Volume 13 Issue 2 *Corresponding author paulaalbernaz@fau.ufrj.br Submitted 30 jun 2025 Accepted 28 july 2025 Published 08 aug 2025 Citation ALBERNAZ, M. P.; ALVES, M. L.; DIÓGENES, M. G. Refunctionalization of industrial remnants in the railway suburbs of the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro: obstacles and opportunities for reindustrialization. Coleção Estudos Cariocas, v. 13, n. 2, 2025.

DOI: 10.71256/19847203.13.2.152.2025 The article was originally submitted in PORTUGUESE. Translations into other languages were reviewed and validated by the authors and the editorial team. Nevertheless, for the most accurate representation of the subject matter, readers are encouraged to consult the article in its original language.

| Refunctionalization of industrial remnants in the railway suburbs of the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro: obstacles and opportunities for reindustrialization Refuncionalização de remanescentes industriais nos subúrbios ferroviários da Zona Norte do Rio de Janeiro: obstáculos e oportunidades para reindustrialização Refuncionalización de remanentes industriales en los suburbios ferroviarios de la Zona Norte de Río de Janeiro: obstáculos y oportunidades para la reindustrialización Maria Paula Albernaz1, Marina Louzada Alves2 e Marina Guerra Diógenes3 1PROURB/FAU-UFRJ, Av. Reitor Pedro Calmon, 550 – Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro – RJ, 21941-596, ORCID 0000-0002-1975-8490, paulaalbernaz@fau.ufrj.br 2PROURB/FAU-UFRJ, Av. Reitor Pedro Calmon, 550 – Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro – RJ, 21941-596, ORCID 0000-0002-5995-7744, marina.alves@fau.ufrj.br 3PROURB/FAU-UFRJ, Av. Reitor Pedro Calmon, 550 – Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro – RJ, 21941-596, ORCID 0000-0002-9669-7214, marina.diogenes@fau.ufrj.br

AbstractThis article explores the opportunities for reusing old, defunct factory structures, especially for reindustrialization, recognizing their potential for socioeconomic and territorial dynamism when reconfigured. The research focuses on the industrial remnants of the railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro's North Zone, prioritized in pioneering national industrialization initiatives, focusing on the analysis of their environmental, land, and fiscal conditions. The conclusion is that normative, institutional, and informational gaps in urban and environmental regulations must be filled by strengthening public policies aimed at offsetting the burdens likely to have arisen from the presence of these factories.

Keywords: Industrial remnants, North Zone of Rio de Janeiro, Reindustrialization. ResumoEste artigo visa refletir sobre as oportunidades do reaproveitamento de antigas estruturas fabris desfuncionalizadas especialmente para a reindustrialização reconhecendo seu potencial na dinamização socioeconômica e territorial quando reconfiguradas. O foco na pesquisa são os remanescentes industriais dos subúrbios ferroviários da Zona Norte do Rio de Janeiro, priorizados nas iniciativas pioneiras da industrialização nacional, centrando-se na análise centra-se das condições ambientais, fundiárias e fiscais apresentadas. Conclui-se pela exigência de se preencher lacunas normativas, institucionais e informacionais na regulamentação urbanística e ambiental com o fortalecimento de políticas públicas direcionadas a compensar ônus suscetíveis de ter ocorrido com a presença das fábricas.

Palavras-chave: Remanescentes industriais, Zona Norte do Rio de Janeiro, Reindustrialização. ResumenEste artículo explora las oportunidades de reutilizar estructuras fabriles antiguas y en desuso, especialmente para la reindustrialización, reconociendo su potencial de dinamismo socioeconómico y territorial al reconfigurarse. La investigación se centra en los remanentes industriales de los suburbios ferroviarios de la Zona Norte de Río de Janeiro, priorizados en iniciativas pioneras de industrialización nacional, y se centra en el análisis de sus condiciones ambientales, territoriales y fiscales. La conclusión es que las brechas normativas, institucionales e informativas en la regulación urbana y ambiental deben subsanarse mediante el fortalecimiento de las políticas públicas destinadas a compensar las cargas que probablemente hayan derivado de la presencia de estas fábricas. Palabras clave: Remanentes industriales, Zona Norte de Río de Janeiro, Reindustrialización. |

Introduction

The metropolises of Latin America, which during the period of national developmentalism between the 1930s and 1980s prioritized industrialization in their economies, are now left with an industrial legacy largely devoid of its original manufacturing function. The conflicts and opportunities brought about by this legacy open space for a discussion that remains underexplored. In this sense, this article aims to reflect on the opportunities presented by the reuse of obsolete industrial structures, particularly in light of reindustrialization, recognizing their potential to enhance socioeconomic and territorial dynamics when reconfigured.

The emptying of industrial, port, and railway areas, also experienced in core countries, forms the basis of a global debate that began in the mid-1960s. The focus of this debate is to seek solutions for abandoned or decaying warehouses and factories that have scarred and taken over large portions of cities in countries such as: the United States (Rust Belt: Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Detroit), the United Kingdom (Manchester, Sheffield, Glasgow), Germany (Ruhr Valley: Essen, Duisburg), and France (Roubaix, Saint-Étienne) (Alves, 2024; Rezende, 2025).

To address functional abandonment and, especially, industrial ruins, specific nomenclatures were created: in France, obsolete post-industrial spaces became known as “friches industrielles”; in the United Kingdom, “derelict land”; in Spanish-speaking countries, “ruinas industriales” or “baldíos industriales”; and in the United States, “brownfield sites”, a term encompassing not only former industrial facilities but also abandoned mines, landfills, railways, ports, airports, dams, and power plants (Mendonça, 2001; Meneguello, 2008, 2009). In the field of urbanism and urban planning, debates have most frequently centered on industrial heritage (Choay, 2003), motivating over time not only numerous scholarly works but also the development of international institutional documents, heritage charters, focused on the conservation and refunctionalization of this legacy, such as the Nizhny Tagil Charter of 2003 and the Dublin Principles of 2011 (Rufinoni, 2020).

Beyond the academic and heritage discussions involving the treatment of industrial legacy, Global North countries have advanced in formulating public policies and consolidating a specific legal framework aimed at the refunctionalization of such spaces. These initiatives have produced concrete and significant impacts in transforming former industrial areas. A central focus of these policies, alongside concerns with other environmental issues linked to these territories, was the systematic identification and remediation of contaminated areas, frequently found in old industrial sites and recognized as one of the main obstacles to their urban reintegration (Moraes et al., 2024).

In the Global South, more specifically in Brazil, the debate around the refunctionalization of industrial remnants is much more recent and initially followed the central countries’ trend of focusing on industrial heritage (Carvalho, Gagliardi, Marins, 2025; Kuhl, 2010; Rufinoni, 2020). Within this framework, there has been less attention given to the potential of spaces emptied of manufacturing function, to the historical processes involved, and to the role they could play in urban transformation dynamics. This article is directed at that discussion, aiming to evaluate how specific issues of the Brazilian context intersect with more universal aspects of the subject.

The most significant remnants of industrial legacy are currently found in the railway suburbs of Brazil’s two largest metropolises, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, as a result of the priority given to these major cities during the industrialization period, from the 1920s to the late 1970s.

In Rio de Janeiro, the railway suburbs of the northern zone, also identified with much of Planning Area 3, coincide with urban portions that were prioritized early on by national developmentalist policies due to their locational advantages. These parts of the city today share the investments in urban and road infrastructure once made to stimulate industrial development, as well as the effects of rapid urbanization and population growth, and the environmental, urban, and social consequences resulting from the decline of the manufacturing function.

The understanding of the current dynamics of the industrial sector and of the legacy of industries installed in the railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro’s northern zone has been shaped by information generated in exploratory research on industrial remnants in this area. Mapping operational, repurposed, or deactivated industrial establishments has allowed for an understanding of the relationship between broader logics and the local context with its legacy. This article aims to highlight the former industrial spaces now lying idle, often rendered invisible, that frequently exhibit signs of abandonment and are at the heart of territorial disputes. Beyond these attributes, the proposal is to emphasize the expectations their refunctionalization holds due to the singularities of the spatiotemporal accumulation of which they are repositories (Santos, 2012).

The proposal is to broaden the perspective, focusing on the possibility of reintegrating these idle post-industrial spaces through socially coherent uses relative to their local contexts. The motivation stems from the recognition that these territories, although marked by devaluation processes, carry significant potential for reappropriation, either through public policies or local initiatives, which, in one way or another, can benefit those who inhabit them (Santos, 1982). This stems from an initial reflection on industrial remnants that allows for envisioning urban futures that are inclusive, environmentally responsible, and responsive to the demands of peripheral populations.

In this sense, the intention is to reveal and provide guidelines for future projects and policies of refunctionalization that address the needs of suburbs as complex territories. This is justified by the scarcity of scientific material in the field of urbanism that covers different conditions related to industrial remnants, and by the need to develop tools that support the collection and detailing of information related to socio-environmental, legal, and fiscal evidence or indicators in order to study the industrial legacy. This is approached through the exploratory research already conducted on idle post-industrial spaces in the railway suburbs of the northern zone.

It is considered that in order to advance in identifying the gaps found, it is necessary to face the challenges related to the search for information on land ownership, fiscal issues, and the management of environmental liabilities, factors that directly affect the possibilities for reappropriation, reintegration, and refunctionalization of these spaces. Understanding these conditions is essential to serve as a foundation for new proposals and integrated guidelines that combine environmental recovery, mitigation of environmental damage, socio-environmental justice, and innovation in urban practices.

Overview of Idle Industrial Spaces in the Northern Zone Suburbs of Rio de Janeiro

Unlike São Paulo, where the deindustrialization or industrial decentralization of recent decades has transformed former working-class districts of the city’s so-called first industrial ring into middle-class neighborhoods, in Rio de Janeiro, the process took on a different configuration. It is therefore significant that the debates surrounding the industrial legacy originating from the São Paulo context focus on preservation and urban memory, as they relate to the demolition of old factories and industrial warehouses and their replacement with residential towers and gated communities in neighborhoods such as Mooca, Brás, Lapa, Tatuapé, among others (Meneguello, Fontes, Silva, 2009).

In Rio de Janeiro, however, most former industrial sites are located in a historically devalued region, until recently considered of little interest to the real estate market: the northern railway zone. This region, throughout the entire industrialization period, underwent a process of stigmatization and consequent real estate devaluation (Fernandes, 2011), a condition further aggravated by the emergence and growth of favelas as a consequence of industrialization.

Even so, in the railway suburb, the change of land use from industrial to residential and commercial is a recurring dynamic, intensified in the 21st century through municipal incentives via urban planning legislation aimed at the occupation of areas considered well-equipped with infrastructure yet underpopulated, such as Planning Area 3 (AP3), which in the 2001 Master Plan was categorized as a Macrozone of Incentivized Occupation (Rio de Janeiro, 2011). The analysis of industrial remnants in Rio de Janeiro’s northern railway zone reveals the significance of the recent trend of converting old industrial facilities into gated residential communities (Alves, 2024), raising the question of whether this is the most appropriate way to refunctionalize former industries with the aim of generating benefits for the city and especially for suburban residents.

The conversion of industrial remnants into gated residential communities, occupying former industrial plots generally larger than 15,000 square meters, mostly occurred in suburbs that have recently undergone urban interventions. Although these developments were included in the Minha Casa Minha Vida program, they targeted the middle-income population, reinforcing an already existing internal socio-spatial differentiation in the suburban region.

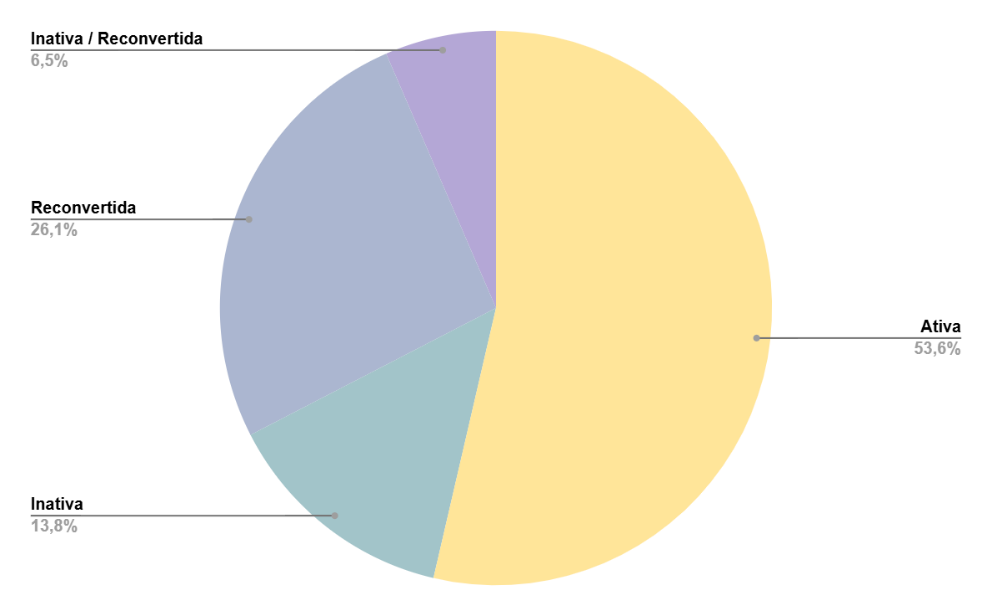

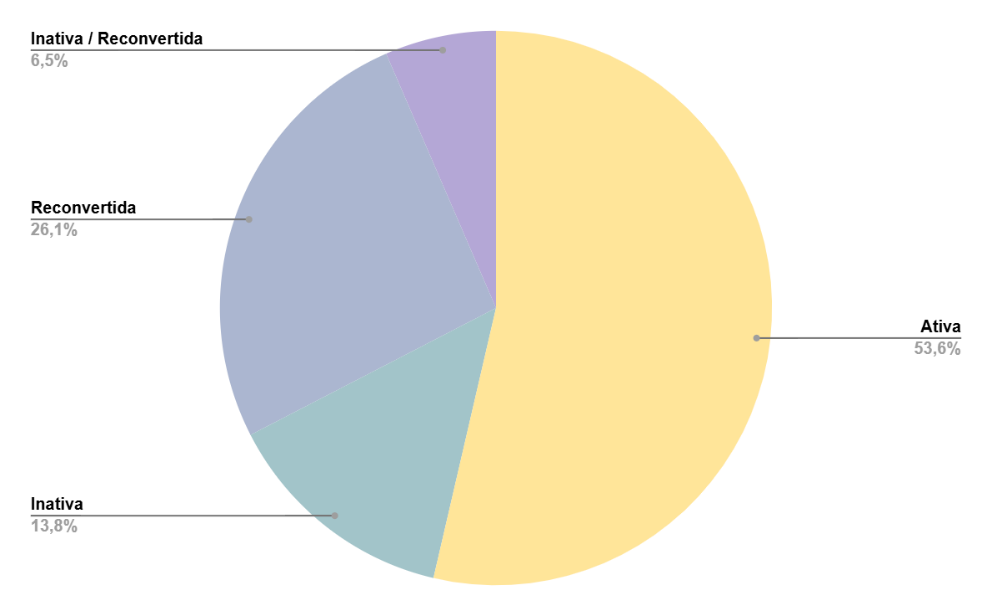

Based on recent exploratory research of approximately 250 mapped cases, industrial remnants can be categorized into four functional groups (see Figure 1): active industries, repurposed industries, inactive industries, and a hybrid category of inactive/repurposed. The first category refers to industries that remain operational and maintain their manufacturing function, accounting for about 53.6% of all identified cases in the region. The second category includes repurposed remnants that have undergone a refunctionalization process, whether or not preserving their industrial structures, representing 26.1% of the total. The third category includes inactive industries, currently idle and awaiting refunctionalization, which constitute 13.8%. A few cases fall into a hybrid state, considered a fourth category, where a single industrial site was subdivided, allowing part of the remnant to remain idle and part to be repurposed (6.5%).

Figure 1: Categories of industrial remnants in the northern railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro.

Source: Authors’ survey.

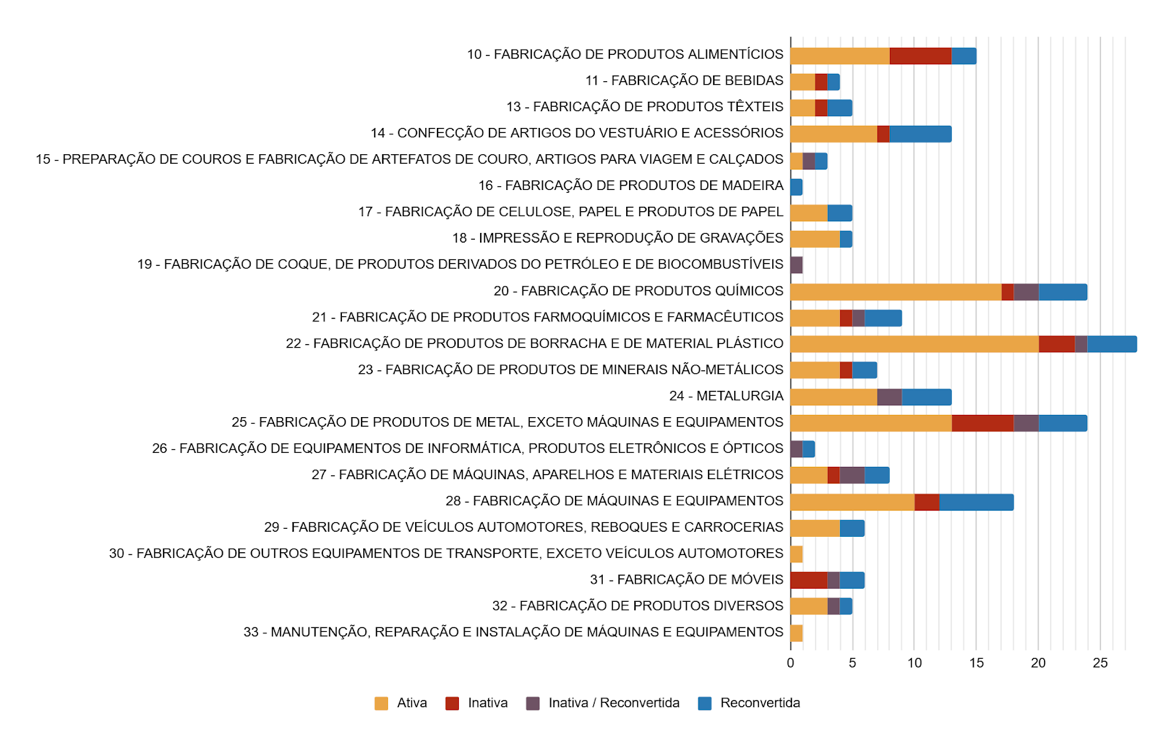

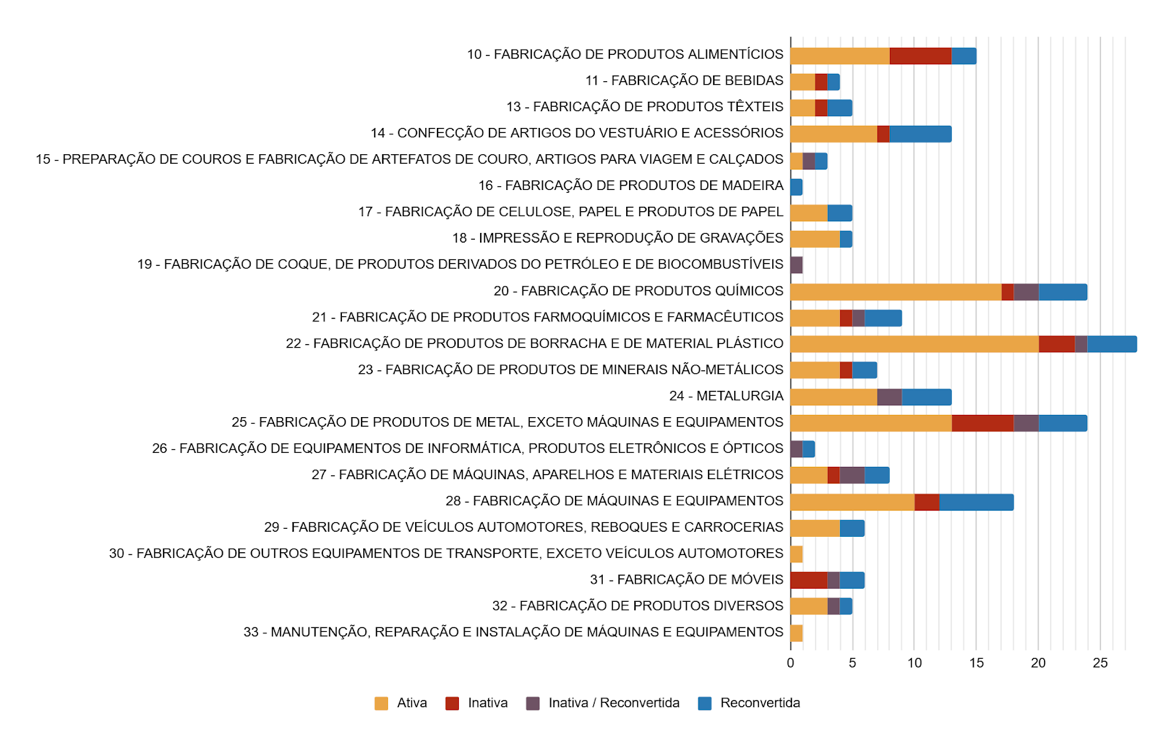

What stands out in the data presented in Figure 1 is the notable share of active industries among the industrial remnants. This percentage reveals that the industrial sector still plays a relevant role among the economic activities carried out in the northern zone suburbs of Rio de Janeiro, despite the decommissioning processes that have occurred, particularly since the late 1980s. Regarding the nature of the production in these active industries, some branches of the manufacturing industry have greater or lesser representation in the suburban region. Among the most prominent are the manufacture of rubber and plastic products, followed by the manufacture of chemical products, and then the manufacture of metal products, excluding machinery and equipment (see Figure 2). Certain industrial sectors, which never had a strong presence to begin with, have now been eliminated from production in the northern railway suburbs, such as the manufacture of wood products, petroleum and biofuels, and electronics.

Figure 2: Industrial remnants in the northern railway suburbs of Rio by analysis category and manufacturing industry activity.

Source: Authors’ survey.

Focusing on idle industrial remnants, the central subject of this article, classified as inactive industries, these represent nearly 15% of the total identified. Some specific aspects of the inactive industries concern the size of the lots or plots they occupy, as well as the immediate and local suburban context in which they are located. In terms of size, the majority of inactive industrial establishments, in absolute numbers, are small-scale facilities occupying areas up to 5,000 m² (around 65% of all inactive industries). However, it is also important to consider the actual area occupied by idle industries, which generally has a far greater urban, social, and environmental impact. There are at least two enormous inactive industrial remnants in the northern railway suburbs: the General Electric factory in Maria da Graça, with more than 200,000 m², and Vulcan Material Plástico LTDA in Colégio, with over 120,000 m², as well as others that occupy areas of more than 20,000 m², such as Estamparia Real in Coelho Neto, or more than 10,000 m², such as Tigre Ferramentas Construção Civil in Pavuna.

It is also worth noting that a significant number of the mapped industrial remnants, about 15, are characterized as being partially inactive and partially repurposed. These are commonly former large-scale facilities, such as Cimento Portland in Irajá, which occupied more than 130,000 m² and was partially converted into gated residential communities; Curtume Carioca in Penha, which covered almost 100,000 m², partially repurposed for gated residential communities and other uses; and Standard Electric in Vicente de Carvalho, with nearly 60,000 m², part of which was converted into the Shopping Carioca.

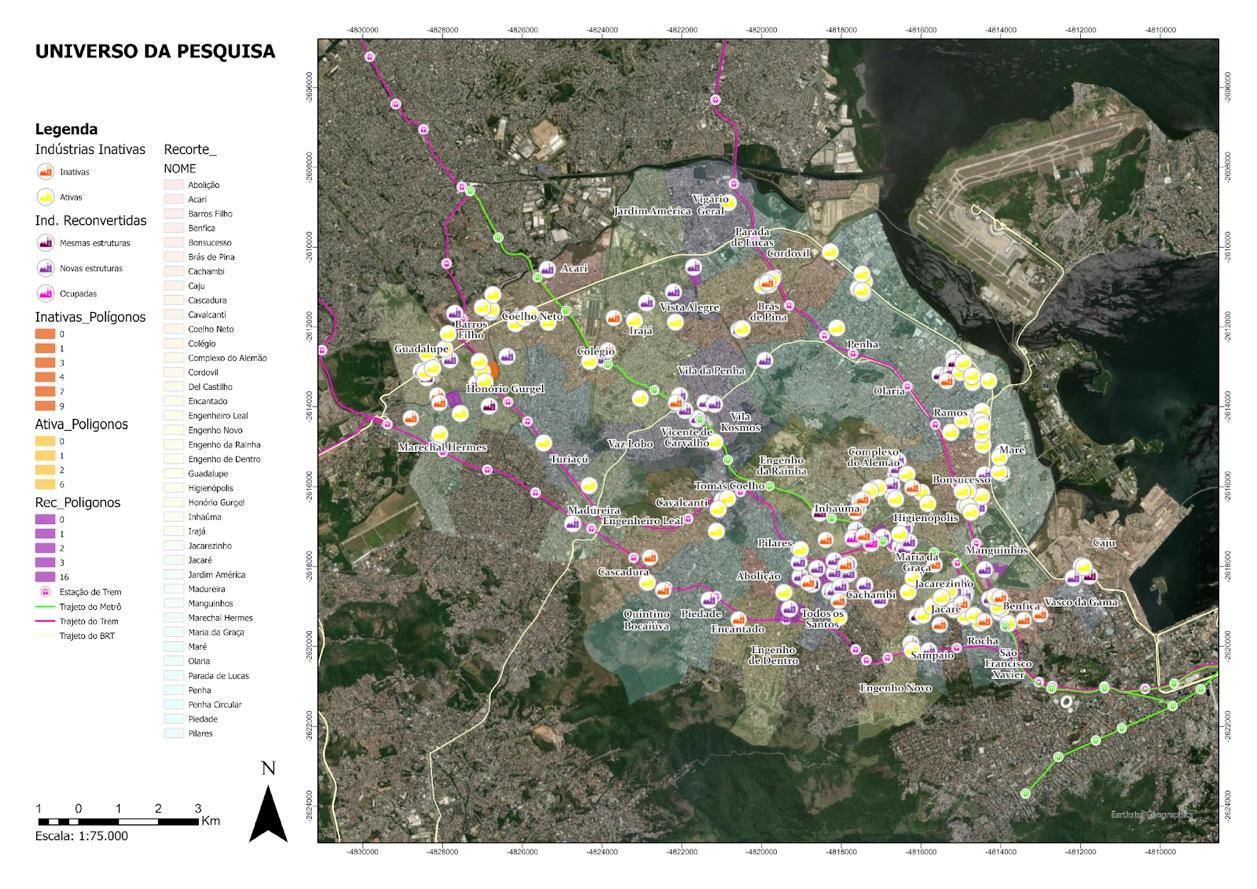

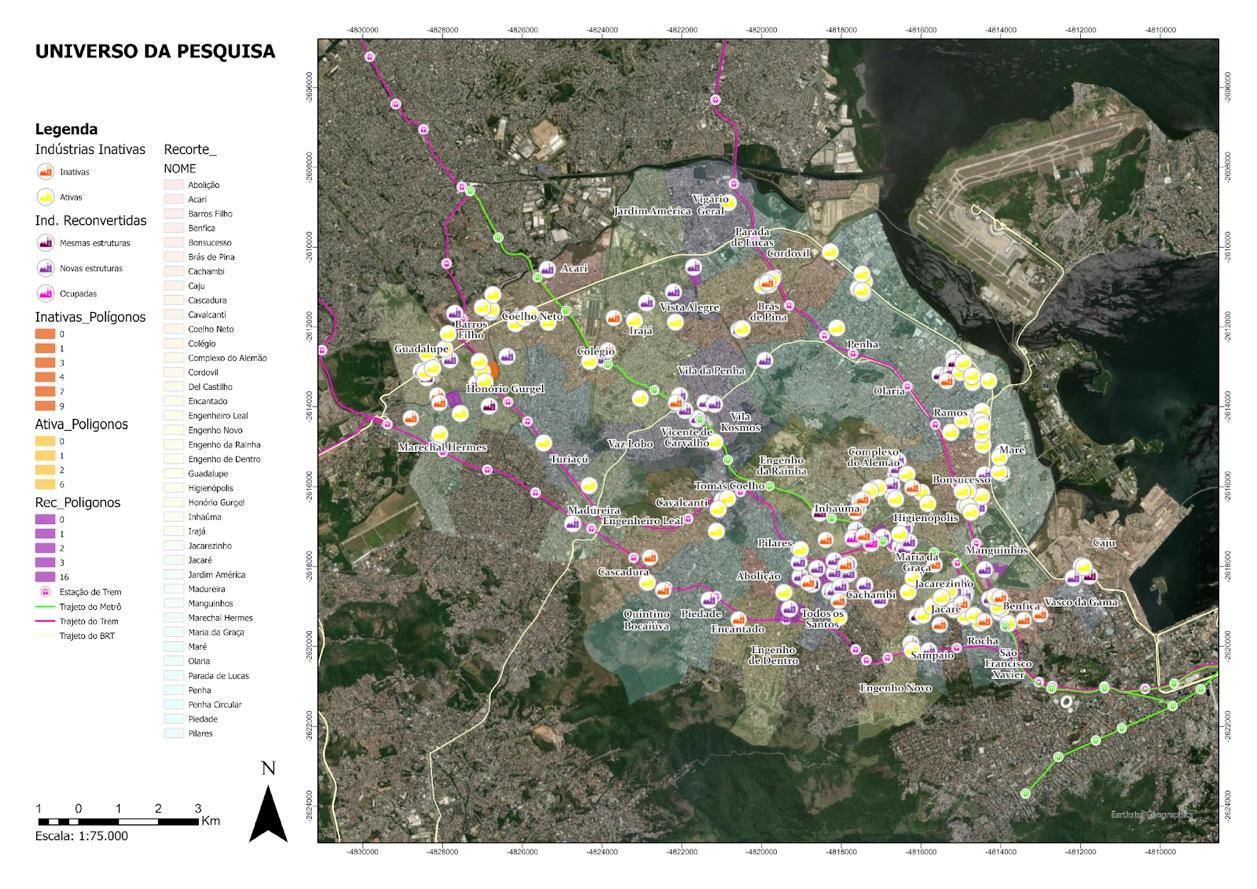

Regarding the location of industrial remnants by analysis category, active industries are spread throughout the suburban territory of the northern zone, with concentrations along Sacramento Street and in the neighborhoods of Bonsucesso, Ramos, Jacaré, and Maria da Graça. Repurposed industries are preferably located in higher-valued neighborhoods, clustering around the areas of Pilares, Cachambi, Todos os Santos; Vicente de Carvalho, Vila Cosmos, and Vila da Penha; and Vista Alegre and Irajá. Inactive industries are scattered throughout the northern railway suburbs, with concentrations in Benfica, Jacaré, Maria da Graça; Alemão Complex, Inhaúma; Cachambi, Todos os Santos; and Honório Gurgel (see Figure 3). With the exception of Cachambi and Todos os Santos, the remaining areas where inactive industries are located are characterized by their proximity to numerous favelas or even large favela complexes.

Figure 3: Map of industrial remnants in the northern railway suburbs by analysis category.

Source: Authors (2025).

Institutional and Environmental Gaps in Idle Industrial Spaces in Rio de Janeiro

As in many other countries, industrialization, combined with urban expansion, has caused severe environmental and landscape impacts across several areas. These impacts have often been, and still are, systematically neglected by institutional oversight bodies or by political decisions driven by various interests. In this context, it is important to revisit the legal and institutional framework that guides environmental protection in the country to understand where the normative and institutional gaps lie that give rise to this situation.

According to the 1988 Federal Constitution, under items III, VI, and VII of the caput and sole paragraph of Article 23 (Brasil, 1988), cooperation among the Union, States, Federal District, and Municipalities is assured in administrative actions aimed at environmental protection. This cooperation includes the preservation of documents, works, and other assets of historical, artistic, and cultural value, as well as notable natural landscapes and archaeological sites. It also encompasses environmental protection, the fight against all forms of pollution, and the preservation of forests, fauna, and flora.

In Brazil, Environmental Law emerged during the 1980s, particularly through Law 6.938 of 1981, considered the National Environmental Policy (PNMA), inspired by the U.S. National Environmental Policy Act of 1970. This law marked an initial advancement in the design of Brazilian legal control mechanisms, such as environmental licensing, and environmental impact studies (EIA/RIMA), among others.

Still within the Brazilian legal framework and the premises of Environmental Law, degradation arises, among other causes, from industrial processes within the urban perimeter throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, mainly in São Paulo, and to a lesser extent in Rio de Janeiro, such as in the northern suburban area and around the road axis of Sacramento Street. For much of its existence, this degradation occurred during the so-called “unregulated exploitation” phase, a historical process marked by the complete legislative omission regarding resource exploitation and the control of production processes capable of harming the environment.

Despite the advancement of environmental legislation and the existence of deliberative councils such as the National Environmental Council (CONAMA) and its local bodies, such as the State Environmental Council of Rio de Janeiro (CONEMA-RJ), many cases of environmental liabilities still persist without proper mitigation measures. Added to this is the weakness of municipal regulations regarding land use and occupation in contaminated or environmentally sensitive areas. CONAMA Resolution No. 420/2009, for example, sets guidelines for the characterization and rehabilitation of contaminated areas, as well as guidelines for environmental management. However, its effectiveness depends heavily on coordinated action among federal entities and the strength of local political will.

Concerning public health, since 2004, greater attention has been paid to the exposure of people living in areas affected by or at risk of contamination from chemical substances. Support services have been expanded through Health Surveillance within the Unified Health System (SUS). An example is the Health Surveillance Information System for Populations Exposed to Contaminated Soil (SISSOLO), which aims to monitor these vulnerable communities based on continuous records maintained by state and municipal health departments. The National System of Toxic-Pharmacological Information (SINITOX), in turn, is responsible for organizing and coordinating the collection, analysis, and dissemination of data on poisoning and intoxication cases in Brazil. These reports are made through the National Network of Toxicological Information and Assistance Centers (Renaciat), which operates across several regions of the country.

The creation of public tools such as SISSOLO and SINITOX reflects institutional recognition of socio-environmental inequalities and the unequal health impacts on different bodies and territories. However, the technical-sanitary approach remains fragmented in many cases, failing to integrate urban and environmental aspects with issues related to individual health. Some larger-scale environmental issues are treated as isolated externalities, without accounting for the socio-economic and urban structures that perpetuate socio-environmental injustice. It is within this context that struggles for environmental justice[1] resurface and align with the need to mitigate the effects of pollution and environmental degradation stemming from the expropriation of environmental components viewed as mere resources (Benjamin, 2001).

In this light, environmental concerns in industrial areas must take precedence over, or be addressed simultaneously, with economic and urban issues. It is necessary to recognize that urbanization, industrialization, and economic development have been accompanied by a process of accumulating environmental harm. The view of society and nature as distinct and separate domains must be overcome. This separation leads to technical and depoliticized responses to problems that are deeply social and historical, and it overlooks the disproportionate allocation of environmental risks to the poorest and most racialized populations.

It is also important to note that when responses focus solely on climate impacts, such as floods, droughts, water crises, ecosystem degradation, deforestation, among others,there is a risk of naturalizing environmental damage and depoliticizing its causes. Frequently, the response comes in the form of technical solutions (resilience, adaptation, green infrastructure) that do not address the root causes of socio-spatial inequalities and are co-opted by global technocratic agendas, pursuing abstract goals that tend to depoliticize environmental conflict.

As seen in the previous section, former industrial sites are increasingly being repurposed for residential or commercial uses, characterizing a prevailing contemporary trend (Albernaz, 2025). Developers often treat former industrial lands as a tabula rasa, demolishing all built structures to make way for so-called “renewal” without much concern for the environmental liabilities left behind by the industrial establishments.

In line with the above, it is also important to highlight the institutional gap in recognizing the State’s presence in the ownership of many industrial remnants, whether due to its role as a producer of suburban land for public industrial investment or due to the fiscal conditions of certain industries. Cross-referencing the interest in the industrial legacy with an understanding of its local context and with data on land tenure and taxation could open new paths for public policy alternatives toward its refunctionalization.

The incentives provided by the national state for industrialization since 1930 were not limited, as some authors suggest (Luz, 1978; Mendonça, 1990), to infrastructure works that facilitated the establishment of industries. With the rise of the Estado Novo dictatorship in 1937, new forms of stimulus emerged, both through support and benefits for private investors and through direct public investment in the industrial sector (Mendonça, 1990). In this sense, the State’s role became not only more aggressive in driving the national industrialization process but also more influential in shaping land tenure conditions in the territories prioritized for its investments.

As a result, the ownership of many areas, some quite extensive, became public in the northern railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro during the city’s industrialization process. Exploratory research into industrial remnants has revealed the presence of areas occupied by the State, such as the Graphic Park of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), an industrial unit dedicated to printing maps, statistics, images, and census reports, located on an 85,500 m² plot in Parada de Lucas. It was also possible to identify the repurposing of industrial areas such as that of Embratel, a telecommunications industry in Manguinhos, which occupied an area of nearly 30,000 m² reclaimed from landfill in former mangrove areas near Guanabara Bay.

In the survey of active or idle industrial remnants, especially small-scale ones occupying up to 5,000 m², it was found that many are in the process of bankruptcy. Some larger remnants, exceeding 30,000 m², are also in this condition. It is essential to understand the fiscal status of these remnants and the regulations governing them to assess the potential for public policies aimed at their refunctionalization.

Final Considerations

The analysis of idle industrial remnants in the northern railway suburbs of Rio de Janeiro reveals a range of particularities that challenge both traditional approaches to refunctionalization and models imported from international experiences. Unlike processes observed in cities of the Global North, where the revaluation of former industrial complexes is often associated with heritage designation and urban revitalization in contexts of greater social and institutional capital, the suburban reality of Rio de Janeiro is marked by a complex intersection of historical devaluation, socio-environmental precariousness, and a lack of public interest and effective instruments. At the same time, the study reveals that these spaces can also be sites of contestation, of formal and informal appropriation, of social reinvention, and of innovative urban practices. The types of use identified in conversions reflect the range of interests at play and reinforce the need for a critical perspective, attentive to local dynamics and the concrete conditions of each territory.

Given the normative, institutional, and informational gaps surrounding this issue, it is urgent to build an approach that integrates land, environmental, social, and urban planning dimensions. This demands the strengthening of public policies guided by an intersectoral concern, involving coordination among agencies and departments responsible for different aspects of urban management. It also implies a commitment to criteria of socio-environmental justice, recognizing the specificities of peripheral territories, the value of the relationship between residents of the northern railway suburbs and the industrial world, and the need to compensate for environmental and social burdens that may have resulted from the presence of significant, numerous, and often polluting factories.

Thus, more than simply replicating models of refunctionalization, this study underscores the need to understand such areas as potential spaces for economic and territorial revitalization, especially when reconfigured in line with social demands and local specificities. One of the challenges lies in envisioning and structuring new institutional and technical arrangements that regard the industrial past as part of urban history and as a pathway for future interventions. Spaces that are now degraded and idle may, under a different logic, be reappropriated as sites of social transformation, with urban research serving as a critical tool for reimagining the city.

References

ALBERNAZ, Maria Paula. Remanescentes industriais suburbanos: potência transformadora do legado desenvolvimentista latino-americano. Cadernos Metrópole, [S. l.], v. 27, n. 62, p. e6266078, 2024. Available at: https://revistas.pucsp.br/index.php/metropole/article/view/66078. Accessed on: 29 jun. 2025.

ALVES, Marina Louzada. Reconversão de Remanescentes Industriais em Condomínios Verticalizados: a produção de um novo subúrbio ferroviário carioca. 2024. Dissertation (Master’s in Architecture) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Urbanismo, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

BENJAMIN, Antônio Herman de Vasconcellos. A natureza no direito brasileiro: coisa,sujeito ou nada disso. Caderno jurídico, Escola Superior do Ministério Público, no. 2, july, 2001.

BRASIL. Constitution (1988). Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil. Brasília, DF: Federal Senate, 1988. 292p.

CARVALHO, Mônica de; GAGLIARDI, Clarissa; MARINS, Paulo César Garcez. Patrimônio cultural e capital urbano: disputas em torno dos legados industriais (Editorial). Cadernos Metrópole, São Paulo, v. 27 n. 62, p. 1-14, 2025.

CAVALCANTI, Mariana; FONTES, Paulo. Ruínas industriais e memória em uma “favela fabril” carioca. História Oral, v. 14, n. 1, 2012.

CHOAY, Françoise. Alegoria do Patrimônio. Tradução de Pedro de Souza. São Paulo: UNESP, 2003.

CONAMA – National Environment Council. CONAMA Resolution no. 420, of December 28, 2009. Establishes criteria and guiding values for soil quality concerning the presence of chemical substances and provides guidelines for the environmental management of areas contaminated by such substances due to anthropic activities. Brasília, December 2009.

CRUVINEL, Aline Cristina Fortunato; RIBEIRO, Cláudio Rezende. Memória, trabalho e cidade: contribuições para o debate contemporâneo sobre o lugar da classe trabalhadora. Cantareira, 34ª ed. Jan-Jun, 2021.

FERNANDES, Nelson da Nóbrega. O rapto ideológico da categoria subúrbio: Rio de Janeiro 1858/1945. Rio de Janeiro: Apicuri, 2011, 176p.

GHIBAUDI, Javier Walter. A Nova Fábrica é o Bairro? O trabalho político e territorial de duas organizações de cooperativas na periferia de Buenos Aires. R.B. Estudos Urbanos e Regionais, v. 15, n.2, novembro de 2013.

HIGH, Steven; MACKINNON, Lachlan; PERCHARD, Andrew (org.). The deindustrialized world: confronting ruination in postindustrial places. Toronto: UBC Press, 2017. 388 p.

KÜHL, Beatriz Mugayar. Algumas questões relativas ao patrimônio industrial e à sua preservação. Patrimônio.Revista Eletrônica do IPHAN, n. 4, 2006. Tradução. Disponível em: http://www.revista.iphan.gov.br/materia.php?id=165. Accessed on: 30 june 2025.

LUZ, Nícea Vilela. A luta pela industrialização do Brasil. São Paulo, Editora Alfa-Ômega, 1978.

MENDONÇA, Adalton da Motta. Vazios e ruínas industriais. Ensaio sobre friches urbaines. Arquitextos, São Paulo, ano 02, n. 014.06, Vitruvius, jul. 2001. Available at: https://vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/arquitextos/02.014/869.

MENDONÇA, Sônia Regina de. As bases do desenvolvimento capitalista dependente: da industrialização restringida à internacionalização.In: LINHARES, Yedda Leite Linhares (Org.). História geral do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Elsevier, 1990.

MENEGUELLO, Cristina. Da ruína ao edifício: neogótico, reinterpretação e preservação do passado na Inglaterra vitoriana. São Paulo: Annablume, 2008. v. 1.

MENEGUELLO, Cristina. Espaços e vazios urbanos. In: FORTUNA, C.; LEITE, R. P. (Org.). Plural de cidade: novos léxicos urbanos. Coimbra: Almedina, 2009. v. 1, p. 89-96.

MENEGUELLO, Cristina; FONTES, Paulo; SILVA, Leonardo. Patrimônio industrial e especulação imobiliária: o caso da Lapa, São Paulo. Minha Cidade, São Paulo, ano 09, n. 107.04, Vitruvius, jun. 2009. Available at: https://vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/minhacidade/09.107/1847.

MORAES, Sandra Lúcia de; TEIXEIRA, Cláudia Echevenguá; MAXIMIANO, Alexandre Magno de Sousa (Org.). Guia de elaboração de planos de intervenção para gerenciamento de áreas contaminadas. 1. ed. rev. São Paulo: IPT - Instituto de Pesquisas Tecnológicas do Estado de São Paulo: BNDES, 2014.

REZENDE, Rafael. Patrimônio industrial, identidade e memória: o caso do Vale do Ruhr. Cadernos Metrópole, v. 27, n. 62, p. e6265884, 2025.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Município). Lei Complementar nº 229, de 14 de julho de 2021. Institui o Plano Diretor de Desenvolvimento Sustentável do Município do Rio de Janeiro. Available at: https://leismunicipais.com.br/plano-diretor-rio-de-janeiro-rj. Accessed on: 30 june 2025.

RUFINONI, Manoela Rossinetti. Patrimônio Industrial. In: CARVALHO, Aline; MENEGUELLO, Cristina. (Orgs.) Dicionário temático de patrimônio: debates contemporâneos. Campinas: Editora UNICAMP, 2020. Cap. 29, p. 233-236.

SANTOS, Milton. Espaço e Sociedade. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes, 1982.

SANTOS, Milton. A Natureza do Espaço: Técnica e Tempo, Razão e Emoção. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 2012.

SOBRAL, Bruno Leonardo. A evidência da estrutura produtiva oca: o estado do Rio de Janeiro como um dos epicentros da desindustrialização nacional. In: NETO, Aristides Monteiro; CASTRO, César Nunes (Orgs.). Desenvolvimento regional no Brasil: políticas, estratégias e perspectivas. Rio de Janeiro: IPEA, 2017.

TUNES, Regina. Helena. A perspectiva da geografia econômica sobre a dinâmica industrial do Rio de Janeiro. Revista GeoUECE, v. 9, n. 16, p. 81-96, 2020.

About the Authors

Maria Paula Albernaz is an architect (FAU/UFRJ), MSc in Urban Planning (PUR/UFRJ), PhD in Geography (PPGG/IGEO/UFRJ), and Postdoctoral researcher in Architecture (University of Sheffield, United Kingdom). She is a permanent faculty member of the Graduate Program in Urbanism (PROURB/FAU/UFRJ), associate professor at FAU/UFRJ, and co-coordinator of the Urban Projects Laboratory (LAPU/PROURB/UFRJ). Currently, she is the Vice-Coordinator of PROURB/FAU/UFRJ. Areas of expertise: urban production and transformation processes; urban planning practices; collaborative methods; industrial remnants; suburbs.

Marina Louzada Alves is an architect and urban planner (FAU/UFRJ), MSc in Urbanism (PROURB/FAU/UFRJ), with a thesis on the socio-spatial impacts of local deindustrialization in suburban areas of the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro, focusing on the conversion of industrial remnants into verticalized condominiums. She is currently a PhD student in Urbanism (PROURB/FAU/UFRJ).

Marina Guerra Diógenes is an architect and urban planner (UFC), with one year of a sandwich scholarship from Science Without Borders (CsF) studying Development and Protection of Heritage and Cultural Landscapes at Université Jean Monnet de Saint-Étienne (France). MSc in Urbanism (PROURB/FAU/UFRJ), with a dissertation on the phenomenon of gentrification from a decolonial perspective, and PhD candidate (PROURB/FAU/UFRJ), researching housing policy and urban production, with a sandwich period at EHESS-Paris. She has been a member of the Urban Projects and City Laboratory (LAPU/PROURB/UFRJ) since 2020.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Carolina Maia Contarato, Gabriele de Oliveira Pinto, Anna Jade Antunes dos Santos, Marcella dos Santos Queiroz Pereira, and Vitória Leão.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.A., M.L.A.; methodology, M.P.A., M.L.A., M.G.D.; investigation, M.P.A., M.L.A., M.G.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.A., M.L.A., M.G.D.; writing—review and editing, M.P.A., M.L.A., M.G.D.; supervision, M.P.A., M.L.A., M.G.D.; funding acquisition, M.P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CAPES, CNPq, FAPERJ, and UFRJ.

Data Availability

The data supporting this study are available on the project’s digital platform at: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/bd7ea50088574fcabfe60fbdd2a48b19

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

About Coleção Estudos Cariocas

Coleção Estudos Cariocas (ISSN 1984-7203) is a publication dedicated to studies and research on the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, affiliated with the Pereira Passos Institute (IPP) of the Rio de Janeiro City Hall.

Its objective is to disseminate technical and scientific production on topics related to the city of Rio de Janeiro, as well as its metropolitan connections and its role in regional, national, and international contexts. The collection is open to all researchers (whether municipal employees or not) and covers a wide range of fields — provided they partially or fully address the spatial scope of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Articles must also align with the Institute’s objectives, which are:

- to promote and coordinate public intervention in the city’s urban space;

- to provide and integrate the activities of the city’s geographic, cartographic, monographic, and statistical information systems;

- to support the establishment of basic guidelines for the city’s socioeconomic development.

Special emphasis will be given to the articulation of the articles with the city's economic development proposal. Thus, it is expected that the multidisciplinary articles submitted to the journal will address the urban development needs of Rio de Janeiro.

[1] The environmental justice movement in the United States began exploring the intersections between environmental degradation and the social conditions experienced by subordinate populations as early as 1982, examining issues of environmental racism and the marginalization of working-class African American neighborhoods in relation to pollution problems or environmental decline. (High; Mackinnon, Lachlan; Perchard, 2017, p. 81)