Volume 13 Issue 1 *Corresponding author ivokory@gmail.com Submitted 8 Apr 2025 Accepted 29 Apr 2025 Published 16 May 2025 Citation KORYTOWSKI, I.. The mystery of the oratory at the top of Morro da Providência, in Rio de Janeiro. Coleção Estudos Cariocas, v. 13, n. 1, 2025.

DOI: 10.71256/19847203.13.1.139.2025 The article was originally submitted in PORTUGUESE. Translations into other languages were reviewed and validated by the authors and the editorial team. Nevertheless, for the most accurate representation of the subject matter, readers are encouraged to consult the article in its original language.

| The mystery of the oratory at the top of Morro da Providência, in Rio de Janeiro O mistério do oratório do alto do Morro da Providência, no Rio de Janeiro El misterio del oratorio en la cima del Morro da Providência, en Río de Janeiro Ivo Korytowski¹ 1Independent Researcher, ORCID 0009-0000-5201-2052, ivokory@gmail.com

AbstractThe article seeks to unravel the mystery of the oratory at the top of Morro da Providência, in the waterfront of Rio de Janeiro, supposedly built to celebrate the arrival of the 20th century, but which already appears in photographs and engravings from previous times. To do this, it will go back to the invasion of Rio de Janeiro in 1711 and the subsequent attempt to fortify the city, looking for evidence that the aforementioned oratory was not built from scratch, but took advantage of an old observation tower that pre-existed in that location. Keywords: Morro da Providência, French invasion in 1711, fortification of Rio de Janeiro.

ResumoO artigo procura desvendar o mistério do oratório do alto do Morro da Providência, na Zona Portuária do Rio de Janeiro, supostamente erguido para comemorar a chegada do século XX, mas que já aparece em fotografias e gravuras de épocas anteriores. Para isso, retrocederá à invasão do Rio de Janeiro de 1711 e à subsequente tentativa de fortificar a cidade, buscando evidências de que o referido oratório não foi construído do zero, mas utilizou-se de uma antiga atalaia de observação preexistente naquele local. Palavras-chave: Morro da Providência, invasão francesa de 1711, fortificação do Rio de Janeiro.

ResumenEl artículo busca desentrañar el misterio del oratorio en lo alto del Morro da Providência, en la Zona Portuaria de Río de Janeiro, supuestamente construido para celebrar la llegada del siglo XX, pero que ya aparece en fotografías y grabados de épocas anteriores. Para ello, se remontará a la invasión de Río de Janeiro en 1711 y al posterior intento de fortificar la ciudad, buscando evidencia de que el mencionado oratorio no fué construído desde cero, sino que aprovechó una antigua torre de observación que preexistía en esse lugar. Palabras clave: Morro da Providencia, invasión francesa en 1711, fortificación de Río de Janeiro.

|

Introduction

At the top of Providência Hill stands an old oratory that, according to urban legend, was built by soldiers returning from the War of Canudos who "occupied" the hill and created Rio de Janeiro’s "first" favela. The very term "favela" was brought from Canudos, where it named a plant and a hill, as seen in Os Sertões (Rebellion in the Backlands). About the plant, Euclides da Cunha writes:

As favelas, still anonymous in science — ignored by scholars, overly familiar to the tabaréus — perhaps a future genus cauterium of legumes, have, in their leaves with elongated cells and villosities, remarkable adaptations for condensation, absorption, and defense. (Cunha, 1902, p. 18)

About the hill, the author writes:

All finally trace an elliptical curve closed to the south by a hill, that of Favela, around a wide undulating plain where the settlement of Canudos stood [...] He climbed to the top of Favela. He turned his gaze around to grasp the entirety of the land in one glance. [...] From the top of Favela, if the Sun shot vertically and the stagnant atmosphere immobilized the surrounding nature, focusing on the open fields afar, the ground became indistinguishable. (Cunha, 1902, p. 11)

Though population density increased significantly with the soldiers’ occupation, Providência Hill was not entirely uninhabited before their arrival. For example, the Correio Mercantil of June 21, 1856, published on its front page:

We are asked to draw the authorities’ attention to the lack of cleanliness on Silva Manoel Street [now André Cavalcanti] and on Providência Hill, where many people reside, and where there is neither lighting, nor water, nor sanitation, nor policing. (NOTÍCIAS…, 1856, p. 1)

And while the occupation of Providência Hill by soldiers spawned the first major favela in the modern sense (though more recently the term "community" is preferred), technically a "small favela" already existed on Santo Antônio Hill by the late 19th century. Luís Edmundo recounts this in O Rio de Janeiro do meu Tempo (The Rio de Janeiro of My Time):

In Santo Antônio, a poor hill despite its central location in the city, the dwellings are mostly improvised, made of scraps and rags, as ragged and sorrowful as their inhabitants.

Here live beggars, the genuine ones, when not settled in the lodgings of Misericórdia Street, capoeiras, hustlers, vagrants of all sorts: women without family support, elderly who can no longer work, children, castoffs among able-bodied people, yet, worse still, without work or aid, true outcasts of fortune, forgotten by God...

The number of these latter swarms the slope as one ascends: some lying face-down on the grass, others leaning against the doorways of squalid homes, a cigarette stub on their lips, their melancholic gaze lost in the smiling glory of the landscape — men with nothing to do and no work to find. (Edmundo, 2003, p. 147)

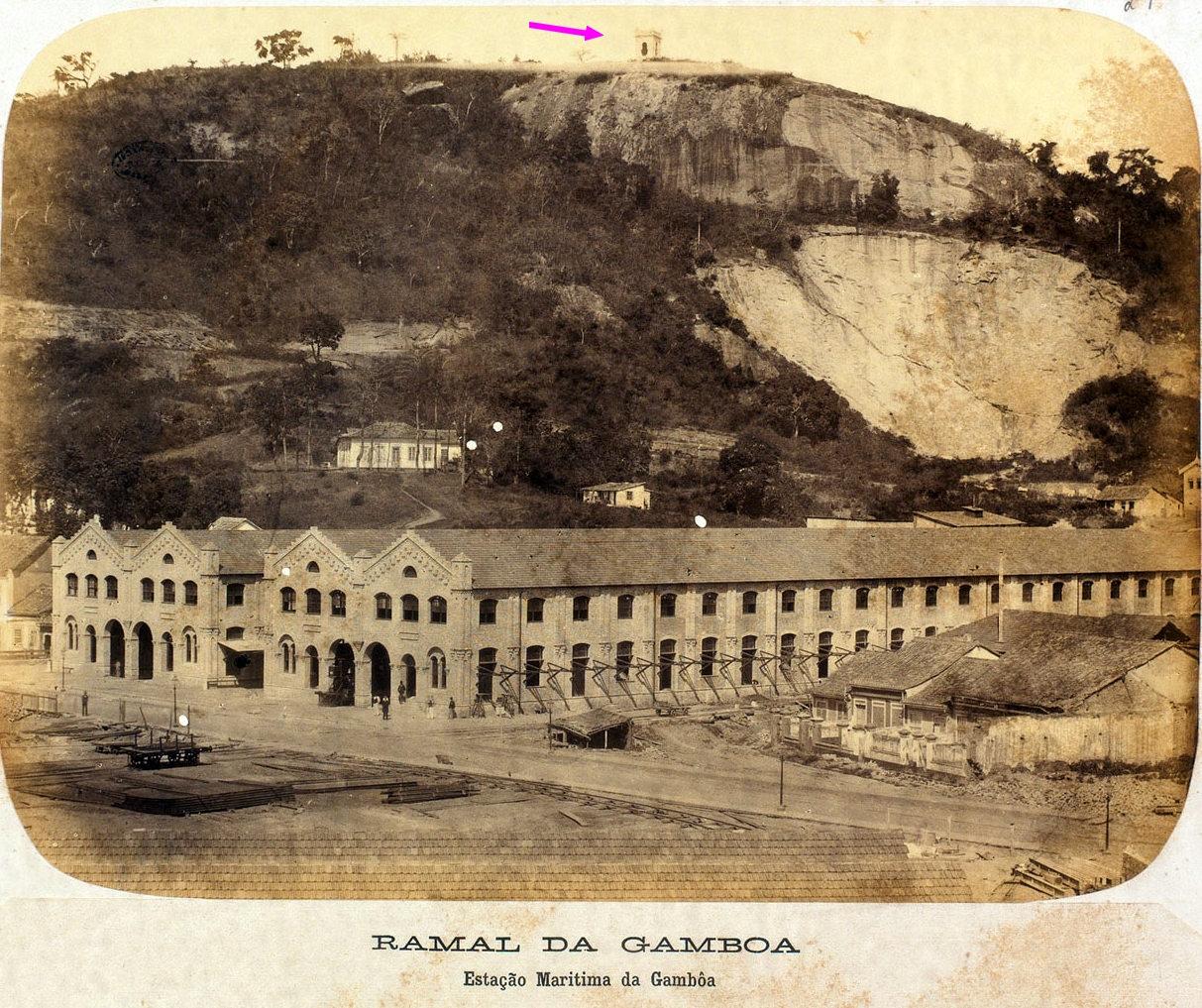

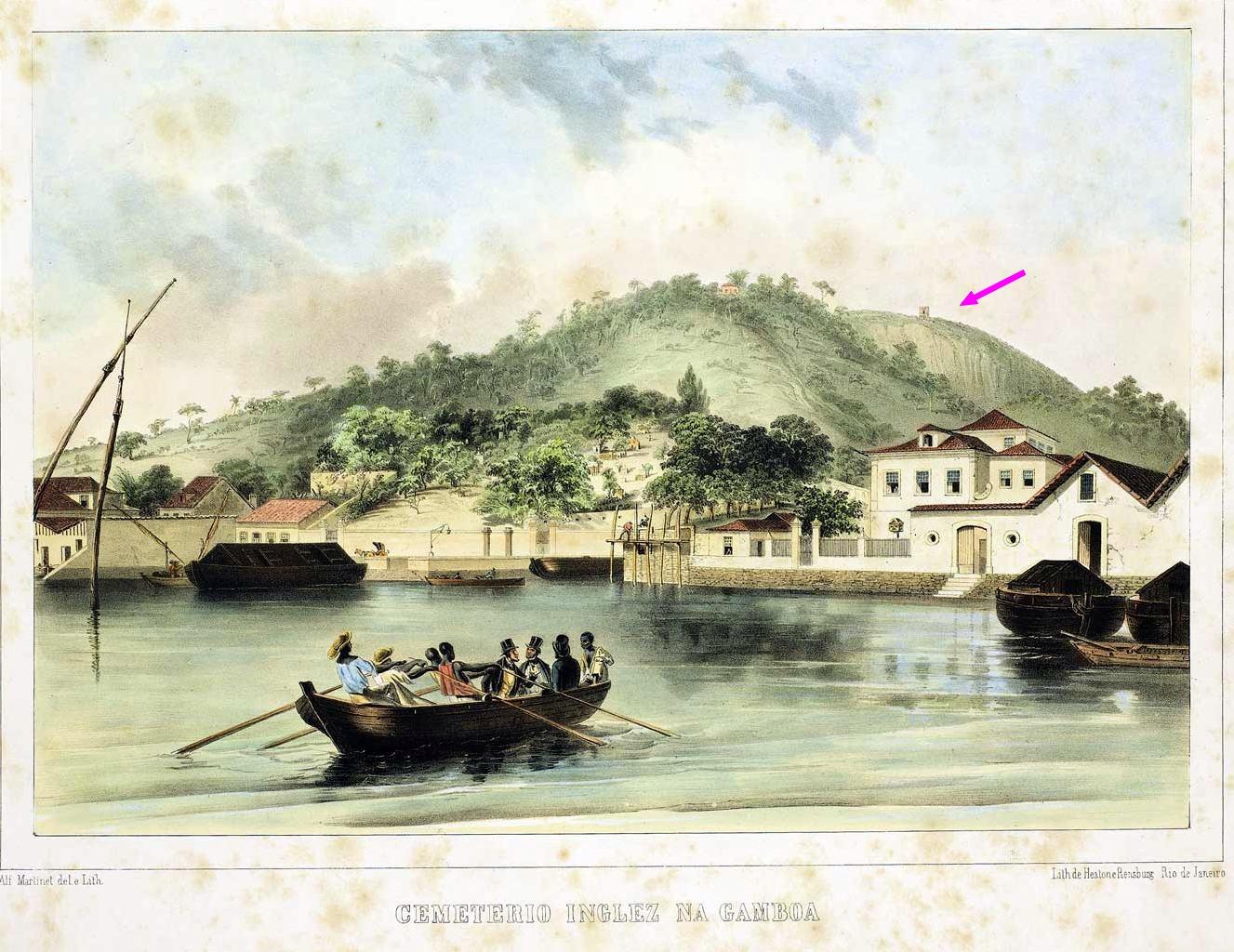

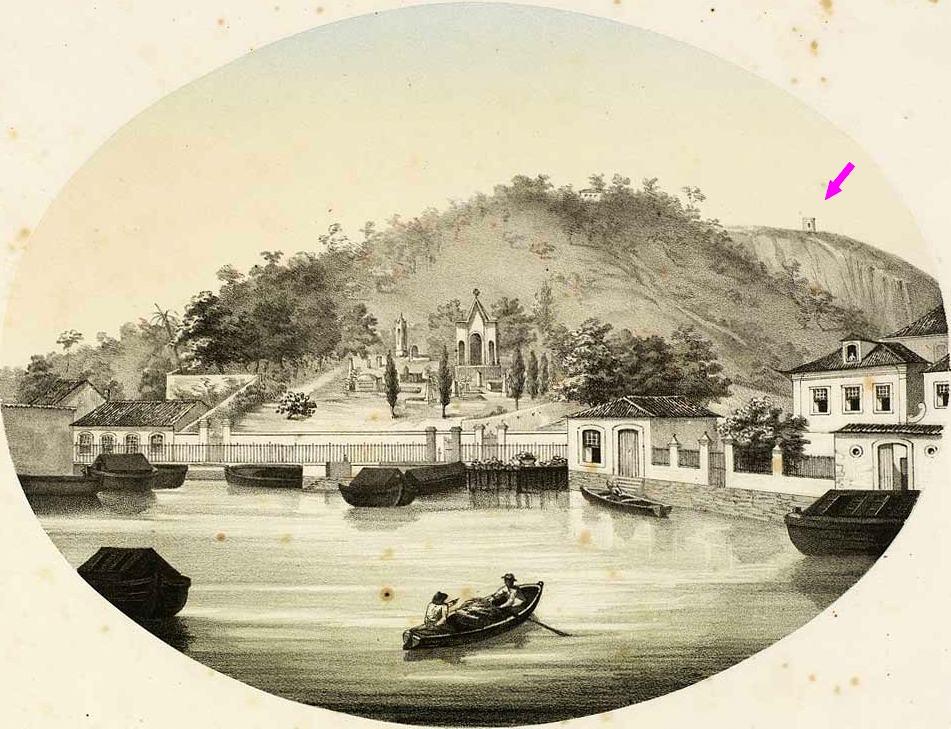

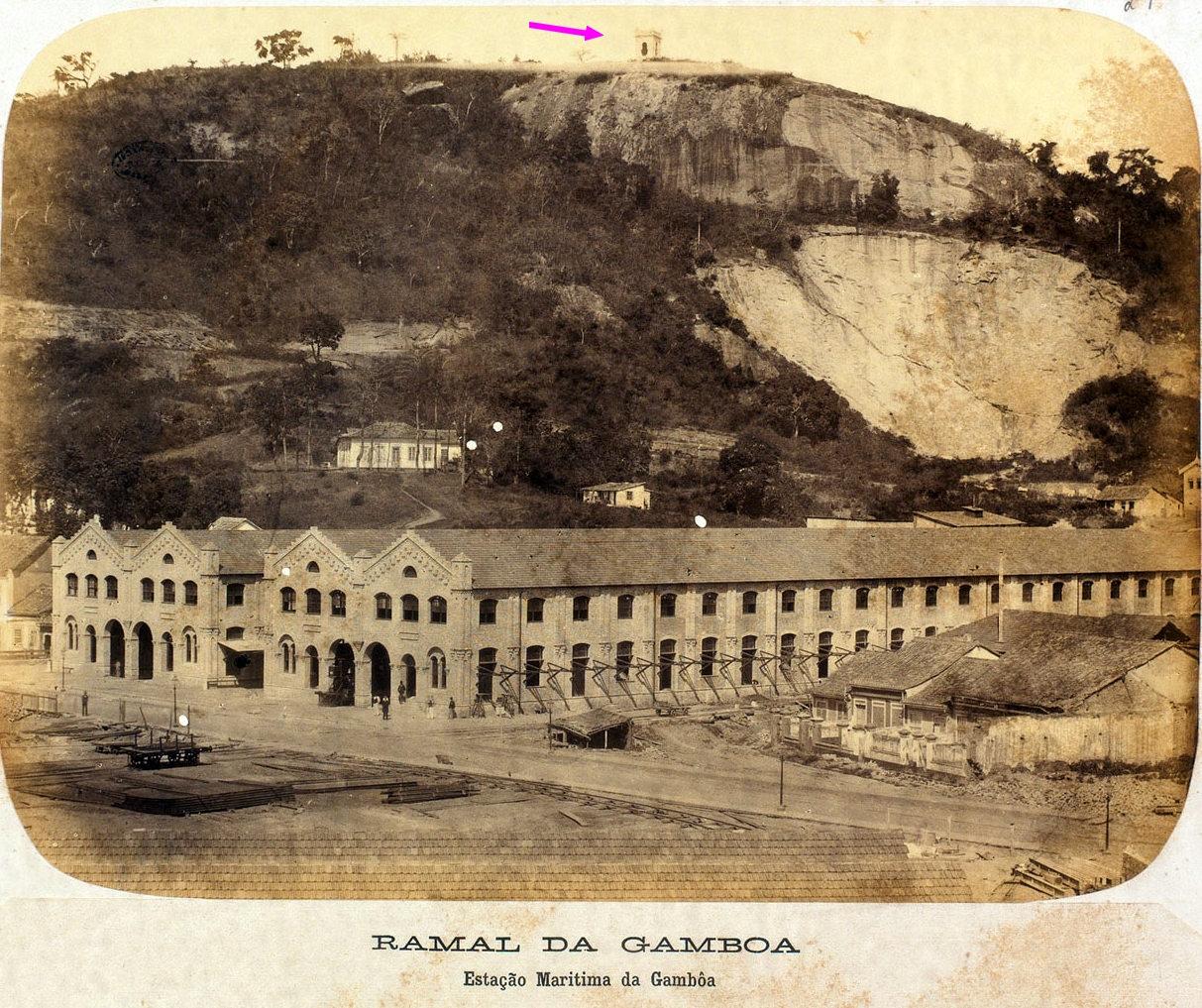

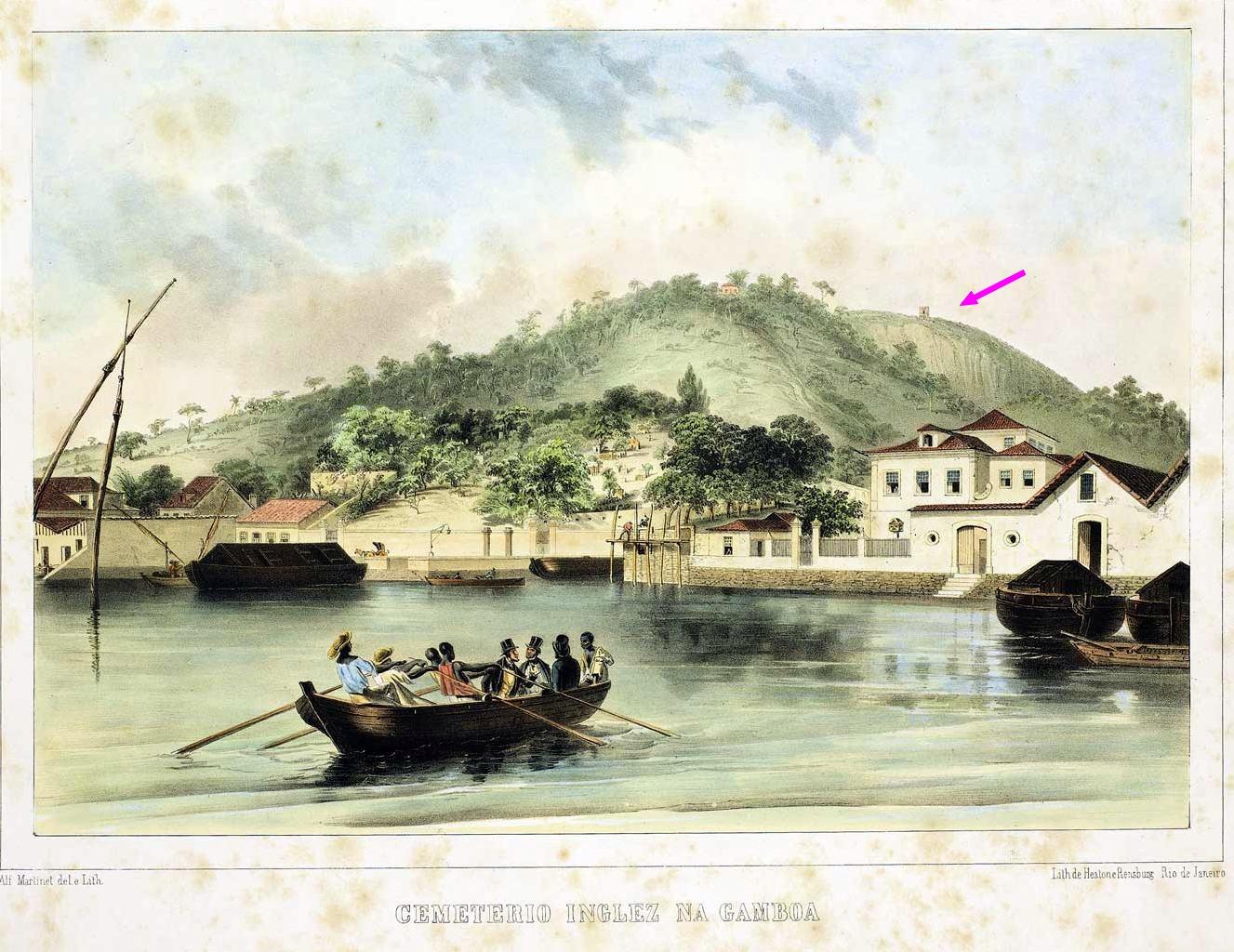

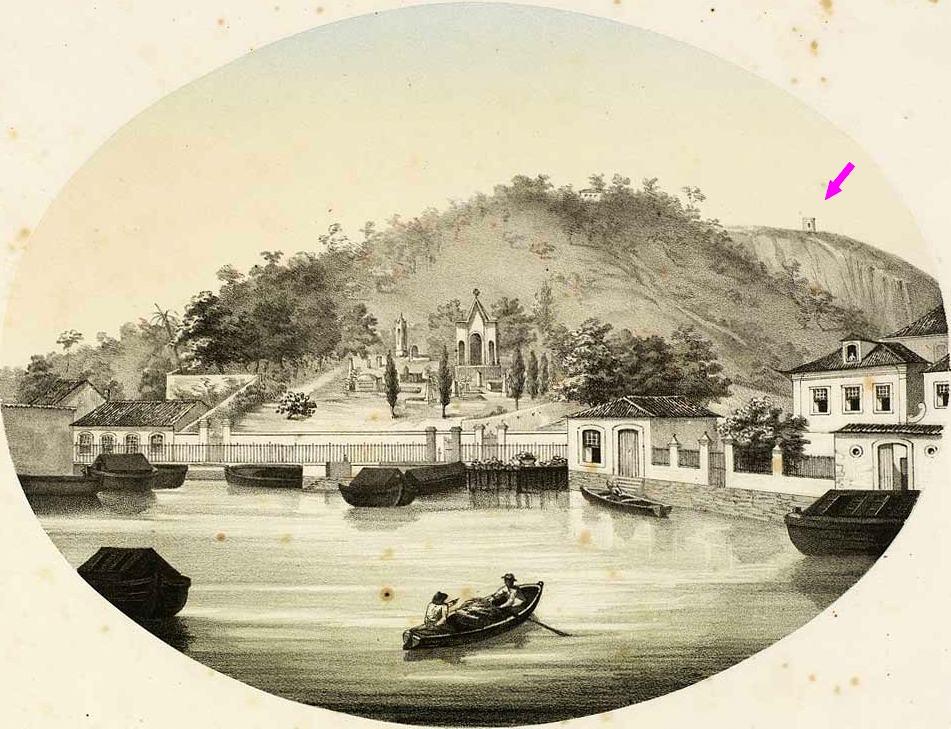

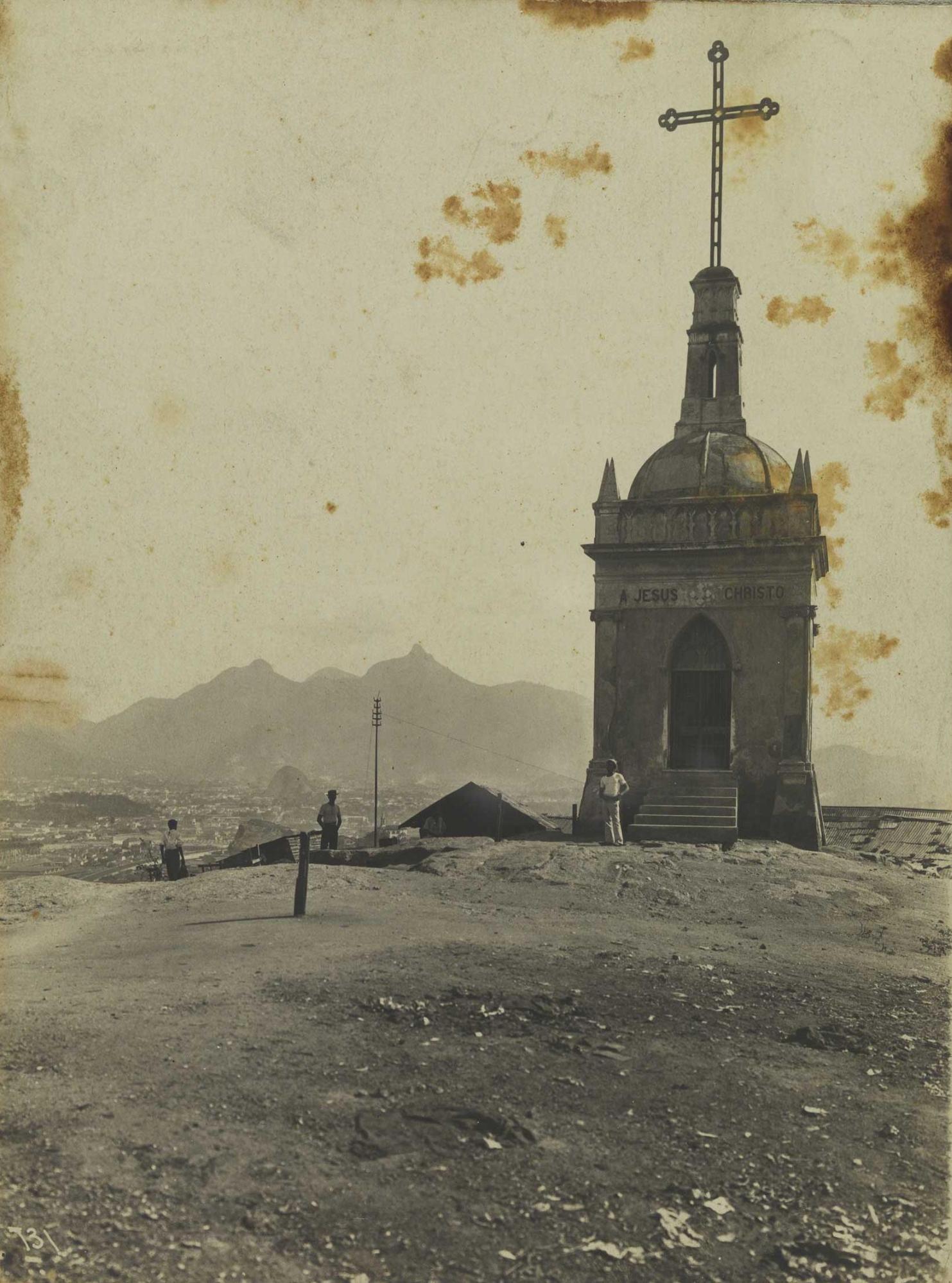

As for the "Oratory of Providência Hill," which, according to the Guide to Rio’s Cultural Heritage: Listed Sites published by the Rio de Janeiro City Hall in 2014, was "erected in 1901" (emphasis ours) and "reveals stylistic typography akin to the bell towers of Jesuit religious buildings," it already appears in an 1881 photograph (the War of Canudos would begin fifteen years later) and in engravings from 1847 and circa 1860.

Figure 1: Photo 29 from the album Collection of 44 Photographic Views of the Dom Pedro II Railway, 1881.

Source: Digital National Library.

Figure 2: Alfred Martinet, “English Cemetery,” engraving 7 from O Brasil pitoresco, histórico e monumental (Picturesque, Historical, and Monumental Brazil). Rio de Janeiro: Typ. Universal de Laemmert, 1847.

Source: Digital National Library.

Figure 3: Sebastien Auguste Sisson, “English Cemetery,” chromolithograph 7 from Álbum do Rio de Janeiro Moderno (Album of Modern Rio de Janeiro). Rio de Janeiro: S. A. Sisson, circa 1860.

Source: Digital National Library.

To unravel the mystery of the "1901" oratory, which makes its ghostly appearance in images from decades prior, we will first trace the history of Providência Hill. Next, we will address the city’s fortification after the Duguay-Trouin invasion of 1711. Finally, drawing on this information, we will argue that the oratory was originally an abandoned observation watchtower.

Outline of a History of Providência Hill

The historian seeking to probe the history of Providência Hill and unravel the mystery of the oratory must be familiar with its various names across maps from different eras.

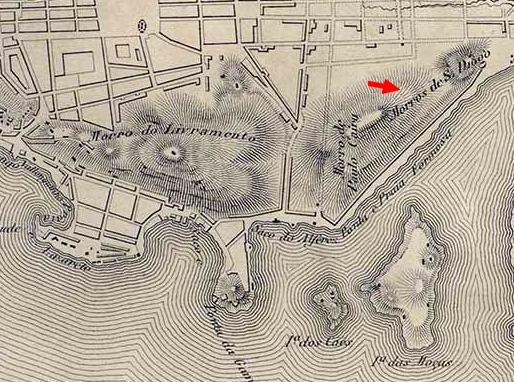

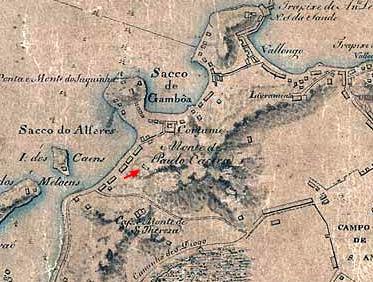

In some old maps (such as the one below), Providência Hill is not distinguished from Livramento Hill. Geographically speaking, Providência is not a separate hill but rather a "knob" at the southwestern tip of Livramento Hill. This is evident in the fact that Barroso Slope, which ascends the southern face of Livramento Hill, continues upward via a staircase to Providência Hill.

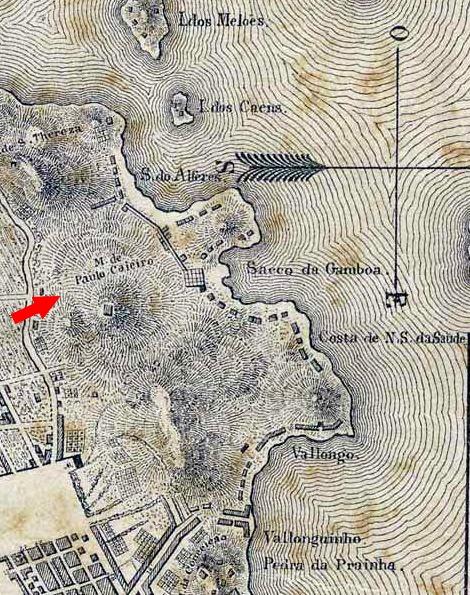

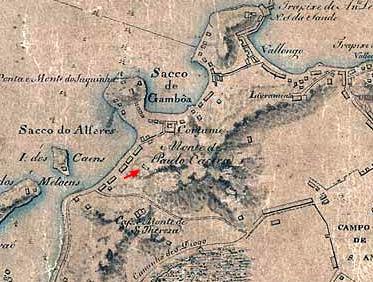

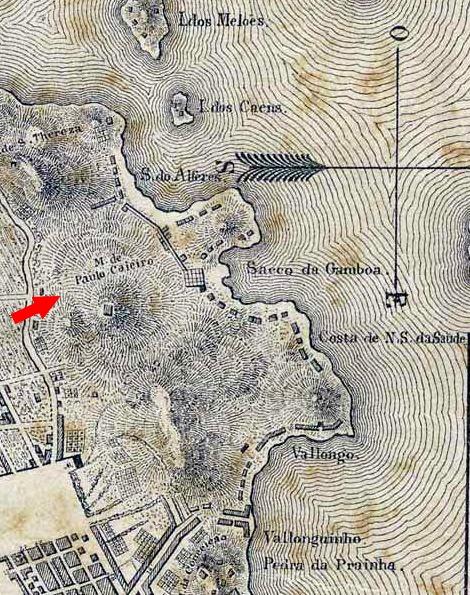

Figure 4: Detail from A Capital do Brasil (The Capital of Brazil), an 1831 map of Rio de Janeiro where Providência Hill is an extension of Livramento Hill.

Source: Digital National Library.

Figure 5: Staircase on Barroso Slope leading to Providência Hill in 2016, then painted pink and featuring lyrics from Raul Seixas’ song Aluga-se (“We won’t pay anything…”).

Source: Personal Archive.

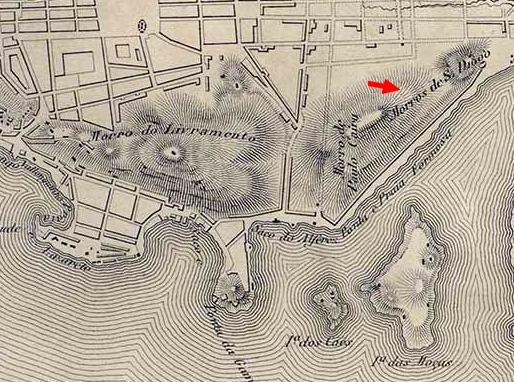

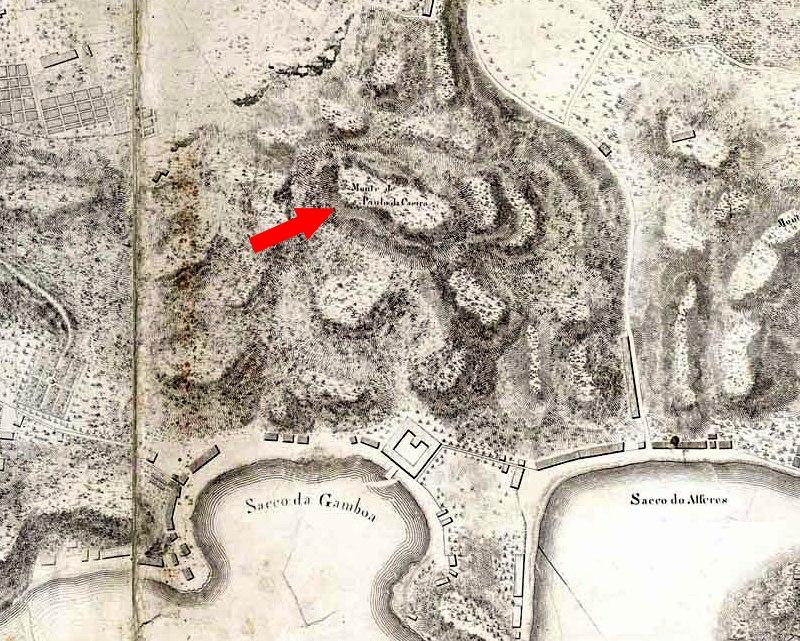

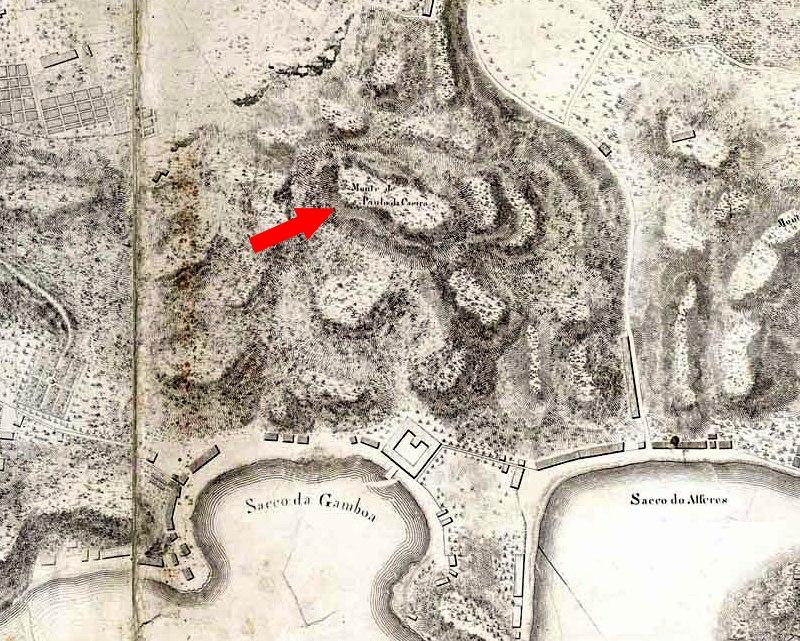

In the Planta da Cidade de S. Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro, levantada por ordem de S. A. R. Príncipe Regente Nosso Senhor no ano de 1808 (Map of the City of Saint Sebastian of Rio de Janeiro, Surveyed by Order of H.R.H. the Prince Regent in the Year 1808), published by Impressão Régia in 1812, Providência Hill is called Morro de Paulo Caieiro. A variant of this name found on a 1796 map is Monte de Paulo Caeira, and on an 1812 map, Monte de Paulo da Caeira (emphasis ours; this name will resurface later). The similarity to Morro de Paulo Cairu, which once designated the current Morro do Pinto, may cause confusion.

Figure 6: Detail from the Planta da Cidade de S. Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro... 1808, where Providência Hill is labeled Morro de Paulo Caieiro. Note the structure marked by a small square below the hill’s name, to which we will return later.

Source: Digital National Library.

The southern tip of Providência Hill, later "consumed" by quarrying, was called Morro da Formiga (Ant Hill) in the 19th century. During the turn of the 20th century, Providência Hill was popularly referred to as Morro da Favela.

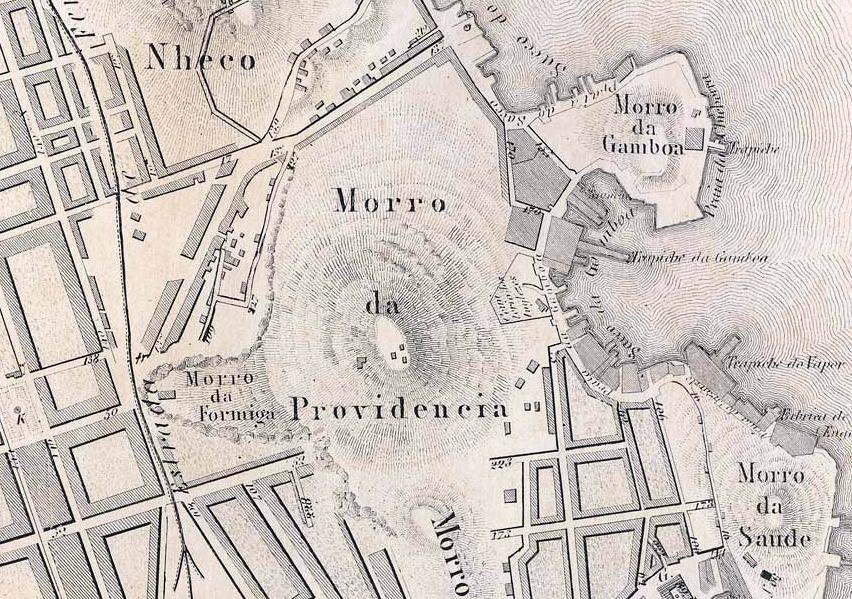

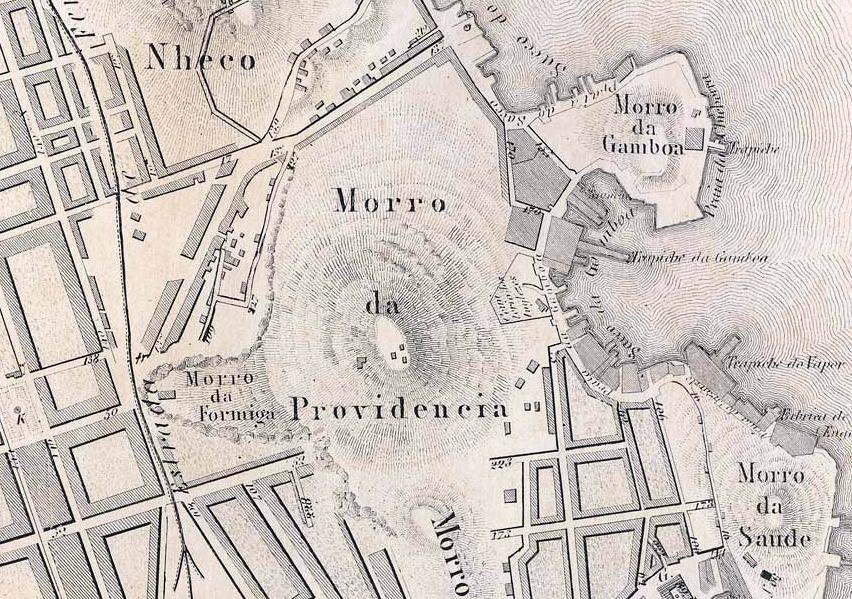

Figure 7: Detail from the Planta da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro Organizada no Arquivo Militar (Map of Rio de Janeiro Organized by the Military Archive) of 1858, where the southern slope of Providência Hill (left on the map) is labeled Morro da Formiga.

Source: Digital National Library.

2.1 Invasões francesas da década de 1710

Providência Hill enters history with the French invasion of 1711. The invasion was ostensibly to avenge Duclerc’s[1] defeat and free French prisoners from the prior year’s failed invasion, though a secondary motive was to seize Rio de Janeiro’s wealth, described by Louis Chancel de Lagrange[2] as:

A rather opulent Brazilian city [...], one of the richest in the world [...], both due to its proximity to gold mines and the Portuguese trade fleets that annually bring the most valuable European goods. Moreover, English and Dutch ships returning from the East Indies make it a mandatory stop, unloading their precious oriental cargoes. (Lagrange, 1967, pp. 51, 52, 56)

The entrance to Guanabara Bay was relatively narrow, with a “width roughly equal to the range of a cannon shot, with central rocks making access difficult via two channels defended by two formidable fortresses” (Lagrange, 1967, p. 56).

On the Rio side, Fort São João was armed with 18 cannons; on the Praia Grande (now Niterói) side, Fort Santa Cruz was perched on a promontory with dual rock-carved fortifications, deemed impregnable by the Portuguese and armed with "46 gun ports" (Lagrange, 1967, p. 56). The previous year, Duclerc, blocked by cannon fire from entering the bay, attempted a surprise maneuver: landing at Guaratiba Cove on the Atlantic coast, far from the city center, crossing the then-"backlands," and invading by land—yet he was defeated by soldiers and civilians. Duguay-Trouin, however, boldly forced entry into the bay under thick fog and favorable easterly winds, so that "the enemy only noticed our presence too late" (Lagrange, 1967, p. 54). He captured strategic Ilha das Cobras and, the next dawn, followed his predecessor’s tactic of landing where least expected: the northern coast’s sparsely populated area of docks, coves (then called sacos), hills, and islands, later radically altered in the early 20th century for the modern port.

Figure 8: A Capital do Brasil (The Capital of Brazil), an 1831 map of Rio de Janeiro.

Source: Digital National Library.

Where exactly did Duguay-Trouin land? Lagrange recounts:

At 8 a.m., with all launches and small vessels, duly manned, assembled near the three designated ships to coordinate the assault—that is, with all landing forces—we approached a cove so full of rocks that, unable to reach shore, our soldiers had to wade waist-deep in water to the beach, where officers awaited to organize them into combat order as they arrived. We encountered no resistance there. (Lagrange, 1967, p. 64)

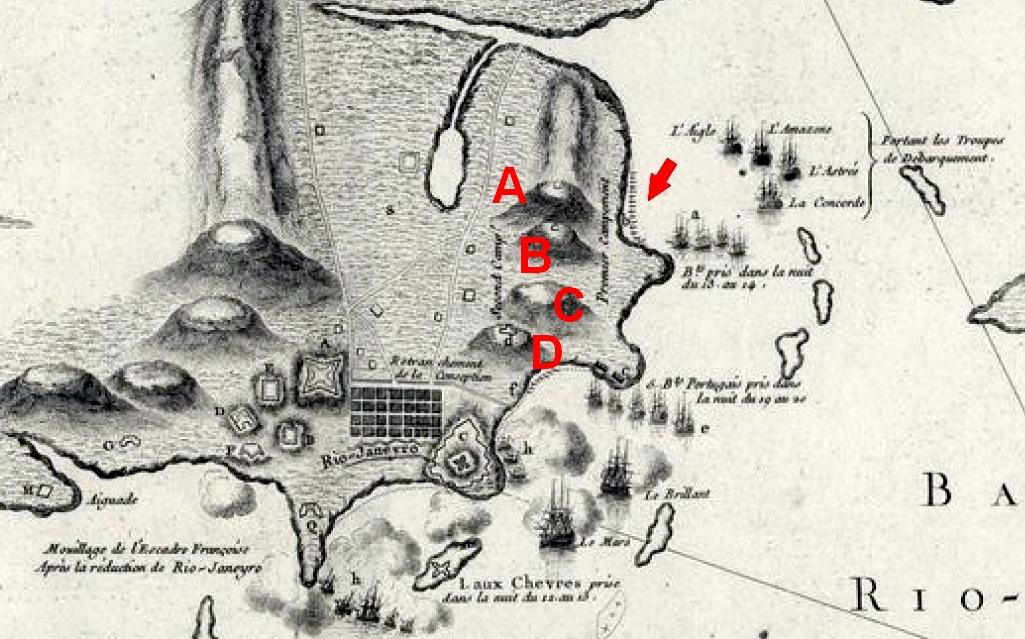

But which cove? The map “Prise de Rio-Janeyro 1711” (“Capture of Rio de Janeiro 1711”) shows the landing occurred at Praia do Saco do Alferes (Ensign’s Cove Beach), whose outline corresponds to present-day Santo Cristo Street in the neighborhood of the same name. The beach and cove (saco) were named after Ensign Diogo de Pina, a local resident.

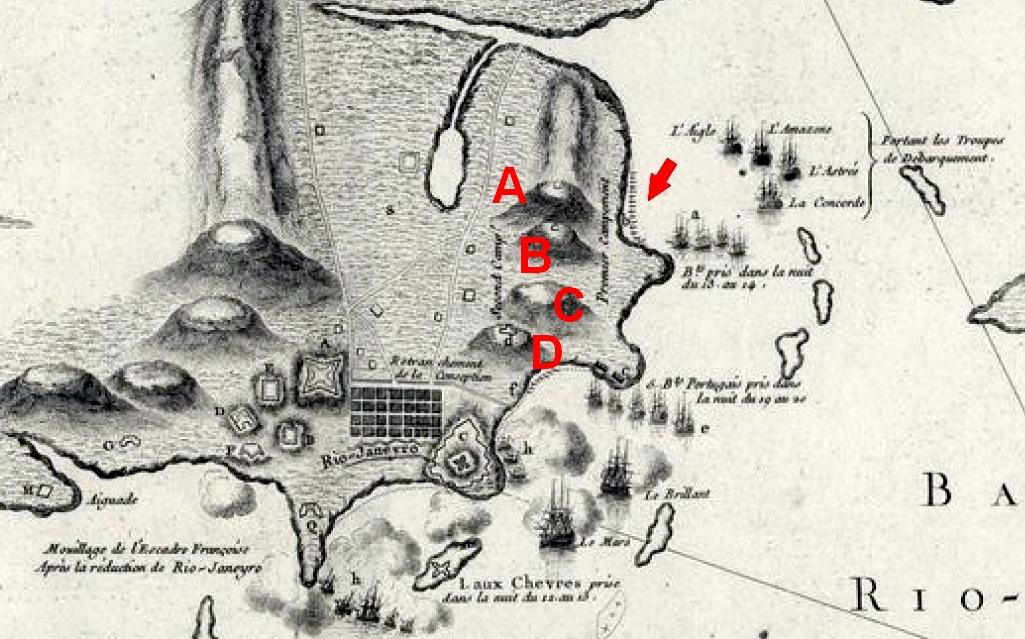

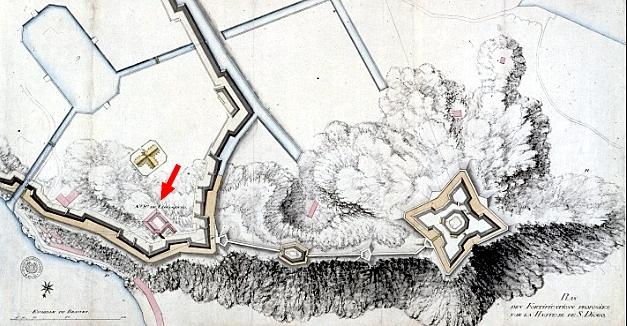

Figure 9: Landing site of Duguay-Trouin’s troops at Saco do Alferes (arrow). On the opposing hills, marked with squares at their peaks, the French established their Premier Campement (First Encampment): today’s Morro do Pinto (A) and Providência Hill (B). Note Livramento Hill (C), erroneously separated from Providência on the map, and Conceição Hill (D), site of the episcopal palace captured a week later for their Second Camp.

Source: Detail from the map ”Prise de Rio-Janeyro 1711”.

After landing, the French occupied the opposing hills to plan their advance. Duguay-Trouin writes in his memoirs:

Once troops and munitions were ashore, I ordered Sir de Goyon and Sir de Courserac to advance with their brigades and seize the two hills, from which the entire plain and the city’s movements could be observed. [...] Our troops camped as follows: Goyon’s brigade occupied the hill facing the city; Courserac’s took the opposite hill; and I positioned myself centrally with the main brigade. (Duguay-Trouin, 1884, p. 70-71)

Which hills were these? Examining the *Prise de Rio-Janeyro 1711* map and Jacques Funck’s 1768 map of Rio’s fortifications (below), we see they were: Morro do Pinto (A), once called Monte de Santa Teresa (due to its chapel) and later Morro do Nheco (the current Santa Teresa Hill was then Morro do Desterro). Providência Hill (B). This is corroborated by the panoramic views both hills offer of the city, bay, and western "backlands."

Figure 10: Detail showing the two hills occupied by French invaders after landing at Saco do Alferes.

Source: Jacques Funck, Relation generale de toutes les Forteresses a Rio de Janeiro, 1768, Digital National Library.

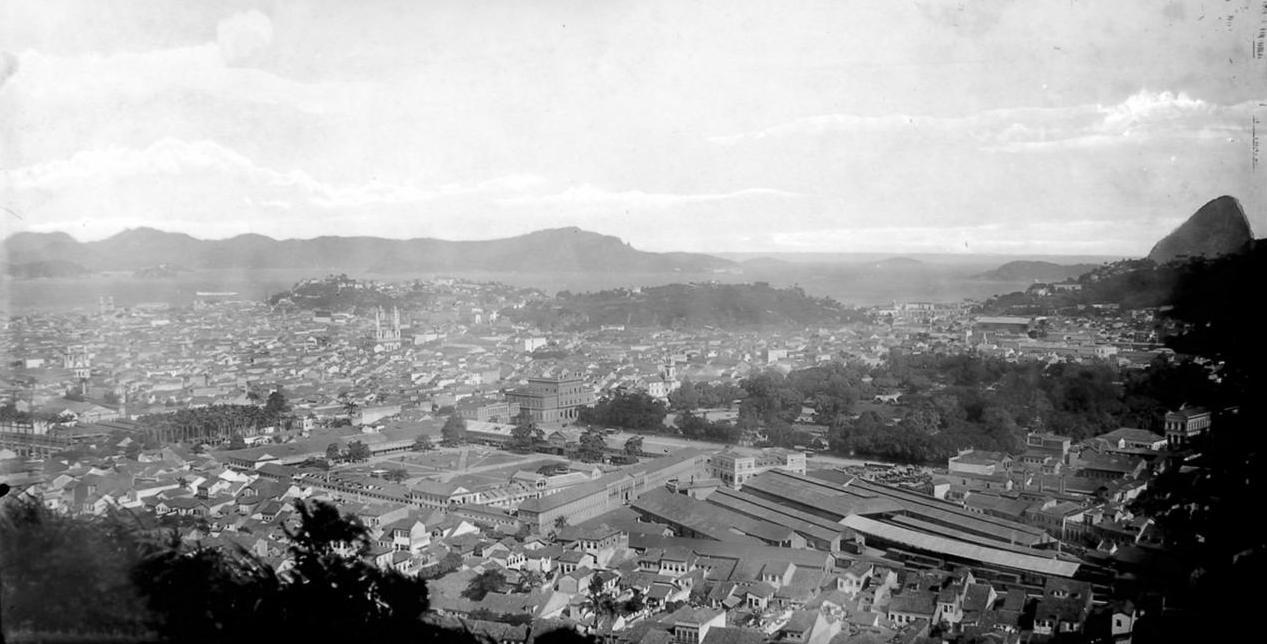

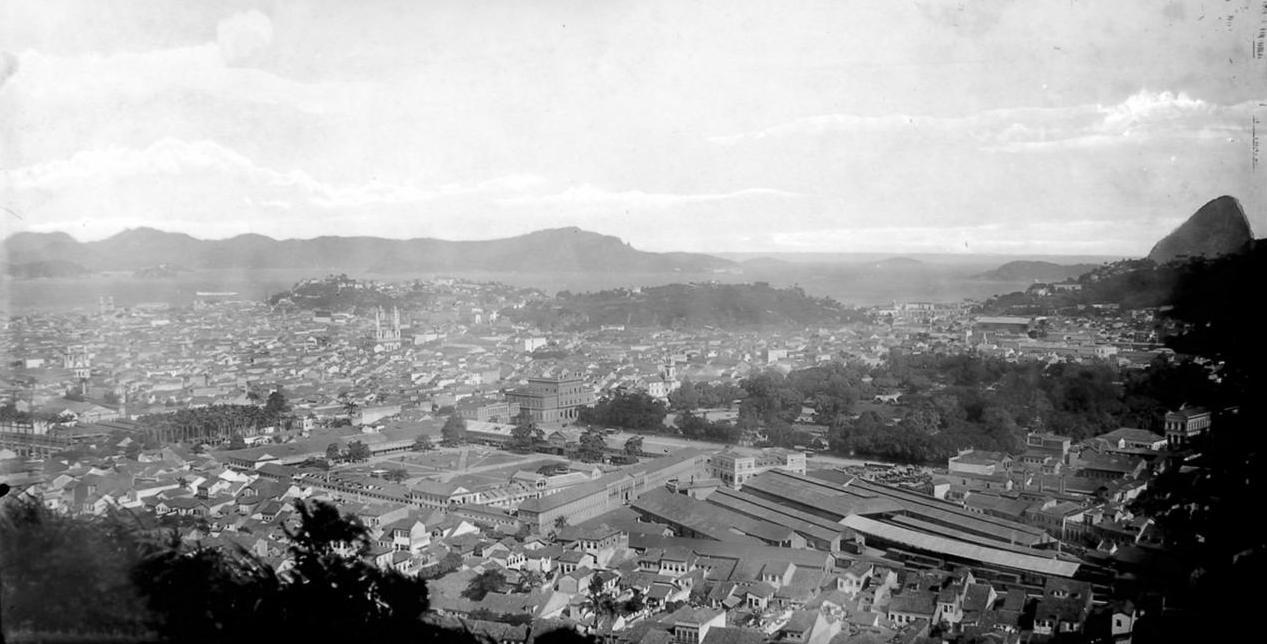

Figure 11: Marc Ferrez, Vista do centro da cidade a partir do Morro da Providência (View of the City Center from Providência Hill), circa 1890.

Source: Brasiliana Fotográfica.

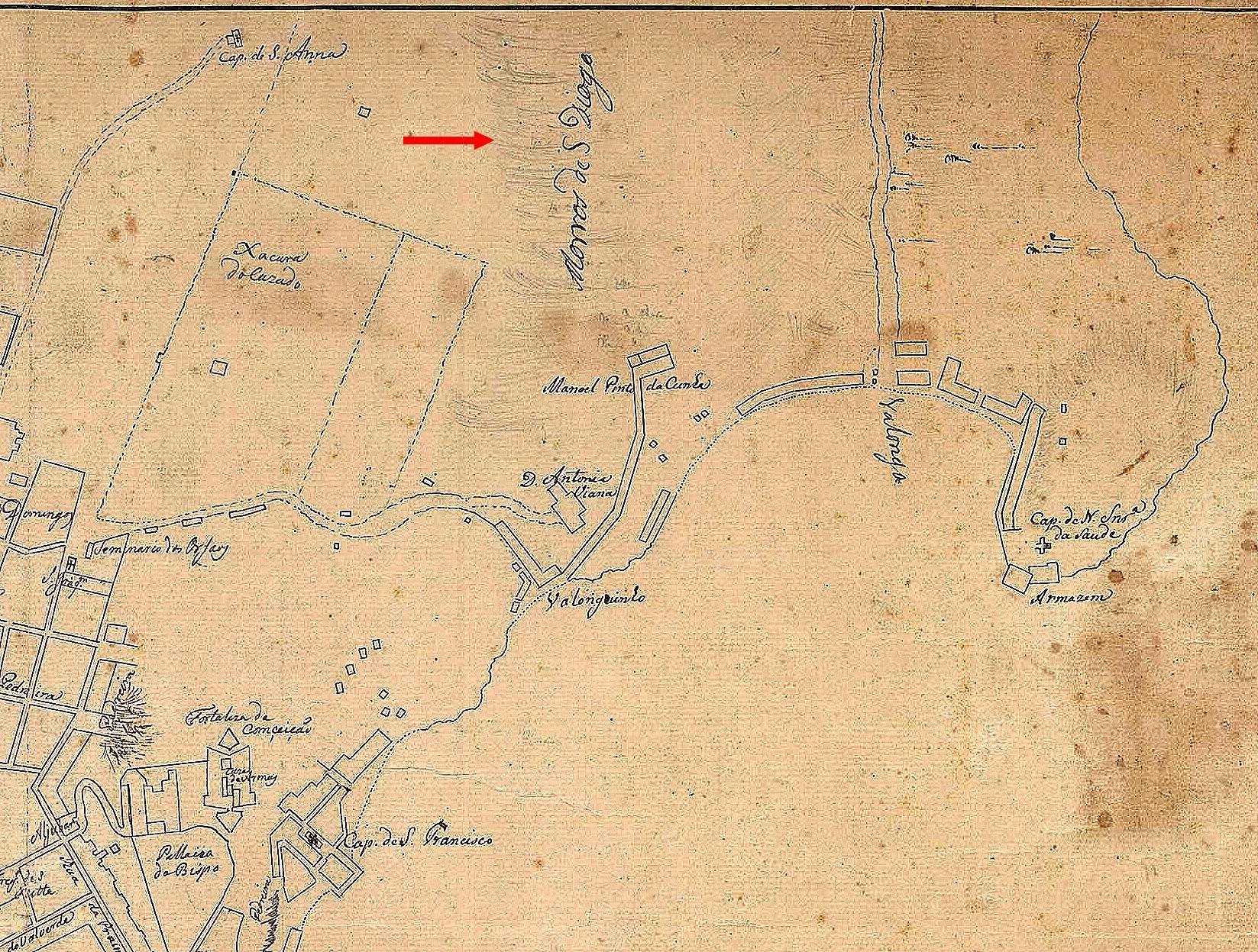

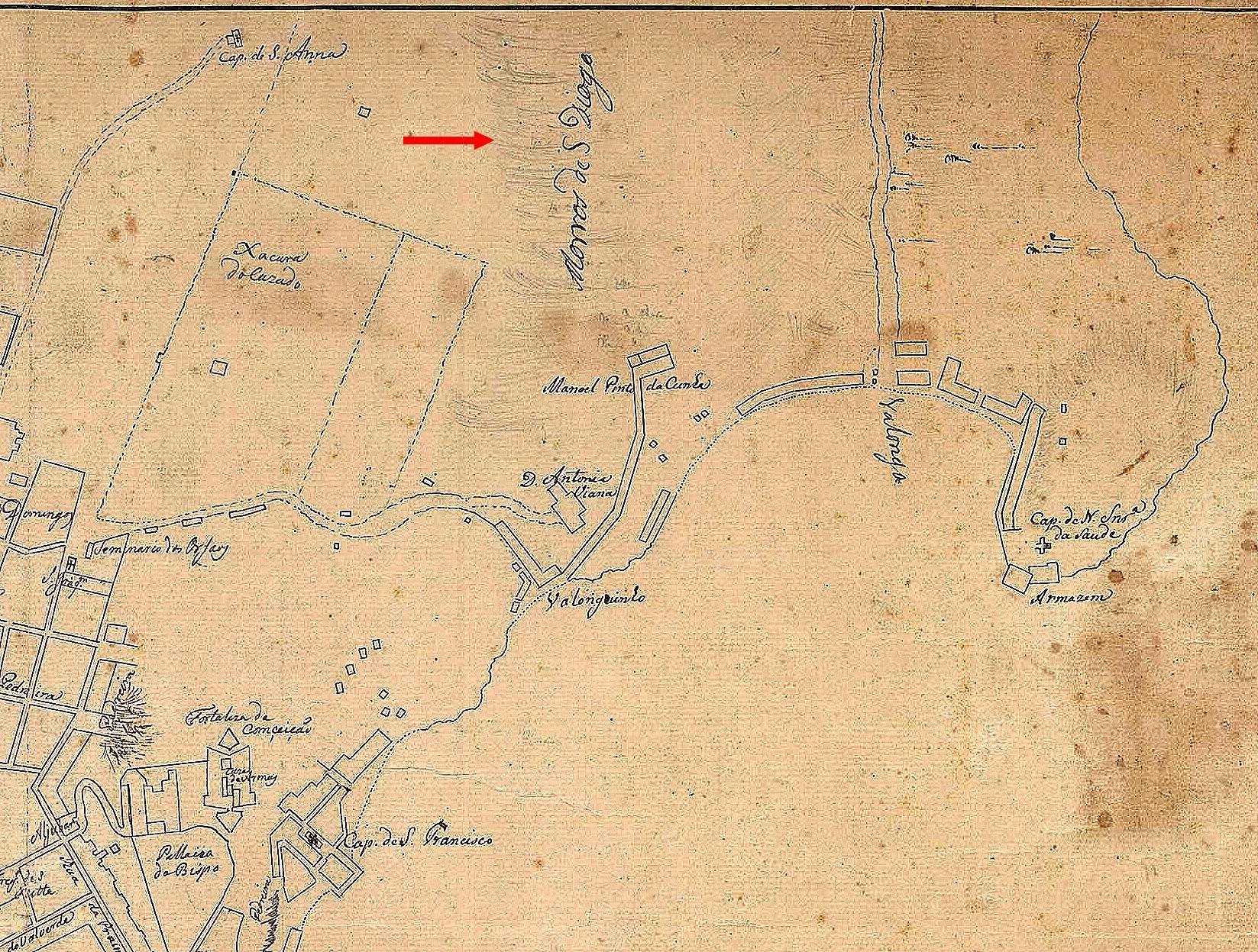

Naming conventions complicate the study, as place names evolved over time, and unofficial terms like Morro da Favela for Providência Hill emerged. The Efemérides Brasileiras by Barão do Rio Branco states Duguay-Trouin “occupied without resistance the heights of São Diogo, Providência, and Livramento.” However, we argue “São Diogo” here refers not to the actual São Diogo Hill (near Leopoldina Station) but to Morro do Pinto. This is supported by an 1850 map (below) where “Morros de S. Diogo” designates both São Diogo Hill and part of Morro do Pinto. The “Prise de Rio-Janeyro 1711” map clearly shows the French occupied the two hills facing Saco do Alferes: Pinto and Providência.

Figure 12: Detail from Plano que compreende a planta da Corte do Rio de Janeiro e os seus Subúrbios (Plan of the Court of Rio de Janeiro and Its Suburbs), 1850.

Source: Digital National Library.

2.2 O Morro da Providência nos séculos XIX e XX

Duguay-Trouin remained in Rio for two months, withdrawing only after extorting a hefty ransom. In 1811, the first open-air cemetery, Cemitério dos Ingleses (English Cemetery), was established at the foot of Providência Hill. Over the 19th century, the hill—especially its lower slopes—was gradually occupied by low-income residents and even criminals. Contemporary newspapers depict it as a lawless, neglected area. For example, Correio Mercantil of April 30, 1848, reports:

While public attention turns to the museum on Providência Street, no one remembers Providência Hill—or rather Morro da Formiga [its southern slope’s name at the time]—where there is no providence of any kind, not even light, as patrols ignore the hill’s existence and pedestrians avoid it. Yet, despite its small size, it is densely populated, offering felons a perfect refuge from police. (Publicações [...], 1848, p. 2)

On July 19, 1857, Correio Mercantil notes on page 2, signed by “A Grateful Resident,” the arrival of public lighting: “Providência Hill lacked lamps, but through the authorities’ efforts, they have now been installed for the comfort and safety of its residents.”

A Diário do Rio de Janeiro note from August 13, 1868, titled “Morro da Providência,” states the hill had “over 100 houses housing more than 1,000 people, drawn by low rents and healthy air,” dispelling the myth that it was uninhabited before the Canudos veterans’ arrival.

By 1896, as the Canudos War raged, a few shacks already stood on the hill’s summit, as reported in O Paiz on January 27:

Another ferocious, bestial act bloodied the already crimson January of 1896. At 6 p.m., under a serene sunset, the hilltop—covered in vegetation and sparsely dotted with zinc-roofed shacks—became the stage for a crime of barbaric stupidity. (Homicidio, 1896, p. 1)

The 1866 issue of Bazar Volante (no. 20B, p. 7) suggests renaming Providência Hill “Mount Hell, Satan’s Knob, Purgatory of Life, or Exile Ridge”.

Call it what you will, but don’t call it Providence Hill!... Do not let the poor people, who still cling to a shred of belief and a sliver of faith, suffer the misfortune of losing them by mistaking the scourges endured on their hill as gifts from Providence! (Nihil, 1866, p. 7)

While Livramento Hill had a chapel by the early 19th century, as noted by Father Perereca in Memórias para Servir à História do Reino do Brasil[3], Providência Hill only gained two religious sites in the early 20th century: the Church of Nossa Senhora da Penha and the “Oratory” in question (Perereca, 2013).

The Oratory’s religious role extended beyond its 1901 inauguration. For example, Correio da Manhã of September 20, 1902, announces on page 4:

GREAT FESTIVITIES [...] in honor of Our Lady of Penha. At 11 a.m., a Mass will be celebrated out of devotion by Canon Curio, vicar of the Parish of the Lord of Santo Cristo. At 5 p.m., the processions will depart, carrying the floats of Our Lady of Penha, Saint Benedict of the Seafarers, and the Lord Good Jesus of the Mount, which, in visitation to the Crucified Lord Good Jesus of the Lookout, circle around His hermitage erected at the top of Providência Hill [that is, the Oratory]. (Grandes [...], 1902, p. 4)

The Jornal do Brasil of September 24, 1911, announces a procession “in honor of the Lord Good Jesus of the Lookout, circling the Twentieth Century monument” (Irmandade [...], 1911, p. 14). From that point on, announcements of religious festivities at that location disappear from Jornal do Brasil, reappearing for the last time on page 10 of the July 19, 1931 edition: “Tomorrow, a great religious festivity will take place at the Chapel of the Lookout, at the top of the Favela” (Capella [...], 1931, p. 10). That was likely the last Mass celebrated there, as by then it was already considered an “inhospitable” place, as revealed at the end of the note, which praises the vicar of the Church of Santo Cristo and two young devotees who, “not shunning sacrifice, overcome, so to speak, the inhospitable quarries of the Favela” (Capella [...], 1931, p. 10).

The term Oratório do Morro da Providência was adopted only in the 1980s during its preservation. In the early 20th century, it was called Monumento do Século XX, Monumento do Bom Jesus do Mirante, or Capela do Senhor Bom Jesus do Mirante, housing a life-sized statue of Christ (Senhor [...], 1926, p. 18)[4].

By the 20th century, the hill was fully occupied by the favela, reaching the Oratory at its peak and the English Cemetery at its base. In his 1924 chronicle A Favela que eu vi (The Favela I Saw), journalist Benjamim Costallat describes his ascent:

– Shall we go to the hill of crime?

– Let’s go…

From afar, Favela’s tiny shacks resembled a vast nativity scene.

We descended onto América Street, one of Rio’s filthiest, mud-choked lanes.

Linked to Morro do Pinto by the Ponte dos Amores (Bridge of Loves), Favela’s shacks glinted in the sun.[5]

Ponte dos Amores! It might as well be Venice’s Bridge of Sighs. Though crudely wooden, not marble, it has witnessed agonized sighs...

Not long ago, daylight robberies occurred here; nighttime murders.

Today, it’s safer—but still perilous, sheltering the violent loves of hustlers and creole women... (Costallat, 1990, p. 33)

In 1952, the film Tudo Azul featured a scene at the Oratory, with washerwomen carrying water cans to the tune of “Lata d’água na cabeça / Lá vai Maria” sung by Marlene. By 2010, Providência Hill housed 4,094 residents (Nunes, 2025).[6]

Figure 13: Scene from Tudo Azul (1952), directed by Moacyr Fenelon, filmed in front of the Oratory.

Source: Screenshot from Tudo Azul, available on YouTube.

Fortification of the City After the 1711 Scare

The humiliation of the 1711 invasion spurred governors and later viceroys to "make up for losses" by prioritizing the city’s fortification. Given the privileged vantage point from Providência Hill’s summit, one might expect it to have been utilized at least as an observation watchtower.

The first fortification plan, commissioned shortly after the invasion from French engineer Jean Massé, proposed expanding and renovating coastal forts, constructing or upgrading fortifications atop four hills (Conceição, Santo Antônio, São Bento, and Castelo), and building a wall between Castelo and Conceição Hills to defend the urban core, a project ultimately abandoned as it hindered the city’s natural expansion (Santos, 2009). The Fortress of Conceição, included in the plan, was completed in 1718. The hills near Duguay-Trouin’s landing site, outside the planned wall, were not addressed in Massé’s plan.

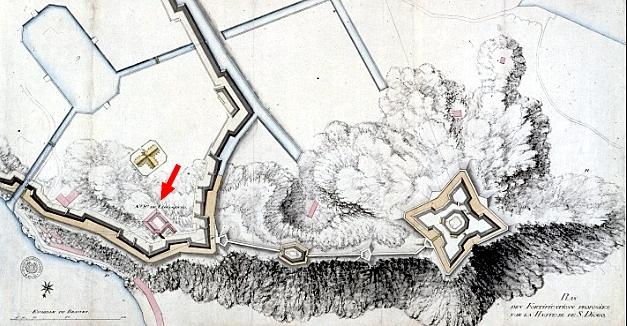

Swedish engineer Marshal Jacques Funck’s 1768 plan, however, did consider these hills, offering the following recommendations:

The only current defense on the inland side consists of two fortresses, São Sebastião [on Castelo Hill] and Conceição, which are of little use for that area. Moreover, they neither protect nor dominate their suburbs, essential for proper defense, due to the dense housing that now extends far beyond these forts into the inland region, obstructing their effectiveness. Beyond these issues, the fortresses suffer the critical flaw of being overshadowed by two much higher elevations inland: one called Monte de São Diogo, west of the city, and the other Monte de Santa Teresa, south of the city. Their peaks, nearly equal in height above sea level and equidistant from the city, slope sharply toward the bay. These two heights encircle the city and its suburbs, fully dominating them. São Diogo commands the entire western inland area and part of the bay’s shore, while Santa Teresa overlooks the southern inland front and a stretch of the southern shore. The remaining southern inland area is shielded by a lofty ridge called Monte da Pedreira [now Morro da Nova Cintra], which connects to Santa Teresa and lies behind the city. (Antunes, 1957, p. 17)

Funck notes that the city (today’s downtown) was "commanded" (in the military sense of "overlooking from a superior elevation" — per definition 10 of "command" in Houaiss Dictionary) to the west by Monte de São Diogo and to the south by Monte de Santa Teresa. By this time, Monte de Santa Teresa no longer referred to the current Morro do Pinto but to the hill still known by that name, famous for its tram. Funck states both hills were similarly elevated and far higher than Castelo and Conceição. The only hill on the northern coast of the city (today's Port Zone) with a height similar to that of Morro de Santa Teresa is Morro da Providência, at 115 meters – while Curvelo, in Santa Teresa, stands at 117 meters.

The “Plan des Fortifications Proposées sur la Hauteur de S. Diogo” ("Plan for Proposed Fortifications on São Diogo Hill"), drawn by Funck himself, labels the site “NA SA DE LIVRAMENTO” under an arrow (visible only when zoomed in), confirming it refers to Providência Hill.

Figure 14: Plan des Fortifications Proposées sur la Hauteur de S. Diogo (Plan for Proposed Fortifications on São Diogo Hill) by Jacques Funck.

Source: Rede Memória.

A 1760 manuscript map of colonial Rio also indicates that Morro de São Diogo at the time designated Livramento/Providência Hills.

Figure 15: Detail from a 1760 Colonial Rio Map.

Source: Digital National Library.

Viceroy Conde de Resende was deeply committed to the city’s defense. In his article Fortificações do Rio de Janeiro, General Paranhos Antunes references:

A valuable collection of plans commissioned by Conde de Resende, Viceroy of Brazil, showing newly erected batteries for defending Rio de Janeiro, alongside repairs and expansions to key fortresses, preceded by two bay plans illustrating the “harbor entrance and anchorages,” accompanied by artillery inventories. (Antunes, 1957, p. 17)

In order to avoid the proliferation of batteries along the Saco da Gamboa and Alferes areas and the expenses they would entail, it was decided that two armed vessels, positioned at the time between Morro da Saúde and Ilha das Pombas (now Ilha de Santa Bárbara), would defend the entrance to the aforementioned inlets. ‘However, these must always be protected by the fortification intended to be built on the summit of Monte de Paulo da Caieira – a place of great advantage, as it commands the aforementioned inlets to its north, and also commands, from west to south, Mata Porcos (Caminho do Mata Porcos, now Rua Estácio de Sá), the road that leads to the city, and part of the Campo de Santana; and from south to east to north it commands the rest of Campo de Santana, a large portion of the city, and the Fortaleza da Conceição.’ (Antunes, 1957, p. 17)

Thus, plans emerged to build a fortification on Monte de Paulo da Caieira, none other than Providência Hill.

Figure 16: Detail from the “Map of the City of S. Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro, surveyed by Order of His Royal Highness” from 1812, in which Morro da Providência is referred to as Monte de Paulo da Caeira.

Source: Digital National Library.

Attempting to Decipher the Mystery of the Oratory

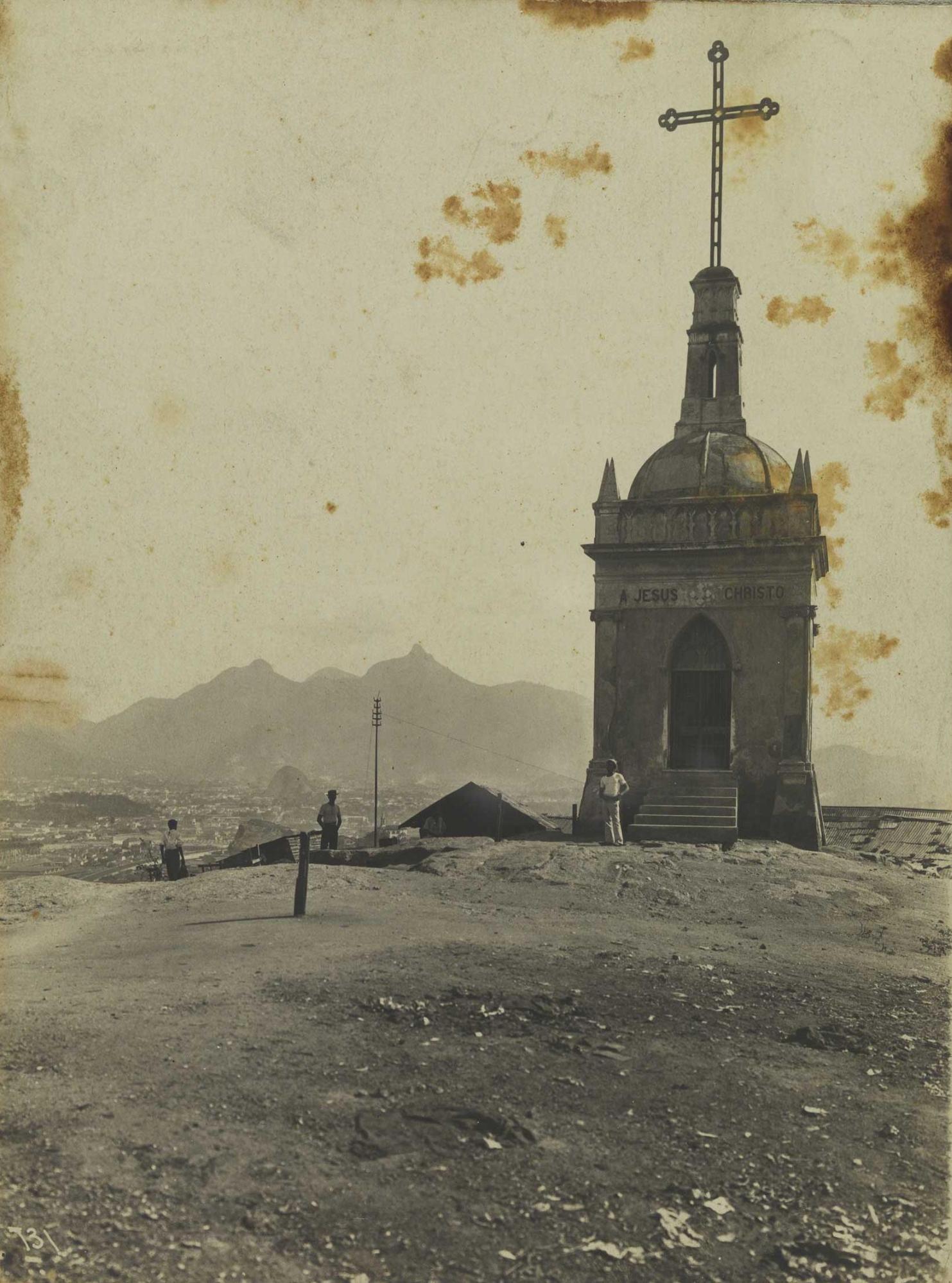

Figure 17: The Oratory photographed by Augusto Malta in the early 20th century.

Source: Digital National Library.

The claim that the oratory was built by soldiers returning from Canudos collapses under closer scrutiny. When photographed by Augusto Malta in the early 20th century, the "Oratory" displayed a large cross at its peak and an inscription above its ogival door reading "A JESUS CHRISTO" (both the inscription and cross have since been lost). Contemporary newspapers and magazines reveal it was inaugurated on January 1, 1901, the first day of the 20th century, explicitly to commemorate the turn of the century.

A closer reading of inauguration reports uncovers intriguing details. For example, on page 2 of the December 15, 1900, issue of the Catholic weekly ‘O Apóstolo’, we read:

The monument, a grand cross to be erected on Providência Hill to commemorate the turn of the century and this people’s love for Jesus Christ the Redeemer, is nearly complete. It will be blessed and inaugurated on the 31st of this month by His Excellency the Most Reverend Archbishop. Our praise to its promoters. (MONUMENTO, 1900a, p. 2)

The December 22, 1900, issue of the same paper announced on page 2: “The inauguration of the Cross, a monument honoring Jesus Christ on Providência Hill, will take place on January 1 at 5 p.m., to be blessed by His Excellency Archbishop D. Joaquim Arcoverde.” (MONUMENTO, 1900b, p. 2)

Gazeta de Notícias of December 24, 1900, reported on its front page under ‘Cruz Commemorativa’:

The beautiful monument commemorating the turn of the century atop Providência Hill is complete. The tireless efforts of the committee led by Canon Curio have succeeded. On the 1st, Mass will be celebrated there—a true open-air Mass, with the sky as its canopy and one of the capital’s most splendid vistas as its backdrop. On the night of December 31 to January 1, as the 19th century ends and the 20th dawns, the monument will be illuminated. Each of its three doors will bear a luminous cross visible and revered from great distances. The Mass, celebrated by Canon Curio, will occur at 10 a.m. on January 1. One can easily imagine the spectacle at such a lofty city point, capable of accommodating countless faithful. At midnight, an enormous balloon with a luminous cross on one side will ascend [...] On the afternoon of the 1st, the Archbishop will visit the monument. His Excellency will ascend via Barroso Slope, and residents along the route are preparing festive decorations to welcome the prelate entrusted with this archdiocese. The event promises to captivate Catholic families. (CRUZ..., 1900, p. 1)

Jornal do Brasil of December 28, 1900, noted on its front page under A Passagem do Século:

The entire Christian world prepares to solemnize the passage from the expiring century to the 20th [...]. In Rio de Janeiro, as in all Catholic lands, the Church will mark the occasion with Masses across parishes. At Providência Hill, the grand cross honoring Jesus Christ the Redeemer will be inaugurated, followed by a solemn Mass at 10 a.m. Beyond religious ceremonies, the organizing committee will use remaining funds for public festivities on the 31st. Fireworks will blaze over Providência, Valongo, Viúva, Castelo, and other hills, while twenty military bands parade through the city and suburbs at midnight. (PASSAGEM..., 1900)

O Paiz of December 30, 1900, reported on page 2 under ‘O Século XX’: “At 10 a.m. on January 1, the commemorative cross marking the turn of the century will be solemnly inaugurated on Providência Hill, attended by the Metropolitan Archbishop.” (SÉCULO..., 1900)

Note that the newspaper articles suggest that the “monument” being inaugurated is the “grand cross,” the “commemorative cross,” or the “great cross” (which was later lost) at the summit, not the entire structure. Was the cross, then, erected atop a preexisting construction at the top of the hill? And if so, what construction might that have been?

The 1881 photograph and the engravings from 1847 and around 1860 at the beginning of this article confirm that this was indeed the case. Furthermore, several old maps show the existence of a structure at that location. For example, the “Plan of the City of São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro, drawn up by order of His Royal Highness the Prince Regent Our Lord in the year 1808,” already discussed in this article, and this “Plan of the City of Rio de Janeiro” from 1791.

Figure 18: Plano da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro com a Parte Mais Essencial do seu Porto e Todos os Lugares Fortificados (Plan of Rio de Janeiro with Key Port Areas and Fortified Sites), surveyed by Marshal Jacques Funck in 1788 and expanded per the 1791 city plan.

Source: Digital National Library.

4.1 But What Was This Structure?

To answer this second question, I will draw upon a thesis proposed by independent researcher Gilmar José Santana de Barros[7], which he kindly shared with me during our discussions on the subject and allowed me to include in this article. His idea is that the “great cross” inaugurated around the turn of the 20th century was erected atop an old abandoned watchtower, either a remnant of the French occupation of the hills or built in the 18th century during the wave of city fortifications, which also led to the construction of the Fortaleza da Conceição. According to him, “the very thick walls suggest an old construction,” and the doors offering broad views of the four cardinal points support the thesis that it was a “maritime watch post.” The ogival shape of the doors may have resulted from the conversion of the old, abandoned watchtower into an oratory during the neogothic vogue, as exemplified by the Fiscal Island castle inaugurated in 1889. Originally, the watchtower served to monitor the coast, especially considering its strategic location covering the inner bay, Praia Formosa, Saco do Alferes, and Praia de São Cristóvão, areas vulnerable to intrusion as they could not be observed from the three main promontories in the city center: São Bento, Conceição (which was set back), and Morro do Castelo.

This theory aligns with Marshal Funck’s fortification plans and those commissioned by Conde de Resende (discussed earlier), which, though not fully implemented, may have spurred at least an observation post on Providência Hill. This theory is further supported by military engineer Augusto Fausto de Sousa’s statement in the article “Fortificações no Brasil” (“Fortifications in Brazil”), found on page 111 of volume 48, Part II, of the Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, in which he affirms that “a multitude of batteries and small forts existed all along the shoreline from Gamboa to Praia do Arpoador.”

To conclude, I present two recent photographs for the reader’s appreciation:

Figure 19: Front view of the Oratory, photographed in 2015.

Source: Personal Archive.

Figure 20: Rear view of the Oratory, photographed in 2015.

Source: Personal Archive.

References

ANTUNES, G. D. PERANHOS. Fortificações do Rio de Janeiro: Memórias e Relatórios - Conclusão. Jornal do Commercio, Rio de Janeiro, ano 130, n. 184. 12 May 1957. 3º Caderno, p. 17. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/364568_14/43656. Accessed on: 13 May 2025.

CAPELLA do Bom Jesus do Mirante (Favela) da Parochia de Santo Cristo dos Milagres. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, ano 41, n. 172. 19 Jul. 1931. Secção Religiosa, p. 10. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/030015_05/14937. Accessed on: 12 May 2025.

COSTALLAT, Benjamim. Mistérios do Rio. Rio de Janeiro, Biblioteca Carioca, 1990.

CRUZ commemorativa. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, ano 26, n. 357. 24 Dec. 1900. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/103730_04/1684. Accessed on: 13 May 2025.

CUNHA, Euclides da. Os Sertões. Ministério da Cultura, Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, Departamento Nacional do Livro, s.d.. Available at: http://www.dominiopublico.gov.br/pesquisa/DetalheObraForm.do?select_action=&co_obra=2163.

EDMUNDO, Luís. O Rio de Janeiro do meu tempo. Brasília, Edições do Senado Federal, 2003.

GRANDES festas. Correio da Manhã. Rio de Janeiro, ano 2, n. 463. 20 Sep. 1902. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/089842_01/2516. Accessed on: 12 May 2025.

HOMICIDIO. O Paiz, Rio de Janeiro. Ano 12, n. 4134, 27 Jan. 1896. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/178691_02/14780. Accessed on: 12 May 2025.

IRMANDADE de Nossa Senhora da Penha. Conclusão de suas festividades. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, ano 21, n. 267. 24 Sep. 1911. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/030015_03/10255. Accessed on: 12 May 2025.

LAGRANGE, Louis Chancel de. A tomada do Rio de Janeiro em 1711 por Duguay-Trouin. Traduzido por Mário Ferreira França. Rio de Janeiro, Departamento de Imprensa Nacional, 1967. Available at: https://imprensa2.in.gov.br/o/biblioteca-digital-internet-lf7_1-ce-theme/pdf/index.html?file=https://imprensa2.in.gov.br/documents/20127/0/A+Tomada+do+Rio+de+Janeiro+em+1711+por+Duguay+-+Trouin.pdf/8fb1e007-4489-04ae-3cbb-d3facbcfbeb5. Accessed on: 12 May 2025.

UM MONUMENTO. O Apóstolo, Rio de Janeiro, ano 36, n. 73. 15 Dec. 1900. Noticiario, p. 2. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/343951/16586. Accessed on: 13 May 2025.

MONUMENTO. O Apóstolo, Rio de Janeiro, ano 36, n. 74. 22 Dec. 1900. Noticiario, p. 2. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/343951/16590. Accessed on: 13 May 2025.

MORADOR AGRADECIDO, O. Correio Mercantil, Rio de Janeiro, Ano 14, n. 196, 19 Jul. 1857. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/217280/13555. Accessed on: 12 May 2025.

MORRO da Providência. Diário do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Ano 51, n. 222, 13 Aug. 1868. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/094170_02/23292. Accessed on: 12 May 2025.

NIHIL. [Untitled]. Bazar Volante. Rio de Janeiro, ano 3, n. 20. Feb. 1866. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/docreader/714194/561. Accessed on: 12 May 2025.

NOTÍCIAS diversas. Correio Mercantil, Rio de Janeiro, Ano 13, n. 171, 21 Jun. 1856. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/217280/12008. Accessed on: 12 May 2025.

NUNES, Gabriel. Morro da Providência. 2025. Dicionário de Favelas Marielle Franco. Available at: https://wikifavelas.com.br/index.php/Morro_da_Provid%C3%AAncia. Accessed on: 12 May 2025.

A PASSAGEM do século. Jornal do Brasil, ano 10, n. 362. 28 Dec. 1900. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/030015_02/9199. Accessed on: 13 May 2025.

PERERECA, Padre (Luís Gonçalves dos Santos). Memórias para Servir à História do Reino do Brasil. Brasília, Edições do Senado Federal, 2013.

PUBLICAÇÕES a pedido. Correio Mercantil, Rio de Janeiro, Ano 5, n. 118, 30 April 1848. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/217280/473. Accessed on: 12 May 2025.

RIO DE JANEIRO. Prefeitura Municipal. Guia do Patrimônio Cultural Carioca: Bens Tombados. Rio de Janeiro, 2014, 5a ed.

SANTOS, Jorge Paulo Pereira dos. O papel das invasões francesas nas estratégias de reestruturação da defesa do Rio de Janeiro no século XVIII. 2009. 129 f. Dissertation (Master’s in Geography) - Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2009.

O SÉCULO xx. O Paiz, ano 17, n. 5928. 30 Dec. 1900. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/178691_03/1830. Accessed on: 13 May 2025.

SENHOR Bom Jesus do Mirante. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, ano 36, n. 167. 15 Jul. 1926. Avisos Funebres, p. 18. Available at: http://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/030015_04/48026. Accessed on: 12 May 2025.

About the Author

Ivo Korytowski, graduated and licensed in Philosophy from UFRJ (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro), is an award-winning writer, retired translator, researcher of Rio de Janeiro’s history, blogger, and YouTuber. His articles have been published in numerous journals, including Revista Brasileira da ABL, Revista do IHGB, Revista do IHGRJ, and others.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K.; methodology, I.K.; software, I.K.; validation, I.K.; formal analysis, I.K.; investigation, I.K.; resources, I.K.; data curation, I.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K.; writing—review and editing, I.K.; visualization, I.K.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

About Coleção Estudos Cariocas

Coleção Estudos Cariocas (ISSN 1984-7203) is a publication dedicated to studies and research on the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, affiliated with the Pereira Passos Institute (IPP) of the Rio de Janeiro City Hall.

Its objective is to disseminate technical and scientific production on topics related to the city of Rio de Janeiro, as well as its metropolitan connections and its role in regional, national, and international contexts. The collection is open to all researchers (whether municipal employees or not) and covers a wide range of fields — provided they partially or fully address the spatial scope of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Articles must also align with the Institute’s objectives, which are:

- to promote and coordinate public intervention in the city’s urban space;

- to provide and integrate the activities of the city’s geographic, cartographic, monographic, and statistical information systems;

- to support the establishment of basic guidelines for the city’s socioeconomic development.

Special emphasis will be given to the articulation of the articles with the city's economic development proposal. Thus, it is expected that the multidisciplinary articles submitted to the journal will address the urban development needs of Rio de Janeiro.

[1] Jean-François Duclerc was a French privateer who attacked Rio de Janeiro in late August 1710 but was defeated.

[2] The author of the narrative, 1st Lieutenant Louis Chancel de Lagrange, served aboard the frigate L’Aigle, one of the seventeen ships that comprised the French fleet of René Duguay-Trouin.

[3] The priest writes: “the great Morro do Livramento continues on the same side, and on its summit one notices a beautiful country house, and next to it the little chapel of Our Lady, of the same invocation.”

[4] As revealed by an announcement from the chapel’s caretaker, Thereza Maria de Jesus, on page 18 of the Jornal do Brasil, dated July 15, 1926, entitled “Senhor Bom Jesus do Mirante,” in which she requests contributions “whether in money or in materials” for the restoration of its interior.

[5] With the construction of the overpass in the 1970s, the bridge connecting the two hills was demolished.

[6] Marielle Franco’s Dictionary of Favelas, entry “Morro da Providência.”

[7] The aforementioned researcher never published an article presenting his thesis. After reading a post about the Oratory, which I had visited, on my blog “Literatura, Rio de Janeiro & São Paulo”, he contacted me and shared his watchtower hypothesis. Initially skeptical, I dismissed it, but he sent further arguments and evidence that ultimately convinced me. I suggested he write an article, but he declined, so I proposed deepening the study and writing about the topic myself, to which he agreed. After the pandemic, unfortunately, I lost contact with him and have been unable to reach him since.