Volume 13 Issue 2 *Corresponding author vitorvboanova@gmail.com Submitted 14 july 2025 Accepted 06 sep 2025 Published 03 oct 2025 Citation BOA NOVA, V. V. F., JABBOUR, E. M. K. ‘‘Project Rio 2050’: projectment as a strategy for Rio de Janeiro’s economic and social development in the coming decades. Coleção Estudos Cariocas, v. 13, n. 2, 2025.

DOI: 10.71256/19847203.13.2.158.2025 The article was originally submitted in PORTUGUESE. Translations into other languages were reviewed and validated by the authors and the editorial team. Nevertheless, for the most accurate representation of the subject matter, readers are encouraged to consult the article in its original language.

| ‘Project Rio 2050’: projectment as a strategy for Rio de Janeiro’s economic and social development in the coming decades ‘Projeto Rio 2050’: o projetamento como estratégia de desenvolvimento econômico e social do Rio de Janeiro para as próximas décadas ‘Proyecto Río 2050’: el proyectamiento como estrategia para el desarrollo económico y social de Río de Janeiro en las próximas décadas Vitor Vieira Fonseca Boa Nova1 and Elias Marco Khalil Jabbour2 1Instituto Municipal de Urbanismo Pereira Passos, R. Gago Coutinho, 52 - Laranjeiras, Rio de Janeiro - RJ, 22221-070, ORCID 0000-0003-0496-7465, vitorvboanova@gmail.com 2Instituto Municipal de Urbanismo Pereira Passos and Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, R. Gago Coutinho, 52 - Laranjeiras, Rio de Janeiro - RJ, 22221-070, ORCID 0000-0003-0946-1519, emkjabbour@gmail.com

AbstractThis article proposes an economic and social development strategy for the city of Rio de Janeiro based on the concept of projectment, articulating the development of productive forces with the reduction of social and territorial inequalities. Starting from a diagnosis of the city's structural contradictions, it outlines “Projeto Rio 2050” as a key project that guides tasks, axes, guidelines, and derivative projects. The proposal seeks to reposition Rio as a dynamic center in the national development process, through a new wave of industrialization grounded in the implementation of urban and transport projects as a path toward a more just city. Keywords: development strategy, projectment, Rio de Janeiro ResumoO artigo propõe uma estratégia de desenvolvimento econômico e social para o Rio de Janeiro com base no conceito de projetamento, articulando o desenvolvimento das forças produtivas à redução das desigualdades sociais e territoriais. A partir de um diagnóstico das contradições estruturais da cidade, delineia o “Projeto Rio 2050” como projeto-chave orientador de tarefas, eixos, diretrizes e projetos derivados. A proposta busca reposicionar o Rio como núcleo dinâmico no processo nacional de desenvolvimento, a partir de um novo impulso de industrialização baseado na execução de projetos urbanos e de transporte como caminho para a promoção de uma cidade mais justa. Palavras-chave: estratégia de desenvolvimento, projetamento, Rio de Janeiro ResumenEl artículo propone una estrategia de desarrollo económico y social para la ciudad de Río de Janeiro basada en el concepto de proyectamiento, articulando el desarrollo de las fuerzas productivas con la reducción de las desigualdades sociales y territoriales. A partir de un diagnóstico de las contradicciones estructurales de la ciudad, se delinea el “Proyecto Río 2050” como proyecto clave que orienta tareas, ejes, directrices y proyectos derivados. La propuesta busca reposicionar a Río como un núcleo dinámico en el proceso de desarrollo nacional, a través de un nuevo impulso de industrialización sustentado en la ejecución de proyectos urbanos y de transporte como vía hacia una ciudad más justa. Palabras clave: estrategia de desarrollo, proyectamiento, Río de Janeiro

|

Introduction

Rio de Janeiro is possibly the Brazilian city that most intensely represents the country, a symbol of national identity and potential (Lessa, 2000). Be it in its positive aspects, such as the beautiful and stunning landscapes that uniquely integrate the urban and the natural, its cultural and historical wealth, its role as the capital of the Empire and the Republic for a large part of the nation's history, in addition to having been the setting for central political episodes; or in its negative aspects, such as urban violence and the actions of criminal organizations, the high levels of social and economic inequality, the process of deindustrialization and its consequences, unemployment and informality in the labor market, and the precariousness of infrastructure and access to urban goods and services, still insufficient to meet the population's demand and unevenly distributed across the territory.

It is as if Rio were a sort of urban synthesis of Brazil: many of its main problems mirror those of the country, and the most urgent challenges faced nationally are also manifested in its local reality. So much so that moving towards solving the city's structural problems is a fundamental part of confronting the major national challenges. If, on the one hand, the absence of a clear national development strategy may limit Rio de Janeiro's capacity to overcome its impasses, on the other hand, the construction of a national development project must necessarily involve a specific project for Rio. The latter could even function as a broadcaster of trends and a laboratory for advanced experiences for other cities and regions of the country.

In this context, given the profound economic, social, and territorial inequalities that mark the city of Rio de Janeiro and its regional-metropolitan surroundings, more than elaborating a critical analysis, this article aims to make the analytical exercise a starting point for proposing strategies to address its main problems and challenges. It starts, therefore, from a scientific conception that is not limited to interpreting reality, committing itself above all to the task of transforming it. This is why the focus, regarding theoretical frameworks, is on their use as an analytical-propositional tool, avoiding academic speculations that could deviate from the intended purpose here.

Thus, the aim is to reposition the city amidst the ongoing transformations in the contemporary world, from a perspective that recognizes the importance of Rio de Janeiro for the advancement of a national development project. Strategies that simultaneously articulate the development of productive forces, aiming to increase productivity and the capacity to generate wealth, and the universalization of access to employment and urban and social goods and services, with a view to reducing inequalities in their multiple dimensions and improving the quality of the urban environment, encompassing the environmental dimension and the relationship between society and nature, while the urban is an artificial environment.

To this end, the method involved an analysis of indicators, studies, and academic publications, as well as documents from municipal public entities, which contributed to the construction of a basic diagnosis of the city's current economic and social conditions and its main challenges. As a propositional exercise, based on this diagnosis, we sought to present a strategic conception of development, discussing its fundamental concepts and categories. Finally, we deepened the reflection on alternatives and proposals for political and institutional intervention, identifying tasks, axes, guidelines, and projects considered strategic for promoting the economic and social development of Rio de Janeiro in the coming decades.[1]

The development of productive forces as a precondition for addressing the urban and social inequalities of Rio de Janeiro

The first step in proposing the task of transforming reality is to seek to understand it, not only in its appearance, but above all in its essence, capturing the main contradictions and their respective aspects (Mao, 1999).

In order to present a brief diagnosis of the economic and social situation of Rio de Janeiro, it can be stated that the main contradiction in the development process of the city and its regions of influence currently lies in, on one hand, a growing and accumulated social demand for better living conditions, which involves access to jobs, infrastructure, facilities, and higher quality urban services, and, on the other hand, a difficulty in raising the level of local productive forces, especially in key sectors and activities, limiting the possibility of generating sufficient income, wealth, goods, and services to meet social demands.

If the city, as a national unit, lacks the conditions to create/produce or acquire/import the goods and services that provide material support for social rights and needs, then the principal aspect of this main contradiction lies in the urgency to develop its productive forces, quantitatively, granting greater capacity for accumulation and reproduction on an expanded scale (Marx, 2014), and qualitatively, through the formation of a productive supply structure that corresponds to the structure of socially determined demand.

This main contradiction objectively places the issue of industry and the reindustrialization of the city and the country as a whole at the center of the question, and, if we want to consider it from a historical perspective, it is necessary to take into account the process of deindustrialization that Rio and Brazil experienced from the 1990s onwards (Cano, 2008; Silva, 2012), albeit with developmentalist attempts in the first two Lula governments and the first Dilma government (Singer, 2015), interrupted during the Temer and Bolsonaro governments and now resumed in President Lula's third term.

Whereas the process of deindustrialization can be understood as the primary factor from which other forms and aspects that constitute the main contradiction already pointed out unfold. The fragility of industrial and productive activity in the city of Rio de Janeiro provokes both a situation of structural unemployment and a labor market, largely based on services geared towards precarious, informal, and low-wage occupations (Hasenclever et al., 2012), as well as a financial stranglehold, which incapacitates the State, at its municipal, state, and federal levels, from making sufficient investments in infrastructure projects, facilities, and urban services with the potential to reduce profound social and territorial inequalities by promoting greater equity among the various neighborhoods and areas of the city and in the living conditions of its population.

The economic emptying that Rio de Janeiro has been experiencing over the last five decades was, for example, the most intense among the country's main cities. If in 1970 Rio's GDP represented 12.8% of the national GDP, by 2016 its share had reduced to just 5.2%, suffering a negative variation of 59% during this period. Although this was a trend observed in capital cities in general[2], including São Paulo, which had a negative variation of 48.4% in its share of the national GDP in this same period, it was undoubtedly Rio de Janeiro that suffered the most (see Table 1).

Table 1: Variation in the relative participation of capitals between 1970 and 2016 in the National GDP

Capitals and Major Regions | 1970 | 2016 | Variation 1970-2016 (%) |

Belo Horizonte | 2,09 | 1,41 | -32,5 |

Brasília | 1,26 | 3,76 | 198,4 |

Rio de Janeiro | 12,84 | 5,26 | -59,0 |

São Paulo | 21,23 | 10,96 | -48,4 |

Vitória | 0,44 | 0,35 | -20,5 |

Total of Capitals | 49,2 | 32,9 | -33,1 |

Brasil | 100 | 100 | - |

Source: Rio de Janeiro (2018).

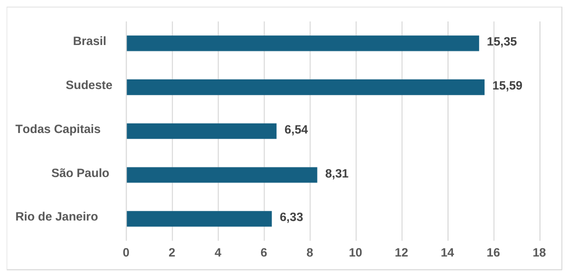

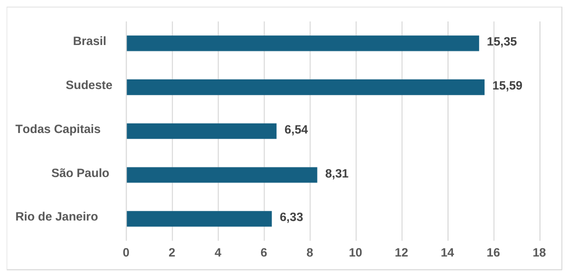

The weak industrial activity of the city of Rio de Janeiro can also be verified by analyzing the percentage distribution of jobs in manufacturing activities compared to Brazil, the Southeast region, and all the country's capitals combined. In the year 2017, while in Brazil and the Southeast the share of manufacturing jobs corresponded to 15.35% and 15.59% of total jobs, respectively, in the city of Rio de Janeiro this participation was only 6.33%, below São Paulo, with 8.31%, and even below the average of all the country's capitals, 6.54% (Graph 1) (Osório, 2018).

Graph 1: Share (%) of Manufacturing Jobs - 2017

Source: Osório (2018).

As mentioned, the repercussions of this condition are felt in the structure of the Rio de Janeiro labor market, with high levels of informality and unemployment, which disproportionately affect the most vulnerable classes and social groups.

Ottoni et al. (2020) show that the Rio de Janeiro labor market, in recent years, has suffered from serious problems, including high and often long-term unemployment, in addition to high informality. Before the pandemic, at the end of 2019, unemployment was already at 12% and disproportionately affected the poorest, black people, women, the less educated, and young people. The percentage of unemployed people in Rio who had been looking for work for more than a year jumped from 42.3% at the end of 2016 to 54.5% at the end of 2019. The authors also show that the percentage of workers in informal employment was the highest among the capitals of the South and Southeast at the end of 2019 (RIO DE JANEIRO, 2022, p. 118).

The city reached the impressive mark of more than 1 million informal workers between 2017 and 2020, more than 1.1 million in the last quarter of 2019 and the first of 2020, with this number only reducing during the beginning of the pandemic (RIO DE JANEIRO, 2022), when many activities were interrupted as a consequence and the flow of people was drastically reduced, particularly affecting the informal labor market.

If in the pre-pandemic period, between 2016 and the beginning of 2020, the number of employed workers in Rio varied between 3 and 3.2 million, the number of people of working age outside the labor force, individuals of working age who are not employed nor actively seeking work, in the same period hovered around 2.2 million (RIO DE JANEIRO, 2022). That is, for every employed worker, there was approximately 0.7 people of working age outside the labor force.

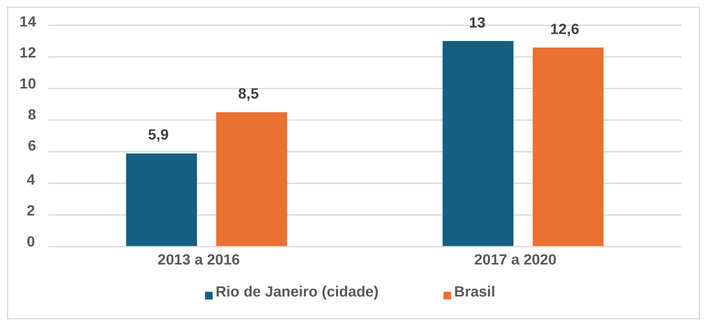

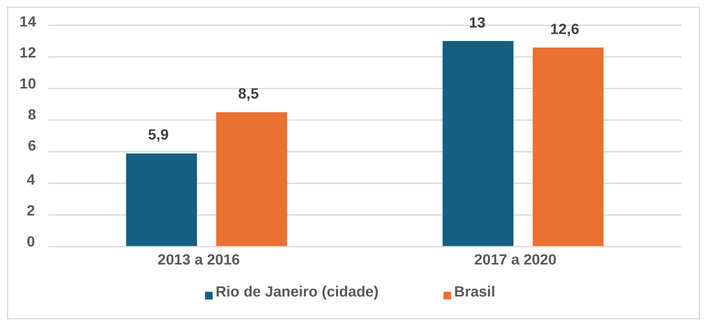

As for the unemployed workers, people of working age who are not working but are available and actively seeking employment, between 2016 and the beginning of 2020 the total number varied around 450 thousand people (RIO DE JANEIRO, 2022), which represents about 13% of Rio's economically active population. Compared to Brazil, the city of Rio de Janeiro showed a worsening of its indicators in this regard. If between 2013 and 2016 its average unemployment rate was considerably lower than the country's, from 2017 to 2020 the situation reversed, with Rio's average unemployment rate surpassing Brazil's, 13% against 12.6%, respectively (Graph 2).

Graph 2: Average Unemployment Rate (%)

Source: Rio de Janeiro (2022).

Obviously, this general picture of the Rio de Janeiro labor market tends to translate, from a social point of view, into high levels of inequality, where a considerable portion of the population finds itself in a situation of vulnerability and poverty.

According to a study prepared by the former Municipal Secretariat for Economic Development, Innovation and Simplification (SMDEIS), using research and data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), even in the pre-pandemic period the number of vulnerable people[3] in the city of Rio de Janeiro showed considerable growth. Between the last quarter of 2016 and the fourth quarter of 2019, almost 500,000 residents were included in this condition, rising from just over 1.3 million people to about 1.7 million, peaking in the first quarter of 2020, at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, with almost 1.8 million residents in a situation of vulnerability (RIO DE JANEIRO, 2022).

Bringing these economic-social indicators and elements into a territorial perspective, the profound inequalities that mark the city of Rio de Janeiro become clear, especially when analyzing and relating the distribution of the population with economic activities and jobs in the municipality.

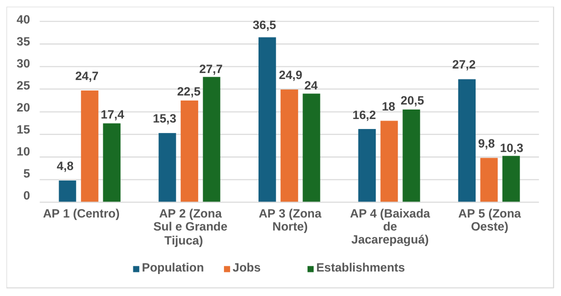

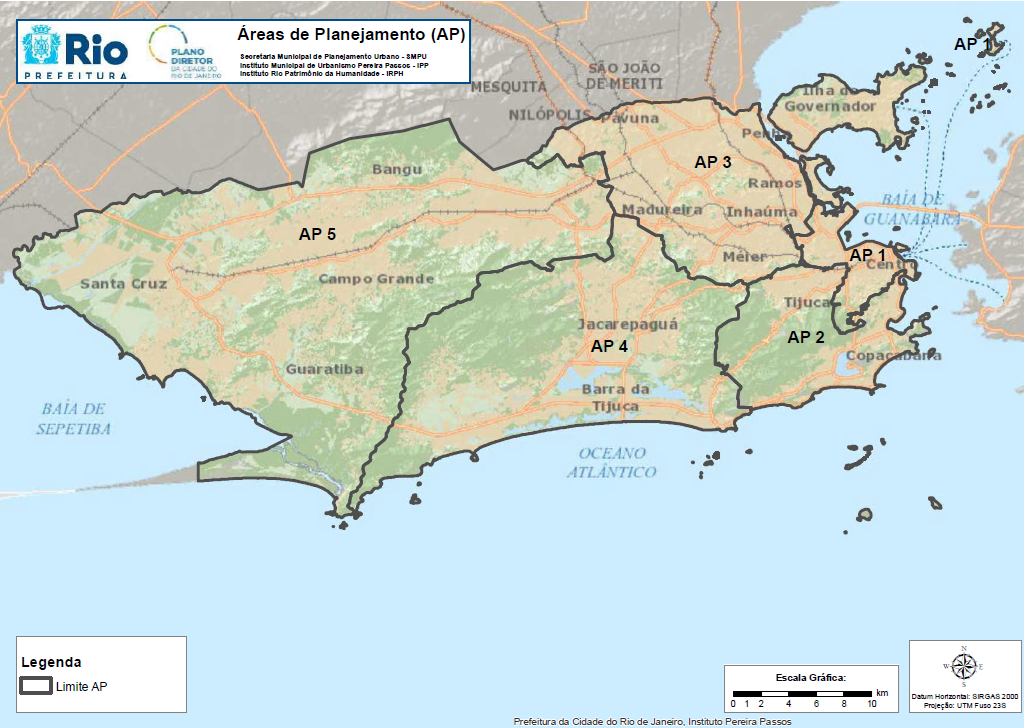

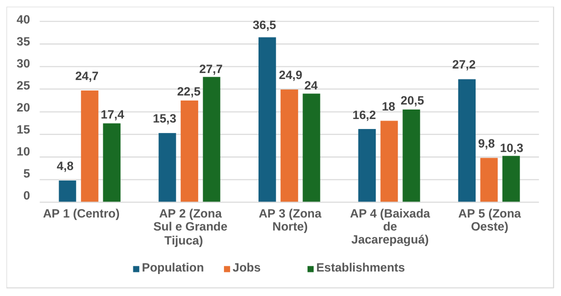

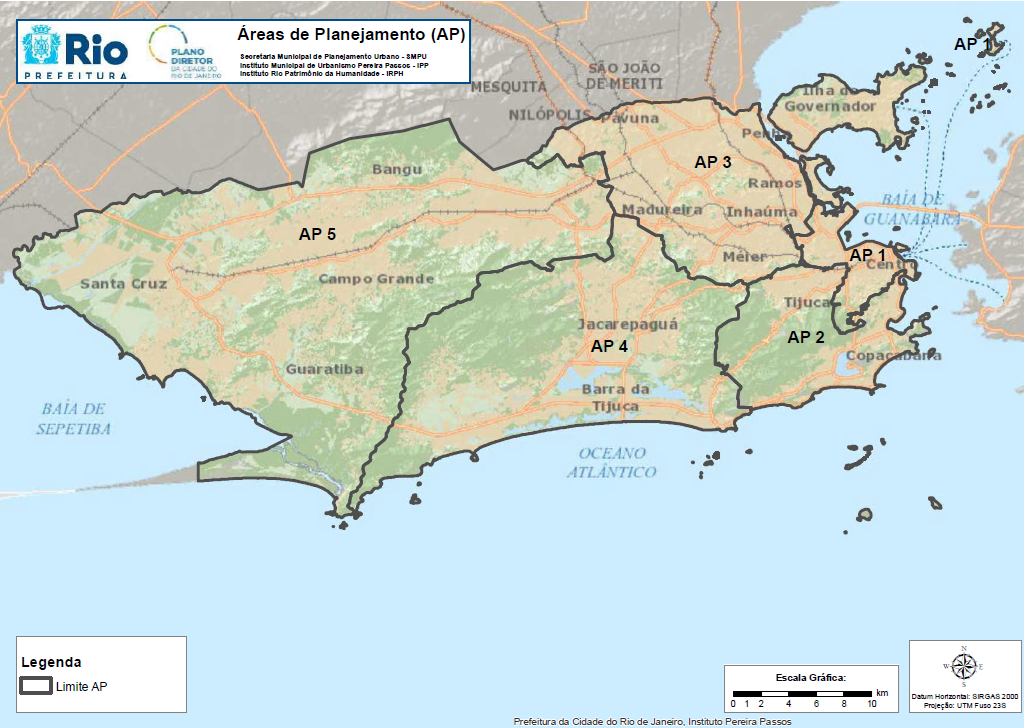

Graph 3 demonstrates that, adopting the city's Planning Areas (APs - Áreas de Planejamento)[4] as a reference (see Figure 1), most of Rio's population is located in AP 3 and AP 5, the North Zone and West Zone (excluding Barra da Tijuca and Jacarepaguá)[5], respectively, together accounting for about 63.7% of the total population. At the other extreme appears AP 1, the Center, with the lowest population concentration, not reaching 5%, while AP 2 (South Zone and Greater Tijuca) and AP 4 (Baixada de Jacarepaguá) each hold around 15% to 16% of the city's population.

However, when analyzing economic activity and the labor market, paradoxically, only 34.7% of formal private sector jobs[6] and 34.3% of establishments are located in AP 3 and 5, the most populous, while AP 1, the least populous, is the planning area that alone concentrates the most jobs and establishments in the city. Similarly, APs 2 and 4 also showed a higher participation in jobs and establishments than in the city's population, although with much smaller differences, with AP 4 showing the greatest balance, with its shares varying between 16.2% (population) and 20.5% (establishments).

Graph 3: Territorial Distribution of Population (2020), Formal Private Sector Jobs[7] (2019) and Establishments (2019) by Planning Area (AP) of Rio de Janeiro (%)

Source: Rio de Janeiro (2022).

Figure 1: Planning Areas (AP) of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro

Source: Rio de Janeiro (2024).

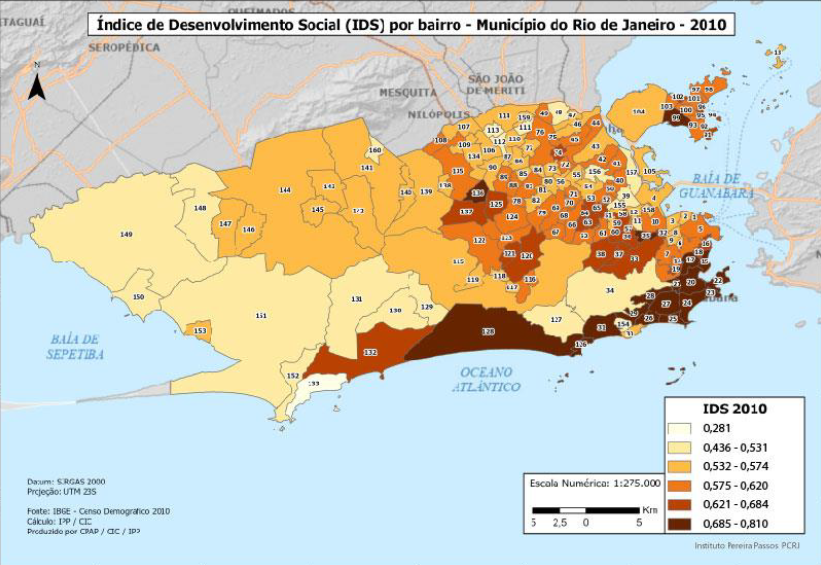

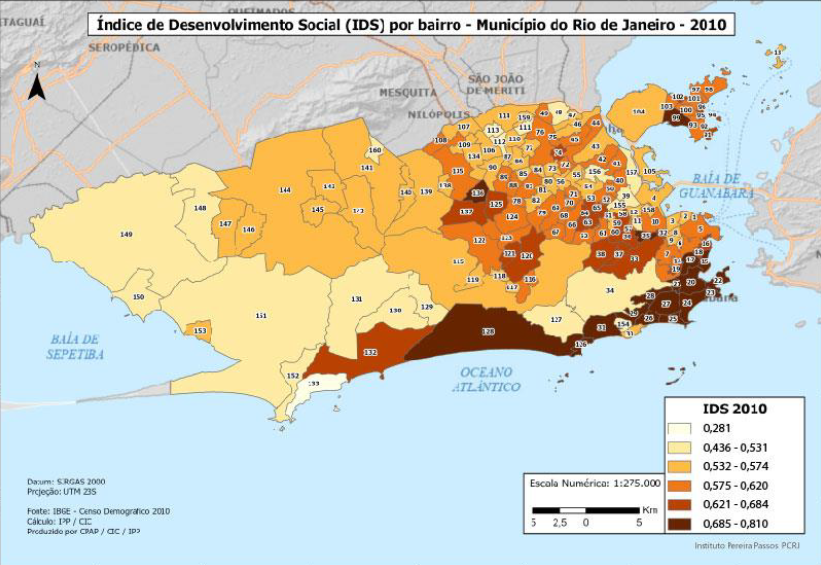

In dialogue with social and urban indicators, in this case using the Social Development Index (IDS)[8] prepared by the Pereira Passos Institute as a reference (see Figure 2), it is noticeable that the neighborhoods located in the APs where the population share far exceeds the share of jobs and establishments (AP 3 and 5) are precisely those with the worst IDS indicators. On the other hand, the neighborhoods with the highest IDS are located mainly in AP 2 and 4, with emphasis on the neighborhoods of the South Zone of the city and Barra da Tijuca.

Figure 2: Social Development Index (IDS) Map by Neighborhoods of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro - 2010

Source: Instituto Pereira Passos (2024).

These data, viewed together, evidence a notable imbalance in the distribution of economic activities in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro and a profound social and urban inequality, with few neighborhoods concentrating the best living conditions, while the majority of the city still falls far short, marked by high rates of labor informality and urban precariousness.

Thus, it is possible to affirm that the main challenge for promoting economic and social development in the city of Rio de Janeiro necessarily involves the development of its productive forces through a new impulse of industrialization that occurs, primarily, based on a more balanced distribution of economic activities and the realization of large investments in multiple projects capable of moving towards the universalization and equalization of access to employment, infrastructure, facilities, and quality urban services throughout the municipal territory.

Towards a new strategic conception of development: projectment as the path

Once reality is understood in its main aspects and contradictions, the next step in the task of transforming it requires, as a foundation, a scientific conception capable of apprehending this diagnosis and converting it into a strategy guiding political and institutional action. The proposition underpinning this article is methodologically anchored in the dialectical and historical materialist conception, which emphasizes, on one hand, the interaction between human beings and nature, shaping the productive forces; and on the other, the interactions within society itself, which configure social relations. These two dimensions, viewed through the prism of production, articulate and ultimately form a material base, understood as the [infra]structure[9], upon which the superstructure is erected, comprising, among other elements, the political and institutional sphere. However, it is important to consider that the superstructure not only stems from the [infra]structure but, dialectically, also exerts a reciprocal influence upon it.

According to the materialist conception of history, the ultimately determining element in history is the production and reproduction of real life. […] The economic conditions are the infrastructure, the base, but various other vectors of the superstructure (political forms of the class struggle and their results, namely constitutions established by the victorious class after the battle, etc., legal forms, and even the reflections of these struggles in the minds of the participants, such as political, legal, or philosophical theories, religious conceptions and their subsequent development into systems of dogmas) also exercise their influence on the course of the historical struggles and, in many cases, preponderate in determining their form. There is an interaction between all these vectors among which there are a myriad of accidents (i.e., things and events whose connection is so remote, or even impossible, to prove that we can regard them as non-existent or neglect them in our analysis), but that the economic movement finally asserts itself as necessary. (Engels, 1890, our emphasis)

It is by considering this space of relative autonomy for human capacity for elaboration and intervention in the course of material reality, understanding politics as superstructure and the terrain of the possibility of achieving "awareness of the problems and conflicts" in society, with the aim of "solving them" (Lefebvre, 2020, p. 214-215; Boa Nova, 2024a), that this article aims to contribute to the formulation of a new strategic conception of political-institutional intervention aimed at transforming the processes of production, circulation, and distribution of goods and services in society, or in Engels' terms, the processes of "production and reproduction of real life" (Engels, 1890).

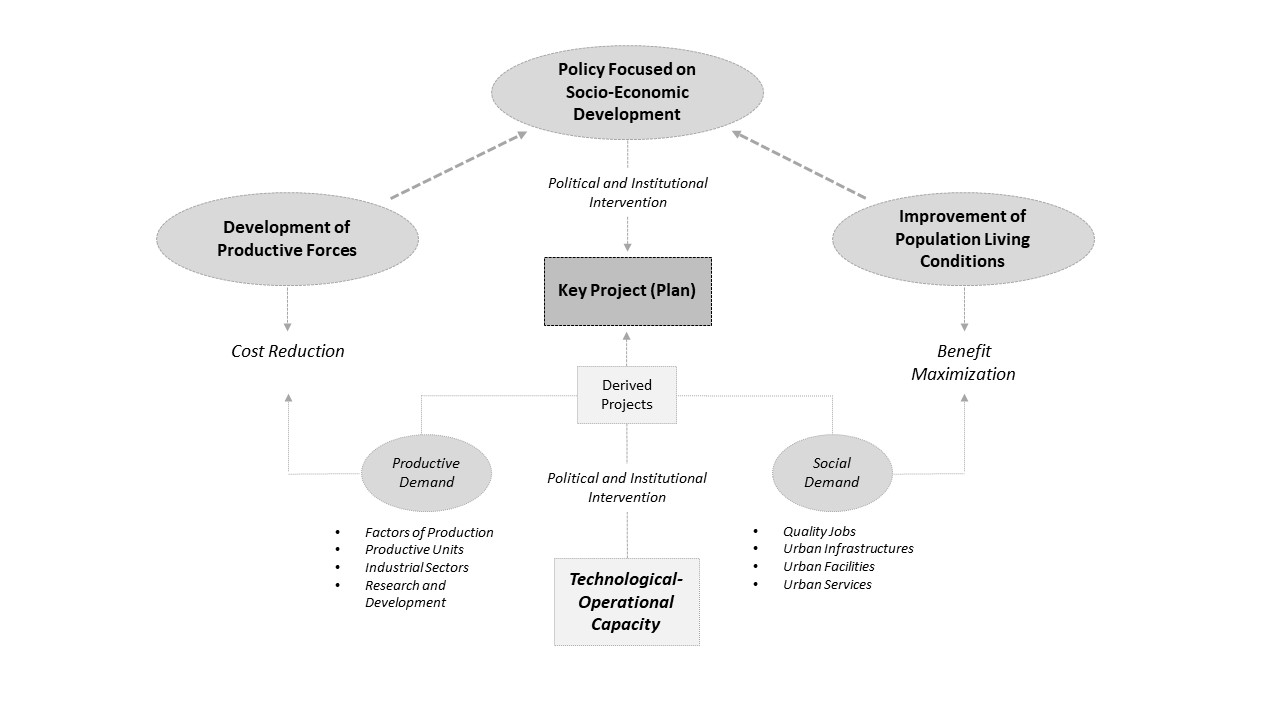

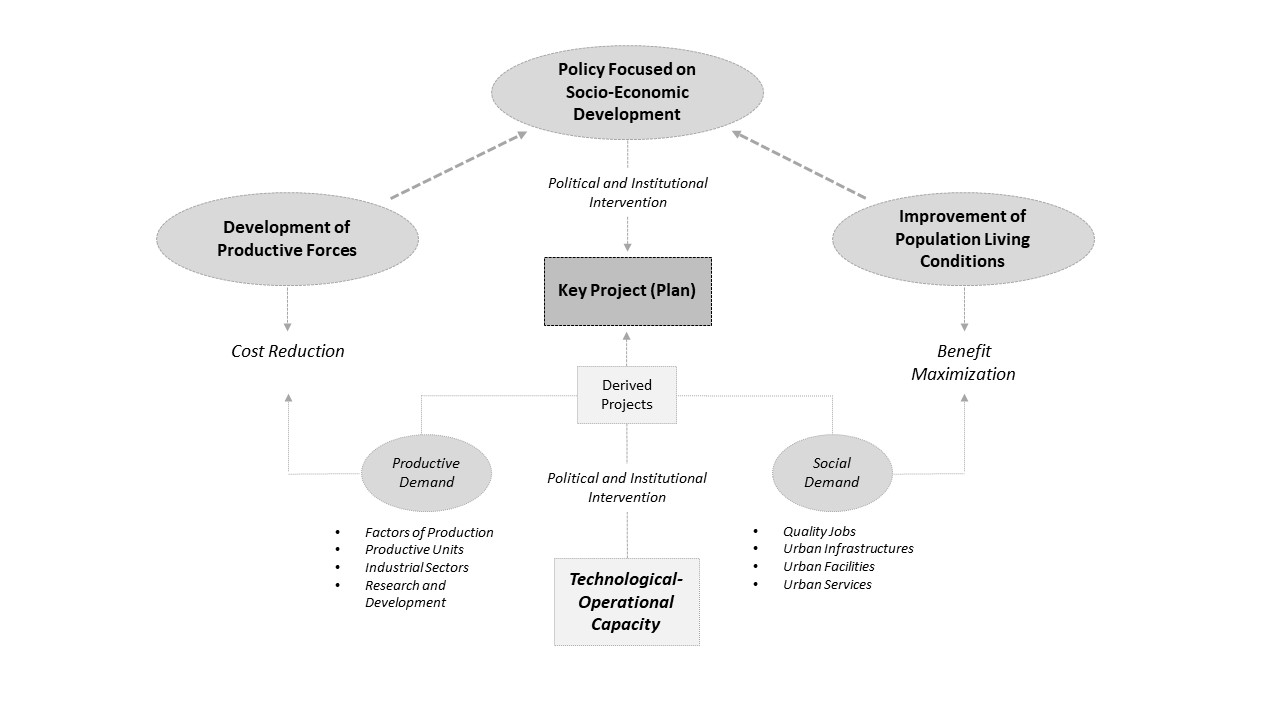

As already indicated, to be effective in addressing the main contradictions in question in Rio de Janeiro, such a strategy must articulately and inseparably link the development of productive forces and the improvement of the population's living conditions. It must conceive the advancement of productive capacity as an indispensable material requirement to sustain and expand this improvement in the realm of social life reproduction. In this sense, the option made in this essay is to use the concept of projectment, elaborated by Rangel (2012) back in the mid-last century, but recently enriched and updated by Elias Jabbour and associated researchers through contributions on the "New Economics of Projectment" (Jabbour et al., 2024; Jabbour & Capovilla, 2024; Jabbour et al., 2023; Jabbour & Moreira, 2023; Jabbour et al., 2020), as a foundational element of this proposed strategy for the economic and social development of Rio, and of Brazil, for the coming decades.

The contribution provided by the use of the concept of projectment occurs, first, through the recognition of the strategic position held by projects as an instrument of political and institutional intervention in the dynamics of economic and social development. More than, for example, laws and plans, which are more in contact with the domain of abstractions, diagnosis, systematization and elaboration of concepts, proposition of guidelines, norms and principles, projects are located in the zone of practice, of direct intervention in the processes of production (of goods and services) and (social) reproduction proper.

[...] the project is, or can be, the confirmation, through practice, of the correctness of the plan, of planning as a product of human knowledge transformed into human intervention in reality, in nature and in society itself, through the project. Without a plan, the project loses coherence and has its potential limited – "isolated, it means nothing" (Rangel, 2012, p. 195) – but it is through the project that planning acquires the opportunity to confirm and consolidate itself as a dynamic and as a process. (Boa Nova, 2024a, p. 62)

A second contribution of the concept of projectment refers to the identification, by Rangel (2012), of two categories, cost and benefit, as fundamental components of the project. Basically, costs refer to the resources consumed in the execution of a project, the factors of production, to use a term from neoclassical microeconomics, or the expenses, in an accounting and financial view of productive activity. Whereas benefits are the resources produced, created in the execution of the project – they are the products themselves, or the revenues, again in accounting-financial language, which should meet the social needs and demands for such products in the form of goods and services.

So that, on one hand, projectment has the task of reducing the project's costs as much as possible. This should happen through the development of productive forces measured by the increase in labor productivity – the capacity to produce more with the same or less quantity of labor, which reduces the value and consequently the cost of the final products. On the other hand, projectment has the task of increasing the project's benefits as much as possible, i.e.: "maximize the benefit" (Rangel, 2012, p. 405). This requires permanent research into social demand, which is constantly evolving, and "means and ways of specifying and quantifying the product to be obtained" in order to "produce goods necessary [...] for the satisfaction of a need" – which therefore possess utility and contribute to ensuring the "structure of demand" is matched by a "structure of supply" (Rangel, 2012, p. 405).

It is not enough, therefore, to multiply the production of goods, but to produce necessary goods. The country does not enrich itself by the simple expansion of the physical volume of its production, if the increase does not correspond to the satisfaction of any need, if it does not contain utility. [...] Every economy always has what we conventionally call a 'structure of demand', to which a 'structure of supply' must correspond. The execution of a new project does not become necessary, unless we discover a discrepancy between the two – a current or potential discrepancy. (Rangel, 2012, p. 405-406)

It is precisely the discrepancy between the structures of demand and supply that gives rise to "investment opportunities" (Rangel, 2012, p. 406) as a means of supplying society with the goods and services it needs. The project, in this context, is configured as the form through which investment materializes (Rangel, 2012, p. 282). For the project designer, whose role is to ensure scientificity in the allocation of resources, these structures are an objective given: it is not their role to judge them, but rather to know them through research (Rangel, 2012, p. 406), so that the investments made translate into social utility and, therefore, into collectively appropriable benefits.In other words, the function of projectment can be understood as the search for answers to two fundamental practical questions: "What to produce?" and "How to produce?". The first refers to the need to order the allocation of resources, i.e., to decide in which projects to invest with a view to maximizing social benefits. The second refers to the definition of the production technique, i.e., the choice of the combination of factors that allows reducing, as much as possible, the execution costs of the projects.

The third dimension of projectment to be absorbed into the development strategy proposed through this article stems from the identification of two types of projects: complex projects, or key projects, a term that will be used here, and derived projects, with both conforming a development dynamic based on projects that derive more projects.

Regarding the first, key projects, "Rangel establishes a relation of relative identity between plan and project, and, more than that, he does so from a process vision of the act of projecting – that is, a vision of 'projectment'" (Boa Nova, 2024a, p. 230). They are projects from which, forward, and for which, backward, a series of multiple and diverse projects derive – "projects of derived demand" (Rangel, 2012, p. 396). A kind of anchor project, from which many other smaller projects branch out, giving it real contours. In this regard, Rangel gave the following example:

A complex project like the National Electrification Plan allows, for example, to address the demand for electrical equipment for a considerable period, unfolding into the creation of the corresponding industry, which would imply considerable savings in foreign exchange. This industry, a child of the derived demand from the electricity projects, might appear uneconomical if it had to work for an unknown market, but prove exceptionally economical under the other hypothesis. (Rangel, 2012, p. 281, our emphasis)

As for derived projects, they can be divided into two typologies: productive derived demand projects and social derived demand projects. "In the first case, these are the 'backward' demand projects, aimed at forming a supply structure of productive goods and services that meet the demand of the complex project". They can range from factors of production, productive units, to entire industrial sectors, research and development activities. Basically, they seek "to offer answers to the questions of 'how to produce such complex projects?'; 'which sectors, branches and economic-productive activities', in other words, 'which projects must be created in order to make the construction of the [key projects] possible?'" – "which relates to the need to produce at the lowest possible cost" (Boa Nova, 2024a, p. 240).

In the second case, of social derived demand projects, "these are the 'forward' demand projects, aimed at forming a supply structure of social goods and services that meet the demand of the complex projects". They can therefore be products for individual or collective consumption, as are, for example, in the latter case, infrastructure and urban facility projects, also involving the social dimension of the need for job generation. "They thus seek to offer an answer to the questions regarding 'what to produce to achieve the purpose of the complex project?'", 'which products – goods, services – or "urban projects must be created?'" – "such a task relates to the need to produce the greatest possible benefit" (Boa Nova, 2024a, p. 240-241).

[…] regarding the relationship between projects considered complex and derived, […] two typologies of projectment can be identified: those formed by productive demand projects and those formed by social demand projects. Both refer to demands derived from the complex projects, and the latter as key projects around which all others gravitate (Boa Nova, 2024a, p. 239-240)

Finally, a fourth dimension to be incorporated refers to the concept of the New Economics of Projectment. Elaborated by Elias Jabbour while analyzing the Chinese development process, this concept brings with it an emphasis on technological innovation processes – especially with the emergence of Artificial Intelligence (AI), Big Data and the Internet of Things, both as an elevation of human dominion over nature, developing the productive forces (Jabbour & Capovilla, 2024), and as a condition for the emergence of new and superior forms of economic planning (Jabbour & Moreira, 2023). So that technological innovation is not only a means to increase labor productivity and the consequent capacity to produce wealth. It also becomes an instrument that allows expanding the conditions for political and institutional intervention in the processes of production, circulation and distribution in society through the practice of projectment: the capacity to master the process of conceiving projects that demand more projects, in order to promote economic and social development.

Figure 3: Strategic conception of economic and social development based on the concept of projectment

Source: own elaboration.

Proposal for an economic and social development strategy for Rio de Janeiro: projecting the city's future

Having presented the strategic conception of development based on the concept of projectment, this section aims to deepen the reflection and outline alternatives and proposals for political and institutional intervention in the processes of production, circulation, and distribution in the territory of Rio de Janeiro, which should involve the city, the metropolitan region, and even the state of Rio de Janeiro. For this purpose, we intend to identify the key project that should guide the entire approach, its tasks, axes, guidelines, and strategy, as well as the derived projects that give it concrete and operational contours[10].

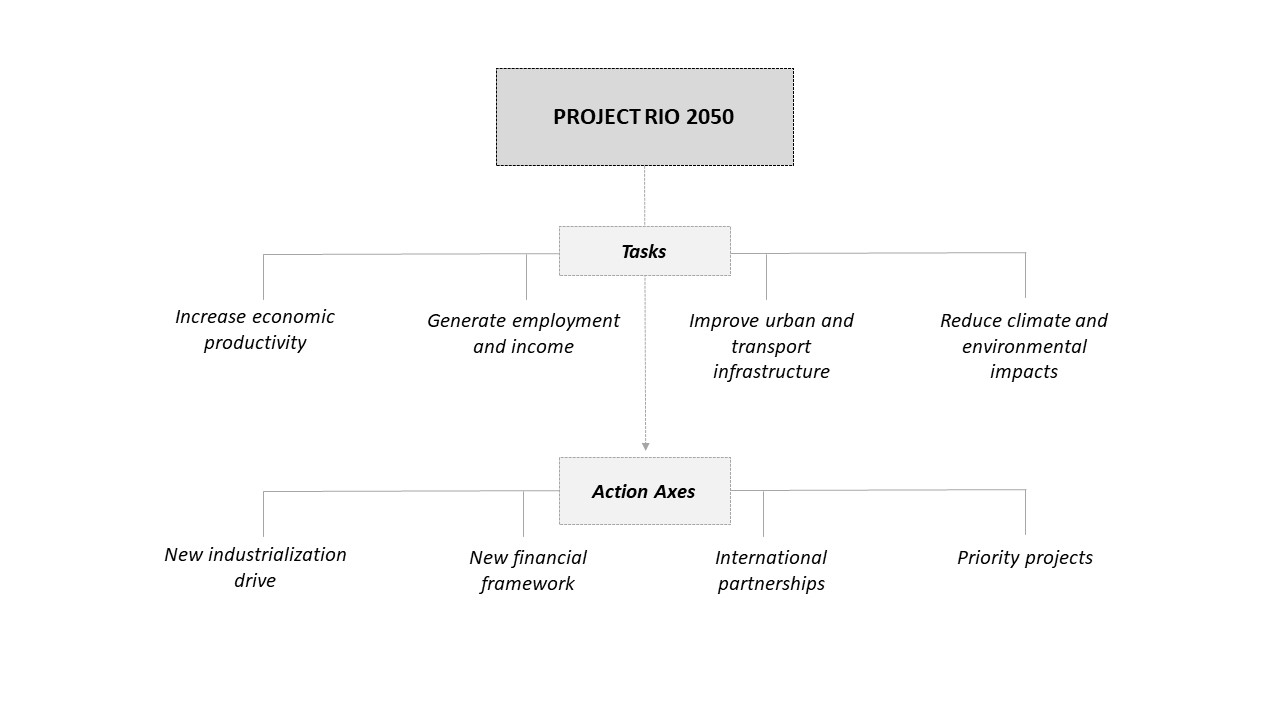

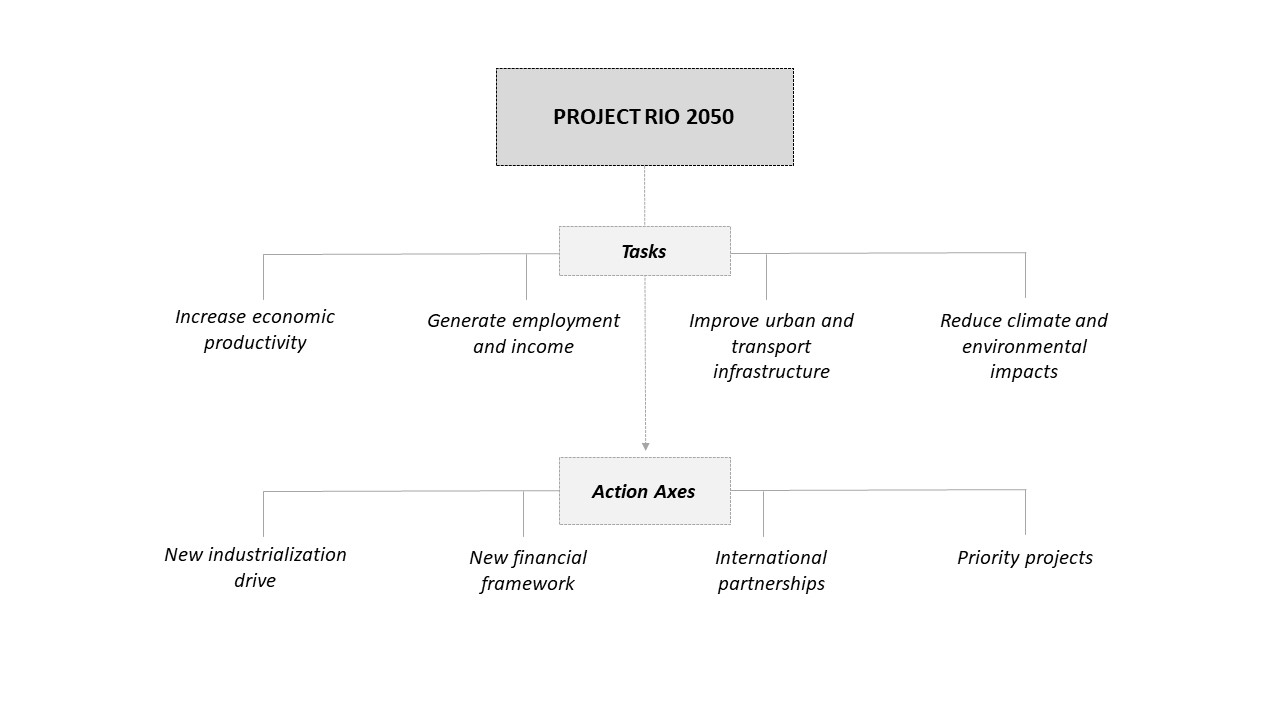

The starting point consists of defining what is meant by a key project, a kind of structuring plan, from which the other formulations and proposed actions will unfold. We opted to adopt a "name-slogan" capable of contributing to the mobilization of society and political-governmental institutions and simultaneously expressing the dimensions of time and space: the territory where the transformations are intended to be implemented, and the historical perspective guiding medium and long-term development planning. Thus, as a first suggestion, the Rio 2050 Project emerges. A future project, anchored in the challenges of the present, with the objective of promoting the economic and social development of Rio de Janeiro in the coming decades.

Based on the diagnosis of the main contradictions and obstacles that currently hinder the economic and social development of Rio de Janeiro – on one hand, a growing and accumulated social demand for better living conditions, on the other, the difficulty in raising the level of local productive forces, limiting the capacity to generate income, wealth, and the goods and services necessary to meet these demands – it is understood that the proposed key project (see figure 4) should be guided by four main tasks.

Figure 4: Key project, tasks, and strategic axes

Source: own elaboration.

Linked to the imperative of developing local productive forces, the first and primary task, a precondition for the others, is to increase the economic productivity of Rio de Janeiro. That is, to ensure the increase of the installed productive capacity in its territory in order to create the material bases that will allow offering goods and services in sufficient quantity and quality to meet social needs. The second task focuses on confronting the high level of labor informality and precarity in Rio de Janeiro, as well as unemployment and discouragement, through job and income generation, also in quantitative and qualitative terms. In other words, to create quality jobs, with remuneration that guarantees a dignified standard of living, considering the profile and characteristics of the groups and segments of society that suffer most from precarity and unemployment.

The third task aims to offer a response to the social inequalities that manifest through an intense and glaring territorial inequality in Rio de Janeiro, as demonstrated in the diagnosis in the first section of the article. Given the imbalance in the distribution of economic activities and the concentration of the best social indicators in only a small territorial portion, notably in the South Zone and Barra da Tijuca, it becomes a task of utmost importance to improve urban and transportation infrastructure throughout the municipal and metropolitan territory.

The fourth task considers the relationship between society and the environment in the context of the climate emergencies that have affected the entire planet and also Rio de Janeiro in a particular way. Be it recurrent floods during rainy periods, landslides, as well as heat waves and extreme temperatures, which precisely affect the most vulnerable social groups, with worse housing and income conditions, as well as the perspective of sea level rise. Consequently, it is imperative to promote policies to reduce climate and environmental impacts in the urban space, linked to the challenge of the energy transition and a low-carbon economy.

From these tasks unfold the axes of action that should guide the general development strategy for Rio de Janeiro. The first and main one, which refers to the task of increasing productive capacity, is the construction of a new impulse for industrialization in the city and metropolitan region of Rio and in the territory of the state of Rio de Janeiro, an impulse which, in order to have greater chances of success, should also encompass Brazil and other regions of the country, conforming a new national and regional division of labor where Rio would be inserted fulfilling a function among the others.

The task of developing the productive forces leads to the second axis, the need to establish a new financial arrangement capable of guaranteeing the viability and sustainability of this great enterprise that would be a new impulse for industrialization. The fact is that, given the current fiscal constraints and the conduct of national monetary policy as it has been practiced by the Central Bank, the Union, the states, and Brazilian municipalities find themselves somewhat "asphyxiated" and with very limited conditions to promote sufficient investments for the installation of new productive activities.

Beyond an increase in the investment capacity of, for example, BNDES and strategic public companies, like Petrobras, or even the creation of new development banks at the state and municipal levels, as already existed in Brazil during the national-developmentalist period of the 20th century, one possibility to circumvent this situation given the current correlation of forces in national politics could be through the construction and deepening of international partnerships, with countries willing to make large investments in Brazil, especially productive investments, such as in the installation of new industrial units in the country.

The fourth and final axis refers to the elaboration and selection of projects considered priorities. Projects that should guarantee more concrete contours to the other axes mentioned, and which, therefore, should boost the industrialization of Rio de Janeiro, guide international partnerships through investments considered strategic for this purpose, and confront social and territorial inequalities through the improvement of urban and transportation infrastructure and the generation of employment and income.

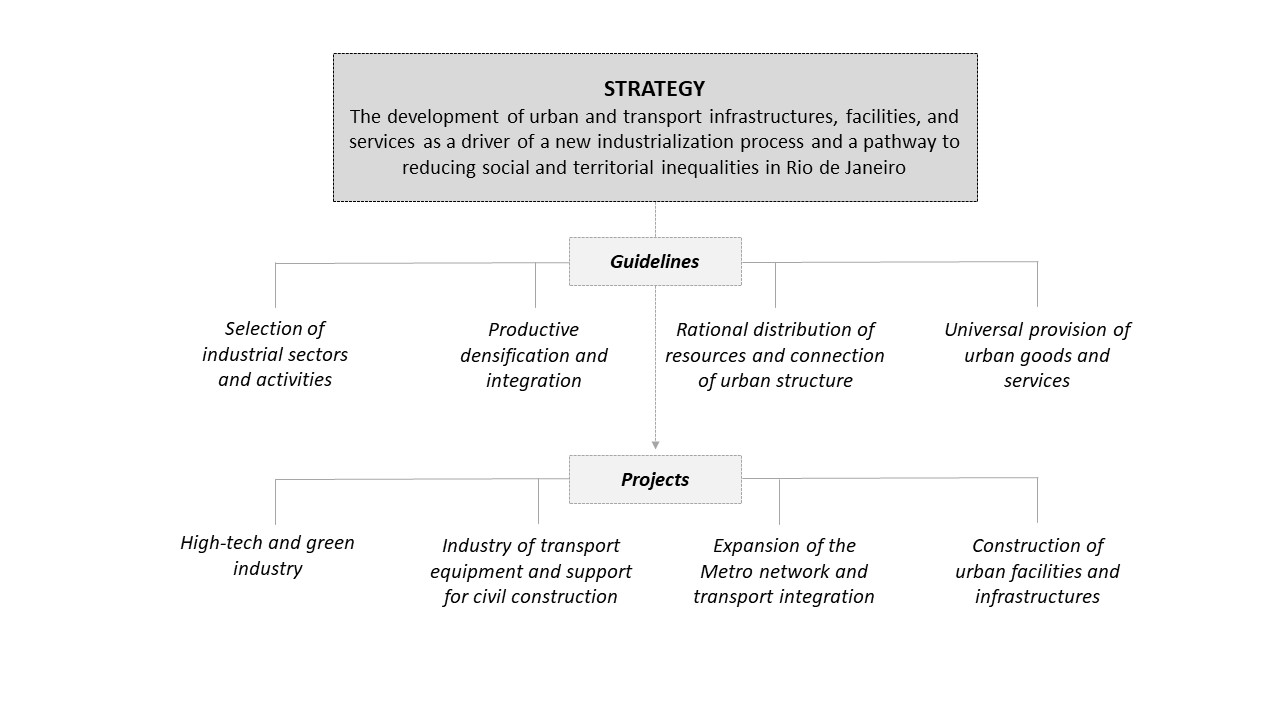

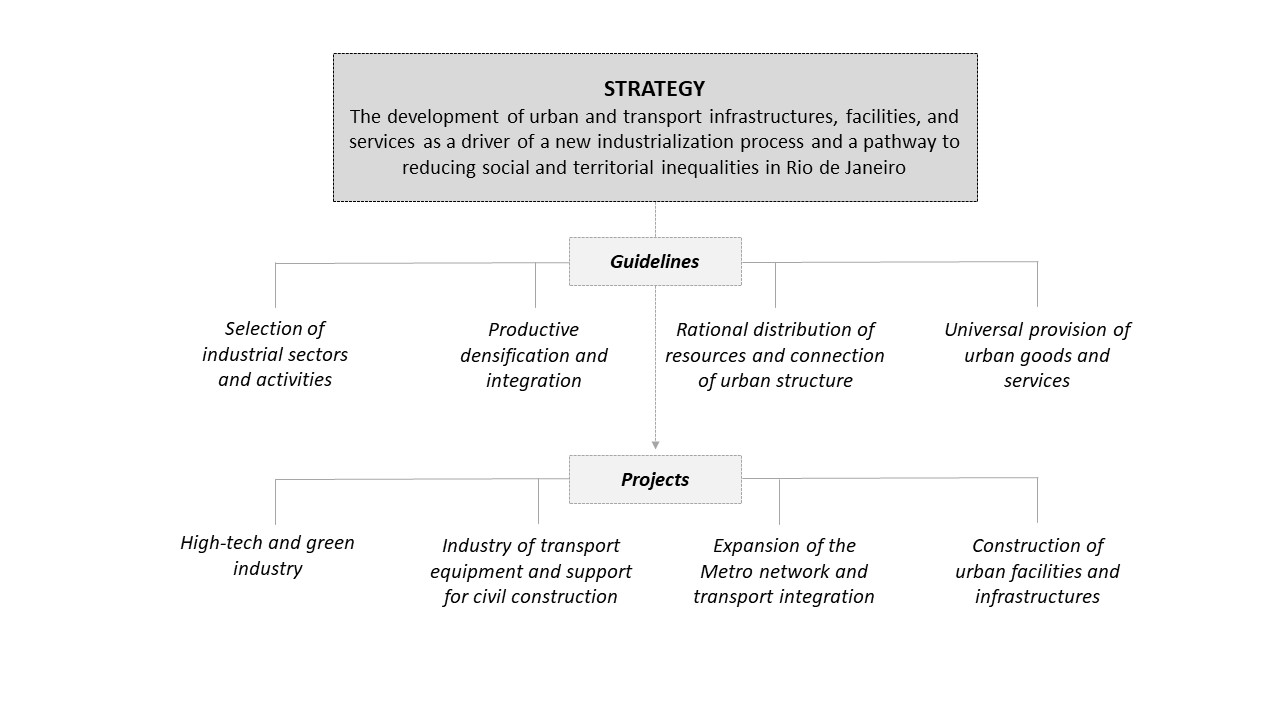

Based on these tasks and axes of action, the proposal of the Rio 2050 Project has as its general strategy to use the development of urban and transportation infrastructure and facilities as a lever for a new process of industrialization and reduction of social and territorial inequalities[11] in Rio de Janeiro in the coming decades (figure 5). That is, to build a qualitatively superior urban environment both from an economic and productivity standpoint, attracting new industries and economic activities, and from a social and environmental perspective, raising the living conditions of its population.

For this, four guidelines were indicated. The first guideline refers to the process of selecting the industrial sectors and activities that should be prioritized to achieve the objective of promoting economic and social development. It must, therefore, answer the question: "which productive sectors and activities to create and stimulate to ensure that the strategy defining the Rio 2050 Project is fulfilled?". These are the productive derived demand projects mentioned in the previous section. Just like the second guideline, promoting productive densification and linkages, which articulates with the first, adding the dimensions of location and the process of relations between industrial sectors and activities. It aims, through an effort to internalize production in the territory of Rio de Janeiro and form clusters, to fill the input-output matrix, ensuring the supply of production goods, such as machines, tools, equipment, and inputs and raw materials necessary to meet productive and social demands.

Figure 5: Development strategy, guidelines, and projects

Source: own elaboration.

The third and fourth guidelines fall within the scope of social derived demand projects, referring to the processes of social production and reproduction in the urban environment. The third guideline involves the rational distribution of resources and the connection of the urban structure, in order to equalize urban conditions and externalities in the different areas and neighborhoods of the city and metropolitan region, such as, for example, access to sanitation, health facilities, education, job supply, quality transportation, etc.

The fourth guideline, related to the previous one, aims to pursue the universalization of the supply of social and urban goods and services in the territory of Rio de Janeiro. So that the differential and monopoly rents tied to the price of land use (Marx, 2017; Ribeiro, 1997) are diminished, and the social inequalities linked to the territorial dimension of inequalities are profoundly reduced. Both refer to the sphere of distribution and redistribution of socially produced wealth, with special attention to the types of consumption that occur in a public and collective manner – consumption of the urban space and environment, properly speaking, through its urban and social facilities and infrastructures.

As a final exercise of this propositional essay, considering the recent political-institutional formulations and propositions at the national level regarding the economic and industrial development of the country evidenced in the Plano Nova Indústria Brasil (BRASIL, 2025), we opted to highlight specific projects that could be implemented, representative of productive demand and social demand, and of strategic content for the promotion of socio-economic development, and therefore, for the realization of the Rio 2050 Project and its objectives. They are:

- High-tech and green industry

Linked to mission 4 of the Plano Nova Indústria Brasil (NIB), digital transformation of industry to expand productivity, and the need to develop productive forces and increase the productivity of Rio de Janeiro's economy, the construction of a high-tech industry acquires strategic importance. More than indicating a specific sector or activity, the essential thing is to consider the ongoing transformations in the world, identifying emerging industries and productive services with high technological content, which, in addition to increasing the product and income generated in the city, also play a role as a facilitator of the projectment process itself and the improvement of social and environmental conditions in the urban space. These are the cases of activities related to the sectors of Artificial Intelligence (AI), Big Data, Internet of Things, which can be appropriated by public institutions through their incorporation into governance processes, aiming at the construction of a smart city, and the so-called green industry, focused, for example, on the generation and storage of clean and renewable energy, electrification of services and transport, and research and development activities in biotechnology, which links to mission 5 of the NIB: Bioeconomy, decarbonization, and energy transition and security to guarantee resources for future generations.

- Transport equipment industry and support for civil construction

Associated with mission 3 of the NIB, related to Infrastructure, sanitation, housing, and sustainable mobility for productive integration and well-being in cities, aiming to contribute to the production of social and urban goods and services that will allow universalizing access and better distributing resources in the territory of the city and metropolitan region, it becomes imperative to promote the installation of activities for the production of transport equipment, related mainly to rail transport, such as the manufacture of trains, wagons, locomotives, rails, sleepers, traction and signaling systems, equipment for control and automation systems, and support for civil construction – construction materials industry, metal and structural components, machines, equipment and tools, electrical, hydraulic and sanitation, logistics –, making Rio de Janeiro a kind of hub for sectors and activities essential for the execution of infrastructure, housing, public buildings, and mobility works, not only for the city and its regions of influence but also for Brazil as a whole.

- Expansion of the subway network and integration of transports

Also linked to mission 3 of the NIB, project 3 aims to promote the connection of the complex and unequal urban structure and its multiple functions, uses, and activities arranged in the territory. Considering that the areas with the highest population participation are those with the lowest participation in the distribution of jobs, and the reverse is true, which requires an effective mobility system, a project to expand the subway network is necessary, still far below demand and currently covering only a minority portion of the neighborhoods and areas of Rio de Janeiro and its metropolitan region. As well as the integration of different transport modes, mainly the lines of the subway itself, the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), the Light Rail Vehicle (VLT), and bike paths, in order to equalize access as much as possible, multiplying and expanding throughout the territory the positive externalities arising from it.

- Construction of urban infrastructures and facilities

Possibly the most important project, and one that truly gives meaning to the Rio 2050 key project, is the construction of urban infrastructures and facilities, also tied to mission 3 of the NIB. Acting as a kind of enabler for the supply of urban services that meet various social demands, this project assumes a double function. It serves as a basis for socio-economic development by creating, on one hand, the conditions for carrying out economic activities and, on the other, meets social needs, guaranteeing quality of life for inhabitants by promoting greater and better access to the social benefits of the urban environment. It involves, for example, the construction of infrastructures aimed at providing public utility services, such as electricity, communication, public transport, water supply, sanitation, environmental preservation, solid waste management, disaster prevention, gas supply, etc., or public works projects, such as highways, bridges, tunnels, dams, drainage systems, paving, landscaping. Furthermore, for example, educational facilities: primary and secondary schools, daycare centers, technical and vocational schools, universities; health facilities: medical posts, hospitals, care and social assistance homes; cultural facilities: theaters, cinemas, museums, libraries, cultural and entertainment centers; sports facilities: gyms, arenas, fields, tracks, gymnasiums, stadiums; public facilities: parks, squares, gardens, monuments; consumption and business facilities: commercial centers, shopping malls, markets, convention and conference centers; transport facilities: subway stations, bus, VLT, train stations, airports, heliports; and security facilities: police stations, fire stations, and civil defense stations.

As stated, these are propositions, indications of paths that can be followed through the execution of structuring policies committed to promoting economic and social development. It is important to consider the challenges that a project of this magnitude implies, both for governments at their various levels and for public and state institutions, which, for its effective realization, will need to be called upon to act with protagonism and a medium and long-term vision. In any case, it is hoped that the ideas and proposals presented in this article will contribute to stimulating debate and the elaboration of alternatives for solving the most urgent problems of the society of Rio de Janeiro, the state of Rio de Janeiro, and Brazil.

- Conclusion

More than critically analyzing a reality or even correctly identifying the main issues of our time and place, the current world and its challenges demand from social scientists, especially those in applied social sciences, such as political economy and urban and regional planning, the audacity and the ambition to offer answers to these questions with the clear objective of transforming that same reality. While it is certain that not all actions taken in this direction will be fully successful, and therefore involve taking risks, it is even more certain that abstaining from proposing concrete alternatives will tend to have even worse consequences in the medium and long term, with the deepening of the contradictions already underway.

It was with this spirit, which can well be called political and scientific commitment, that this article proposed the exercise of elaborating a strategy for the economic and social development of Rio de Janeiro for the coming decades, the 'Rio 2050 Project'. Without claiming to impose solutions or disregard the need for a deep and broad social debate on the topic, involving institutions, organized movements, and other social representations in order to elaborate a development strategy, this article proposed to act as a kind of essay, capable of bringing new elements and stimulating the qualification of the debate itself, feeding and generating new discussions as a path to consensus.

With the main objective of confronting the condition of profound social inequalities that manifest territorially in the urban environment of the city and its areas and regions of influence, the first step sought to identify the main contradiction and the respective principal aspect of this contradiction within society, in this case, of Rio de Janeiro. As already stated, from the contradiction between the growing and accumulated social demand for better living conditions and the inability to generate income, wealth, goods, and services in sufficient quantity and quality to meet these social demands lies the urgency of developing the productive forces as the main aspect of the problem.

Faced with this situation, an effort was made to affirm a scientific conception as a foundation for converting this diagnosis into a strategy guiding political-institutional intervention in the development process. For this, the concept of projectment was used, given its capacity to articulately and inseparably link the development of productive forces and the improvement of the population's living conditions by conceiving the advancement of productive capacity as an indispensable material requirement to sustain and expand improvement in the realm of social life reproduction.

Furthermore, the concept of projectment allows for conferring method and a technical dimension to the process of formulating a development strategy based on a dynamic where projects derive other projects. By highlighting the importance of establishing a key project as a kind of anchor from which many other derived projects, of productive and social demand, branch out, giving it real contours, it allows for expanding the conditions for political and institutional intervention in the processes of production, circulation, and distribution of socially produced wealth in order to promote economic and social development.

Finally, we sought to detail the content of the key project, the Rio 2050 Project, and offer better-defined elements to the proposal by identifying tasks, axes of action, guidelines, and projects as means to achieve it. The essence of this development strategy is based, in synthesis, on the elaboration and execution of urban and transportation infrastructure and facility projects as an impulse for a new industrialization process, adapted to contemporary challenges, and as a path to effectively confront the striking social and territorial inequalities in Rio de Janeiro.

It is considered that by selecting certain productive sectors and activities, whether in industry or services, and encouraging their reproduction in order to simultaneously generate wealth, create jobs, and meet the demand for collective and individual goods and services, a new type of development dynamic can be established, where the centrality of the social question, through meeting social demands, aligns with the primacy of the task of developing the productive forces, and is expressed in the form of a socially more equitable and higher quality urban environment for Rio de Janeiro and its inhabitants.

May from this essay, a first step, new ideas and propositions unfold, moving towards confronting the greatest challenges and problems of our time, especially for Rio de Janeiro, the synthesis of Brazil.

References

BOA NOVA, Vitor. Socialismo chinês, do planejamento aos projetos urbanos e de transporte: a planificação do desenvolvimento (urbano-regional) desigual como expressão (territorial) da nova economia do projetamento. Thesis (Doctorate in Urban and Regional Planning) – Instituto de Pesquisa e Planejamento Urbano e Regional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2024a.

BOA NOVA, Vitor. O planejamento urbano-regional chinês como eixo de desenvolvimento econômico e social. Entre-Lugar, v. 15, n. 30, p. 203-227, 2024b.

BOA NOVA, Vitor. Socialismo, planificação do desenvolvimento desigual e a expressão territorial da nova economia do projetamento na China. Princípios, v. 43, n. 171, p. 75-93, 2025.

BRASIL. Ministério do Desenvolvimento, Indústria, Comércio e Serviços. Nova indústria Brasil – forte, transformadora e sustentável: Plano de Ação para a Neoindustrialização 2024-2026 / Ministério do Desenvolvimento, Indústria, Comércio e Serviços, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Industrial (CNDI), 1ª edição, revisada e atualizada. -- Brasília : CNDI, MDIC, 2025.

CANO, W. Desconcentração produtiva regional do Brasil 1970-2005. 1ª Edição. São Paulo: UNESP, 2008.

DINIZ, Clélio Campolina. Desenvolvimento poligonal no Brasil: nem desconcentração, nem contínua polarização. Nova Economia, v. 31, n. 1, p. 35-64, 1993.

ENGELS, Friedrich. Carta a Joseph Bloch, 21 de setembro de 1890. In: Marxists Internet Archive. [s.d.]. Available at: https://www.marxists.org/portugues/marx/1890/09/22.htm. Accessed on: 6 jun. 2025.

HASENCLEVER, L.; PARANHOS, J.; TORRES, R. Desempenho econômico do Rio de Janeiro: trajetórias passadas e perspectivas futuras. Dados – Revista de Ciências Sociais, Rio de Janeiro, v. 55, n. 3, p. 681-711, 2012.

INSTITUTO PEREIRA PASSOS. Adaptação metodológica do IDS: rumo à análise comparativa com o Censo 2022. Nota técnica. Rio de Janeiro: IPP, 2024.

JABBOUR, Elias; BOA NOVA, Vitor; VADELL, Javier. The ‘Chinese Path’: uneven development, projectment, and socialism. Caderno Metrópoles, v. 26, n. 59, p. 377-399, 2024.

JABBOUR, Elias; CAPOVILLA, Cristiano. Pressupostos dialéticos acerca do socialismo e projetamento na China de hoje. Economia e Sociedade, v. 33, n. 3, p. e281848, 2024.

JABBOUR, Elias; DANTAS , Alexis; ESPÍNDOLA, Carlos e VELLOZO, Júlio. The (New) Projectment Economy as a Higher Stage of Development of the Chinese Market Socialist Economy. Journal of Contemporary Asia, v. 53, n. 5, p. 767–88, 2023.

JABBOUR, Elias; DANTAS, Alexis; ESPÍNDOLA, Carlos e VELLOZO, Júlio. A (Nova) Economia do Projetamento: o conceito e suas novas determinações na China de hoje. Geosul, v. 35, n. 77, p. 17-48, dez. 2020.

JABBOUR, Elias; MOREIRA, Uallace. From the national system of technological innovation to the “New Projectment Economy” in China. Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, v. 43, p. 543-563, 2023.

LEFEBVRE, Henri. O pensamento de Lênin. São Paulo: Lavrapalavra, 2020.

LESSA, Carlos. O Rio de todos os Brasis: uma reflexão em busca de auto-estima. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2000.

MAO, Tsé-Tung. Sobre a prática e sobre a contradição. 1 ed. São Paulo: Expressão Popular, 1999.

MARX, Karl. O Capital: crítica da economia política. Livro II: O processo de circulação do capital. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial, 2014.

MARX, Karl. O capital: crítica da economia política. Livro III: O processo global da produção capitalista. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial, 2017.

OSÓRIO, Mauro. Características e estratégia para a cidade e a região metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: CTPD (79ª Reunião), 07 nov. 2018. Available at: http://www.rio.rj.gov.br/dlstatic/10112/6438610/4226413/79CaracteristicaseestrategiaparaacidadeearegiaometropolitanadoRiodeJaneiroMauroOsorio.pdf. Accessed on: 20 may 2025.

OTTONI, B.; DUQUE, D.; ULYSSEA, G. “Mercado de Trabalho”, In: Mello, E. B.; Vieira, A. G.; Barboza, R. M. (orgs.), “Maravilhosa para todos: políticas públicas para o Rio de Janeiro”, p. 151-180. 2020.

RANGEL, Ignácio. Obras reunidas. Volume 1. 3 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto, 2012.

RIBEIRO, Luiz Cesar de Queiroz. Dos cortiços aos condomínios fechados: as formas de produção da moradia na cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1997.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Município). Lei Complementar nº 270, de 16 de janeiro de 2024. Plano Diretor de Desenvolvimento Urbano Sustentável do Município do Rio de Janeiro. Diário Oficial do Município do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 17 jan. 2024. Available at: https://doweb.rio.rj.gov.br. Accessed on: 28 may 2025.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Município). Secretaria Municipal de Desenvolvimento Econômico, Inovação e Simplificação. Desenvolvimento econômico do Rio: diagnósticos e ações. Ano I. Rio de Janeiro: SMDEIS, 2022.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Município). Secretaria Municipal de Urbanismo. Diagnóstico intersetorial integrado da cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Relatório Técnico. Rio de Janeiro: SMU, 2018.

SILVA, R. D. Indústria e desenvolvimento regional no Rio de Janeiro 1990-2008. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV, 2012.

SINGER, André. Cutucando onças com varas curtas: o ensaio desenvolvimentista no primeiro mandato de Dilma Rousseff (2011-2014). Novos estudos CEBRAP, n. 102, p. 39-67, 2015.

About the Authors

Vitor Boa Nova: Special Projects Advisor at the Municipal Institute of Urbanism Pereira Passos (IPP), PhD in Urban and Regional Planning, Master in Urban and Regional Planning, and specialist in Urban Policy and Planning from the Institute of Research and Urban and Regional Planning (IPPUR) at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

Elias Jabbour: President of the Municipal Institute of Urbanism Pereira Passos (IPP). Associate Professor at the School of Economic Sciences of the State University of Rio de Janeiro (FCE-UERJ), in the Graduate Program in Economic Sciences (PPGCE-FCE-UERJ) and the Graduate Program in International Relations (PPGRI-UERJ). Between 2023 and 2024, he served as Senior Consultant to the Presidency of the New Development Bank (BRICS Bank) and was awarded the Special Book Award of China by the National Press and Publications Administration of the People’s Republic of China.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: V.V.F.B.N, E.M.K.J; Methodology: V.V.F.B.N, E.M.K.J; Formal analysis: V.V.F.B.N, E.M.K.J; Investigation: V.V.F.B.N, E.M.K.J; Writing—original draft preparation: V.V.F.B.N, E.M.K.J; Writing—review and editing: V.V.F.B.N, E.M.K.J. All authors have read and approved the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

About Coleção Estudos Cariocas

Coleção Estudos Cariocas (ISSN 1984-7203) is a publication dedicated to studies and research on the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, affiliated with the Pereira Passos Institute (IPP) of the Rio de Janeiro City Hall.

Its objective is to disseminate technical and scientific production on topics related to the city of Rio de Janeiro, as well as its metropolitan connections and its role in regional, national, and international contexts. The collection is open to all researchers (whether municipal employees or not) and covers a wide range of fields — provided they partially or fully address the spatial scope of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Articles must also align with the Institute’s objectives, which are:

- to promote and coordinate public intervention in the city’s urban space;

- to provide and integrate the activities of the city’s geographic, cartographic, monographic, and statistical information systems;

- to support the establishment of basic guidelines for the city’s socioeconomic development.

Special emphasis will be given to the articulation of the articles with the city's economic development proposal. Thus, it is expected that the multidisciplinary articles submitted to the journal will address the urban development needs of Rio de Janeiro.

[1] Although the diagnosis of economic and social conditions focuses on the city of Rio de Janeiro, the proposed development strategy presented in this article considers the metropolitan region and its other areas of influence as integral components and potential territories for its implementation. It therefore stems from an urban-regional perspective.

[2] See Cano (2008) regarding the virtuous productive deconcentration that the country experienced in the 1970s, especially driven by investments under the Second National Development Plan (PND), and the spurious character of deconcentration during the post-1990 neoliberalization; and Diniz (1993), who addresses the trend of industrial reconcentration and the formation of a polygonal development, directed toward medium-sized cities located mainly in the interior of São Paulo, Paraná, Santa Catarina, and the Triângulo Mineiro.

[3] Based on the sum of unemployed, underemployed, discouraged, unavailable individuals, and those engaged in informal activities.

[4] The Planning Areas (AP) are territorial units established in Rio de Janeiro’s urban legislation, reaffirmed in Article 57 of Complementary Law No. 270/2024, the Master Plan for Sustainable Urban Development of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, as part of territorial planning and for the purpose of controlling urban development.

[5] At the time of writing this article, Complementary Law No. 286 was under review. As of September 8, 2025, it established the Southwest Zone of the City of Rio de Janeiro as a new geographic area, encompassing the neighborhoods of Administrative Regions XVI, XXXIV, and XXIV, which currently make up Planning Area 4, thereby officially detaching Barra da Tijuca and Jacarepaguá from the West Zone.

[6] It includes private, public, and mixed-capital companies while excluding jobs from the Direct Public Administration. This methodological choice is based on the fact that employment ties in the Direct Public Administration are linked to the address of their respective headquarters, even when the actual work takes place in another location. Such a criterion would compromise the reliability of the territorial analysis, giving disproportionate weight to AP 1 compared to the others.

[8] The Social Development Index (IDS) was inspired by the well-known Human Development Index (HDI), calculated by the UN/UNDP. Its purpose is to measure the degree of social development of a given geographic area in comparison with others, based on the results of the Population Census conducted by IBGE (Instituto Pereira Passos, 2024).

[9] In some texts, Karl Marx refers to structure, while in other instances the term infrastructure appears, as in the following quotation from Engels.

[10] The choice made for this propositional section of the article is to avoid reproducing already established and consolidated models, and instead to build upon the very diagnosis of the concrete reality under analysis, in a creative way and guided by the strategic development framework presented in the previous section.

[11] In this regard, see Boa Nova (2024b; 2025), which demonstrates how China’s economic and social development process in recent decades has largely been based on urban and transportation projects, standing as an example of a successful experience.