Volume 13 Issue 3 *Corresponding author fj.moraes3@gmail.com Submitted 26 apr 2025 Accepted 1 jul 2025 Published 13 jul 2025 Citation MORAES JUNIOR, Flávio José. Invisible Heritage: slavery, illegal trafficking, and the urgent need to preserve the Casa do Porto in the Western Zone of Rio de Janeiro. Coleção Estudos Cariocas, v. 13, n. 3, 2025. DOI: 10.71256/19847203.13.3.140.2025 The article was originally submitted in PORTUGUESE. Translations into other languages were reviewed and validated by the authors and the editorial team. Nevertheless, for the most accurate representation of the subject matter, readers are encouraged to consult the article in its original language.

| Invisible Heritage: slavery, illegal trafficking, and the urgent need to preserve the Casa do Porto in the Western Zone of Rio de Janeiro Patrimônio invisibilizado: escravidão, tráfico ilegal e a urgência de tombamento da Casa do Porto na Zona Oeste do Rio de Janeiro Patrimonio Invisibilizado: esclavitud, tráfico ilegal y la urgencia de la protección de la Casa do Porto en la Zona Oeste de Río de Janeiro Flávio José de Moraes Junior¹ 1Universidade Federal Fluminense: Professor Marcos Waldemar de Freitas Reis street, s/nº, São Domingos, Niterói, RJ, CEP 24210-201, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9145-7924, e-mail: fj.moraes3@gmail.com

AbstractThis article analyzes the historical significance of the Casa do Porto, a structure located in Barra de Guaratiba, in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro, as a tangible heritage site linked to both the first and second periods of slavery in Brazil. Through documentary research, oral history, analysis of iconographic sources, and data from the SlaveVoyages.org database, the article demonstrates the site's strategic role in the clandestine landing of enslaved Africans during the 18th and 19th centuries. In light of the vulnerability of the ruins, the study advocates for urgent heritage listing, archaeological research, and memory policies that actively engage the local community. Keywords: Illegal slavery; Tangible heritage; Transatlantic trafficking; Rio de Janeiro; Historical memory. ResumoEste artigo analisa a relevância histórica da Casa do Porto, estrutura localizada em Barra de Guaratiba, Zona Oeste do Rio de Janeiro, como patrimônio material vinculado à primeira e segunda escravidão no Brasil. Por meio de pesquisa documental, história oral, análise de fontes iconográficas e informações do banco de dados SlaveVoyages.org, demonstra-se o papel estratégico do local no desembarque clandestino de africanos escravizados durante os séculos XVIII e XIX. Diante da vulnerabilidade das ruínas, defendemos a urgência de tombamento, estudos arqueológicos e políticas de memória que integrem a comunidade local. Palavras-chave: Escravidão ilegal; Patrimônio material; Tráfico transatlântico; Rio de Janeiro; Memória histórica. ResumenEste artículo analiza la relevancia histórica de la Casa do Porto, una estructura ubicada en Barra de Guaratiba, Zona Oeste de Río de Janeiro, como patrimonio material vinculado a la primera y segunda esclavitud en Brasil. A través de investigación documental, historia oral, análisis de fuentes iconográficas e información del banco de datos SlaveVoyages.org, se demuestra el papel estratégico del sitio en el desembarco clandestino de africanos esclavizados durante los siglos XVIII y XIX. Frente a la vulnerabilidad de las ruinas, se defiende la urgencia de su protección oficial, la realización de estudios arqueológicos y la implementación de políticas de memoria que integren a la comunidad local. Palabras clave: Esclavitud ilegal; Patrimonio material; Tráfico transatlántico; Río de Janeiro; Memoria histórica. |

Introduction

I write this article intending to highlight the urgency of listing, preserving, and studying structures inherited from the first and second slavery periods in Barra de Guaratiba, West Zone of Rio de Janeiro, which are currently in a state of great material vulnerability.

My aim here is to briefly describe, in the first person, the research history concerning the material heritage legacies of slavery in Barra de Guaratiba, in order to demonstrate how my relationship with the territory, as a historian-resident, aided in the perception of these sites and the discovery of oral sources. In 2023, I was awarded a grant for the development of a series about the Santa Cruz neighborhood, located in the West Zone. While researching the neighborhood, which had an extensive territoriality in the 16th century, I came across documents about the Restinga da Marambaia and the location's long history of slavery. The encounter with the archives was a significant find, especially because I live in Barra de Guaratiba and observed that this history had been erased by the urban space, forgotten from the common memory of new generations.

The encounter with the archives and the stories from the slavery period placed me in a mental perspective where I began to imagine the functioning of this institution in the neighborhood. Traditionally in the neighborhood, when the tide is ebbing, residents go down with the tide, letting the current carry them, starting from the mangrove, passing through the Bacalhau Channel, and arriving at the so-called Prainha (Little Beach). It was during one of these tide descents that I noticed a particular element. The channel has two bridges, one built at the beginning of the 20th century and another in the 1970s. Underneath the bridge built in the 1970s, there is a construction, with a base of multiform yellowish stones. I spent hours observing the structure; it seemed evident that the only entrance to Sepetiba Bay for many kilometers had been occupied in the past, being a strategic place, important commercially and militarily.

This article investigates the historical importance of Casa do Porto (Port House), located in Barra de Guaratiba, West Zone of Rio de Janeiro, proposing its preservation as material heritage linked to the Brazilian slave system, with emphasis on the so-called Second Slavery. The research starts from the hypothesis that Casa do Porto was used as a strategic point for the clandestine disembarkation of enslaved Africans, especially after the official prohibition of the slave trade in 1831.

The adopted methodology combines different approaches: document analysis, use of oral history, iconographic survey, and consultation of the international database SlaveVoyages.org. The article draws on authors such as Dale Tomich (2011), Ynaê Lopes dos Santos (2022), Thiago Campos Pessoa (2015, 2018), Marcus de Carvalho (2012), and Maria Sarita Cristina Mota (2009), who provide theoretical and empirical contributions on the functioning of the illegal traffic, the formation of the coffee complex, slaveholding modernity, and land dynamics in nineteenth-century Rio de Janeiro.

By adopting a territorialized perspective, the research incorporates the condition of being a researcher-resident of the region, which contributes to the valorization of oral sources and collective memory as analytical instruments. The article argues that the recognition of Casa do Porto as historical heritage and its consequent preservation can contribute to the construction of memory policies and local cultural and economic development.

Barra de Guaratiba: A Large Sugar Mill

Barra de Guaratiba is a region seldom addressed by historiography. A notable exception is the thesis by Maria Sarita Cristina Mota (2009), which addresses various demographic, economic, and social aspects of the Freguesia de Guaratiba during colonization and the establishment of the first sugar mills. Even research into the illegal slave trade in Marambaia, an area with a robust, complex academic output, rarely mentions the neighborhood. Studies by Ynaê Lopes dos Santos, Hebe Mattos, and Thiago Campos Pessoa have made rich contributions on the so-called second slavery in Marambaia and the Coffee Valley. Their work offered me extensive sources and a clear picture of what this part of the province of Rio de Janeiro represented as a territory.

Figure 1: Personal documentation of ruins at Bacalhau Channel, remnants of the former Port House.

Source: Personal collection.

My first source was oral history. While researching Barra de Guaratiba for a documentary, I met "Mr. Chiquinho," a 96-year-old man with remarkable lucidity and memory. He wrote several books about the neighborhood, documenting key aspects of its history. A descendant of the area’s first fishing colonies, Mr. Chiquinho participated in building the old bridge during WWII. He generously shared extraordinary stories, captured with a poet’s sensitivity, until his passing at age 100. When discussing the ruins, he identified them as the "Port House" – a mansion used for disembarking enslaved people and goods like "secos e molhados" (dry and wet provisions), hence the name Bacalhau Channel (Codfish Channel), derived from dried fish sales for transatlantic voyages. His mother forbade him from playing there due to its dark slavery past; locals believed it was haunted.

Mr. Chiquinho referenced Port House twice in his books. In Barra de Guaratiba, sua vida, seu povo, seu passado (Barra de Guaratiba: their life, their people and their past) (2004), in the subchapter “Temples,” he wrote:

The Church of Nossa Senhora da Saúde, located atop Vendinha Hill, originated from a shelter-like construction and served as a House of Prayer (oratory). Those attending liturgical acts were monitored by guards who were part of a committee.

From that shelter, they supervised the slave trade thanks to the wide view they had of Sepetiba Bay, rivers, and canals, enabling full control over boats entering and leaving for the open sea.

It is concluded that next to the Casa do Porto, which no longer exists but was once built by the tide, near the entrance to the Barra, was the mooring area for the boats. (Siqueira, 2004, p. 21)

In another book, Barra de Guaratiba e a II Guerra Mundial (Barra de Guaratiba and World War II, 2009), he again refers to the so-called “Casa do Porto” while describing the construction of the first bridge over Bacalhau Canal:

To occupy a house called “Casa do Porto,” next to the canal, for the installation of the service managers and office staff. This two-story house was built on the canal rocks, at high tide, by a sugar mill owner who used it to quarantine his enslaved people and even had a custody room there (...) (Siqueira, 2008, p. 29)

In a photo kindly provided by Beto, Chiquinho’s son, we can see a tall mansion with a basement in the place where the new bridge stands today. At the top of the hill, the last white dot is the Church of Nossa Senhora da Saúde, a prime observation point overlooking Casa do Porto. Interestingly, amid the current ruins, there is a stone gallery through which rainwater from Caminho da Vendinha flows. Likely, more than 200–300 years ago, a stream or waterway ran down to this site, providing fresh water. In a conversation with Seu Chiquinho’s son, he found a second photo that clearly shows the Casa do Porto at the Canal.

Figure 2: Port House viewed from within Marambaia, near the mangrove. Vendinha Street is visible behind.

Source: Photograph from "Barra de Guaratiba e a II Guerra Mundial" - Siqueira (2009).

Figure 3: Workers disembark at Marambaia for bridge construction; Port House is visible in the background.

Source: Photograph from the Serqueira family’s personal collection.

Chiquinho’s writings and oral histories are full of evidence pointing to the role of the Casa do Porto in sustaining slavery and the flow of strategic goods across the Atlantic. I invite the reader to imagine how crucial a stone structure was, before any quarry existed in the region, in the 16th and 17th centuries. Especially in an unstable context of rebellions, enslavement, foreign invasions, pirate attacks, and so forth. A good example is the 1710 French invasion by the corsair Jean François Du Clerc, which began in Barra de Guaratiba with the support of the Tupinambá people. The importance of a stone house in a colonial war context cannot be overstated. Even the army, in the 20th century, repurposed the mansion as the operations center for bridge construction.

In her thesis, Mota (2009) states that Guaratiba was awarded to Manoel Veloso Espinha as a prize and recognition for the so-called “indigenous captures”, military expeditions against the local Tupinambá. Citing Fragoso (2001), she notes that the first sugar mills in Guaratiba relied on “native slaves” to accumulate capital, including through the sale of this labor. Espinha had migrated from São Vicente, the main hub for indigenous trade in Brazil. Mota highlights how the land disputes underscore the value of coastal areas.

The settlement is explained by the productive use of such areas, for instance, the fact that soils near rivers are more fertile; they offer water sources for the mills; fishing is possible; and they allow for the construction and control of docks for transporting goods. Control over these areas often meant economic advantages for landowners, especially in overseeing the small ports connecting the region to the city’s central market. (Mota, 2009, p. 153)

As Mota (2009) notes, intense agricultural activity began early in the colonization of the Freguesia de Guaratiba, making it the area with the most sugar mills alongside Irajá. It is highly likely that Bacalhau Canal was in use, an estuary entrance with depth, a favorable spot for unloading enslaved people and other goods. A population map from 1797, analyzed by Machado (2015), shows that 58.8% of the population was enslaved. Guaratiba had the highest number of sugar mills, around 14 mills with 6,675 enslaved individuals producing sugar and cachaça. These enslaved people most likely arrived by boat, unloaded at ports. The tons of sugar produced in those 14 mills by thousands of enslaved workers certainly weren’t transported by road.

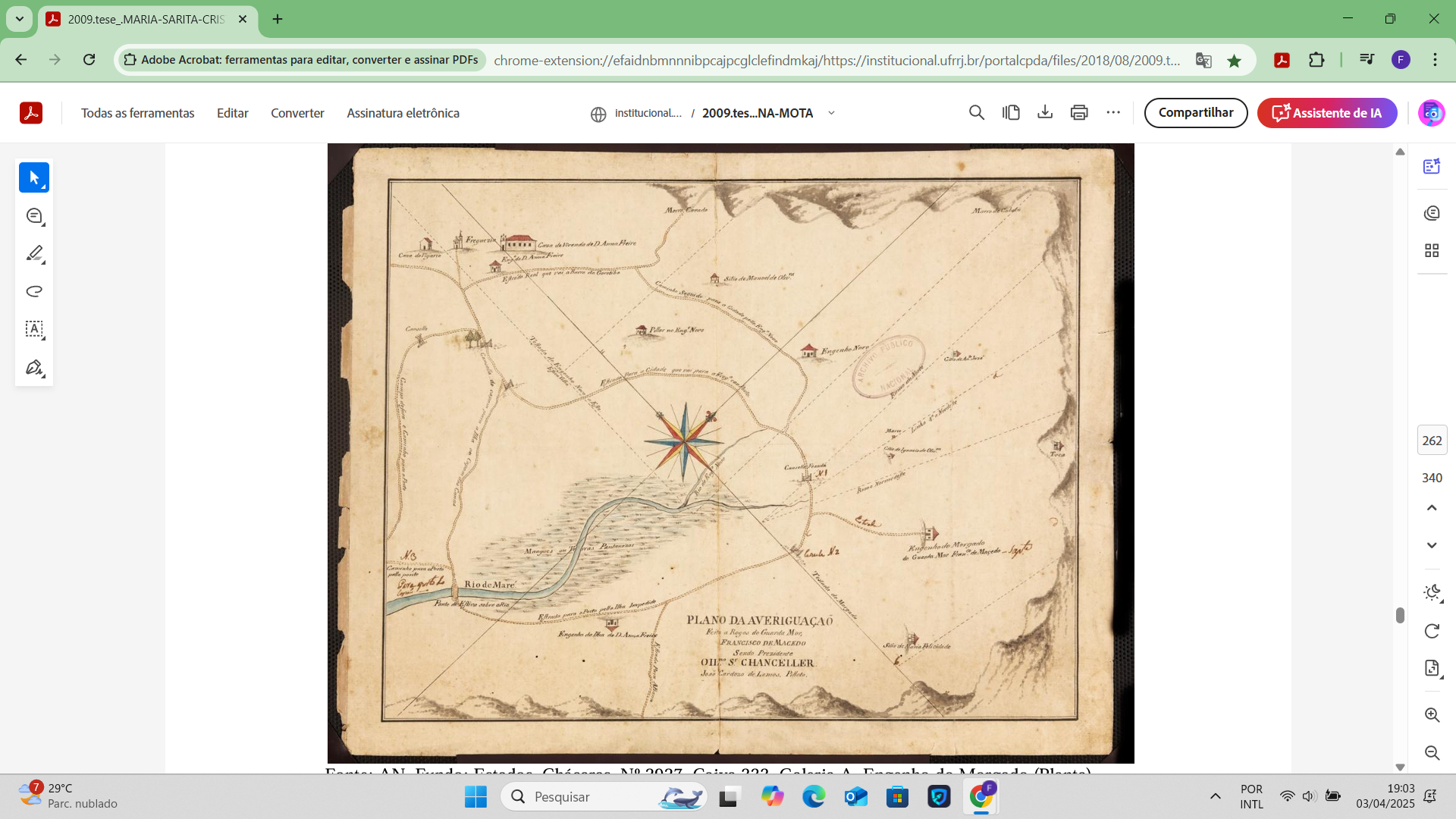

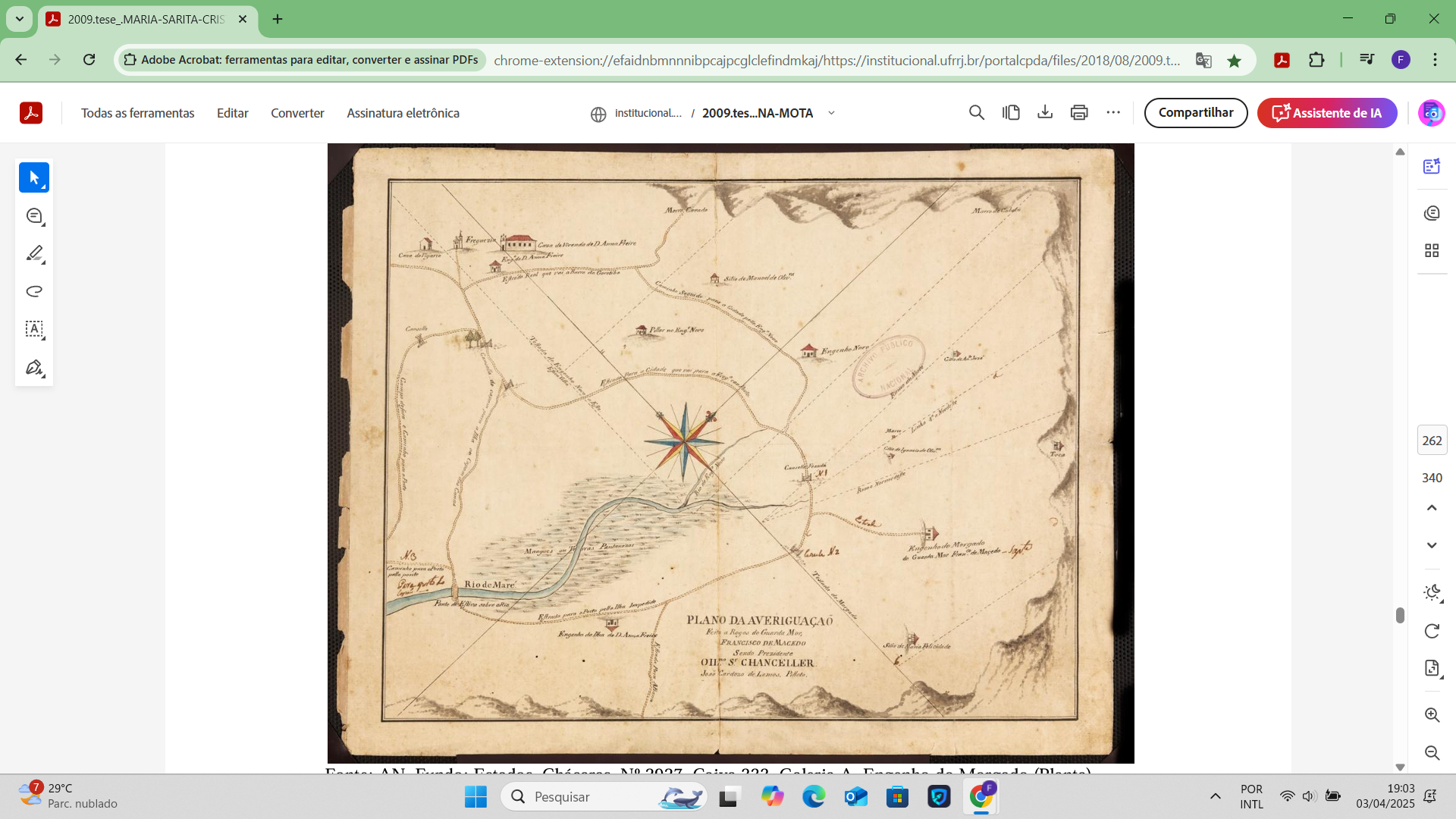

From the 16th to the 19th century, Guaratiba remained isolated by poorly accessible roads, which made land transport of its many goods unfeasible. Maritime transport was therefore the main method used. In Guaratiba’s urban memory, the existence of navigable rivers such as the Piraquê River—stretching to the Freguesia de Campo Grande—has been erased. Mota (2009) discusses a land dispute between Francisco de Macedo Vasconcelos, owner of the Engenho do Morgado, and D. Ana de Sá Freire. Without access to the sea, Vasconcelos used the neighboring estate’s land to export his goods, until an agreement allowed him access to the sea through Barra de Guaratiba. As the author states: “Ports and docks were rented by sugar mill owners for the transportation of sugar, cachaça, and other foodstuffs.” (Mota, 2009, p. 261)

Figure 4: Map of the Barra de Guaratiba region and present-day Ilha de Guaratiba.

Source: Extracted from Mota’s thesis (2009), available at the National Archives.

In the documentation of this agreement between mill owners, a map was produced showing the Engenho do Morgado, located in the Ilha de Guaratiba neighborhood, and the Engenho of D. Anna Freire, near the sea in Barra de Guaratiba. The map marks the disputed access point, near what’s labeled “Tidal River,” close to “mangroves and swampy lands.” This exit point to the sea matches all the features of the Casa do Porto area: estuary entrance, connection between open sea and mangrove.

Mota (2009), while analyzing the land grant to the São Salvador do Mundo parish, highlights this passage: “it is known that the estate was composed of 430 fathoms of frontage, extending from the Figueira Port to Barra de Guaratiba (Picão).[1]” The territorial marker of Figueira Port underscores the importance of sea access. Moreover, this 1750 letter shows that port infrastructure was already present in the region from the early stages of colonization.

These port structures became even more crucial during the so-called Second Slavery, due to the ban on the transatlantic slave trade. The Second Slavery period is tied to the coffee boom in the 19th century. Historian Dale Tomich (2011) argues that the 19th century saw an exponential increase in slavery in places like Cuba, Brazil, and the American South. While European industrialization was interpreted by thinkers such as Karl Marx and Adam Smith as the antithesis of slavery, Tomich (2011) asserts they were part of the same economic process. Tobacco, sugar, coffee, and cotton from New World plantations formed the economic base of industrial production.

From Sugar to Coffee

Tomich’s (2011) perspective helps clarify that the coffee production cycle in Rio de Janeiro, based on enslaved labor, was not an economic system in decline but rather a thriving investment driven by strong european demand, boosted by the expansion of the Second Industrial Revolution. Brazil’s second slavery was modern, capitalist, and globalized, developing in parallel with Brazilian liberal capitalism. As Santos (2022) shows, the legal modernization of the Brazilian Empire, through the Constitution of 1824 and the Penal Code of 1830, adopted liberal forms and language to preserve a development model grounded in slavery.

Tomich (2011) argues that slavery was not a doomed institution fading away “naturally,” but a foundational component of modernity. Its abolition came primarily through the efforts of abolitionist movements. Ynaê Lopes dos Santos (2022), in her article, demonstrates how, after Brazil’s independence in 1822, the Brazilian elite chose to preserve slavery. According to her, the 1824 Constitution and the 1830 Penal Code clearly reveal that the Brazilian state acted as guarantor of the slave/master relationship within a “liberal” model in which the enslaved were regarded as private property, coexisting seamlessly with wage labor. As she states:

This approach consolidated itself throughout the early years of the Empire of Brazil, not least because the number of enslaved people grew exponentially, both in urban and rural areas. This growth was a direct consequence of another measure the Brazilian national state took to reinforce slavery: ensuring broad access to slave ownership. (Santos, 2022, p. 73)

Augusto Malta, the legendary photographer and first official photographer for Brazil’s public administration, captured the mansion before construction began on the first bridge in the 1930s.

Figure 5: Photograph of Casa do Porto.

Source: Photo by Augusto Malta – Museum of Image and Sound, Rio de Janeiro.

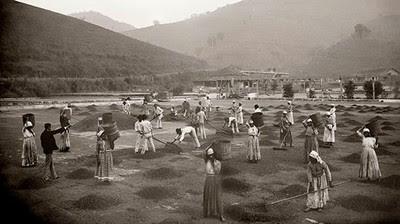

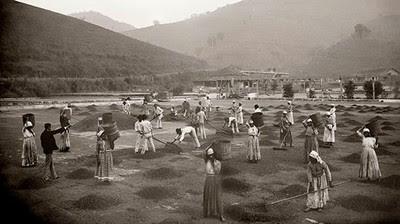

During his tenure as a photographer tasked with documenting municipal projects, Augusto Malta photographed the mansion before it was modified by the army into an operations center for the construction of the first bridge over the Bacalhau Canal. A few decades earlier, in 1882, photographer Marc Ferrez had photographed the coffee plantations of Vale do Paraíba, in Rio de Janeiro, an area belonging to the Souza Breves family, major slave traffickers. One notable aspect of the photo is the architectural resemblance between Casa do Porto and the mansion recorded in 1882 in the Coffee Valley.

Figure 6: Enslaved people working in a coffee plantation.

Source: Marc Ferrez, photograph in the Moreira Salles Institute collection.

Figure 7: Same photograph by Marc Ferrez, zoomed in.

Figure 7: Same photograph by Marc Ferrez, zoomed in.

Source: Available in the book by Thiago Campos Pessoa (2015).

The tiles, columns, verandas, and overall structure bear a striking similarity to the one captured by Augusto Malta. These images and the various layers of ruins support the hypothesis that Casa do Porto was used in multiple phases of Brazilian slavery, from the colonial period through to the so-called second slavery of the Empire.

As Pessoa (2015) points out, coastal shipping structures for exporting coffee from Vale do Paraíba after 1830, when key ports like Valongo were closed, were widely repurposed for illegal slave trafficking. There was a continuous process of adapting these stone-built infrastructures for that purpose:

“In the Fluminense region, dozens of ports were built from Paraty to Guaratiba, at the crossroads of coffee exports and clandestine African landings. (…) By the mid-1830s, with the closure of traditional disembarkation ports in the province, such as the famous Valongo market, structures originally built to support coastal trade began to be repurposed for large-scale slave trafficking across the Atlantic.” (Pessoa, 2015, pp. 1–9)

According to De Carvalho (2012), landing enslaved people required a complex infrastructure, initially centered in large urban areas. These locations provided access to clean water, medical care, food, and state-protected security. However, when operations shifted to remote regions, new factors became critical: the selection of beaches, the presence of natural estuaries, and the availability of preexisting infrastructure were essential.

Moreover, clandestine landings gave rise to a parallel economy of services and commerce. These included hiring sailors for naval maneuvers, using canoes and small vessels to guide ships to the coast, and organizing holding areas to separate sick from healthy captives. These places also served as temporary jails, requiring access to water, food, medicine, and even multilingual intermediaries to manage the reception and classification of enslaved individuals by skill.

This system, developed over more than three centuries, adapted to secrecy but became increasingly vulnerable. Any logistical failure such as lack of clean water, medicine, food, or exposure to military forces, could result in the death or “theft” of all captives, representing a significant economic risk to traffickers. Finally, the chosen location also needed to allow for quick repairs to the vessels, requiring skilled workers to ensure a fast return to open sea (Carvalho, 2015).

In short, the business was extremely profitable but also risky from a capitalist standpoint. It depended on an intricate network of resources and agents, and success hinged on logistical precision. In his article, Carvalho (2015) recounts cases where local landowners and authorities stole enslaved people from vulnerable slave ships that landed on unfamiliar shores.

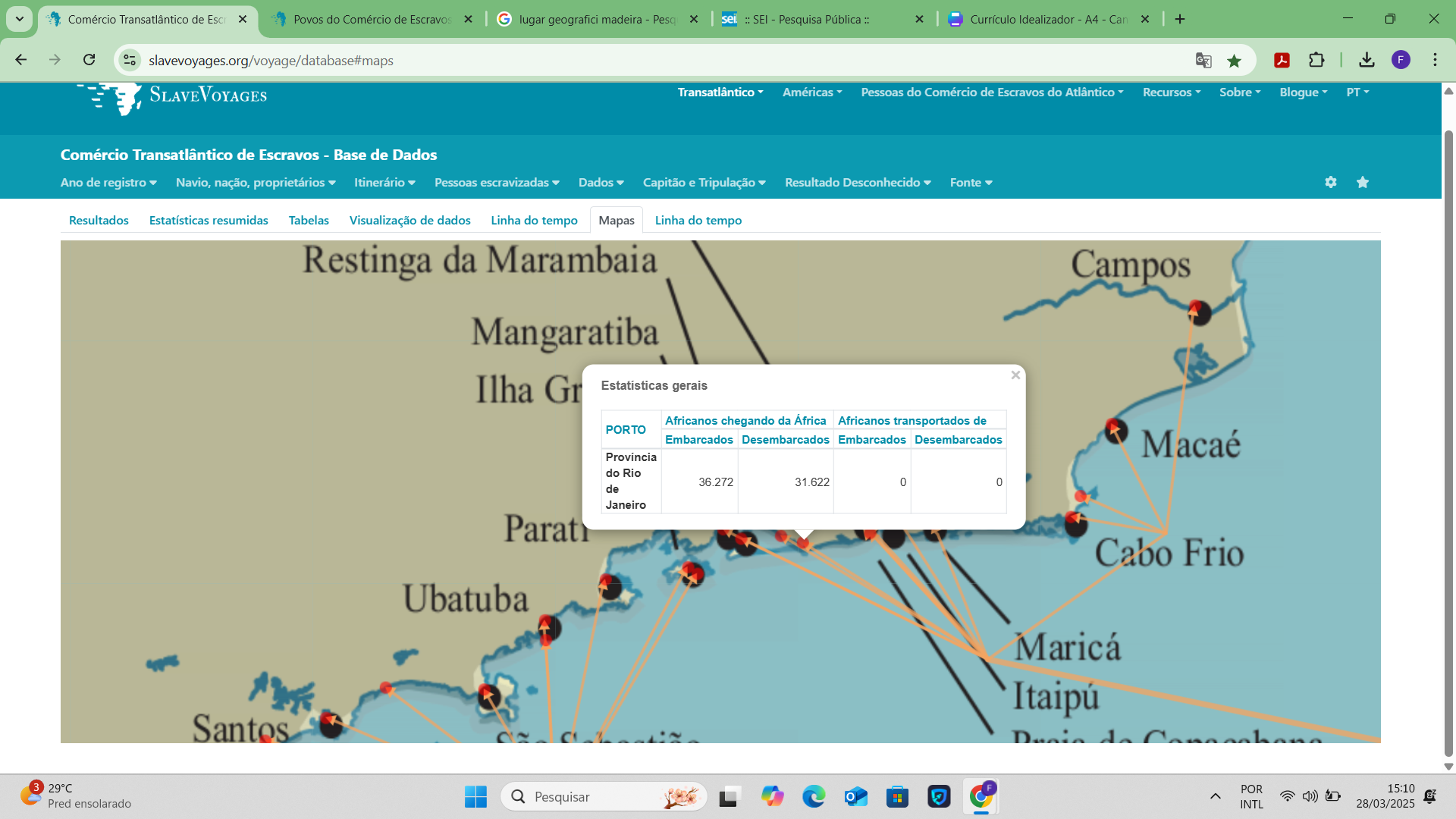

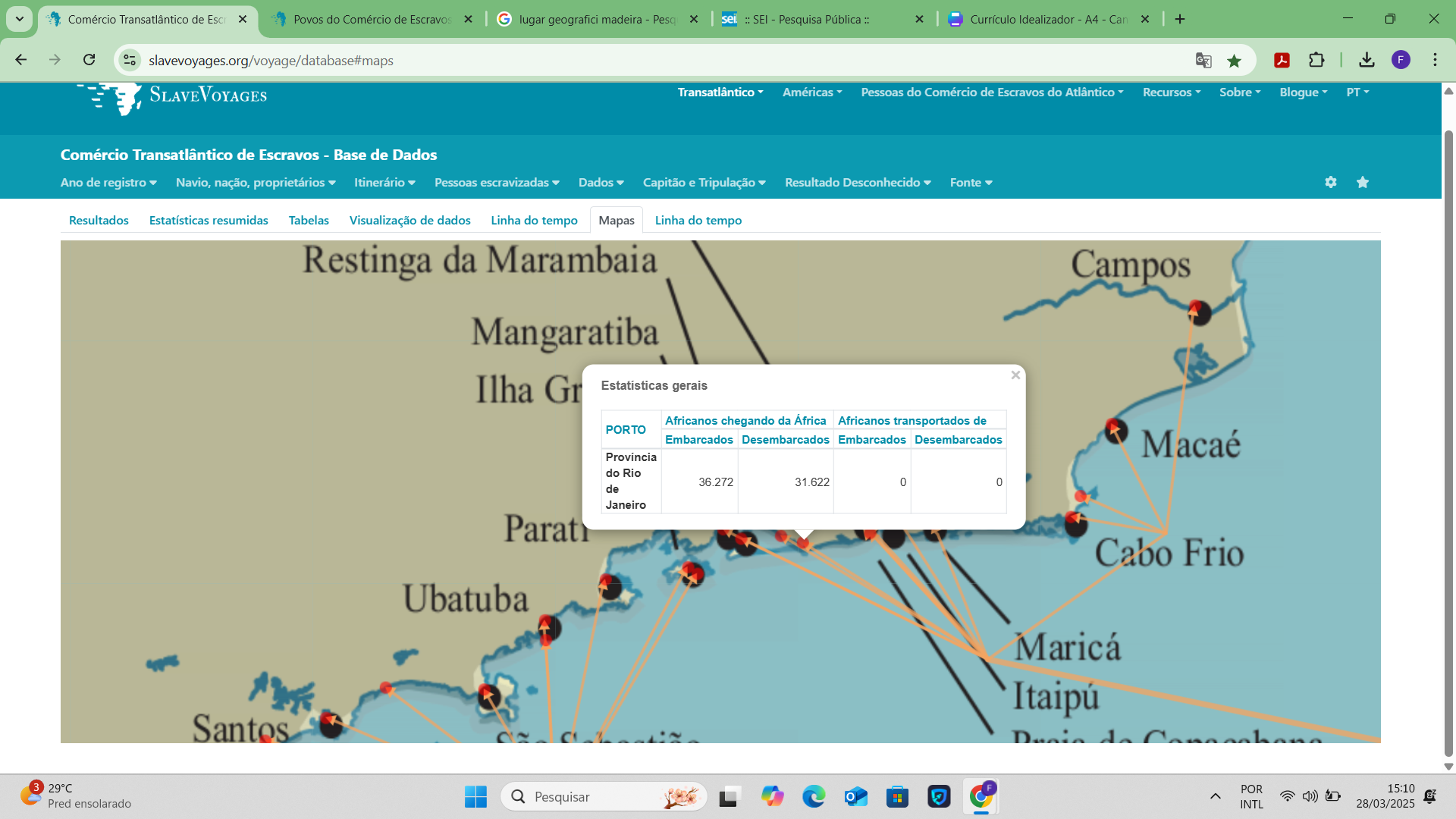

On the SlaveVoyages.org website, an extensive and interactive database documenting the transatlantic slave trade from the 16th to 19th centuries, I found a map pinpointing the exact location of the so-called “Casa do Porto,” marking the landing of 31,622 kidnapped Africans. The same map also shows a port on a mangrove island, Figueira Port, also identified by Chiquinho as a site where enslaved people were auctioned, and which later, in the 1980s, became home to the Marambaia Club.

Figure 8: Screenshot of a map showing slave trade along the Brazilian coast.

Source: Screenshot from https://www.slavevoyages.org/

The database lists ship names, captains, departure locations, number of captives, and years of voyages. The most recent voyage recorded at the site labeled “Province of Rio de Janeiro” (the same area as Casa do Porto) took place in 1850, aboard the ship Norma Júlia. It originated in Boston, purchased captives at the port of Ambriz in Bengo Province, Angola, and disembarked 308 enslaved people at Casa do Porto. Of the 342 who boarded in Angola, 34 died en route. The record states that the ship was seized by the British and the sale was thwarted. The captives were sent to the House of Correction and later forced into public labor in Rio de Janeiro. The earliest recorded voyage dates to 1716, with scant data, 228 enslaved people disembarked at Casa do Porto.

The database also allows searches for enslaved individuals by name. Only one ship arriving at Casa do Porto has this level of detail, the Brilhante, which docked in November 1837. It left Angola with 529 captives and arrived with 479. According to the British Parliamentary Papers: Slave Trade, vols. 1–90 (Shannon, 1969–74), among the 479 survivors were: Muade, a 15-year-old girl; Panda, a 9-year-old boy; Lua Cheia, a 13-year-old adolescent; and Biemba, a 20-year-old woman. Other records show the ship’s owner was José Vieira de Matos, a Portuguese man previously convicted for illegal slave trafficking and identified as an operator in Africa.

An interesting case to analyze is the patacho (a vessel suited for coastal navigation) called “União Feliz”. As Pessoa (2005) notes, it was denounced in Mangaratiba’s municipal council in 1837 for landing enslaved people in the province. The report reads:

“On January 10 (...) [1837], the patacho claiming Portuguese origin, named União Feliz, was seized by the local justice of the peace for having engaged in the illicit, immoral, and inhumane slave trade since 1835. It had just landed Africans at the location where it was seized. Involved in this ship was Joaquim José de Souza Breves, who, realizing he couldn’t bribe the justice of the peace, stormed the vessel in anger (...) which was then being held at the Fort of Guia, and sailed it again, likely to transport another shipment of unfortunate souls.” (FMP, f. 136–137 apud Pessoa, 2015, p. 12)

The report continues, naming Joaquim Breves as the operator on land, and Manoel Antônio Rodrigues as the ship’s captain. On SlaveVoyages.org, several journeys by União Feliz are documented. One includes a landing at Casa do Porto. Sailing under the Portuguese flag and captained by Rodrigues, it left Ambriz, Benguela, in 1836 with 118 Africans, disembarking 105 survivors at Casa do Porto. A year later, the vessel was seized in Mangaratiba, strong evidence of the Breves family's role in Casa do Porto’s operations.

União Feliz is an important object of study for understanding illegal slavery during the period, particularly due to the individuals connected to the vessel. Its region of origin, Ambriz, was highlighted by Angola’s governor-general in 1840 as a site where authorities were routinely circumvented to land goods and embark enslaved people. Ambriz was claimed by Portugal, and during that time, the governor-general dispatched the brig Tejo to investigate. In his report, the commander stated that he found warehouses on the beach, and receipts at the site bore the name of João Henrique Ulrich. It is highly likely that União Feliz was supplied at this base established by the Portuguese trafficker and close associate of Joaquim de Souza Breves (Pessoa, 2018).

Ulrich, in addition to his involvement in the slave trade, also extended credit to plantation owners to finance human trafficking, using enslaved individuals already in Brazil as collateral for the loans. Pessoa (2013) notes, for instance, that the Baron of Piraí owed Ulrich 29 contos de réis at the time of his estate appraisal after his death. Unsurprisingly, João Henrique Ulrich would go on to become a member of the board of Banco do Brasil, serving as interim president in 1852 and assuming the presidency in 1853. The contradiction of his rapid rise in wealth did not go unnoticed by the press of the time.

Praise be to God, João Henrique Ulrich, whom I knew in Mangaratiba polishing Joaquim Breves’ boots, is now director of Banco do Brasil! (...) And what is a thousand times more scandalous: Counselor Lisboa Serra shaking hands with that filthy pale-faced! What can one expect from a bank whose president, who should be the first to command respect, lowers himself to clasp such greasy, thieving hands? What can we expect? Only what we already know: that the cunning Ulrich has told his fellow coffee planters that all the bank’s money was at their disposal, and that was precisely why he lobbied so hard for the position. (Banco, 1854, p. 2 apud Brasil, 2023, p. 14)

After all, the pale-faced left Colonel Pereira’s estate and went to that of Colonel Joaquim Breves, where he had no other job but to run errands and accompany him on his trips, without salary, only receiving food [...] Leaving Colonel Breves’ house, he went to Ambriz, on the coast of Africa, in an illicit scheme to acquire Africans on behalf of certain interests, supposedly a “good business deal.” Such was the life of the despicable Galician J. H. Ulrich, flattering some, deceiving others, always trafficking, along with his dignified malungos, in newly enslaved Africans, until he appeared in the capital of the Empire as a big-time merchant and even a political figure, the favorite of our so-called angel of peace, the brave general who defeats armies with sword sheathed and hand in the National Treasury, congratulating those who left their umbilical cords in hell. (Barra, 1851, p. 3 apud Pessoa, 2018)

Official Letter PRRJ/PRDC No. 12759/2023, submitted by researchers to the Public Prosecutor’s Office in 2023, was a groundbreaking move in holding financial institutions accountable for their role in slavery. It makes clear that enslaved people were not only labor but also the foundation of financial capital. Enslaved individuals were used as collateral to secure loans, making slavery integral to the functioning of credit systems like Banco do Brasil. It is also essential to consider the profit that illegal trafficking generated for the credit extended at the time. With the prohibition of the transatlantic slave trade, the commerce became even more profitable. The rising value of enslaved individuals directly benefited Banco do Brasil, since loans were backed by human collateral. Moreover, the continued operation of the trafficking network clearly enabled traffickers to repay their debts, along with the corresponding interest, making slavery not only a labor system but a profitable financial engine.

Historian Ynaê Lopes dos Santos (2022) states that the Brazilian Empire was rebuilt on the profits of slavery. Banco do Brasil’s resurrection after its first collapse was funded by illegal slave trade. As she writes:

A number of historical studies point out that enslaved people were the most widespread form of property in Brazil, even among the poor. The ability to purchase a slave through credit letters made it easier for people of modest means to acquire captives and pay in installments, often using the labor of the very enslaved person whose full value had not yet been paid off. (Santos, 2022, p. 71)

Banco do Brasil, and the Brazilian state, has a historical duty to preserve, research, and disseminate knowledge about the surviving structures of the slave trade. It is essential to highlight that, in the second half of the 19th century, the bank was reestablished with capital from illegal slavery. The institution itself was built on the forced labor of thousands of Africans and their born-slave descendants on coffee plantations. Ulrich’s son would later become president of Portugal’s largest bank, Caixa Geral de Depósitos. Curiously, the bank’s website hails the Ulrichs as prominent businessmen, without a single reference to their legacy of slavery or the fortune made from exploiting Brazil and Angola[2].

Conclusion

The recognition of the historical heritage of Barra de Guaratiba, including the Casa do Porto and the Church of Nossa Senhora da Saúde, depends on the coordination between public institutions, local communities, and specialized entities. The preservation of these sites must be accompanied by actions that ensure their functionality for current generations, integrating technical studies and memory initiatives. How many families in the neighborhood descend from those kidnapped through the Casa do Porto? What does the soil of this place hide? What could the recognition and valuing of this memory bring to the neighborhood?

The article, by highlighting the existence of the Casa do Porto as a logistical site of slavery, shows that in the 19th century the institution of slavery was in full operation. The involvement of João Ulrich (former president of Banco do Brasil) in organizing a disembarkation at the site symbolically demonstrates how the illegal trafficking of enslaved people was tied to the development of global financial capital. As indicated by Pessoa (2015, 2018), illegal slave traders profited from the credit-based market of enslaved sales, using land and enslaved people as collateral. The Casa do Porto and its history present historical elements that show how the prohibition of the slave trade in Brazil was an economic strategy to maximize profits, since during the period of prohibition there was a significant increase in the flow of purchase and sale of enslaved people. The cabotage system of coffee and sugar in poorly monitored areas was widely repurposed for illegal slave trafficking, using Marambaia as a natural port of disembarkation, strategically close to the Paraíba Valley, where large coffee plantations were located.

The historical recognition of the process of second slavery sheds light on the clandestine disembarkation sites. The Casa do Porto is a material heritage site of the Second Slavery that remains poorly documented. It is difficult to quantify the number of Africans kidnapped and brought to Brazil through this territory. Far from representing the decline of slavery, Marambaia and its landing points are linked to the global consumption of coffee by the industrial European world. Illegal trafficking in Marambaia made possible the construction of the Brazilian Empire and its institutions, such as Banco do Brasil, which recovered from bankruptcy by making large profits from the increase in the value of enslaved people after the prohibition of the slave trade, while simultaneously financing clandestine voyages to purchase enslaved people on the African coast. If today the world drinks coffee, smokes tobacco, and wears cotton clothing, it is due to slave labor and plantation production in regions such as Brazil, Cuba, and the southern United States during the 19th century.

Pessoa (2015) indicates that Commander Souza Breves donated land to the descendants of enslaved people from his plantations, including Marambaia, which was “unproductive” land, previously used for the now-extinct trade. The saga of the Marambaia lands is representative of 19th-century Brazil and of Banco do Brasil’s involvement. Yabeta (2014) points out in her research that the Commander’s promised donation was not fulfilled by his wife, who sold Marambaia to the Companhia Promotora de Indústrias de Melhoramentos in 1891. This company, which belonged to relatives of the trafficker Souza Breves, went bankrupt in 1895 and was transferred to Banco do Brasil. At the beginning of the 20th century, Banco do Brasil went bankrupt, and the property was transferred to the federal government. Banco do Brasil experienced a continuous process of financial gain with the Restinga da Marambaia and the historical process of slavery, including its eventual withdrawal from the trade.

Marambaia and Barra de Guaratiba were selected during the Second Slavery because of the lack of visibility from public authorities. A century later, the same project of forgetting continues to take effect. Slavery in the peripheral territories of the city is not being told, and when it is mentioned, it is described as “a period at the end of slavery,” as something negligible. Democratizing the recognition of this period of slavery in the region helps the groups involved, quilombola and black communities in the area, develop plans for historical reparation.

Given the historical evidence of the importance of the Casa do Porto and its symbolism in illegal slavery, we point to the urgent need for: an archaeological study of the Ruins of the Casa do Porto and its surroundings, an archaeological study of the Church of Nossa Senhora da Saúde, and the development of a memory project, including a museum, infrastructure for tourist visits, memorials, and exhibitions. From the history of this crime, the Black families who live in the region, the caiçaras who resisted in the mangroves, and their descendants can gain access to social development opportunities through work in tourism, something extremely valuable given that this is already a region oriented toward tourism and in need of low-impact environmental jobs.

Can anyone imagine passing through Auschwitz as an ordinary place? Or worse, as an abandoned one? A memorial must be erected with the names of the enslaved who arrived here and, by chance, remain in the documentary records, the names of the ships, their owners, captains, and the institutions involved, to promote historical awareness of the formation of Brazil and its not-so-distant past.

References

BRAZIL. Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office. Official Letter/PRRJ/PRDC No. 8579/2024, Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Office of the Prosecutor of the Republic/RJ, July 22, 2024. Available at: https://www.mpf.mp.br/rj/sala-de-imprensa/docs/pr-rj/Recomendao_Crai_RJ.pdf Accessed April 8, 2025.

BRAZIL. Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office. Official Letter/PRRJ/PRDC No. 12759/2023. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Office of the Prosecutor of the Republic/RJ, November 3, 2023. Available at: https://static.poder360.com.br/2024/10/estudo-banco-do-brasil-14-pesquisadores-24-out-2024.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2025.

DE CARVALHO, Marcus JM. O Desembarque nas Praias: o Funcionamento do Tráfico de Escravos Depois de 1831. Revista de História, n. 167, p. 223-260, 2012.

FRAGOSO, João; FLORENTINO, Manolo. O arcaísmo como projeto: mercado atlântico, sociedade agrária e elite mercantil em uma economia colonial tardia. Rio de Janeiro, c.1790-c.1840. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2001.

MACHADO, Ana Paula Souza Rodrigues. Mapa populacional de freguesias rurais do Rio de Janeiro. O distrito de Guaratiba em 1797. Revista Brasileira de História & Ciências Sociais, [S. l.], v. 7, n. 14, p. 123–139, 2016.

MOTA, Maria Sarita Cristina. Nas terras de Guaratiba: uma aproximação histórico-jurídica às definições de posse e propriedade da terra no Brasil entre os séculos XVI-XIX. Thesis (Doctorate in History) – Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro, Instituto de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, Seropédica, 2009.

PESSOA, T. C. Sob o signo da ilegalidade: o tráfico de africanos na montagem do complexo cafeeiro (Rio de Janeiro, c. 1831-1850)." Rio de Janeiro: Revista Tempo, v. 24, n. 3, p.421-449. 2018.

PESSOA, T.C. . As dimensões do complexo cafeeiro: tráfico ilegal de africanos e segunda escravidão ao sul da antiga Província do Rio de Janeiro. In: I Seminário Internacional Brasil no século XIX, 2014, Vitória. Proceedings of the I Seminário Internacional Brasil no século XIX, 2014.

PESSOA, T.C. O Império da Escravidão: o complexo Breves no vale do café (c.1850-c.1888). 1st ed. Rio de Janeiro: Arquivo Nacional, 2018. 256p.

SANTOS, Ynaê Lopes dos. A nação embranquecida e seu passado escravista: outras leituras do Brasil. Revista do Centro de Pesquisa e Formação – SESC São Paulo, São Paulo, n. 15, p. 64–77, Dec. 2022. Available at: https://www.sescsp.org.br/editorial/a-nacao-embranquecida-e-seu-passado-escravista-outras-leituras-do-brasil/. Accessed May 26, 2025.

SIQUEIRA, Francisco Alves. Barra de Guaratiba: Sua Vida, seu povo, seu passado. Rio de Janeiro: [s. n.], 2004.

SIQUEIRA, Francisco Alves. Barra de Guaratiba e a II Guerra Mundial. Rio de Janeiro, [s. n.], 2009.

Slave Voyages. Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. 2021. Available at: https://www.slavevoyages.org/. Accessed April 4, 2025.

TOMICH, Dale. Pelo prisma da escravidão: trabalho, capital e economia mundial. Translated by Jaime A. Claramonte. São Paulo: Edusp, 2011.

YABETA, Daniela Paiva. Marambaia: história, memória e direito na luta pela titulação de um território quilombola do Rio de Janeiro (c.1850 - tempo presente). 2014. 270 f. Thesis (Doctorate in History) - Universidade Federal Fluminense, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, 2014.

About the Author

Flávio Moraes is a resident of the Western Zone of Rio de Janeiro, a social scientist, and holds master’s degrees in Comparative History and in Film and Audiovisual Studies. Since 2023, he has been conducting research on the Casa do Porto, a former disembarkation point for enslaved people in Barra de Guaratiba. Beginning in 2024, he initiated efforts to coordinate an archaeological study of the site, in partnership with Pituka Nirobe and Ivonete Pereira.

Acknowledgments

I thank Pituka Nirobe and Ivonete Pereira for their continuous support of this research. I am grateful to Beto Serqueira, son of Seu Chiquinho, for his generosity in sharing such valuable archives. I also thank Congressman Eduardo Bandeira de Mello for his efforts in making an archaeological study at the site possible. To the Rio Heritage Institute (Instituto Rio Patrimônio da Humanidade), I am thankful for the technical support provided throughout the research. And a special thank you to the Army Evaluation Center (CAEx) for making the continuation of this work possible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.M.J.; methodology, F.J.M.J.; software, F.J.M.J.; validation, F.J.M.J.; formal analysis, F.J.M.J.; investigation, F.J.M.J.; resources, F.J.M.J.; data curation, F.J.M.J.; writing—original draft preparation, F.J.M.J.; writing—review and editing, F.J.M.J.; visualization, F.J.M.J.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

About Coleção Estudos Cariocas

Coleção Estudos Cariocas (ISSN 1984-7203) is a publication dedicated to studies and research on the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, affiliated with the Pereira Passos Institute (IPP) of the Rio de Janeiro City Hall.

Its objective is to disseminate technical and scientific production on topics related to the city of Rio de Janeiro, as well as its metropolitan connections and its role in regional, national, and international contexts. The collection is open to all researchers (whether municipal employees or not) and covers a wide range of fields — provided they partially or fully address the spatial scope of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Articles must also align with the Institute’s objectives, which are:

- to promote and coordinate public intervention in the city’s urban space;

- to provide and integrate the activities of the city’s geographic, cartographic, monographic, and statistical information systems;

- to support the establishment of basic guidelines for the city’s socioeconomic development.

Special emphasis will be given to the articulation of the articles with the city's economic development proposal. Thus, it is expected that the multidisciplinary articles submitted to the journal will address the urban development needs of Rio de Janeiro.

[1] Document available in the collection Archivo do Extinto Tribunal da Meza do Dezembargo do Paço, National Archives of Brazil.

[2] The title of the article on the website of the bank Caixa Geral de Depósitos references the Ulrich family’s trajectory.

Link: https://www.cgd.pt/Institucional/Patrimonio-Historico-CGD/Estudos/Documents/Joao-Ulrich.pdf (accessed April 8, 2025).