here is the one delivered to the Municipal Chamber on September 21, 2021. Since then, the text has undergone revisions in the Chamber, and some points of Urban Agriculture (UA) were improved, others maintained, and some ended up being removed.

This work is not the first to conduct a review of master plans; one of the works oriented in this direction was the elaboration of the Integrated Development Master Plan (PDDI-RMBH), which sought to articulate various master plans of the municipalities in the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte (RMBH). One of the aspects addressed in this process was how these legislations treat the rural zones of these municipalities. In this context, Bianca Mariquito Naime Silva (2012), in her undergraduate thesis, conducted a survey of how the master plans of these municipalities approach this:

It was verified, through a previous reading of the Master Plans, that their rural areas are little mentioned in the plan, do not have macro-zoning and there is no precise survey of information regarding their population, the activities they perform, types of soils and the various uses of rural space. (Silva, 2012, p. 35)

As will be seen later, this pattern noted in the RMBH plans is also repeated in the master plans of the municipality of Rio de Janeiro, at least until the 2021-22 Plan is approved. This indicates that, in general, master plans do not demonstrate significant concern with the approach to rural zones.

Costa et al (2010) speak of "generalized reduction, or even extinction, in some cases, of the rural areas of municipalities" (Costa et al, 2010, p. 21) and how, even if there is insertion of areas destined for urban agriculture within the urban area of the municipality,

such activities will occur in the form of family farming or small property, since the general tendency is for elevation of land price levels and, consequently, also inhibiting social housing projects. (Costa et al, 2010, p. 22).

What is observed in the last Master Plan of Rio de Janeiro, under discussion in the City Council until January 16, 2024, is the extinction of the urban perimeter and the liberation of urban agriculture practice throughout the city's territory, accompanied by the designation of a specific agricultural zone. This change, on one hand, is positive, as it allows agricultural practice throughout the municipality and, at the same time, directs specific zones to deal with localized conflicts. On the other hand, recognizing this advance also implies considering the challenges faced by small farmers, collective practices, and family farming in urban expansion areas and areas of high real estate interest. The pressure of urbanization may compromise the permanence and viability of these initiatives.

Costa et al (2011) analyze the environmental approach contained in master plans based on state reports produced by the Network for Evaluation and Capacity Building for the Implementation of Participatory Master Plans in five different regions of the country. The research identified recurring environmental issues, possibly associated with biomes or landscape units. Although it was not possible to draw a homogeneous profile of how environmental themes are treated in municipalities, the predominance of incorporating discourses linked to sustainability and environmental quality was observed. However, mechanisms capable of giving concreteness to environmental policy were not foreseen. In some cases, the environmental issue appears peripherally, limited to isolated provisions in the documents.

Furthermore, Costa et al (2011) show that Environmental Zoning is what comes closest to the reality of territories and what tries to be more propositional in terms of society-nature reconciliation – but, if differentiated use and occupation criteria are not established, the policy's effectiveness is lost – and that there is a tradition of master plans limiting themselves to establishing guidelines for urban and urban expansion areas, neglecting conflicts of land use and occupation and the socio-environmental relations of rural areas.

The relevance of this study lies in evidencing how urban agriculture, previously marginalized in urban planning, came to be incorporated as a strategic instrument for combating food insecurity and promoting urban sustainability. Understanding this evolution is fundamental for improving public policies and more inclusive urban practices.

Federal urban legislation

Monte-Mór (2007) addresses the urban policy of the military regime, showing it to be very much based, mainly, on the National Housing Bank (BNH), established by Law No. 4.380, of August 21, 1964, as a result of the National Housing Plan, and on the Federal Housing and Urbanism Service (SERFHAU), established by the same law. SERFHAU was responsible for elaborating and coordinating national policy in the field of integrated local planning, established within the guidelines of regional development policy. There were very strong sectoral policies, especially in the 1970s, and, in the second half of that same decade, a National Urban Policy was created.

In this context, initiatives within the government itself attempted to articulate Law projects related to the then-called urban development: the 1976 Bill Draft elaborated by the National Commission for Metropolitan Regions and Urban Policy (CNPU), and the 1982 Bill Draft coordinated by the National Council for Urban Development (CNDU). It is relevant to highlight the approval of Law 6.766 of 1979. On the other hand, the idea of urban reform, initiated in 1963, remained alive, although dormant, during the military period.

In the 1980s, movements for redemocratization began, such as Diretas Já, popular and civil society initiatives gained strength and culminated in the constituent process initiated in 1986. The new Constitution provided for the opening for the presentation of the so-called popular amendments to the draft, Urban Reform was among the proposals submitted.

The Urban Development Bill Draft of 1976, sometimes called the "Grandfather of the City Statute," was an attempt to structure a proposal for national urban legislation. Despite having been poorly received by various sectors of society at the time, the document, published in the Estadão newspaper for public debate, contained proposals that persist to this day, for example, encouraging popular participation in urban debates and the creation of special zones of social interest, among others.

The text proposal presented broad guidelines for municipalities to legislate about their own spaces and lay foundations for discussions such as land ownership and specific "zoning" (e.g. Areas for Industrial Use, Environmental Protection Areas, etc.). One of these guidelines was the division of the municipality into three zones: urban, urban expansion and rural. The urban is defined by what is within an urban perimeter established by management – and part of what is understood as urbanization are the subdivision, resubdivision and remembrance of rural properties –, but the text does not define, at any moment, what would be the rural zone of the municipality. This suggests an eliminative process, any area outside the urban perimeter being rural, a practice that still persists today.

Regarding green areas, the draft adopts a conservationist perspective, which is not open to uses, at least not explicitly, even if sustainable[1]. Urbanization is presented as a way to minimize environmental impact; often, the text touches on the idea of basic sanitation and how this would be intrinsically linked to urbanization.

The Federal Land Subdivision Law No. 6.766 of 1979, in turn, is focused mainly on urban land subdivision rather than on the rural issue itself, which is not mentioned in the text. The environmental agenda was only explicitly incorporated into the text after amendments already in the early 2000s. Even so, the law already provided for important environmental criteria linked to land subdivision parameters, such as slope control, topography, reservation of green areas, among others.

In the changes of the 2000s, the main point addressed is the water issue, both guaranteeing a marginal strip and conserving river courses and water management[2]. Apart from this, there are not many mentions of environmental and rural issues, which is expected, but it is interesting to see that the environmental issue is still treated here with a conservationist vision, which is not open to other uses of the environment, it is once again a bet that nature should remain untouched.

The Urban Development Bill Draft of 1982 is a law proposal much more similar to that of the 1977 Draft than to the others, because the idea is also to give general guidelines on urban planning and guiding principles. Once again, as in 1977, the 1982 Draft sees urban planning as a possibility for reducing environmental impact[3][4] or environmental recovery.

The first definition of urbanization that appears in the text is precisely the transformation of rural areas into urban ones, as in the 1977 text, the territory is divided into three parts of possible "zoning," urban area, urban expansion and rural, but what is most interesting here for the text are the restricted urbanization areas:

§ 2: Restricted urbanization areas are those in which urbanization should be discouraged or contained as a result of:

a) their natural elements and characteristics of physiographic order (Urban Development Bill Draft of 1982, p. 166)

This definition reinforces the preservationist character that marks the urban legislation of the 1970s and 1980s. In more recent years, significant progress is observed, as exemplified by the Strategic Master Plan of the Municipality of São Paulo of 2014, with the creation of the Special Zone of Social Interest (ZEIS) 4. This zone recognizes specific forms of housing within environmental protection areas, aiming at the conversion of these areas into a safe settlement or the relocation of people to a safer location.

ZEIS 4 are areas characterized by unbuilt lots or plots adequate for urbanization and construction situated in the Water Source Protection Area of the hydrographic basins of the Guarapiranga and Billings reservoirs, exclusively in the Macro-areas of Vulnerability Reduction and Environmental Recovery and Urban and Environmental Control and Recovery, destined for the promotion of Social Interest Housing to serve families residing in settlements located in the referred Water Source Protection Area, preferably as a result of resettlement resulting from an urbanization plan or from the evacuation of risk areas and permanent preservation, in compliance with state legislation. (São Paulo, 2014, p. 4).

In discussions of the current Master Plan of Rio de Janeiro, the possibility of creating a ZEIS with similar characteristics circulated, aimed at regularizing the Horto Favela, located in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro, in the Botanical Garden neighborhood. This favela is located, in part, in an environmental protection area, and there have been several attempts to remove the community, especially in recent years, none of them fully successful.

The Urban Policy Chapter of the Federal Constitution, specifically Articles 182 and 183, is relatively superficial regarding the themes discussed, focusing mainly on the issue of land ownership.

In the City Statute (Brazil, 2001) it is possible to identify a greater concern with sustainability and environmental issues. In the mentioned 1977 and 1982 drafts, concern with the environment is restricted to only one of the objectives of urbanization, while in the City Statute, the main concern seems to be sustainability[5]. Not only that, but the previous drafts demonstrate that environmental preservation would be achieved through the advancement of urbanization, as seen in the 1977 one, where the main environmental concern is the sewage issue. The rural issue does not appear centrally in the text, only defining the issue of adverse possession, which is extended to rural properties. What is also interesting in the text is the idea of complementarity between rural and urban[6].

Master plans and other urban policies of Rio de Janeiro municipality

Municipal Decree No. 322, of March 3, 1976, during the municipal administration of Marcos Tamoyo from the National Renewal Alliance party, delimits agricultural production to Residential Zone - 6 (ZR-6) and to Neighborhood Centers (CB) 1, 2, 3, that is, the CBs of ZR-6, and regulates it through Article 23, which states that

Activities of agriculture and livestock, horticulture, floriculture, arboriculture, aviculture, cuniculture, caniculture, small animal breeding, apiculture, sericulture, slaughterhouse and abattoir are tolerated in ZR-6 and in CB of ZR-6 (RIO DE JANEIRO, p. 10, emphasis mine)

This region today would be equivalent, approximately, to the neighborhoods of Campo Grande and Bangu. Unfortunately, it is difficult to find a map that shows the zoning of Rio de Janeiro municipality in 1976. However, a master's dissertation from PUC-Rio (Santos, 2012) makes reference to a map prepared by the former Legal Engineering Institute that shows the Zones at the time. Unfortunately, the map was altered to mark the study area, Planning Area - 3, and the map source is not cited, and, despite not affecting the identification of ZR-6 and agricultural zones, it is not an ideal map, but it helps in visualizing the region.

Figure 1 - Zoning Map of Decree 322/1976

Source: Legal Engineering Institute (IEL) apud Santos (2012).

Although the text presents a level of concern with environmental issues, it is not treated as a central theme or as part of an important debate. There is, however, a mention about pollution caused by industries, which should be limited to only certain parts of the city. It is not surprising that environmental issues are not treated in depth, since none of the texts discussed above, published until 1976, view this issue deeply, only Environmental Protection Zones with total use restriction are delimited.

The ten-year Master Plan of Rio de Janeiro municipality, implemented by Complementary Law No. 16, on June 4, 1992, during the municipal administration of Marcello Alencar from the Democratic Labor Party, brought interesting advances: an Agricultural Zone was implemented and along with it were also implemented Zones for residential, commercial and service, and industrial use. The Agricultural Zones were constituted within the macrozoning of restriction to urban occupation.

The macrozones of restriction to urban occupation are:

I - those with physical conditions adverse to occupation;

II - those destined for agricultural occupation;

III - those subject to environmental protection;

IV - those inappropriate for urbanization (Rio De Janeiro, 1992, n.p.).

This macrozone is doubly interesting for the purpose of this text, as it encompasses both environmental protection zones and zones destined for agricultural occupation, which, in fact, seems more like a grouping of everything that was understood as non-urban or that would not serve urbanization.

The agricultural zones are delimited as follows:

Art. 49 Agricultural areas shall be delimited with a view to maintaining agricultural and livestock activity and shall comprise areas with agricultural vocation and others inappropriate for urbanization, recoverable for agricultural use or necessary for maintaining environmental balance.

§ 1º Agricultural areas may accommodate residential uses with low density, commercial and service activities complementary to agricultural and residential use, agro-industries and tourist, recreational and cultural activities, in sites and farms.

§ 2º The use and occupation of agricultural areas shall observe the following guidelines:

I - prohibition of subdivision into small lots by establishing minimum agricultural lots, according to the characteristics of each area;

II - prohibition of occupation by housing complexes and high-density residential use;

III - establishment of occupation parameters for protection of agricultural use in transition strips between agricultural areas and urban or urban expansion macrozones. (Rio de Janeiro, 1992, n.p.).

This ten-year plan is very concerned with agricultural issues and with guaranteeing spaces that are dedicated to cultivation and animal breeding[7][8]. It is interesting to note that this plan manages to reconcile urban land use in areas of environmental fragility with urban agriculture.

§ 4º Fragile lowland areas[9] may accommodate agricultural, leisure and low-density residential uses, these being conditioned to the realization of macro-drainage works and to the redefinition of threshold levels of buildings. [...]

Art. 51 Areas subject to environmental protection are susceptible to restricted residential or agricultural occupation and uses such as leisure or ecological research, with the exception of areas classified as biological reserves. (Rio de Janeiro, 1992, n.p.).

This Master Plan managed to treat this very delicate theme in a way well ahead of its time, since in 1992 environmental discussions and about urban agriculture were just beginning to gain prominence. Laschefski (2019) highlights the importance of ECO-92, held in Rio de Janeiro, for establishing environmental policies at a global level. Many cities began to incorporate the environmental agenda in their plans and actions, but even so, the approval of this type of law can be considered a significant advance for urban agriculture movements even today.

The last topics of this Master Plan that deserve to be touched upon are support for agricultural production and commercialization and the stimulus to organic fertilization and the conciliation or consortium of plant species.

II - regarding the development of the primary sector:

a) stimulus to agricultural activities through support to the production and commercialization system;

[...]

c) support for initiatives to integrate agriculture with industry and services;

d) development of fishing activity, with support for commercialization and industrialization;

e) stimulus and diffusion of agricultural practices using organic soil fertilization, use of biological pesticides and adoption of crop rotation and plant species consortium (Rio de Janeiro, 1992, n.p.).

This is the first of the master plans that is already under the order of the 1988 Constitution and, although it does not touch much on urban planning issues, the Plan proved to be quite diverse in its application.

The macrozoning of restriction to urban occupation is defined by Annex III of the text and consists of various coastal regions, in the Tijuca Massif, in some hills of the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro, especially the mountain top areas, and in some regions of the West Zone of the city. Once again, here we can note some type of incentive to urban agriculture in the West Zone of the city.

The Master Plan for Urban and Sustainable Development of Rio de Janeiro Municipality, approved by Complementary Law No. 111, of February 1, 2011, during the municipal administration of mayor Eduardo Paes, at the time affiliated with the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, brings many points similar to the 1992 Law, such as, for example, the incentive to use agriculture in floodplain and water recharge areas, and also an extensive incentive to urban agriculture, which is even one of the Plan's guidelines.

Art. 3º The urban policy of the Municipality aims to promote the full development of the social functions of the City and urban property through the following guidelines:

[...] II - conditioning urban occupation to the protection of massifs and hills, forests, the maritime shore and water bodies of the city's reference landmarks, landscape, agricultural areas and the cultural identity of neighborhoods;

[...] XVII - revitalization and promotion of agricultural and fishing activities, with incentive to forms of associativism and the structuring of promotion policies and provision of technical assistance; (Rio de Janeiro, 2011a, n.p.).

One aspect that distinguishes Rio de Janeiro city planning is that there is no urban perimeter, and the entire municipal area is considered urban. This is a strategy that is repeated to this day in the Master Plan. Despite this, Article 13 of the 2011 Plan emphasizes that

The characterization of the municipal territory as entirely urban does not exclude the existence of areas destined for agricultural activities or the establishment of urban and environmental restrictions to the occupation of certain parts of the territory. (Rio de Janeiro, 2011a, n.p.).

In the interview with City Hall technicians, a question was asked about this change for the municipality to be entirely urban. The response from the technical staff was:

A hypothesis raised during the period I worked at the current Municipal Secretariat of Urban Development (SMPU), former Municipal Secretariat of Urbanism, for the categorization of the Rio territory as a city is the possibility of collecting the Urban Property Tax - IPTU, considering its municipal competence and its territorial scope, which depends on the delimitation given by the Master Plan (PD), instead of the Rural Property Tax - ITR, of federal competence. I consider it important to verify the hypothesis with the team responsible for the Master Plan revision that works at SMPU[10].

The mention of urban agriculture is the verification of this activity in the municipality, as well as other activities of the first sector of the economy. The restriction areas mentioned in the 2011 Master Plan are the verification in the legal text of the importance of portions of the territory that provide environmental services of a hydrological and climatological nature fundamental to the city, in addition to constituting important ecosystems and/or landscapes that compose Rio de Janeiro's identity.

I add that the 1992 PD does not mention the issue of urban perimeter, but says, in Art. 105 that "For control of land use and occupation, the Municipality shall be divided into Zones, which may contain, in whole or in part, Areas of Special Interest. § 1° - Zone is the space of the City perfectly delimited by its environmental characteristics, for which demographic density controls and construction limits and the intensity of various uses and economic, social and cultural activities will be provided. § 2° - The Zones will not be superimposed and will cover the totality of the municipal territory." Article 106 included an agricultural zone: "Art. 106 - The Zones will have the following denominations and concepts:.... VI - Agricultural Zone is that where agricultural and animal breeding activities prevail and that of support and complementation compatible with each other." (Interview conducted by email on July 18, 2023)

Despite the attempt to encompass urban agriculture as a whole and not create barriers for farmers, Elisa Zukeran (member of the National Supply Company, Conab), at the time counselor in one of the city hall's popular participation forums, cites the fact that Rio de Janeiro Municipality is considered urban and that for this reason farmers were unable to obtain credit for the National Program for Strengthening Family Agriculture (Pronaf) (Rio de Janeiro, 2011b, p. 82)[11].

The greatest advance of this Plan may be containing a section that deals specifically with urban agriculture and fishing:

Section IV - On Agriculture, Fishing and Supply Subsection I - On Objectives

Art. 253. The objectives of the municipal Agriculture, Fishing and Supply Policy are:

I - increase agricultural and fishing production, based on community relations and sustainability as a strategy for providing cheaper products for city supply;

II - rescue the agricultural vocation of urban areas, through the development of programs and actions to encourage production and improve the living conditions of farmers;

III - map and title areas with agricultural vocation and tradition;

IV - reinsert, in the medium term, agricultural and fishing production in the municipality's economy actively;

V - encourage organic agriculture and responsible artisanal fishing;

VI - create a municipal supply program.

Subsection II - On Guidelines

Art. 254. The guidelines of the Agriculture, Fishing and Supply Policy are:

I - implementation of institutional or subsidized agriculture projects in idle areas, urban voids or areas inappropriate for occupation;

II - promotion and incentive to cooperativism in agricultural, fishing and supply activities;

III - development of mechanisms that enable Rio farmers to access official agricultural credit lines;

IV - prioritization of adopting direct commercialization actions, in order to boost the flow of municipal production;

V - maintenance of areas with agricultural tradition, contributing to the dynamization of the economy;

VI - establishment of official agricultural credit lines destined to Rio rural producers.

Art. 255. The Fishing Promotion Program shall comprise permanent control of fish quality, in relation to water pollution, and the implementation of permanent water quality monitoring of fishing water resources.

Art. 256. The Sustainable Agriculture Promotion Program shall comprise the realization of programs for generating organic compost - fertilizer, from selective waste collection and recycling and the reuse of organic sewage. (Rio de Janeiro, 2011a, n.p., emphasis mine).

The text of the 2011 Master Plan is concerned not only with maintaining agriculture as a sustainable practice in the city, but that its maintenance be economically supported, and that in the medium term these agricultural enterprises can be inserted in trade routes and become economically sustainable. One of the previous policies that was not repeated was the idea that low-density housing and restricted agriculture could be done in environmental protection areas.

Complementary Bill No. 44/2021, the master plan that was debated, again, during Eduardo Paes' administration, but this time in the Social Democratic Party brings some very important changes, such as the example of the following excerpt.

XI – the stimulus to urban agriculture, small animal breeding and fishing, for their economic importance and autonomy and food security, as well as strengthening short production circuits, as established in the Milan Pact on Urban Food Policy, of which Rio de Janeiro Municipality is a signatory. (Rio de Janeiro, 2021b, n.p., Art. 7º).

The first difference is the specification of small animal breeding, which expands the possibilities of urban agriculture; before, the text spoke of agriculture and fishing, but not necessarily of animal breeding.

Recently, a series of small changes occurred in the text being discussed, one of them was the removal of the point above. When asked to the city hall's technical staff about this issue of animal breeding, the response was

The Plan has not yet been approved. This latest version, unless I am mistaken, does not speak specifically about poultry [i.e. small animals]. The guidelines and structuring actions of the PD's sectoral policies were discussed with municipal agencies and presented to civil society in two moments (from 2019 to 2021, with the Interlocutor Group, which covered various social segments that participated in the initial discussions at the invitation of the then Secretariat of Urbanism) and in 2021 by public call, expanding the range of entities and social movements that were interested in participating. Through the following link, what was agreed with the agencies in this report can be verified:

https://www.rio.rj.gov.br/documents/91237/c110a440-e14d-4672-8dfb-436f2a4d88f5.

In this report, which covers everything that was agreed with the agencies and compared with the Sustainability Plan, there is no mention of the word "animals", much less "poultry". As for the word "breeding", what appears is "Rescue, enable, increase and value agricultural activity and production, animal breeding and artisanal fishing, in a sustainable way and with respect for community relations and the environment." (Interview conducted by email on July 18, 2023, emphasis mine)

The second difference is the bet on creating short production circuits, an idea that has been much worked on recently within urban agriculture movements – such as the example of AUÊ! - Study Group on Urban Agriculture of UFMG, in which various works on the theme were published and various experiences in the RMBH and Metropolitan Collar were identified. Direct product sales can help overcome some problems found in agroecological production and commercialization.

Characteristics of agroecological production such as: off-season, production seasonality, local and/or regional varieties, etc., are being disregarded by the demands of large retail chains. Consequently (sic), a considerable portion of local knowledge and cultural diversity of family agriculture are being eroded and lost. On the other hand, autonomy in commercialization and direct sales to consumers can contribute significantly to stimulating internal changes in productive systems, favoring the conversion process of conventional family farmers to organic production. (Wuerges and Simon, 2007, p. 568).

The idea is that this approximation between producers and consumers can reinforce beneficial relations for both, pointed out by Fonseca, Almeida and Colnago (2009, p. 2601, such as):

- Exchange of knowledge, know-how and flavors between producers and consumers;

- Possibility of better exercising social control of organic qualities and guarantees of organic products identified by consumers due to producer-consumer involvement and support organizations (public, private or civil society);

- Fresh products with lower prices than in large retail chains due to direct producer-consumer sales;

- Over time, increase in customer loyalty.

The increase in importance of short circuits generates a cycle that begins in association, in the form of cooperativism, among producers who commercialize through direct sales, such as in fairs, generating approximation between producers and consumers. The increase in consumer confidence in producers is converted into income for producers, who can increasingly become autonomous and promote local biodiversity complexity and contribute to job generation and diversification of consumer diets. Finally, according to Costa (2021)

Some practices are also important for the production of healthy foods, in short circuits, bringing producers and consumers closer and contributing to food and nutritional security of the population. In these cases, access to land and quality water, among other elements, is paramount. (Costa, 2021, p. 151).

It is important to emphasize that the Master Plan project itself recognizes the importance of urban agriculture as a generator of income and food security[12].

The third and last difference is regarding the City Hall's adherence to the Milan Pact on Urban Food Policy. Through this commitment, signatory municipal governments demonstrate the intention to "review all existing urban policies, plans and regulations in order to encourage the establishment of equitable, resilient and sustainable food systems" (Pact, 2015[13]).

The evolution of one of the previously presented policies is the incentive for occupation of environmental protection areas with restricted agriculture and low-density housing.

III – Transition areas between areas subject to environmental protection and areas with controlled urban occupation: composed of areas with low density of land use and occupation, by agricultural activity and small animal breeding and which are destined to maintain urban-environmental balance.

[...] § 4º Other areas occupied with agricultural use or low-intensity small animal breeding, prioritarily of family agriculture and agroecology, with sustainable management, are considered areas of restriction to occupation, classified in the third level of protection, of transition areas between areas subject to environmental protection and areas with controlled urban occupation, for their environmental relevance and use and occupation compatible with maintaining the City's ecosystem services. (Rio De Janeiro, 2021b, n.p.).

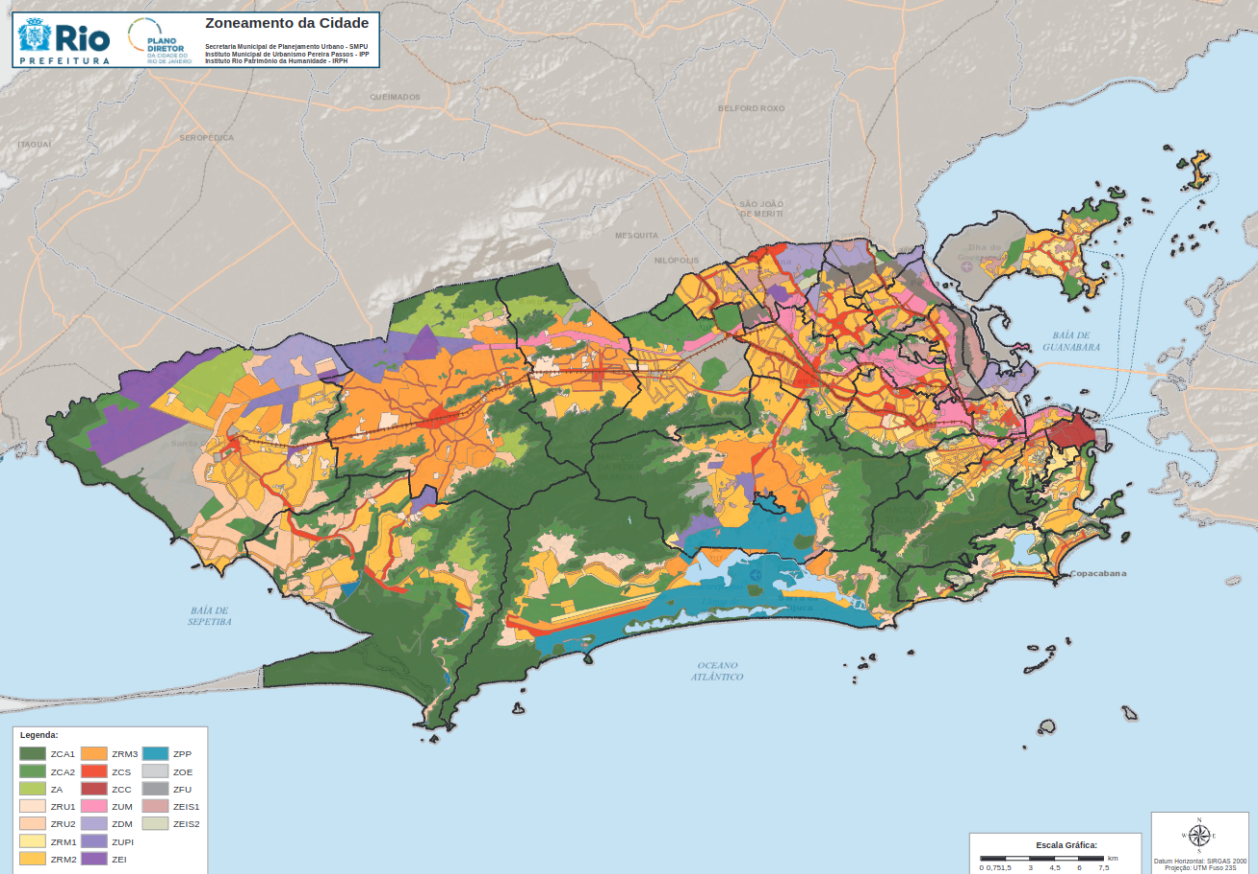

If in previous master plans urban agriculture always entered the macrozones of restriction of urban land use, in the current Plan it enters a specific macrozoning:

Art. 71. The Sustainable Use Macrozone is composed of areas of significant environmental and landscape value with low-density occupation, protected areas that admit low-impact occupation, transition areas between fully protected territory and consolidated urban areas and areas of significant environmental and landscape value endowed with potential for installation of sustainable use Conservation Units.

Art. 72. The priority guidelines for the Sustainable Use Macrozone are:

I – limit constructive densification and occupation intensity in order to promote a transition environment around protected areas;

II – promote the mixture of low-impact uses and low-intensity occupation, not generating trips and noise;

III – maintain and expand low-impact agricultural activity, especially that practiced:

a) by family agriculture;

b) by adopting Agroforestry Production Systems;

c) in the production of forest essences and seeds. (Rio de Janeiro, 2021b, n.p.).

Urban agriculture is used as a buffer between areas of more intense urbanization and environmental protection areas. There are, then, Agricultural Zones (ZAs) in this Master Plan, but all of them exist in this sense of being a buffer between environmental protection zones. These ZAs are defined as "II – Agricultural Zone – ZA: zone where agricultural or animal breeding activities prevail and those of support and complementation, compatible with each other;" (Rio de Janeiro, 2021b, n.p.).

Perhaps the most celebrated policy of this master plan project is the liberation of planting and care of small animals throughout the city, without restrictions of specific zones as seen in the 1970s plan.

Figure 2 - Proposed Zoning - Rio de Janeiro (2021)

Source: Urban Planning System (SiPlan, 2023)

In addition to municipal texts, urban agriculture also began to be stimulated by federal regulations, such as Ordinance No. 467/2018 and Decree No. 11,700/2023, which established guidelines for integrating agricultural practices into urban environments. Such changes dialogue with international commitments, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN's 2030 Agenda, which provide for specific actions to eradicate hunger, promote sustainable agriculture and build more inclusive and resilient cities.

Public Policies on Urban Agriculture

Research in the Official Gazettes of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, from 1969 to the present day, did not identify results prior to the 2000s for the keywords used (i.e., urban agriculture; family farming; gardens; community gardens; urban gardens). From the mid-2000s onwards, Rio de Janeiro witnessed the emergence of various actions aimed at encouraging and supporting urban and family agriculture. One of the first initiatives was the Carioca School of Urban Agriculture in 2005, under the Social Assistance Secretariat. The School played a fundamental role by offering technical assistance, specialized labor, and seeds to urban farmers, contributing to the development of more sustainable and inclusive agriculture in the city.

In 2007, the Community Gardens project, linked to the Carioca School of Family Agriculture[14], gained prominence by promoting the training of students interested in cultivation techniques and sustainable management. This project also aligned with the Pro-Youth Program, which found in the school a strategic partner to train potential young farmers.

To further expand the knowledge and training of farmers, the Model Farm was created in 2007, a space that offers courses and training to improve agricultural practices and management of rural properties in the region. The issue of food security gained prominence when the Food and Nutritional Security Council of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro (CONSEA/RJ) strengthened the Farmers' Network between 2009 and 2011. This action brought to light topics such as food security and climate change, while the community kitchen proved to be an essential tool for addressing food and nutritional challenges in communities. However, the Model Farm faced stigma due to its origin as a former shelter for homeless people and those displaced from risk areas.

The 2010s brought new achievements, such as the Carioca Circuit of Organic Fairs, which strengthened local commerce and the marketing of healthy products directly from producer to consumer.

A significant milestone was reached in 2019, when Law No. 6,691 was enacted, establishing the Policy for Supporting Urban and Peri-urban Agriculture in the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro. This policy was conceived as an integral part of agricultural, urban, and food and nutritional security policies, all based on sustainability principles.

Looking toward the future, the Multi-annual Plan 2022/2025 of the Rio de Janeiro City Hall provides for actions to train local farmers in marketing their products and assist in production flow. These measures aim to further strengthen the local economy and encourage the continued growth of urban and family agriculture.

In this context, the Municipal Producer Market of the West Zone, in Guaratiba, emerges as an important ally for the flow of farmers' production, connecting them to a broader and more diversified market.

It is important to note that several of the policies described here take place in the West Zone of the city, reinforcing the hypothesis that the focus of these policies shapes the region as agricultural. It is also interesting to note a development that initially focused more on farmer training policies and later shifted to focus more on policies that guarantee spaces for commodity circulation and the creation of short circuits.

Final Considerations

The historical and normative analysis of zoning and urban land use policies in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro evidences a progressive process of recognition and valorization of urban agriculture as a strategic component of territorial planning and the promotion of socio-environmental sustainability. From Municipal Decree No. 322/1976 to Complementary Bill No. 44/2021, a trajectory of expanding the scope of public policies is observed, with growing emphasis on integrating urban agriculture into urban dynamics and promoting food security, solidarity economy, and spatial justice.

The implementation of specific zones, the incentive to adopt agroecological practices, the creation of public facilities aimed at agricultural production, and the institutionalization of policies such as Law No. 6,691/2019 reflect not only legislative progress but also a paradigm shift in how urban territory is conceived and managed. The recent emphasis on creating markets, fairs, and short marketing circuits indicates a relevant inflection in the public agenda, focused on valuing producer subjects and strengthening local economies.

This convergence between urban planning instruments and urban agriculture policies evidences a trend toward greater alignment between existing practices and institutional norms, signaling an openness to the complexity of urban realities and the need for more inclusive and participatory approaches. This process is also in line with international commitments assumed by Brazil, such as the UN's 2030 Agenda, which reinforces the role of municipalities in promoting resilient, sustainable, and socially just cities.

As a possibility for future work, it is considered relevant to deepen the investigation by listening to technicians, public managers, and urban farmers, in order to capture their perceptions about the effectiveness of current policies and the challenges faced in their implementation. Additionally, the analysis of the concrete impacts of Complementary Bill No. 44/2021 on Carioca urban agriculture.

References

BRAZIL. [Constitution (1988)]. Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil. Brasília, DF: Supreme Federal Court, 2023. 264 p. Available at: https://www.stf.jus.br/arquivo/cms/legislacaoConstituicao/anexo/CF.pdf. Accessed on: Aug. 11, 2023.

BRAZIL. Federal Law on Land Parceling No. 6766, dated December 19, 1979. Provides on organic agriculture and other provisions. Official Gazette of the Union: Brasília, DF, Dec. 20, 1979.

BRAZIL. City Statute. Law No. 10,257, dated July 10, 2001. Regulates Articles 182 and 183 of the Federal Constitution, establishes general guidelines for urban policy, and other provisions. Official Gazette of the Union: Brasília, DF, Jul. 11, 2001.

BRAZIL. Law No. 10,831, dated December 23, 2003. Provides on Urban Land Parceling and other provisions. Official Gazette of the Union: Section 1, Brasília, DF, p. 8, Dec. 24, 2003.

BRAZIL. Ministry of Health. Health Care Secretariat. Primary Care Department. Food Guide for the Brazilian Population. 2nd ed., 1st reprint. Brasília, DF: Ministry of Health, 2014. 156 p.

COSTA, Geraldo Magela et al. Planos Diretores e Políticas Territoriais: Reflexões a partir de transformações no Vetor Norte de expansão da RMBH. In: Seminário sobre a Economia Mineira, 14., 2010, Diamantina. Anais [...]. Belo Horizonte: Cedeplar UFMG, 2010. N.p.

COSTA, Heloisa S. M.; CAMPANTE, Ana Lúcia Goyatá; ARAÚJO, Rogério P. Z. A dimensão ambiental nos planos diretores de municípios brasileiros: um olhar panorâmico sobre a experiência recente. In: BRASIL. Ministério das Cidades. Os planos diretores municipais Pós-Estatuto da Cidade: balanço crítico e perspectivas. Rio de Janeiro: Letra Capital, 2011. p. 173-217.

FONSECA, Maria Fernanda de Albuquerque Costa; ALMEIDA, Lucia Helena Maria; COLNAGO, Nathalia Fendeler. Características, estratégias, gargalos, limites e desafios dos circuitos curtos de comercialização de produtos orgânicos no Rio de Janeiro: as feiras. Revista Brasileira de Agroecologia, Rio de Janeiro, v. 4, n. 2, p. 2599-2602, nov. 2009.

MONTE-MÓR, Roberto Luís. Planejamento urbano no Brasil: emergência e consolidação. Revista Eletrônica de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, [S. l.], v. 1, n. 1, p. 71-96, 2007.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Municipality). Decree No. 322 of March 3, 1976. Approves the Zoning Regulations of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro. Official Gazette of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro: Rio de Janeiro, Mar. 4, 1976.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Municipality). Law No. 6,691, dated December 19, 2019. Provides on the Municipal Policy for Support of Urban and Peri-urban Agriculture. Official Gazette of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro: Rio de Janeiro, Dec. 20, 2019.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Municipality). Madureira Park will have the largest urban garden in the world. Rio de Janeiro City Hall, Rio de Janeiro, Sep. 2021a. Environment – News. Available at: https://prefeitura.rio/meio-ambiente/parque-madureira-tera-a-maior-horta-urbana-do-mundo/. Accessed on: Oct. 29, 2021.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Municipality). Urban and Sustainable Development Master Plan of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro. Complementary Law No. 111, dated February 1, 2011a. Provides on the Urban and Environmental Policy of the Municipality, establishes the Urban and Sustainable Development Master Plan of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, and other provisions. Official Gazette of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro: Rio de Janeiro, Feb. 2, 2011.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Municipality). Ten-Year Master Plan of the City of Rio de Janeiro. Complementary Law No. 16 of June 4, 1992. Provides on the Urban Policy of the Municipality, establishes the Ten-Year Master Plan of the City of Rio de Janeiro, and other provisions. Official Gazette of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro: Rio de Janeiro, Jun. 5, 1992.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Municipality). Master Plan: project foresees increase of construction potential in several areas of the North Zone. Municipal Chamber of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Jun. 2022a. News. Available at: http://www.camara.rio/comunicacao/noticias/1139-plano-diretor-projeto-preve-aumento-do-potencial-construtivo-em-diversas-areas-da-zona-norte. Accessed on: Aug. 11, 2023.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Municipality). Executive Power. Official Gazette of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, year 21, no. 185, Dec. 18, 2007. p. 29.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Municipality). Executive Power. Official Gazette of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, year 21, no. 186, Dec. 19, 2007. p. 41.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Municipality). Executive Power. Official Gazette of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, year 24, no. 47, May 25, 2010. p. 43.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Municipality). Executive Power. Official Gazette of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, year 25, no. 51, May 26, 2011. p. 82.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Municipality). Complementary Bill No. 44 of 2021. Establishes the revision of the Urban Sustainable Development Master Plan. Rio de Janeiro: SiPlan: CTPD, [submitted to the Municipal Chamber], Sep. 2021b. Available at: https://planodiretor-pcrj.hub.arcgis.com/. Accessed on: Aug. 11, 2023.

SANTOS, R. F. Situação atual e perspectivas de desenvolvimento da Área de Planejamento 3 da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. 2012. 103 p. Dissertation (Master in Civil Engineering) – Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2012.

SILVA, Bianca Mariquito Naime. O Planejamento de áreas rurais: um estudo sobre municípios da Região Metropolitana de Belo Horizonte. 2012. Undergraduate Final Paper (Geography) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2012.

WUERGES, Edson Walmor; SIMON, Álvaro Afonso. Feiras-Livres como uma forma de popularizar a produção e o consumo de hortifrutigranjeiros produzidos com base na agroecologia. Revista Brasileira de Agroecologia, Rio de Janeiro, v. 2, n. 2, p. 567-570, out. 2007. Paper presented at the V Congresso Brasileiro de Agroecologia, 2007, Guarapari.

About the Authors

Yago Evangelista Tavares de Souza holds a bachelor's degree in Geography from Universidade Federal Fluminense and a master's degree, also in Geography, from Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Currently pursuing his doctorate at UFF, he investigates forced displacement and interpersonal networks that help in the adaptation and resilience of people in displacement situations, analyzing how these networks can influence urban planning and public policies aimed at those affected.

Heloisa Soares de Moura Costa holds a bachelor's degree in Architecture and Urban Planning from Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (1976), a master's degree M Phil in Urban Planning - Architectural Association (1983), a doctorate in Demography from Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (1995), and a post-doctorate from the Geography Department at University of California, Berkeley (1997/8). She is currently a full professor in the Geography Department at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, with main research areas including: urban planning, urban geography, public policies, and socio-environmental implications. She was coordinator of the Population and Environment Working Group of the Brazilian Association of Population Studies (2000-2002) and president of the National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in Urban and Regional Planning (2003-2005). She participates in editorial boards of journals in the field, including Revista Geografias (UFMG). Executive Editor of Revista da UFMG. She was a member of the Municipal Councils of Urban Policy and Housing of Belo Horizonte. CNPq researcher. She was a representative of the PUR area (2006-2009) and alternate for the Demography Area (2011-2014) in the Human and Applied Social Sciences Advisory Committee of CNPq. She coordinates the following Research Groups registered in the CNPq Directory: Spatial and socio-environmental processes: urban and regional analysis and population dynamics; and AUÊ! - Urban Agriculture Studies Group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.E.T.S., H.S.M.C., methodology, Y.E.T.S., H.S.M.C., software, Y.E.T.S., H.S.M.C., validation, Y.E.T.S., H.S.M.C., formal analysis, Y.E.T.S., H.S.M.C., investigation, Y.E.T.S., H.S.M.C., resources, Y.E.T.S., H.S.M.C., data curation, Y.E.T.S., H.S.M.C., writing—original draft preparation, Y.E.T.S., H.S.M.C., writing—review and editing, Y.E.T.S., H.S.M.C., visualization, Y.E.T.S., H.S.M.C.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

About Coleção Estudos Cariocas

Coleção Estudos Cariocas (ISSN 1984-7203) is a publication dedicated to studies and research on the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, affiliated with the Pereira Passos Institute (IPP) of the Rio de Janeiro City Hall.

Its objective is to disseminate technical and scientific production on topics related to the city of Rio de Janeiro, as well as its metropolitan connections and its role in regional, national, and international contexts. The collection is open to all researchers (whether municipal employees or not) and covers a wide range of fields — provided they partially or fully address the spatial scope of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Articles must also align with the Institute’s objectives, which are:

- to promote and coordinate public intervention in the city’s urban space;

- to provide and integrate the activities of the city’s geographic, cartographic, monographic, and statistical information systems;

- to support the establishment of basic guidelines for the city’s socioeconomic development.

Special emphasis will be given to the articulation of the articles with the city's economic development proposal. Thus, it is expected that the multidisciplinary articles submitted to the journal will address the urban development needs of Rio de Janeiro.

[1] "Regulation of the urbanization process aiming at environmental protection through pollution control, preservation of natural resources, and recovery of destroyed elements" (Draft Urban Development Bill of 1977, p. 1)

[2] "III-B – along running and still waters, the non-buildable buffer zones shall comply with the municipal or district law that approves the territorial planning instrument and defines and regulates the width of riparian buffer strips in consolidated urban areas, pursuant to Law No. 12,651 of May 25, 2012, with the mandatory reservation of a non-buildable strip for each riverbank segment, as indicated in a socio-environmental assessment carried out by the Municipality; (Included by Law No. 14,285 of 2021) [...] § 3 – If necessary, the reservation of a non-buildable strip along pipelines shall be required within the scope of the respective environmental licensing process, in accordance with criteria and parameters that ensure public safety and environmental protection, as established by the relevant technical regulations. (Included by Law No. 10,932 of 2004)" (BRAZIL, 1979).

[3] "Land Use Control in order to avoid: [...] IX – protection, preservation, and recovery of the environment" (Preliminary Draft of the Urban Development Law, 1982, p. 165).

[4] "Art. 14. In promoting urban development, the Federal Government shall: [...] g) protect the environment" (Preliminary Draft of the Urban Development Law, 1982, p. 167).

[5] "Art. 2 The urban policy aims to guide the full development of the social functions of the city and urban property, according to the following general guidelines:

I – the guarantee of the right to sustainable cities, understood as the right to urban land, housing, environmental sanitation, urban infrastructure, transportation and public services, employment, and leisure, for present and future generations." (Law No. 10.257, of July 10, 2001, p. 1)

[6] "VII – integration and complementarity between urban and rural activities, considering the socioeconomic development of the Municipality and the territory under its area of influence." (Law No. 10.257, of July 10, 2001, p. 3)

[7] "XV – guarantee of spaces for the development of agricultural activities, especially for the production of fruits, vegetables, and small livestock." (Rio de Janeiro, 1992, n.p.)

[8] "Art. 206. Priority programs of the economic, scientific and technological development policy shall include:

[…] III – a program to promote agricultural and fishing activities." (Rio de Janeiro, 1992, n.p.)

[9] “By ‘fragile lowland areas’, one should understand water recharge zones, floodplains, and other similar features related to the site’s hydrology.”

[10] It is hypothesized that the two main motivations for classifying an entire territory as urban are: a) to increase tax revenue; or b) to enable greater municipal control over the specific territory for future land subdivisions. This is a hypothesis that needs to be further explored by future research.

[11] It would be important for future research to investigate whether this experience is replicated in other cities. If so, it becomes a relevant factor in the formulation of public policies at both the federal and municipal levels. Since legislation has already changed, it is worth considering whether many other municipalities share this experience, though this footnote may no longer be necessary.

[12] “VIII – promotion of agricultural activities, small-scale livestock farming, and fishing, as a means to ensure food security in the City and to generate employment and income.” (RIO DE JANEIRO, 2021b, n.p.).

[13] MILAN Urban Food Policy Pact. Milan Urban Food Policy Pact. 2015. Available at: https://rio30.rio/parceiro/pacto-de-milao-para-politica-de-alimentacao-urbana/. Accessed on: Aug. 11, 2023.

[14] Although it is the same institution, it appears several times under different names, sometimes as the School of Urban Agriculture and other times as the School of Family Agriculture.