Volume 13 Issue 2 *Corresponding author paulaalbernaz@fau.ufrj.br Submitted 30 june 2025 Accepted 25 aug 2025 Published 13 sep 2025 Citation ALBERNAZ, M. P.; CONTARATO, C., DIÓGENES, M. Impacts of industrialisation and deindustrialisation in Rio de Janeiro: an investigation in the railway suburbs of the city's North Zone.

Coleção Estudos Cariocas, v. 13, n. 2, 2025.

DOI: 10.71256/19847203.13.2.151.2025 The article was originally submitted in PORTUGUESE. Translations into other languages were reviewed and validated by the authors and the editorial team. Nevertheless, for the most accurate representation of the subject matter, readers are encouraged to consult the article in its original language.

| Impacts of industrialisation and deindustrialisation in Rio de Janeiro: an investigation in the railway suburbs of the city's North Zone Impactos da industrialização e desindustrialização no Rio de Janeiro: uma investigação nos subúrbios ferroviários da Zona Norte da cidade Impactos de la industrialización y desindustrialización en Río de Janeiro: una investigación en los suburbios ferroviarios de la Zona Norte de la ciudad Maria Paula Albernaz1, Carolina Contarato2 and Marina Guerra Diógenes3 1PROURB/FAU-UFRJ, Av. Reitor Pedro Calmon, 550 - Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro - RJ, 21941-596, ORCID 0000-0002-1975-8490, paulaalbernaz@fau.ufrj.br 2PROURB/FAU-UFRJ, Av. Reitor Pedro Calmon, 550 - Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro - RJ, 21941-596, ORCID 0009-0008-6154-8893, carolina.contarato@fau.ufrj.br 3PROURB/FAU-UFRJ, Av. Reitor Pedro Calmon, 550 - Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro - RJ, 21941-596, ORCID 0000-0002-9669-7214, marina.diogenes@fau.ufrj.br

AbstractThis paper researches the impacts of industrialization and deindustrialization on the railway suburbs of the North Zone of the city of Rio de Janeiro throughout the 20th century, focusing on industrial remnants considered promising for urban transformation. It seeks to understand the opportunities the remnants offer for addressing current metropolitan challenges through the historical meaning and references they express. It adopts a multi-scalar approach, incorporating geoinformation, social history, and socio-spatial microanalysis. The analysis highlights patterns of location, conditions of use and integration into the distinct contexts of industrial remnants during periods of industrial expansion and contraction, pointing to possibilities for their refunctionalization to reduce social inequalities and enhance the value of the suburban region. Keywords: industrial legacy, urban refunctionalization, railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro ResumoO artigo investiga os impactos da industrialização e desindustrialização nos subúrbios ferroviários da Zona Norte do Rio de Janeiro no século XX, focando nos remanescentes industriais como potencial de transformação urbana. Busca entender oportunidades para enfrentar desafios metropolitanos através do sentido histórico e referencial desses remanescentes. Adota uma abordagem multiescalar com geoinformação, história social e microanálise socioespacial. A análise evidencia padrões de localização, condição de uso e integração aos contextos distintos dos remanescentes durante períodos de expansão e retração industrial, apontando possibilidades na sua refuncionalização para reduzir desigualdades sociais e valorizar a região suburbana. Palavras-chave: legado fabril, refuncionalização urbana, subúrbios ferroviários do Rio de Janeiro ResumenEl artículo investiga los impactos de la industrialización y desindustrialización en los suburbios ferroviarios de la Zona Norte de la ciudad de Río de Janeiro durante el siglo XX, centrándose en remanentes industriales como potencial de transformación urbana. Busca comprender las oportunidades que estos remanentes ofrecen para abordar desafíos metropolitanos a través de su significado histórico y referencial. Adopta enfoque multiescalar incorporando geoinformación, historia social y microanálisis socioespacial. El análisis destaca patrones de ubicación, condiciones de uso e integración de remanentes industriales durante períodos de expansión y contracción, señalando posibilidades de refuncionalización para reducir desigualdades sociales y valorar la región suburbana. Palabras clave: legado industrial, refuncionalización urbana, suburbios ferroviarios de Río de Janeiro |

Introduction

From the 1930s to the 1980s, industrialization was one of the main economic modernization strategies adopted by Latin American countries, such as Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina, with the agrarian sector being relegated to a secondary role (Pradilla Cobos, 2018). The shift in the focus of government policies resulted in significant urban transformations, especially in the cities that were the targets of new investments. In Brazil, the centralization of industrial installation in the country's two largest cities, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, was prioritized. The period during which policies favoring the industrial sector in Latin America were privileged, identified as late or developmentalist industrialization, ended in the 1980s. From then on, this model went into decline in the face of global productive restructuring and the adoption of neoliberal principles, initiating a process of deindustrialization that profoundly affected previously industrialized territories.

In Rio de Janeiro, the railway suburbs of the North Zone were the privileged territories for the implementation of the industrial park during the developmentalist economic cycle. With the progressive emptying of factories, this suburban region began to concentrate industrial remnants, often invisible and devalued "in the social imagination related to the city" (Cavalcanti; Fontes, 2012, p. 12). The legacy of industrial land and real estate structures, partly coinciding with abandoned, ruined, or unproductive warehouses and factories, as well as repurposed buildings and infrastructures intended for their support, holds the potential to drive significant changes, especially in the localities where they are situated.

To address the challenge of how to act in the face of this industrial legacy and strengthen activities still present in the once-thriving industrial areas, this article analyzes the impacts of industrialization and deindustrialization in the railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro's North Zone. Focusing on the dynamics of industrial remnants as suburban socio-spatial components that reveal historical processes and contemporary opportunities for repurposing, the research assesses possibilities for addressing problems associated with historical metropolitan inequalities and exclusions.

The investigation adopts a multiscale approach, associating geoinformation, micro-spatial social analysis, and bibliographic review to understand the patterns of location, transformation, and reconversion of industrial remnants. The cross-referencing of morphological evidence and references with social history and the construction of their objects is prioritized, opening the way for an analysis of the historicity of the studied socio-spatial configurations (Revel, 1996). It is assessed that, although marked by processes of deactivation, invisibilization, and devaluation, these spaces maintain a strategic territorial relevance and can be repurposed for the benefit of local populations, provided they are integrated into public policies that are integrated, sustainable, and sensitive to the urban-social context in which they are located.

The main sources used in the research are cartographic, such as the georeferenced database of the Municipal Institute of Urbanism Pereira Passos (IPP) and the Rio de Janeiro City Hall (PCRJ), satellite images from Google Earth captured via the internet, historical maps, and cadastral and iconographic plans consulted in bibliography, on web pages, and in the digital historical collections of the Rio de Janeiro archives and the National Library, associated with census data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). Complementing the information survey are the bibliographic review (in books, articles, theses, and dissertations), surveys on web pages (especially about the studied factories) and social media (including Facebook groups of former industry employees), in addition to conversations with qualified informants.

The text is structured in chronological sections, covering: the antecedents to the industrialization policy (until 1930); the implementation of the developmentalist economic model (1930-1950); the peak of industrialization (1950-1980); the decline of the industrial sector and deindustrialization (1980-2000); in addition to final considerations that seek to provide a current overview of suburban industrialization and perspectives for the repurposing of the factory legacy. The methodology is incorporated into the introduction, and the maps and figures are presented throughout the text according to the periods analyzed.

Suburban industrial remnants: conceptual and territorial delimitation

In the context of this study, industrial remnants are defined as portions of the urban fabric where a factory establishment once existed or still exists, whose spatial and morphological traces remain visible, either through buildings, construction structures, land subdivision, or uses derived from the original function. These remnants constitute material and symbolic legacies of industrialization, operating as repositories of time and meaning in urban space (Santos, 1982). They express a coexistence in the present time of "techniques" (Santos, 2012), temporalities, and diverse moments. By remaining as an "imprinted mark [...] of past times in space," they open possibilities for current actions, "a condition for history to be made" (Santos, 1982, p. 42). Thus, they communicate and shape experiences in the present, even with deteriorated or repurposed structures, through the evocation of a social construction.

In core countries, since the late 1960s, the factory legacy entered debates about city transformations and its future (Labasse, 1966; Sassen, 1998; Soja, 2000; Zukin, 1989), integrating into academic and policy discussions in Brazil from the 1990s through the lens of industrial deconcentration in large metropolises and the growth of social inequalities, segregation, and urban violence (Lencioni, 1994; Ribeiro, 1994; Tavares, 2000). In the field of urbanism, the concern with industrial remnants, especially those emptied of their original function, led to their inclusion since the 2000s, primarily, in two strands of these debates: the first and most popular, focused on integrating industrial structures into the set of cultural heritage assets (Kühl, 2010; Rufinoni, 2020); and the second, in a reflection on what came to be called urban voids, also identified as friches urbaines or brownfields (Borde, 2006; Meneguello, 2009; Monteiro, 2020).

There are many works that relate the factory legacy to the heritage issue, emphasizing industrial typologies, cultural protection, and/or working-class memory. They usually contrast the interests of capital accumulation with those of cultural heritage preservation, and the values of capital with those of the working class (Cavalcanti; Fontes, 2012; Carvalho; Gagliardi; Marins, 2025). In the second strand mentioned, concerning urban voids, discussions around public policies or the absence thereof prevail, involving the reuse of urban voids and the urbanistic instruments for this purpose (Severini, 2019; Sampaio, 2012), with less consideration given to processes and dynamics associated with their existence.

This article aims to highlight a third, less explored strand in the field of urbanism, focused especially on the relationship between industrialization, deindustrialization, and urban transformation, which privileges the analysis of processes and urban dynamics involving industrial remnants. This analysis seeks to reinforce studies that point out the difference between socio-historical processes and their impacts in Latin America and in core countries (Pradilla Cobos, 2018).

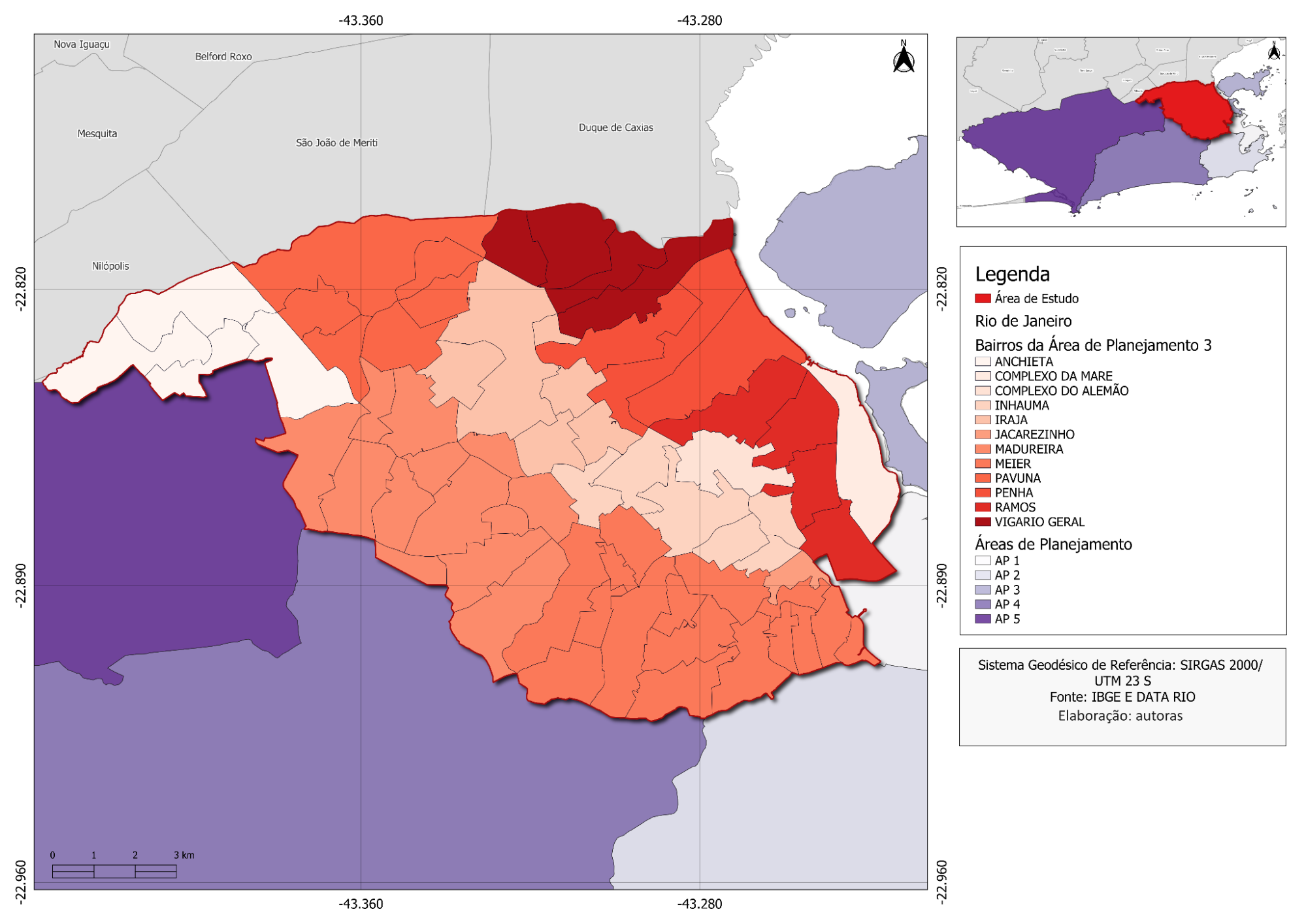

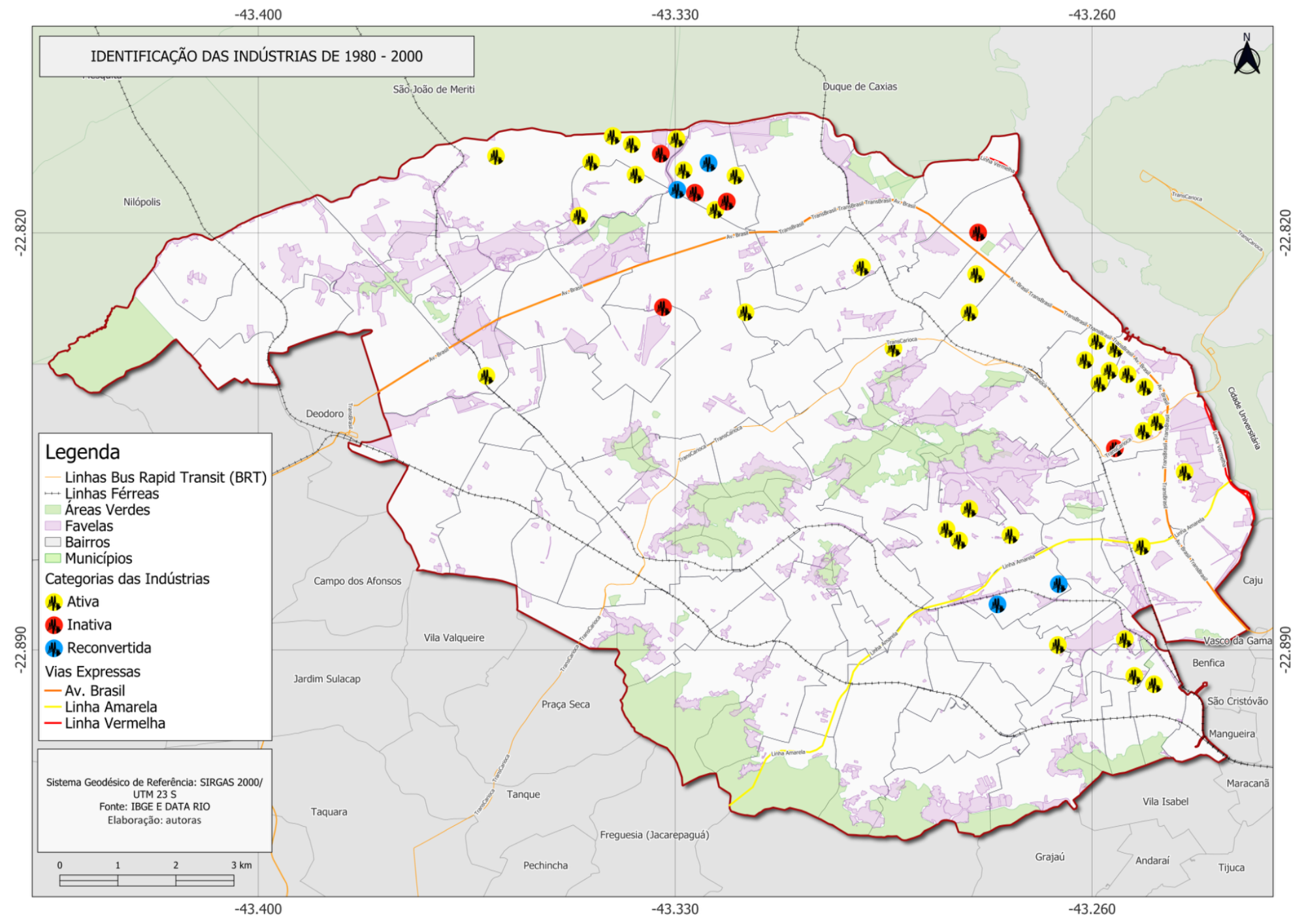

Thus, to study industrial remnants, the territorial focus is the railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro's North Zone, largely corresponding to the current Planning Area 3 (AP3) (see Figure 1). The choice of this focus is due to the priority received in many of its areas, until the late 1970s, for industrialization, and since then being in a growing process of deindustrialization. In this sense, the temporal framework established for the analysis covers the most significant years of industrialization in the studied territorial area: from the 1920s to the 2000s, aiming to encompass the repercussions of both processes on the socio-spatial structuring and configuration of the city.

Figure 1: Location of the railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro's North Zone, analyzed territorial area.

Source: IBGE (2022) and Data Rio - IPP/PCRJ (2024), prepared by the authors' research group (2025).

The diversity of situations observed in the analyzed territorial area demanded a more precise categorization of industrial remnants, in order to guide their analysis within the considered temporal frameworks and estimate their potential repurposing. To this end, the following classification into four main categories is proposed, which are used throughout the article text:

Table 1: Industry classification categories

Category | Description | Observed situations |

Active | Factory units still in operation with continuous industrial activity, even if reconfigured | Processing industries partially or fully using original facilities (chemical, food, metallurgical, etc.) |

Inactive | Deactivated, abandoned factory structures or in a state of ruin, without current use | Empty warehouses, old factories that are walled up and functionless or deteriorating |

Repurposed | Remnants that have undergone conversion to new uses (residential, commercial, etc.) | Gated residential condominiums, shopping centers, spontaneously self-constructed occupations |

Repurposed/Inactive | Partially occupied remnants | Subdivisions of old factory installations, subdivided into plots or lots with use and empty lots |

Source: prepared by the authors (2025).

This categorization allowed not only for mapping the persistence or transformation of industrial activity but also for identifying the distinct ways in which factory space was reappropriated in the urban dynamics. From it, it became possible to discuss the socio-spatial impacts of industrialization and deindustrialization and to evaluate repurposing strategies that consider the characteristics and conditions of use of the industrial remnants.

The beginnings of suburban industrialization: factories established before 1930

The presence of large industrial establishments in the railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro's North Zone predates the developmentalist cycle that began in the 1930s. Between the early 20th century and 1930, the territory already housed large factory units, driven by changes in land use, labor availability, and railway infrastructure. The fragmentation of old rural properties in the parishes of Inhaúma and Irajá, combined with the expansion of railway lines and the motive power of rivers, favored the installation of factories on large and relatively unoccupied plots of land.

Since the first half of the 19th century, due to the loss of value in the export agrarian economy, a progressive subdivision of properties that were previously rural began in the suburban parishes closest to the central areas, especially Inhaúma. Historian Raquel Lima (2012) explains the vulnerability of these parishes in the face of transformations occurring not only in the export agro-economy but also in the growth of the city of Rio de Janeiro and the interests of urban land producers. With the shift from sugarcane cultivation to subsistence farming on the then country estates and small farms, there was also a growing reduction in the enslaved population and an increase in free men in the territories of this suburban region (Santos, 1987).

The capillarity of the rivers in its territory, serving as motive power and especially as a place for the disposal of liquid industrial waste, along with the crossing of railway lines through the suburbs since the mid-19th century, facilitating the arrival of raw materials and the outflow of production, as pointed out by Maurício Abreu (1987), constituted an important incentive for the installation of industries. Furthermore, the presence of trains motivated the start of electrical energy distribution in the region in the second decade of the 20th century and was a consumer of the production from the first large factories (Martins, 2023). In 1920, within the framework of the active population in professions in the then districts of Rio de Janeiro, despite the highest percentage of professions in industries being located in the central areas (36% of the total), the railway suburbs of the North Zone concentrated 27%[1] in the districts of Inhaúma and Irajá.

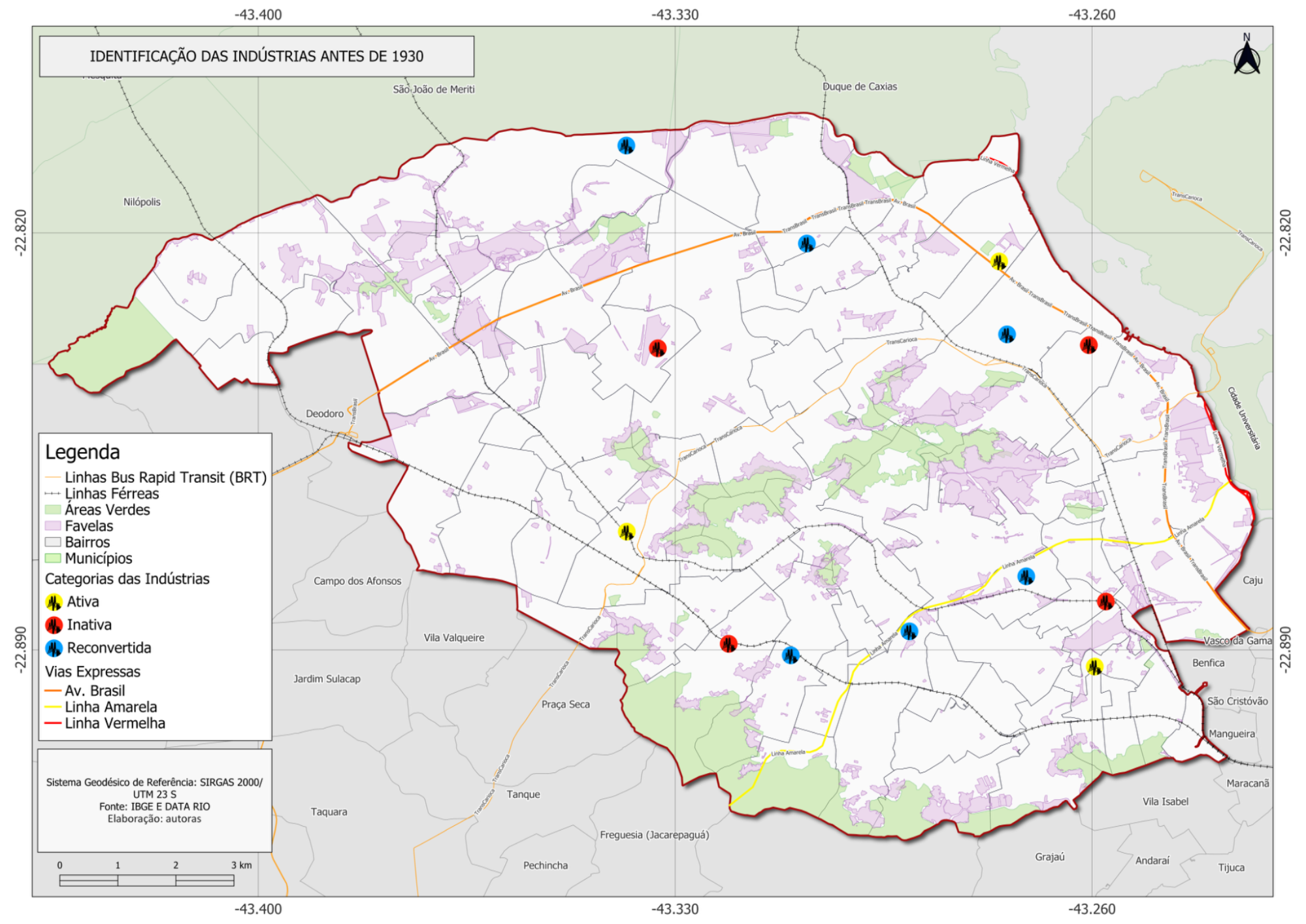

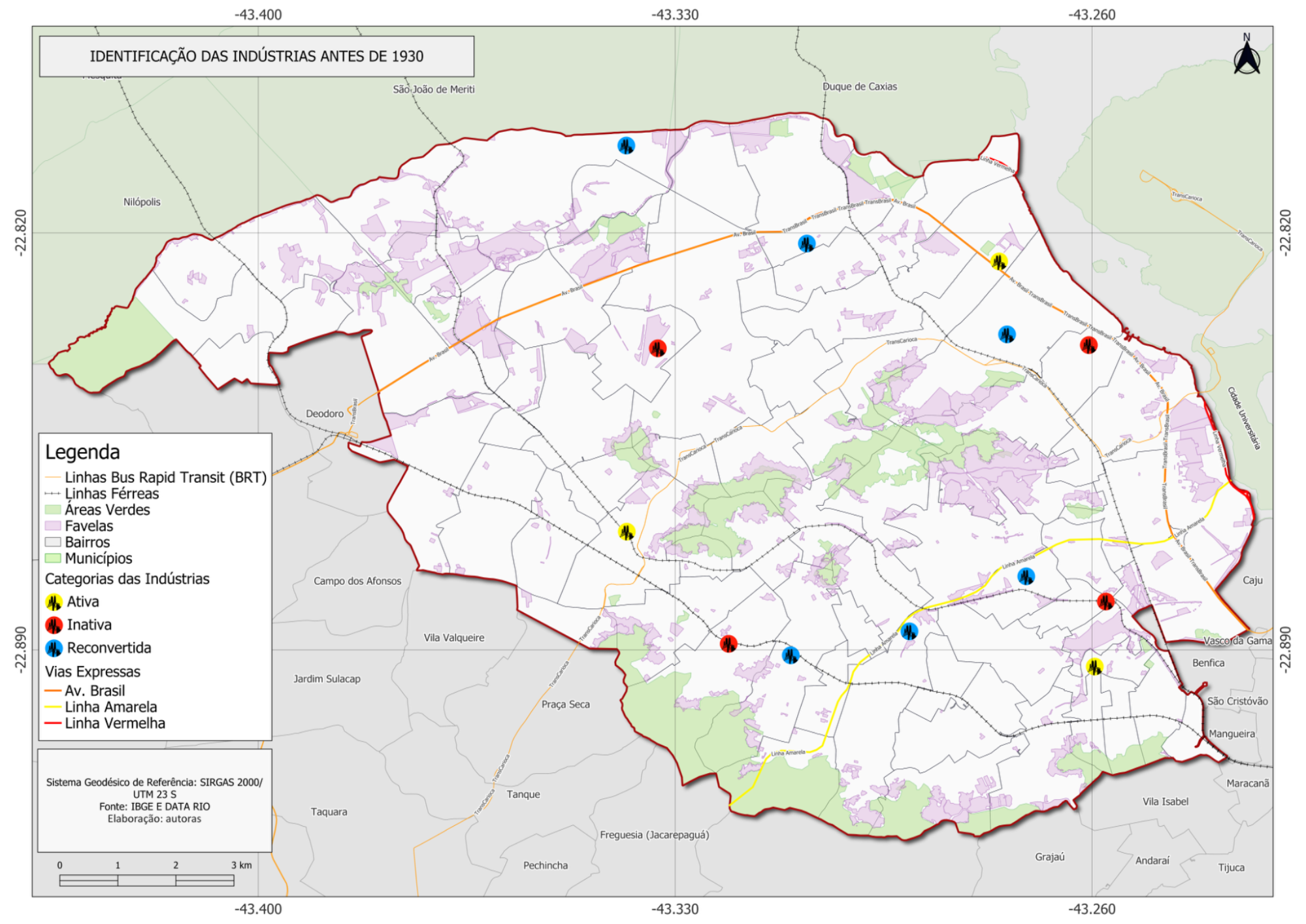

The analysis of geospatial data reveals the existence of at least 12 relevant industrial remnants dating from before 1930, representing about 5% of the total identified in AP3 (see Figure 2). These remnants, for the most part, occupy areas larger than 30,000 m², reaching 450,000 m² if the Penha Slaughterhouse is considered. This size highlights the leading role of these units in the urbanization of their surroundings and in the constitution of their basic infrastructure.

Figure 2: Map of industrial remnants inaugurated before 1930 in the railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro's North Zone

Source: IBGE (2022) and Data Rio - IPP/PCRJ (2024), prepared by the authors' research group (2025).

It is worth noting that the small factories or manufacturers and workshops in the railway suburban region of the North Zone, identified as precursors or originators of the larger ones (Martins, 2023), were not surveyed. This is because they had already disappeared over the years, leaving no traces in the urban fabric, except for those that grew or developed into large establishments.

During this period, metallurgical activities and railroad support activities predominated, in addition to textile industries, food industries, and consumer goods industries linked to the new pattern of urbanity. Two of the old factory establishments are referred to as repair workshops for railroad "rolling stock," respectively for the Estrada de Ferro Central do Brasil (EFCB) and the Estrada de Ferro Rio D’Ouro (EFRD), in the current neighborhoods of Engenho de Dentro and Engenho da Rainha (Martins, 2023, p. 40). The largest of these factories was the metallurgy and carpentry workshop of the EFCB, which had many workshops, in addition to a power plant, numerous warehouses, administration buildings, and houses for workers[2].

Although some units are still in operation, with production distinct from the original, most have been converted to residential or commercial use, such as the Nova América Shopping mall. A pattern of location linked to the railway branches is identified even in this period, highlighting the functional logic of incipient[3] industrialization.

Consolidation of the suburban hub: industrialization between 1930 and 1950

The decade of the 1930s marked the beginning of an industrialization cycle directly articulated with the national state, under the influence of the developmentalist project (Mello, 1982). Policies aimed at industrialization emerged under pressure from entrepreneurs who were already making investments or intended to invest in the industrial sector, and who had formed commissions since the end of the 19th century to demand public incentives justified by the need to bring economic independence, "progress," and "greatness" to the country (Luz, 1978).

In the context of the international crisis and the rise of the Estado Novo (1937-1945), the public sector assumed a leading role in promoting industry, providing direct incentives, infrastructure works "altering practices for granting resources and benefits" (Mendonça, 1990, p. 328), and steering the industrialization process by defining essential measures for the advancement of the economic sector and controlling many of the productive factors. The major novelty in the economy would be "the transformation of the State into a productive investor, an alternative to circumvent difficulties of the industrializing project" (Mendonça, 1990, p. 330) alongside the industrial bourgeoisie.

Brazilian industrialization strengthened, sustained by the idea of the requirement to propose innovative and centralizing solutions for the country (Ribeiro, 2000) with the aim of dynamizing the national economy. Rio de Janeiro, being the federal capital, possessing the largest urban infrastructure, available labor force, and a more efficient internal market since the 1930s, was one of the two poles for the concentration of investments in the industrial sector, with the railway suburbs of the North Zone being prioritized for industrialization.

From then on, the suburban region became the target of significant urban interventions to favor the installation of industries. This resulted in the land reclamation of mangroves and coastal beaches in the area that came to be called Manguinhos, motivated by the creation of an industrial neighborhood (Costa, 2006), and the inauguration of Avenida Brasil in 1946, still the largest urban highway in the city today, connecting Rio de Janeiro to other Brazilian capitals and linking the nascent industrial hub with the fronts of the national internal market, enabling new ventures.

During this period, the 1937 urban zoning ordinance introduced, pioneeringly, industrial zones in the city, concentrating them in the northern portion (Albernaz; Diógenes, 2023). Until the 1950s, the industrial zones increased in number and extended, encompassing "strips along the railway lines and the recently inaugurated Avenida Brasil" (Albernaz; Diógenes, 2023, p. 13), creating an internal differentiation within the suburban North Zone itself.

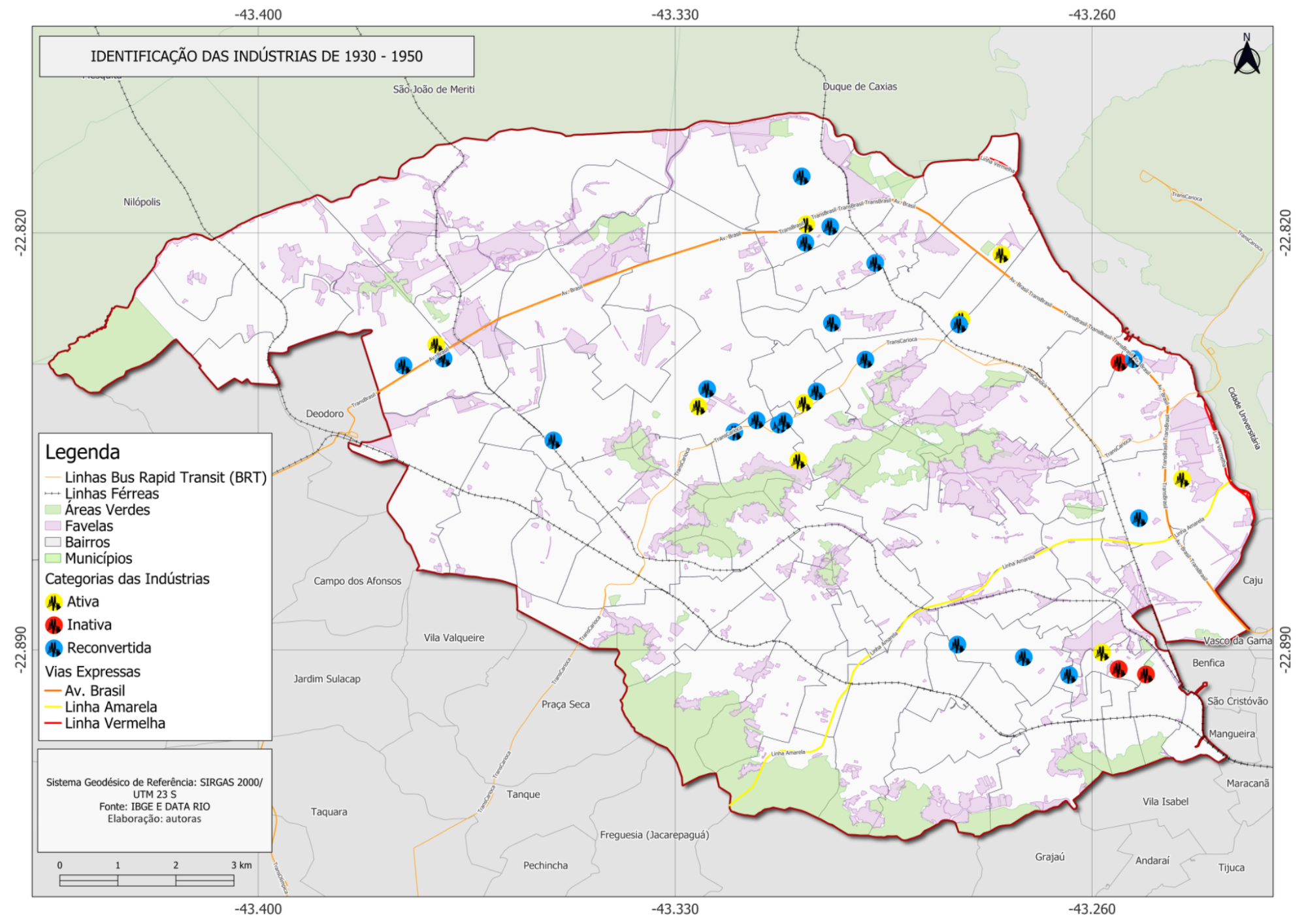

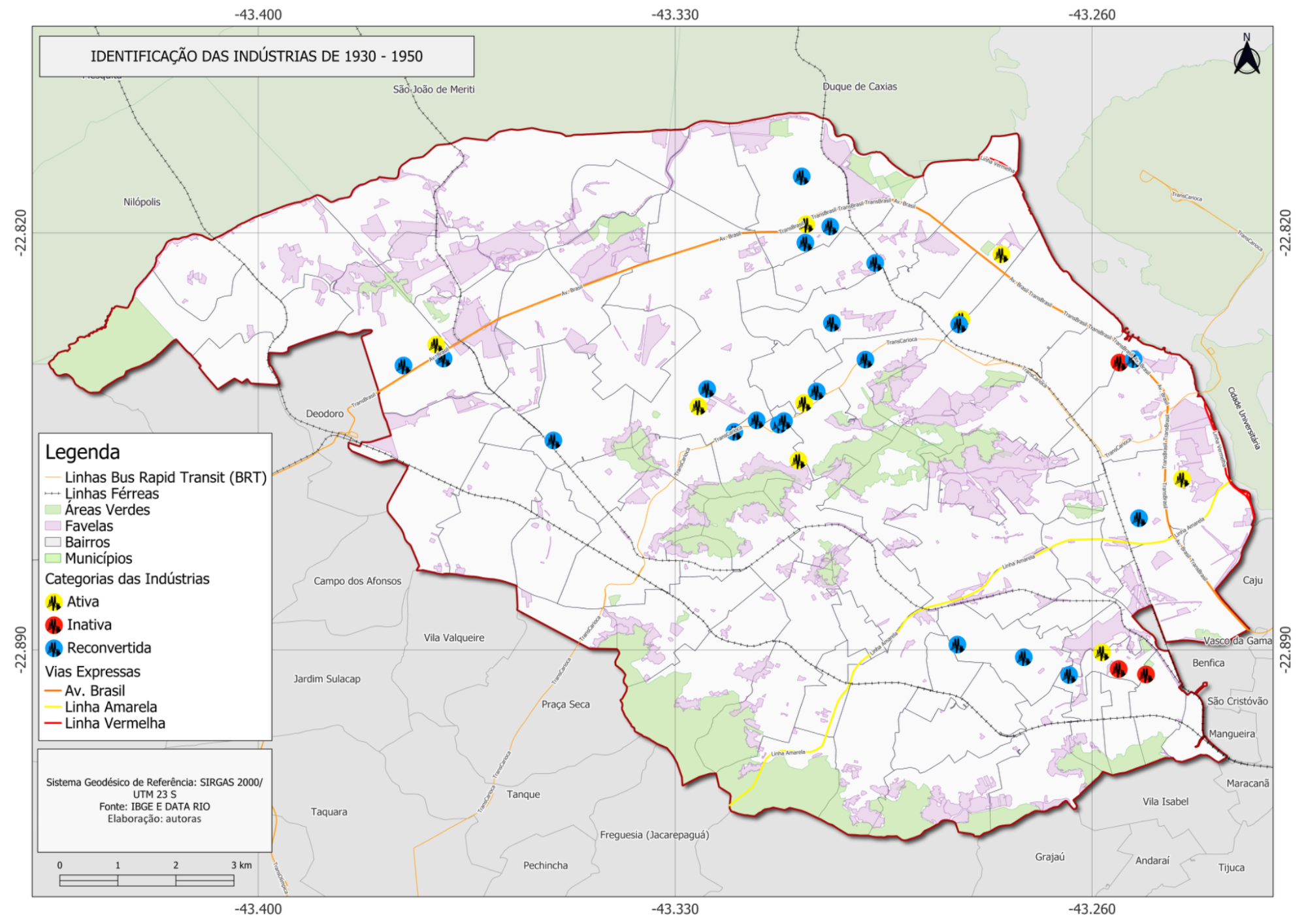

Spatial analysis of the data identified nearly 40 industrial remnants originating between 1930 and 1950, representing about 17% of the total mapped (see Figure 3). The distribution of industrial units reveals a preferential location along two road axes: following the current Vicente de Carvalho and Brás de Pina avenues, now supporting the BRT Transcarioca corridor, and mainly in the current neighborhoods of Vicente de Carvalho and Penha Circular, then sparsely occupied; and bordering the then recently inaugurated Avenida Brasil, with a greater number in the current neighborhood of Guadalupe. Some factories are still observed located along the railway branch as in the previous period, along the current Estrada de Ferro Leopoldina.

Figure 3: Map of industrial remnants inaugurated between 1930 and 1950 in the railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro's North Zone

Source: IBGE (2022) and Data Rio - IPP/PCRJ (2024), prepared by the authors' research group (2025).

An expansion of productive diversity is also observed, with an emphasis on consumer goods industries and subsidiaries of foreign companies. The industrial sectors filled gaps left in national internal supply by the difficulty of importing due to financial and political crises in core countries, as well as responding to growing demands for market novelties brought by the advancement of urbanization and changes in the social structure. In its progressive social contrast, new social groups of the dominant class emerged and the middle layers[4] grew (Abreu, 1987, p. 72-73).

From a territorial occupation perspective, large factories predominate, with lots above 20,000 m², although there is a significant presence of small and medium units. Cross-referencing factory size with inauguration dates shows that most small or medium-sized establishments were inaugurated from the early 1930s to the mid-1940s (Martins, 2023). Especially in the late 1940s, the presence of some large establishments, with 80,000 m² or more of occupied area, from foreign companies that expanded their operations to Brazil, is noted.

Reconversion is significant: about 75% of these remnants have had their function transformed, especially for the commercial sector (retail and wholesale) and for residential ventures. A quarter of the remnants remain active, albeit with changes in use or size. Overall, the period reveals a spatial pattern of industrialization strongly induced by public policies, articulating infrastructure, urban planning, and business interests. The territorial legacy of the factories installed between 1930 and 1950 still projects onto the current urban fabric, both through the built forms and the inherited economic dynamics.

- The peak of suburban industrialization: expansion between 1950 and 1980

Between 1950 and 1980, Brazil experienced the most intense phase of its industrialization, supported by national-developmentalist policies and the expansion of the State's role as a structuring agent of the economy. The creation of the Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico (BNDE) in 1952 and direct investments in industrial infrastructure consolidated Rio de Janeiro's North Zone as a privileged pole for the installation of large factory units. Thus, from the mid-1950s onwards, "a specific monopolistic structure that peculiarly articulated the multinational company, the national private company, and the public company" was realized (Mendonça, 1990, p. 333), coinciding with the "rediscovery" of Latin America by capitalist centers of core countries and the ability of the Brazilian State to unite the interests and objectives of international and national capital. The national-developmentalist ideology associated with the penetration of "American dream" ideals reverberates in the forms of industrialization (Mendonça, 1990, p. 333).

This process occurred alongside accelerated demographic growth in the two largest urban poles, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Between 1950 and 1970, the population of Rio de Janeiro doubled, exceeding four million inhabitants[5], driving demand for jobs and the densification of suburban neighborhoods. The combination of state incentives, labor supply, and expansion of the road network, notably Avenida Brasil, favored the implantation of new factories in previously marginalized areas or areas of low urban density.

In terms of socio-spatial effects, the intense increase in the number of people available to serve as industrial labor resulted in the emergence and growth of numerous favelas (Silva, 2005). Despite the understanding that the housing problem was a State issue, housing policies between 1945 and 1964 did not have greater reach and scope among the working class (Bonduki, 2017, p. 108). Even in the following decades, with more public investment in housing financing, most workers could not meet the requirements imposed by policies for access to housing, maintaining residence in favelas (Silva, 2008). In this sense, the 1960 census found that Jacarezinho, a favela in the railway suburbs of the North Zone, was the largest favela cluster in the city, with over 15,000 inhabitants[6].

In Rio de Janeiro, the State increased direct investments in infrastructure aimed at industrialization, especially in land reclamation along Guanabara Bay and expansion of the road network, with the opening of Avenidas 24 de Maio and Marechal Rondon, and the construction of viaducts linking the railway suburbs to Avenida Brasil (Abreu, 1987, p. 127). Urban zoning began to privilege peripheral sectors near Guanabara Bay, where the Manguinhos Refinery would later be installed, and the strip along Avenida Brasil, while excluding the more consolidated railway sections (Albernaz; Diógenes, 2023, p. 16), which were already targets of real estate market interest. This reorientation consolidated the internal fragmentation of the North Zone, separating industrial areas from popular residential zones, many of which were marked by favelization and urban precariousness.

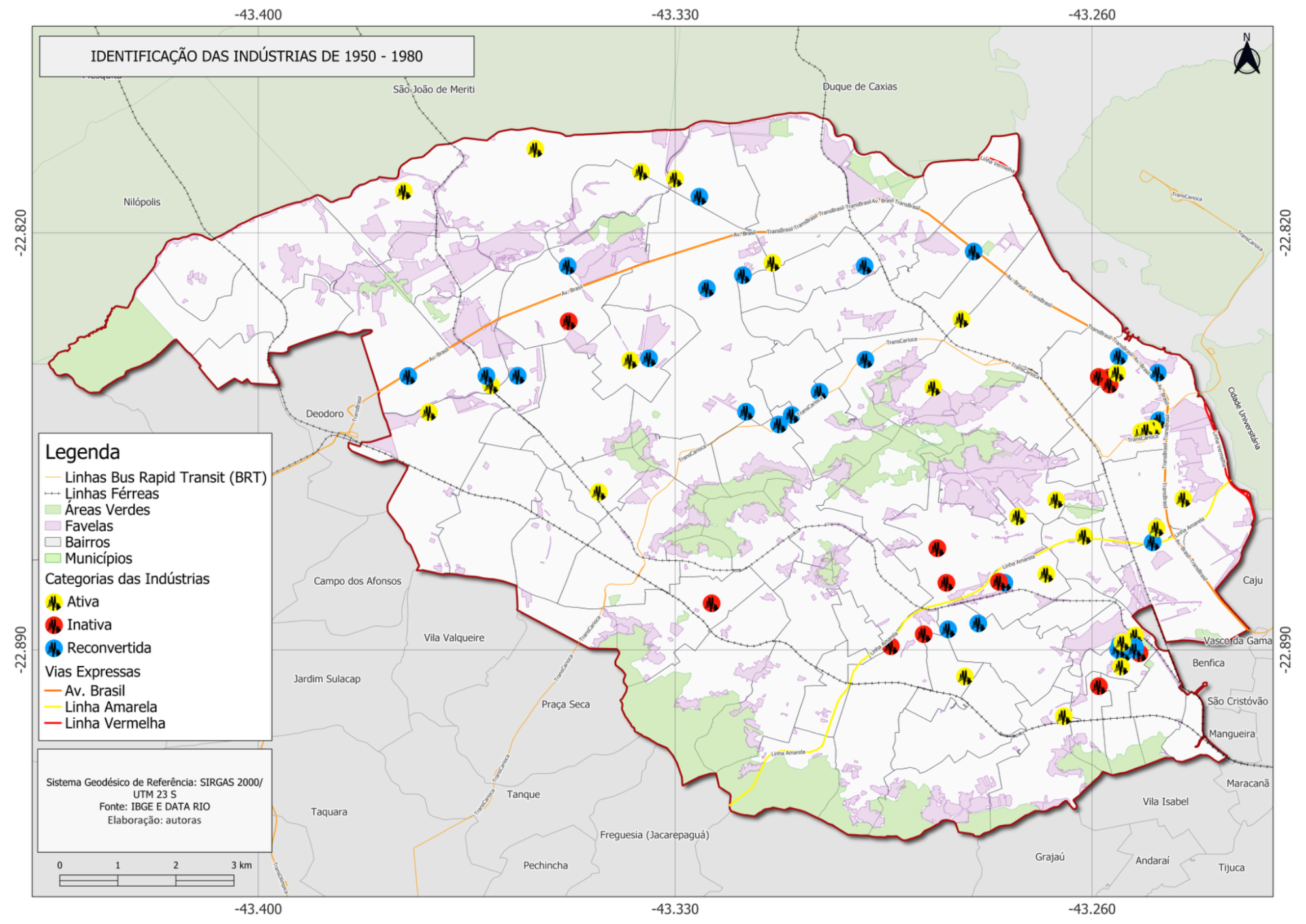

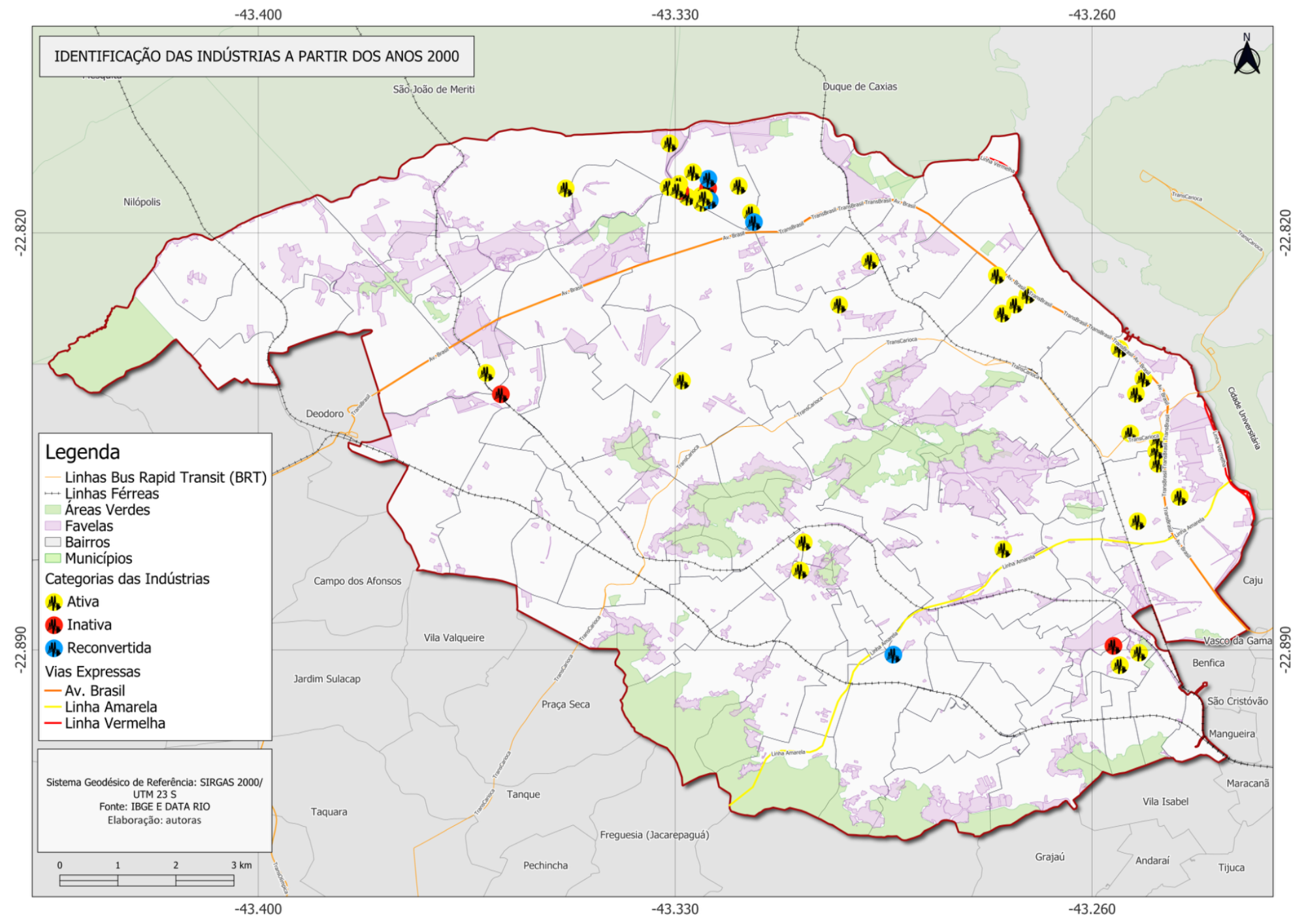

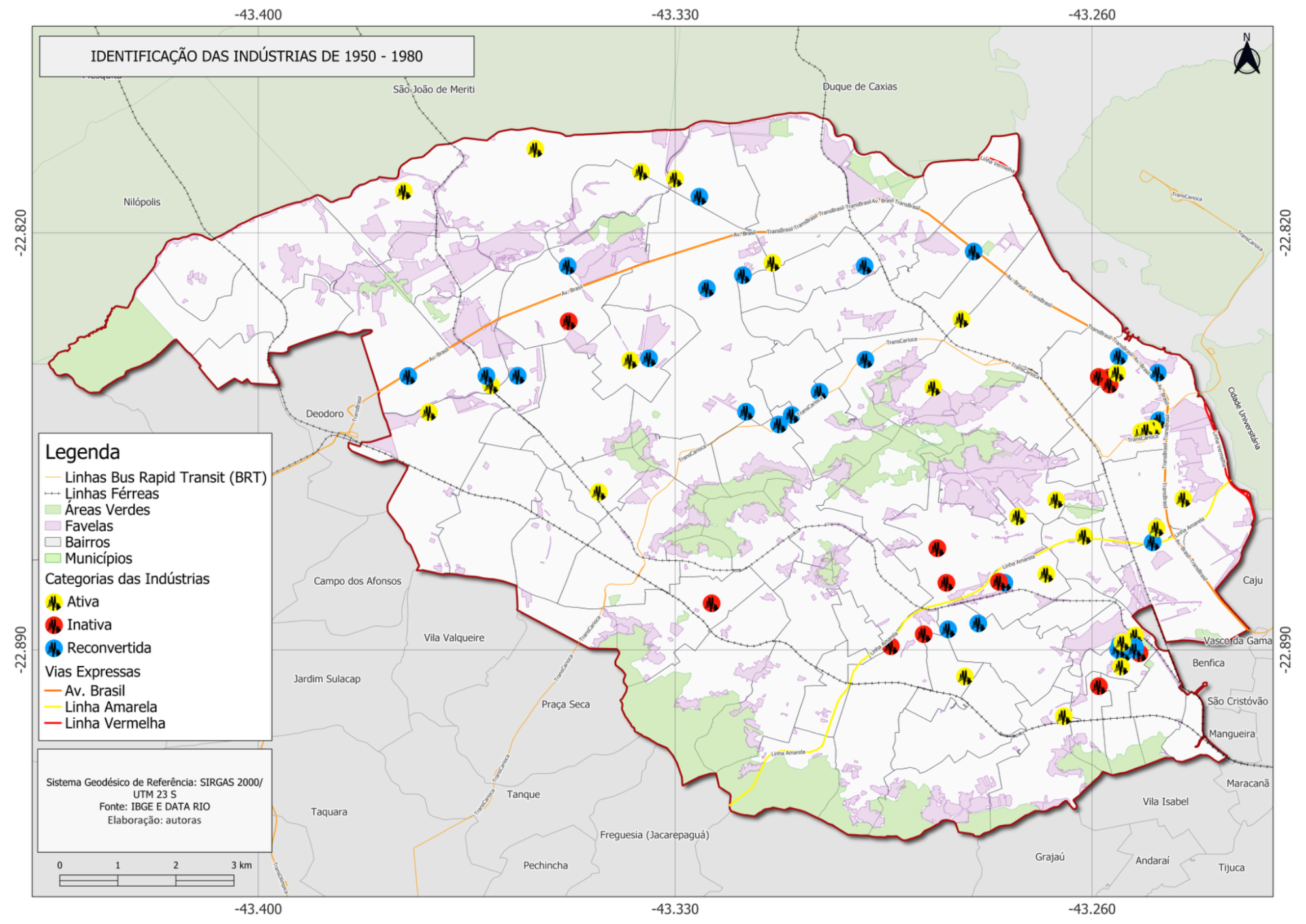

The research identified over 70 industrial remnants implanted between 1950 and 1980, corresponding to more than 30% of the total mapped (see Figure 4). This significant volume indicates the peak of the suburban industrialization process. Spatially, these factories are concentrated in areas such as Jacaré, Ramos, Manguinhos, and along Avenida Brasil.

Figure 4: Map of industrial remnants inaugurated between 1950 and 1980 in the railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro's North Zone

Source: IBGE (2022) and Data Rio - IPP/PCRJ (2024), prepared by the authors' research group (2025).

The industries installed in this period show greater diversification, both in size and productive nature: basic industries (cement, chemical, steel) coexist with consumer goods units (clothing, food, furniture), many linked to the growing demand of the urban market. In terms of production nature, the emphasis is on heavy industries, such as mechanical and machinery, cement, machining, iron and steel, and chemical products, which reproduce technological advances from core countries and correspond to investments in basic industries cited for the period (Suzigan, 1988). The industrial remnants also show the presence of some industries occupying large plots, including subsidiaries of international companies. From the 1960s onwards, there is a predominance of small factories being installed.

Despite the economic prominence of this cycle, more than half of the remnants from this period are now inactive or reconverted, especially for storage, commerce, and services, followed by housing. Notably, in this context, is the emergence of self-constructed occupations on old factory lands, revealing new forms of urban appropriation, equal in number but in much smaller areas than residential condominiums. Still, approximately 43% of the identified establishments remain active, largely with new productive vocations and in reconfigured areas.

This period demonstrates the peak of articulation between urban planning, industrial capital, and socio-spatial transformation. The territorial legacy left by this cycle remains visible not only in the landscape but also in current disputes over land use, infrastructure, and valorization.

- The decline of industrialization in the suburbs: retraction and transformations between 1980 and 2000

This new order brought effects on the spatial configuration and territorialization of factories, corresponding to the flexibilization of jobs and the priority given to new industrial poles and agglomerations (Ramonet, 1998).

From the late 1970s, an inflection began in the Brazilian industrial model, marked by the fiscal crisis of the State, global productive restructuring, and the adoption of neoliberal policies. The new context drove trade liberalization, economic deregulation, and financialization (Slater, 2011; Solimano, 1998), resulting in the progressive deactivation of factory establishments in large metropolises, especially affecting industrial sectors with production processes of higher technological intensity (Ribeiro, 2024).

In Rio de Janeiro, the effects of this process were felt unevenly, particularly in the North Zone, where industrialization had consolidated in previous decades. Deindustrialization in the railway suburban territory especially affected small and medium-sized capital goods industries and, later, consumer goods industries. Many units ceased their activities, reduced their production, or migrated to other regions of the country, seeking tax incentives and lower operating costs. This emptying directly impacted the supply of industrial jobs, aggravating inequalities by contributing to the socioeconomic decline of some areas.

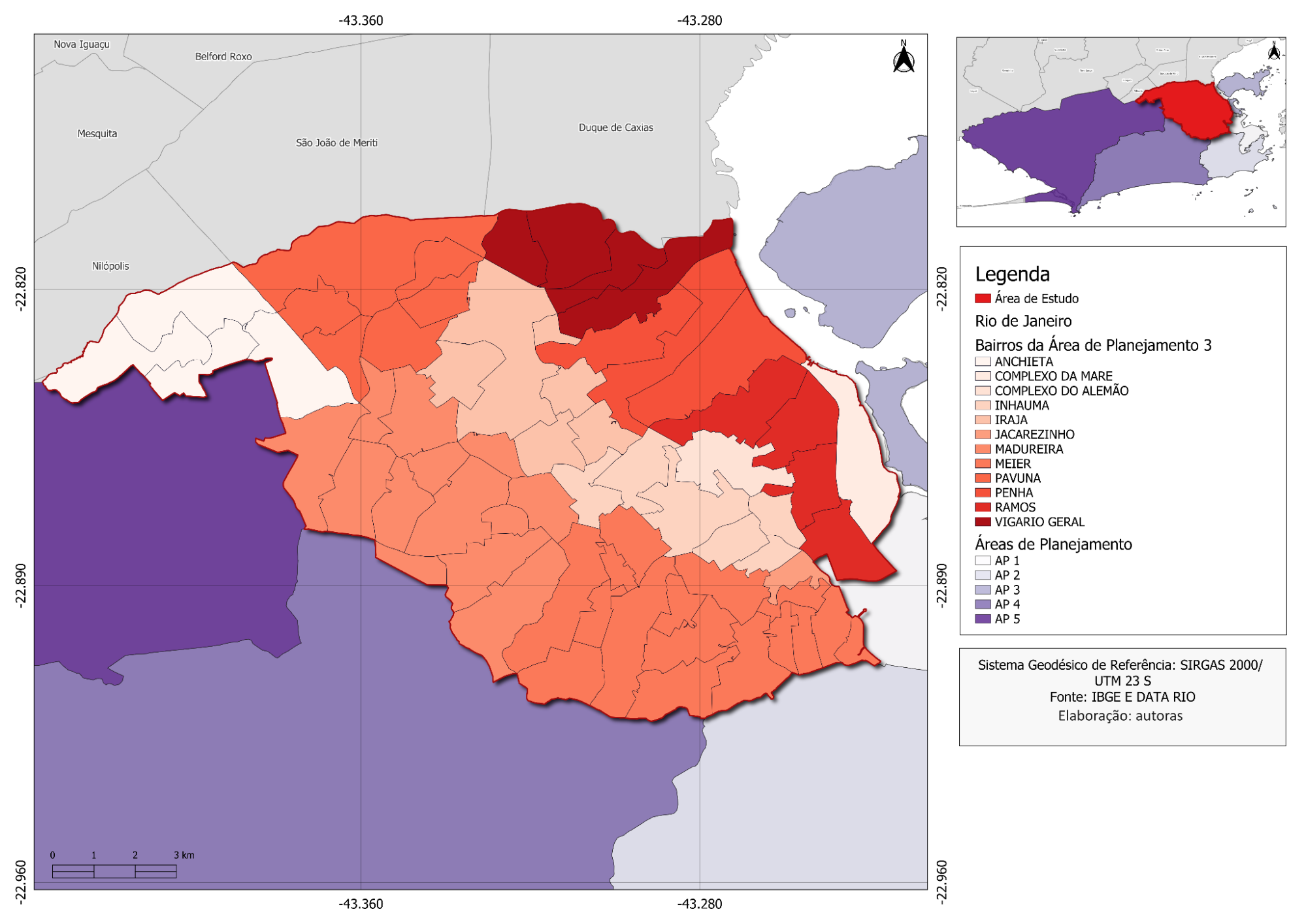

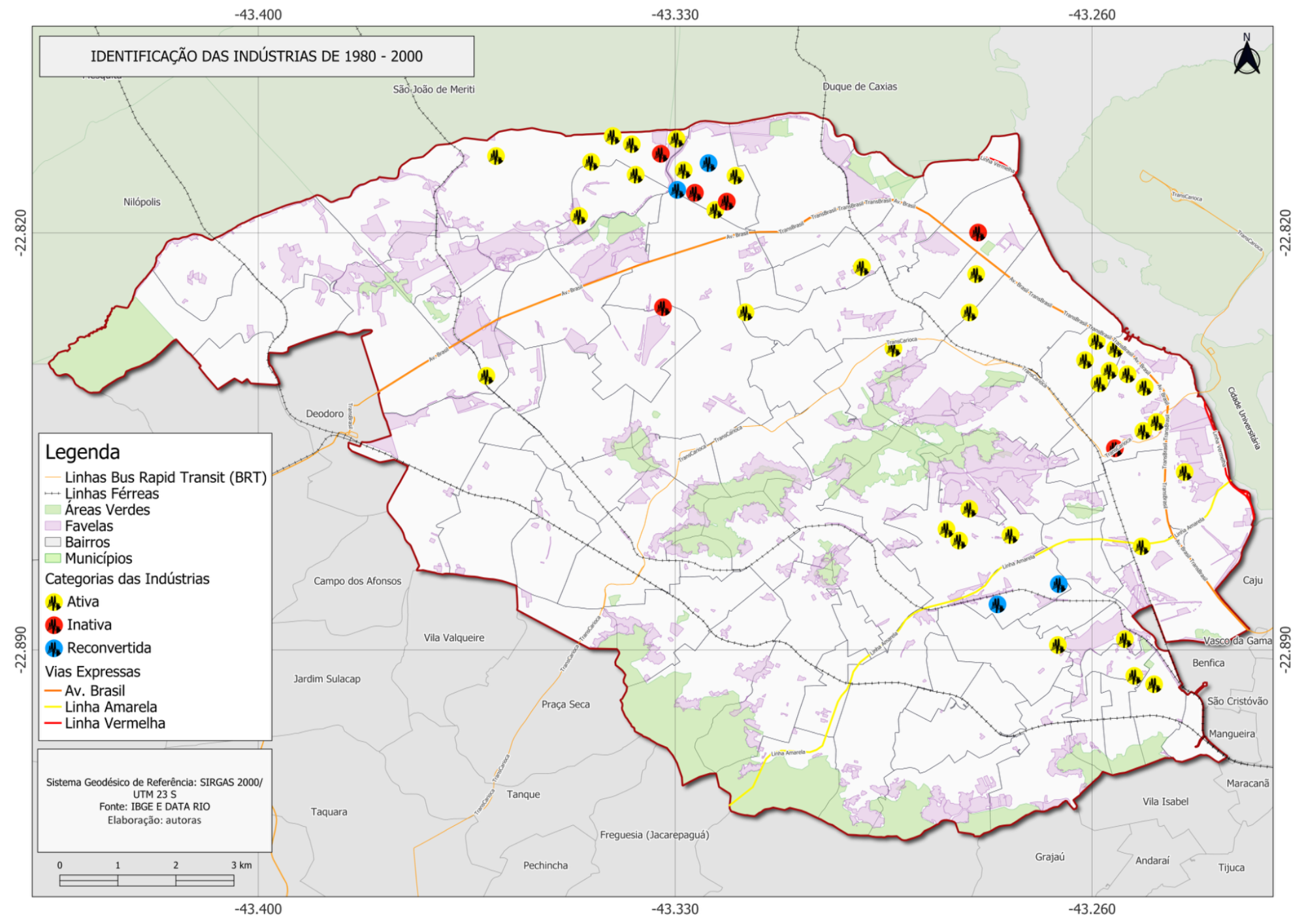

However, even in this context of retraction between 1980 and 2000, new factory installations were recorded in the railway region of Rio de Janeiro's North Zone, albeit in significantly smaller numbers. The industrial remnants from this period represent a small fraction of the total surveyed, with a predominance of small units (70%), occupying areas smaller than 5,000 m². The predominant productive nature includes sectors such as metallurgy, chemical products, food, and plastic products, with a specific highlight for Katrium Indústrias Químicas SA, installed in 1984, as the only large-scale example.

The permanence of some factory activities in this period reveals the resilience of certain productive chains and the presence of still competitive industrial niches[7]. In the railway suburbs of the North Zone, about 80% of the units implanted between 1980 and 2000 remain active, albeit partially deactivated, spreading mainly along Avenida Brasil and in neighborhoods such as Ramos, Olaria, Pavuna, and Jardim América, areas still covered by the 1976 urban legislation as industrial zones (see Figure 5) (Albernaz; Diógenes, 2023). However, the trend already revealed in the 1998 data is noteworthy, regarding the replacement of factory installations for the city's West Zone[8].

Parallel to the sector's retraction, the process of reconversion of previous industrial remnants intensified. Approximately 53% of the total remnants mapped in the North Zone had lost their factory function by 2000, with more than half being converted to residential, commercial, or logistical use, usually by real estate market initiative. The presence of self-constructed occupations on old factory lands also stands out, revealing popular appropriations amid institutional abandonment.

These data point to a profound change in the role of suburban industrial remnants: from production poles to grounds of dispute, reconversion, and territorial conflict. The deindustrialization cycle meant not only the loss of economic function but also the emergence of new logics of use and spatial fragmentation that show the coexistence between distinct ways of producing and transforming the city that make the suburbs "the mosaic of disparate forms, functions, and ways of doing and living" (Simone, 2022, p. 4).

Figure 5: Map of industrial remnants inaugurated between 1980 and 2000 in the railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro's North Zone

Source: IBGE (2022) and Data Rio - IPP/PCRJ (2024), prepared by the authors' research group (2025).

- Final considerations: permanence, contradictions, and perspectives of urban transformation

The historical and spatial analysis of industrial remnants in the railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro's North Zone highlights the complexity of the industrialization and deindustrialization processes that shaped this territory throughout the 20th century. The adopted approach allowed us to observe that these remnants constitute material records of different economic and political cycles of industrialization and deindustrialization in the country, as pointed out by authors such as Luz (1978), Mello (1982), and Mendonça (1990), reflecting productive logics, state decisions, and land disputes that left lasting marks on the suburban configuration.

At the scale of Rio de Janeiro, the factory legacy, while expressing a trajectory of expansion and decline, also offers clues to think about the future of the city. The initial hypothesis of the study, that industrial remnants can function as potential vectors of urban transformation, is confirmed to the extent that many of these spaces still retain infrastructure, strategic location, and reconversion capacity. However, this possibility runs into structural weaknesses, such as the absence of integrated public policies, the disarticulation between urban planning and social inclusion, and conflicts between real estate interests and the needs of local populations.

Of the total industrial remnants surveyed, from before 1930 to the 2000s, more than half have lost their factory function, and of these, almost 60% have been entirely converted to new uses, 14% partially, and the remainder have remained inactive. In reconversion, the action of the private initiative prevails, through the real estate market, and the change of use in old large factory establishments to gated residential condominiums, highlighting the presence of storage and wholesale commerce, the five shopping centers, and the six self-constructed housing occupations.

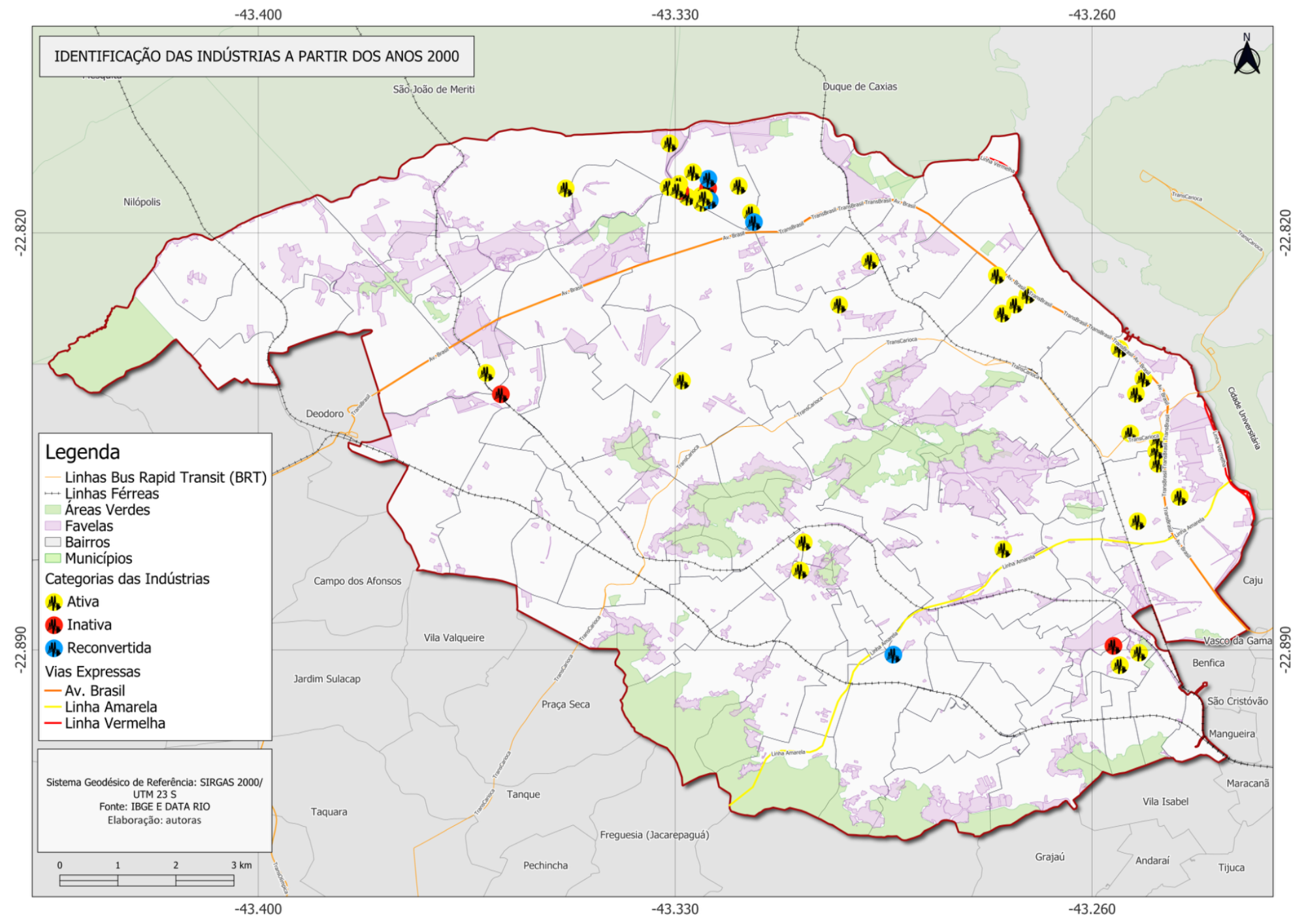

After a quarter of a century of this new millennium, it is worth reflecting on the current situation of industrial remnants in the railway suburban region of Rio de Janeiro's North Zone, considering the persistence of the industrial sector despite the de-functionalization of many of the old factories (see Figure 6). Sometimes the old industries occupy reduced areas, but sometimes these areas have also been increased. There are about 40 industrial remnants installed after the 2000s, more than 80% of the total still active, installed in small establishments, spread through areas near and along Avenida Brasil, concentrated in the Jardim América neighborhood, with very varied production natures.

Figure 6: Map of industrial remnants inaugurated after 2000 in the railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro's North Zone

Source: IBGE (2022) and Data Rio - IPP/PCRJ (2024), prepared by the authors' research group (2025).

Finally, the collected data indicate that, despite the recent diffusion of the metropolitan industrial sector, a significant industrial agglomeration persists in the Brazilian Southeast (Monteiro Neto; Silva; Severian, 2021). In the railway North Zone of Rio alone, about 110 active industrial units remain, many of them small, adapted to new productive and regulatory logics. This presence indicates that the industrial sector, although weakened, has not completely disappeared and can, on new bases, contribute to job creation, income, and local development. It is also worth considering that some of these industries are located in consolidated residential areas and should offer environmental safety and well-being to their inhabitants.

The urban transformation of the railway suburbs of the North Zone, therefore, involves recognizing the strategic and symbolic value of these industrial remnants, understanding them not as ruins of the past but as spaces of dispute and reinvention of the city, requiring a growing understanding of the economic, cultural, and social nature of their presence.

References

ABREU, Maurício de Almeida. Evolução urbana do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Iplanrio, 1987.

ALBERNAZ, Maria Paula; DIÓGENES, Marina Guerra. Impactos do planejamento urbano na localização das indústrias nas cidades: um estudo sobre o zoneamento industrial nos subúrbios da metrópole do Rio de Janeiro. Acervo: Revista do Arquivo Nacional. Rio de Janeiro, v. 36, n. 1, pp. 1-23, 2023.

BONDUKI, Nabil. Origens da Habitação Social no Brasil: Arquitetura Moderna, Lei do Inquilinato e Difusão da Casa Própria. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade - FAPESP, 2017.

BORDE, Andréa de Lacerda Pessoa. Vazios urbanos: perspectivas contemporâneas. (Doctoral Thesis). Rio de Janeiro, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Urbanismo. PROURB/UFRJ, 2006.

CARVALHO, Mônica de; GAGLIARDI, Clarissa; MARINS, Paulo César Garcez. Patrimônio cultural e capital urbano: disputas em torno dos legados industriais (Editorial). Cadernos Metrópole, São Paulo, v. 27 n. 62, p. 1-14, 2025.

CAVALCANTI, Mariana; FONTES, Paulo. Ruínas industriais e memória em uma “favela fabril” carioca. História Oral, v. 14, n. 1, 2012.

COSTA, Renato da Gama Rosa. Entre Avenida e Rodovia: a história da Avenida Brasil (1906-1954). (Doctoral Thesis). Rio de Janeiro, PROURB-UFRJ, 2006.

FÓRUM DE DEBATES TRILHOS DO RIO. Passado, presente e futuro: tudo na mesma linha. Available at: https://www.trilhosdorio.com.br/forum/viewtopic.php?f=85&t=113. Accessed on: june 2025.

KÜHL, Beatriz Mugayar. Patrimônio industrial: algumas questões em aberto. arq.Urb, v. 3, p. 23-30, 2010. Available at: https://revistaarqurb.com.br/arqurb/article/view/115

LABASSE, Jean. L’organisation de l’espace: éléments de géographie voluntaire. Paris: Hermann, 1966.

LENCIONI, Sandra. Reestruturação urbano-industrial no Estado de São Paulo: a região da metrópole desconcentrada. In SANTOS, Milton; SOUZA, Maria Adélia; SILVEIRA, Maria Laura (Orgs.). Território : globalização e fragmentação. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1994.

LIMA, Rachel Gomes de. Ciranda da Terra: A dinâmica Agrária e seus conflitos. Dissertation (Master’s). Niterói: UFF, 2012.

LUZ, Nícea Vilela. A luta pela industrialização do Brasil. São Paulo, Editora Alfa-Ômega, 1978.

MARTINS, Ronaldo Luiz. Estação de Irajá arraial da encruzilhada [livro eletrônico] : 1600-2000. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. do Autor, 2023.

MELLO, João Manuel Cardoso de. O capitalismo tardio. São Paulo: Ed. Brasiliense, 1982

MENDONÇA, Sônia Regina de. As bases do desenvolvimento capitalista dependente: da industrialização restringida à internacionalização.In: LINHARES, Yedda Leite Linhares (Org.). História geral do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Elsevier, 1990.

MENEGUELLO, Cristina. Espaços e vazios urbanos. In: FORTUNA, Carlos; LEITE, Rogério Proença. (Orgs.). Plural de cidade: novos léxicos urbanos. Coimbra: Almedina, 2009. v. 1, p. 89-96.

MONTEIRO, Mônica dos Santos. Reocupação de vazios urbanos como estratégia para cidades (mais) sustentáveis: um olhar sobre a Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. (Master’s Dissertation). Fundação Getulio Vargas. Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. São Paulo, 2020.

MONTEIRO NETO, Aristides (Organizador); SILVA, Raphael de Oliveira; SEVERIAN, Danilo. Brasil, Brasis : reconfigurações territoriais da indústria no século XXI. IPEA, [s. l.], 2021.

OLIVEIRA, Márcio Pinon de. O padrão de localização da indústria têxtil no Brasil e no Rio de Janeiro, em fins do século XIX. Terra Livre , v. 1, p. 135-150, 2008.

PRADILLA COBOS, Emilio. Cambios neoliberales, contradicciones y futuro incierto de las metrópolis latinoamericanas. Cadernos Metrópole, São Paulo, v. 20, n. 43, p. 649-672, 2018.

RAMONET, Ignácio. Geopolítica do Caos. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1998.

REVEL, Jacques (Org.). Jogos de Escalas. A Experiência da Microanálise. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 1996.

RIBEIRO, Ana Clara Torres (Org.). Repensando a experiência urbana da América Latina: questões, conceitos, valores. Buenos Aires, Clacso, 2000.

RIBEIRO, Luiz Cesar de Queiroz (Org.). Globalização, fragmentação e reforma urbana: o futuro das cidades brasileiras na crise. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1994.

RIBEIRO, Marcelo Gomes. Desindustrialização nas Metrópoles Brasileiras. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Urbanos e Regionais, v. 26, e202403pt, 2024. Available at: https://rbeur.anpur.org.br/rbeur/article/view/7486/5582. Accessed on: junho de 2025.

RUFINONI, Manoela Rossinetti. Patrimônio Industrial. In: CARVALHO, Aline; MENEGUELLO, Cristina. (Orgs.) Dicionário temático de patrimônio: debates contemporâneos. Campinas: Editora UNICAMP, 2020. Cap. 29, p. 233-236.

SAMPAIO, Andrea. Vazios urbanos e Patrimônio Industrial: interfaces com o ordenamento urbanístico e o patrimônio cultural. In: BORDE, Andréa de Lacerda Pessoa. Vazios urbanos: percursos contemporâneos. Rio de Janeiro: RioBooks, 2012.

SANTOS, Joaquim Justino Moura dos. Contribuição ao Estudo da História do Subúrbio de Inhaúma de 1743 a 1920. Dissertation (Master’s in History). Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ, 1987.

SANTOS, Milton. Espaço e Sociedade. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes, 1982.

SANTOS, Milton. A Natureza do Espaço: Técnica e Tempo, Razão e Emoção. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 2012 .

SANTOS, Milton. A Urbanização Brasileira. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1993.

SASSEN, Saskia. As Cidades na Economia Mundial. São Paulo, Nobel, 1998.

SEVERINI, Valéria Ferraz. Políticas Públicas e a Transformação de Antigas Áreas Industriais – o caso da cidade de São Paulo. Revista Projetar, v.4, n.1, p. 8-23, abril de 2019.

SILVA, Heitor Nei Matias da. As ruínas da cidade industrial: resistência e apropriação social do lugar. Dissertation (Master’s). Rio de Janeiro, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Planejamento Urbano e Regional - IPPUR/UFRJ, 2008.

SILVA, Maria Laís Pereira da. Favelas cariocas: 1930-1964. Rio de Janeiro, Contraponto, 2005.

SIMONE, A. Surrounds: urban life within and beyond capture. Durham, NC, Duke University Press, 2022.

SLATER, David. Latin America and the Challenge to Imperial Reason: A Commentary on Arturo Escobar’s Paper. Cultural Studies, v. 25, n. 3, 2011, p. 450-458.

SOJA, Edward. Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 2000.

SOLIMANO, Andrès. Economic Growth under Alternative Development Strategies: Latin America from the 1940s to the 1990s. In CORICELLI, Fabrizio; MATEO, Massimo di; HAHN. New Theories in Growth and Development. Palgrave Macmillan, 1998. p. 270-291.

SOUZA, Leandro Gomes. Análise Espacial e Gestão Municipal de Vazios Urbanos no Rio de Janeiro. Dissertation (Master’s in Urban and Regional Planning). Rio de Janeiro, IPPUR/UFRJ, 2014.

SUZIGAN, Wilson. Estado e industrialização no Brasil. Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, [s. l.], v. 8, p. 493–504, 2024.

TAVARES, Hermes Magalhães. "Reestruturação econômica e as novas funções dos espaços metropolitanos". In: RIBEIRO, Ana Clara Torres (Org.). Repensando a Experiência Urbana da América Latina: Questões, Conceitos e Valores. Buenos Aires, Clacso, 2000. p. 89-104.

ZUKIN, Sharon. Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change. Newark: Rutgers University Press, 1989.

About the Authors

Maria Paula Albernaz is an architect (FAU/UFRJ), MSc in Urban Planning (PUR/UFRJ), PhD in Geography (PPGG/IGEO/UFRJ), and Postdoctoral researcher in Architecture (University of Sheffield, United Kingdom). She is a permanent faculty member of the Graduate Program in Urbanism (PROURB/FAU/UFRJ), associate professor at FAU/UFRJ, and co-coordinator of the Urban Projects Laboratory (LAPU/PROURB/UFRJ). Currently, she is the Vice-Coordinator of PROURB/FAU/UFRJ. Areas of expertise: urban production and transformation processes; urban planning practices; collaborative methods; industrial remnants; suburbs.

Carolina Maia Contarato is a Master’s student in Urbanism at the Graduate Program in Urbanism of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (PROURB-UFRJ) and a researcher at the Urban Projects Laboratory (LAPU). She holds a degree in Architecture and Urbanism from FAU-UFRJ (2022), with an exchange program at the Escola Tècnica Superior d’Arquitectura de Barcelona, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (2019–2020). Her research focuses on industrial remnants, metropolization, and the relationship between urbanization and environmental justice.

Marina Guerra Diógenes is an architect and urban planner (UFC), with one year of a sandwich scholarship from Science Without Borders (CsF) studying Development and Protection of Heritage and Cultural Landscapes at Université Jean Monnet de Saint-Étienne (France). MSc in Urbanism (PROURB/FAU/UFRJ), with a dissertation on the phenomenon of gentrification from a decolonial perspective, and PhD candidate (PROURB/FAU/UFRJ), researching housing policy and urban production, with a sandwich period at EHESS-Paris. She has been a member of the Urban Projects and City Laboratory (LAPU/PROURB/UFRJ) since 2020.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the following colleagues: Alexandra Lopes Monteiro, Amanda Lacerda Reis, Anna Jade Antunes dos Santos, Guilherme Brum Ferioli, Letícia Rangel, Marcella dos Santos Queiroz Pereira e Vitória Leão.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.A.; methodology, M.P.A., C.M.C., M.G.D.; formal analysis, M.P.A., C.M.C., M.G.D.; investigation, M.P.A., C.M.C., M.G.D.; data curation, M.P.A., C.M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.A.; writing—review and editing, M.P.A., C.M.C., M.G.D.; supervision, M.P.A.; project administration, M.P.A.; funding acquisition, M.P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CAPES, CNPq, FAPERJ, and UFRJ.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

About Coleção Estudos Cariocas

Coleção Estudos Cariocas (ISSN 1984-7203) is a publication dedicated to studies and research on the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, affiliated with the Pereira Passos Institute (IPP) of the Rio de Janeiro City Hall.

Its objective is to disseminate technical and scientific production on topics related to the city of Rio de Janeiro, as well as its metropolitan connections and its role in regional, national, and international contexts. The collection is open to all researchers (whether municipal employees or not) and covers a wide range of fields — provided they partially or fully address the spatial scope of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Articles must also align with the Institute’s objectives, which are:

- to promote and coordinate public intervention in the city’s urban space;

- to provide and integrate the activities of the city’s geographic, cartographic, monographic, and statistical information systems;

- to support the establishment of basic guidelines for the city’s socioeconomic development.

Special emphasis will be given to the articulation of the articles with the city's economic development proposal. Thus, it is expected that the multidisciplinary articles submitted to the journal will address the urban development needs of Rio de Janeiro.

[1] The central areas refer to the districts of Candelária, Santa Rita, Sacramento, Santo Antônio, São José, Gamboa, and Espírito Santo. The railway suburbs of the North Zone refer to the districts of Engenho Novo, Meyer, Inhaúma, and Irajá. AGACHE, Alfred. Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Extensão - Remodelação - Embellezamento. Paris: Prefeitura do Districto Federal/ Foyer Brésilien Editor, 1930. p.108. Available at: https://archive.org/details/cidadedoriodejan00alfr/page/106/mode/2up. Accessed in: June 2025.

[2] Source: Engenho de Dentro Workshops of the EFCB. Available at: http://vfco.vfco.com.br/ferrovias/estrada.de.ferro.central.do.brasil/memoria-historica-1908/0145-oficinas-do-Engenho-de-Dentro.shtm. Accessed in: June 2025.

[3] See Map of the Federal District City of Rio de Janeiro organized by Olavo Freire. Scale 1:71,000. Paris: Lithogr. Aillaud, Alves & Cia, 1911. Available at: https://bdlb.bn.gov.br/acervo/handle/20.500.12156.3/270181?locale-attribute=en. Accessed in: June 2025.

[4] The censuses of 1906 and 1920 show the growth of many professions in which middle-class people were included, such as liberal professionals (from 3.1% to 5.6%), administration (from 3.2% to 7.3%), commerce (from 16.1% to 18.3%), and public force (from 4.2% to 5.2%). AGACHE, Alfred. City of Rio de Janeiro. Extension - Remodeling - Beautification. Paris: Prefeitura do Districto Federal/ Foyer Brésilien Editor, 1930. p.106. Available at: https://archive.org/details/cidadedoriodejan00alfr/page/106/mode/2up. Accessed in: June 2025.

[5] Censuses 1950 and 1970 (IBGE).

[7] Despite the ongoing process, between 1980 and 1998, 1,384,266 m² of construction areas were licensed for industrial use in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro, indicating the continuity of manufacturing activity in the city, even with progressive reduction until the 2000s. Data from the table Construction areas licensed, by type of construction use - 1980-1998, sourced from the Municipal Department of Urbanism. INSTITUTO MUNICIPAL DE URBANISMO PEREIRA PASSOS. (Rio de Janeiro, RJ). Statistical Yearbook of the City of Rio de Janeiro. 1998. Rio de Janeiro: IPP, 2000, p. 555.

[8] Data from the table of licensed buildings, by use and respective administrative regions, sourced from the Municipal Department of Urbanism. INSTITUTO MUNICIPAL DE URBANISMO PEREIRA PASSOS. (Rio de Janeiro, RJ). Statistical Yearbook of the City of Rio de Janeiro. 1998. Rio de Janeiro: IPP, 2000, p. 556.