Volume 13 Issue 4 *Corresponding author felipeamaral@igeo.ufrj.br Submitted 22 Nov 2025 Accepted 13 Jan 2026 Published 05 Feb 2026 Citation AMARAL, F. G. et al. Urban green infrastructures in Rio de Janeiro: new perspectives from multisensor approaches and micro-scale analysis. Coleção Estudos Cariocas, v. 13, n. 4, 2026.

DOI: 10.71256/19847203.13.4.200.2025. The article was originally submitted in PORTUGUESE. Translations into other languages were reviewed and validated by the authors and the editorial team. Nevertheless, for the most accurate representation of the subject matter, readers are encouraged to consult the article in its original language.

| Urban green infrastructures in Rio de Janeiro: new perspectives from multisensor approaches and micro-scale analysis Sistemas verdes urbanos no Rio de Janeiro: novas perspectivas a partir de multissensores e análise em microescala Sistemas verdes urbanos en Río de Janeiro: nuevas perspectivas a partir de enfoques multisensor y análisis a microescala Felipe Gonçalves Amaral1, Evelyn de Castro Porto Costa2, Patricia Luana Costa Araújo3, Steffi Munique Damasceno dos Reis Vieira4, Amanda Lago de Souza Lugon5,

Mayara do Nascimento Ramos6, João Victor Ladeira Silva7,

João Victor da Silva dos Santos8, Rafael Ferreira Rodrigues Teixeira9,

Laura da Silva Bianchini10, Matheus Augusto de Souza11

e Carla Bernadete Madureira Cruz12 1 Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Athos da Silveira Ramos, 274, Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, CEP: 21941-916, ORCID: 0000-0003-0183-8430, felipeamaral@igeo.ufrj.br 2 Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), Rua Arízio Gomes da Costa, s/n - Jardim Flamboyant, Cabo Frio - RJ, ORCID 0000-0001-7648-6949, evelyncastroporto@gmail.com 3Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Athos da Silveira Ramos, 274, Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, CEP: 21941-916, ORCID: 0000-0002-0606-4887, patricialcaraujo@gmail.com 4Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Athos da Silveira Ramos, 274, Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, CEP: 21941-916, ORCID: 0000-0001-6493-3334, steffimunique@gmail.com 5Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Athos da Silveira Ramos, 274, Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, CEP: 21941-916, ORCID: 0009-0004-6735-664X, amanda.lagolugon@gmail.com 6Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Athos da Silveira Ramos, 274, Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, CEP: 21941-916, ORCID: 0009-0007-8445-9642, mayara.igeo@gmail.com 7Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Athos da Silveira Ramos, 274, Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, CEP: 21941-916, ORCID: 0000-0002-8293-9016, ladeiral.joao@gmail.com 8Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Athos da Silveira Ramos, 274, Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, CEP: 21941-916, ORCID: 0009-0004-7331-9175, joaovictor10632@gmail.com 9Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Athos da Silveira Ramos, 274, Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, CEP: 21941-916, ORCID: 0009-0006-0998-2145, rafafrteixeira@gmail.com 10Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Athos da Silveira Ramos, 274, Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, CEP: 21941-916, ORCID: 0009-0009-0112-9715, laurasbianchinigeo@gmail.com 11Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Athos da Silveira Ramos, 274, Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, CEP: 21941-916, ORCID: 0009-0009-9759-6691, mataugusto1999@gmail.com 12Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Athos da Silveira Ramos, 274, Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, CEP: 21941-916, ORCID: 0000-0002-3903-3147, carlamad@gmail.com

AbstractThis article examines the importance of high spatial resolution mapping in the assessment of Urban Green Infrastructures (UGI) in Rio de Janeiro, emphasizing the influence of scale on the identification and characterization of intra-urban vegetation. Studies based on coarser spatial resolutions tend to generalize and overlook relevant green fragments, such as street trees, small parks, and private gardens. In contrast, microscale approaches supported by very high spatial resolution data and multisensor techniques provide greater thematic detail and accuracy, enabling more precise diagnostics and supporting evidence-based urban planning actions and public policies. Keywords: urban green infrastructures, microscale, urban planning, remote sensing ResumoEste artigo analisa a importância dos mapeamentos de alta resolução espacial na avaliação dos Sistemas Verdes Urbanos (SVUs) no Rio de Janeiro, destacando a influência da escala na identificação e caracterização da vegetação intraurbana. Estudos baseados em resoluções espaciais mais grossas tendem a generalizar e ocultar fragmentos verdes relevantes, como arborização viária, pequenos parques e jardins privados. Em contraste, abordagens em microescala, apoiadas por dados de altíssima resolução e técnicas multissensores, permitem maior detalhamento e acurácia temática, contribuindo para diagnósticos mais precisos e para o embasamento de políticas públicas e ações de planejamento urbano. Palavras-chave: sistemas verdes urbanos, microescala, planejamento urbano, sensoriamento remoto. ResumenEste artículo analiza la importancia de los mapeos de alta resolución espacial en la evaluación de los Sistemas Verdes Urbanos (SVU) en la ciudad de Río de Janeiro, destacando la influencia de la escala en la identificación y caracterización de la vegetación intraurbana. Los estudios basados en resoluciones espaciales más gruesas tienden a generalizar e invisibilizar fragmentos verdes relevantes, como el arbolado urbano, pequeños parques y jardines privados. En contraste, los enfoques de microescala, apoyados en datos de muy alta resolución espacial y técnicas multiesensor, permiten mayor detalle y precisión temática, contribuyendo a diagnósticos más confiables y al apoyo de políticas públicas y planificación urbana. Palabras clave: sistemas verdes urbanos, microescala, planificación urbana, teledetección |

1 Urban green infrastructures and their spatial arrangement in the city of Rio de Janeiro

Cities are composed of several elements that, when articulated, confer specific forms, functions, and identities to urban landscapes. Among these elements, urban greenery stands out as an essential variable in the structure of cities around the world. According to Nucci (2001), green elements are extremely relevant and have become increasingly important in urban systems. As the only living infrastructure of the city, green spaces result from the interaction between natural and human factors (Douglas, 2012; Yang et al., 2014).

These spaces play a fundamental role in improving urban environmental conditions and in the ecological balance of territories (Chen; Lang; Li, 2019; Mabon; Shih, 2018). At the same time, they constitute important symbols of the urban environment, reflecting patterns of life, forms of spatial appropriation, and socio-spatial inequalities (Gómez et al., 2010; Kabisch; Qureshi; Haase, 2015; Theano; Tsitsoni, 2011).

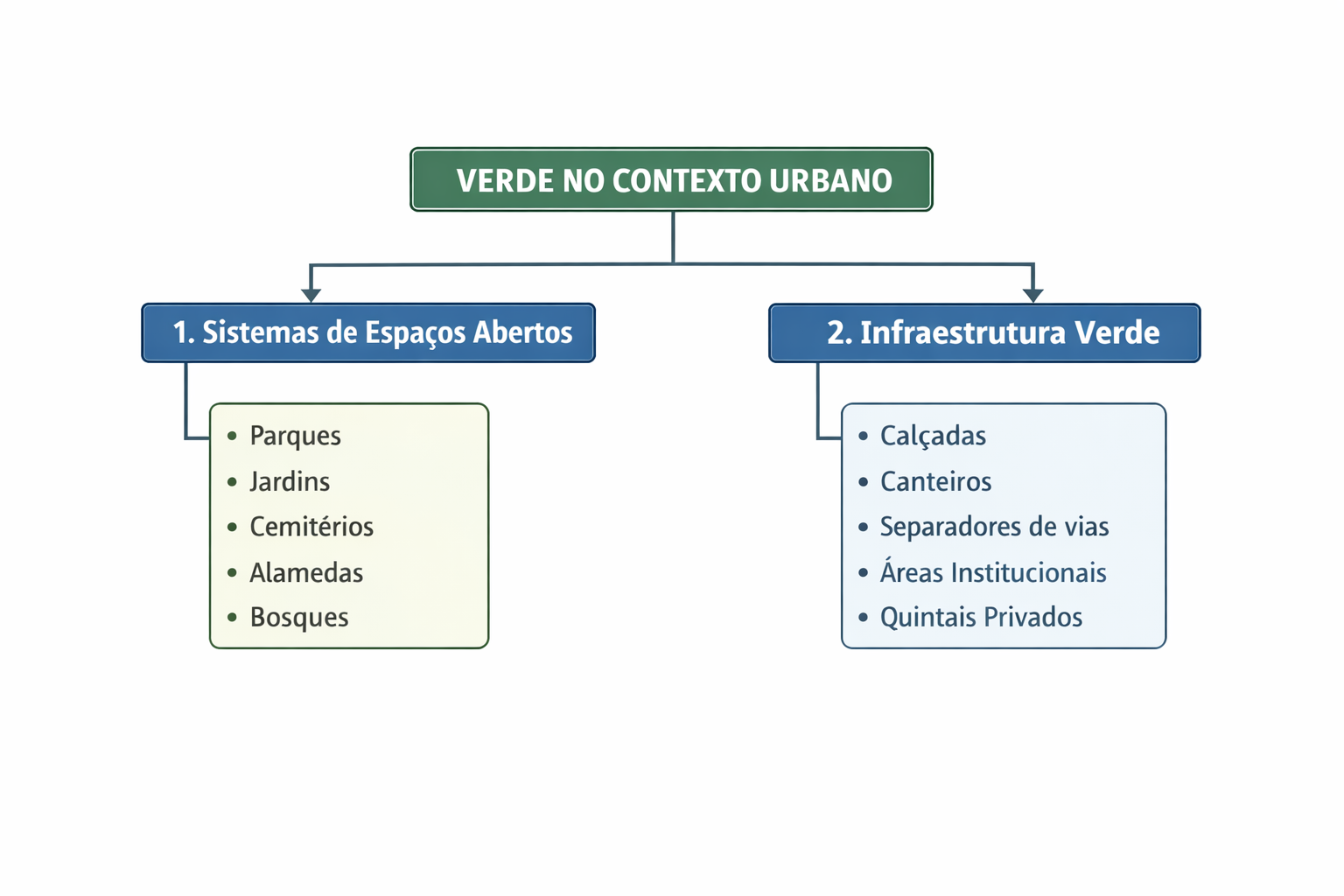

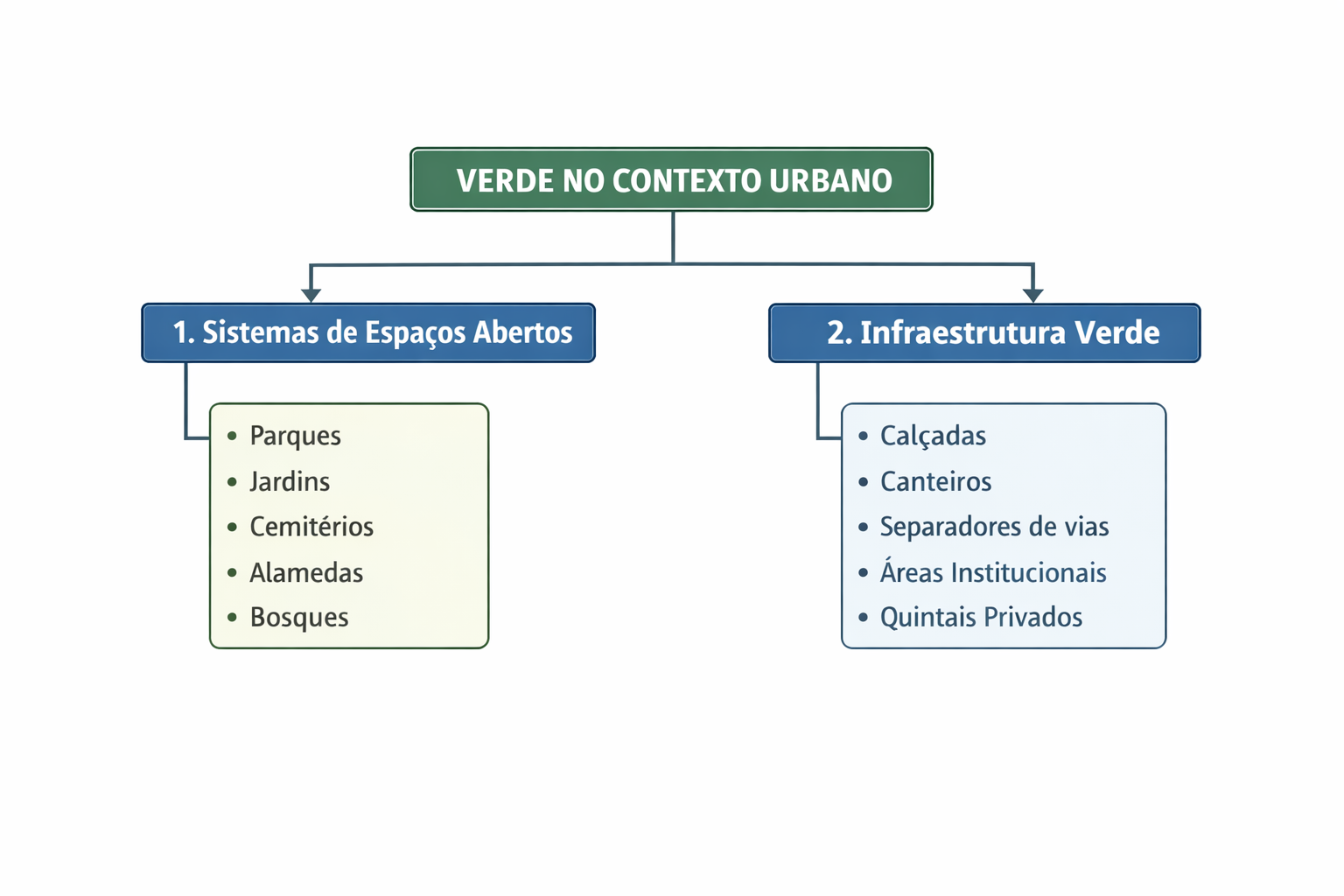

In the urban context, greenery generally manifests itself in two major modalities. The first refers to systems of open spaces, organized in patches of different sizes and with a predominance of vegetation. These are open spaces whose central element is greenery, serving ecological, aesthetic, and recreational purposes, such as parks, gardens, cemeteries, promenades, and woodlands (Cavalheiro et al., 1999; Nucci, 2001). The second modality refers to arboreal vegetation structures distributed throughout the urban fabric, such as street trees, medians, traffic separators, institutional areas, and private backyards. In highly anthropized environments, these trees contribute to stabilizing the microclimate, reducing atmospheric and noise pollution, enhancing the urban landscape, and promoting health and well-being, generating social, economic, and political benefits (Lima et al., 1994) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Organizational chart of Urban Green Infrastructures. On the left, naturalized green systems. On the right, fragmented intra-urban green infrastructures.

Source: Authors (2025)

In the urban context, green spaces assume diverse configurations that directly influence their ecological and social functions. As discussed in the literature, it is possible to distinguish formal green areas, which are planned and regulated, such as parks, squares, gardens, and urban woodlands (Cavalheiro et al., 1999; Nucci, 2001; Konijnendijk et al., 2006), and informal or spontaneous green areas, associated with vacant lots, slopes, riverbanks, and natural regeneration processes (Qureshi et al., 2010). In addition to these categories, privately vegetated spaces are included, such as residential backyards and private gardens, which, although fragmented and often overlooked in traditional planning, represent a significant share of the vegetation stock in densely built cities (Goddard; Benton; Dougill, 2010).

Urban Green Infrastructures (UGI) can be defined as a strategically planned network of natural and semi-natural areas within cities (Silveira et al, 2024; Cohen-Shacham et al., 2016). It is important to emphasize that the concept of nature as green infrastructure is not limited to green areas or open spaces; rather, it is a multifunctional approach that reconciles the conservation and protection of natural resources with urban development and the planning of human infrastructure (Madalena; Silva, 2021). This system, which promotes a connected network of spaces for urban activities and for human interaction with nature, is composed of large areas that anchor the system, corridors that connect ecosystems, and landscape fragments that may or may not be connected (Benedict; McMahon, 2006; Han; Keeffe, 2020; Harris et al., 2019).

The relevance of UGI has become central in contemporary debates on climate and biodiversity, especially in light of the growing responsibility of cities in efforts to mitigate and adapt to global climate change. Green spaces contribute to microclimate regulation by reducing temperatures through shading and evapotranspiration (Dobbs; Escobedo; Zipperer, 2011; Oke et al., 2017), in addition to reducing socio-environmental vulnerabilities by mitigating problems such as air pollution, flooding, and thermal stress (Akbari; Pomerantz; Taha, 2001; Bolund; Hunhammar, 1999; Luederitz et al., 2015; Locke; McPhearson, 2018). Thus, parks, squares, gardens, street trees, and privately vegetated areas are fundamental elements for the environmental and social balance of cities, directly influencing quality of life and debates on environmental justice (Herculano, 2008).

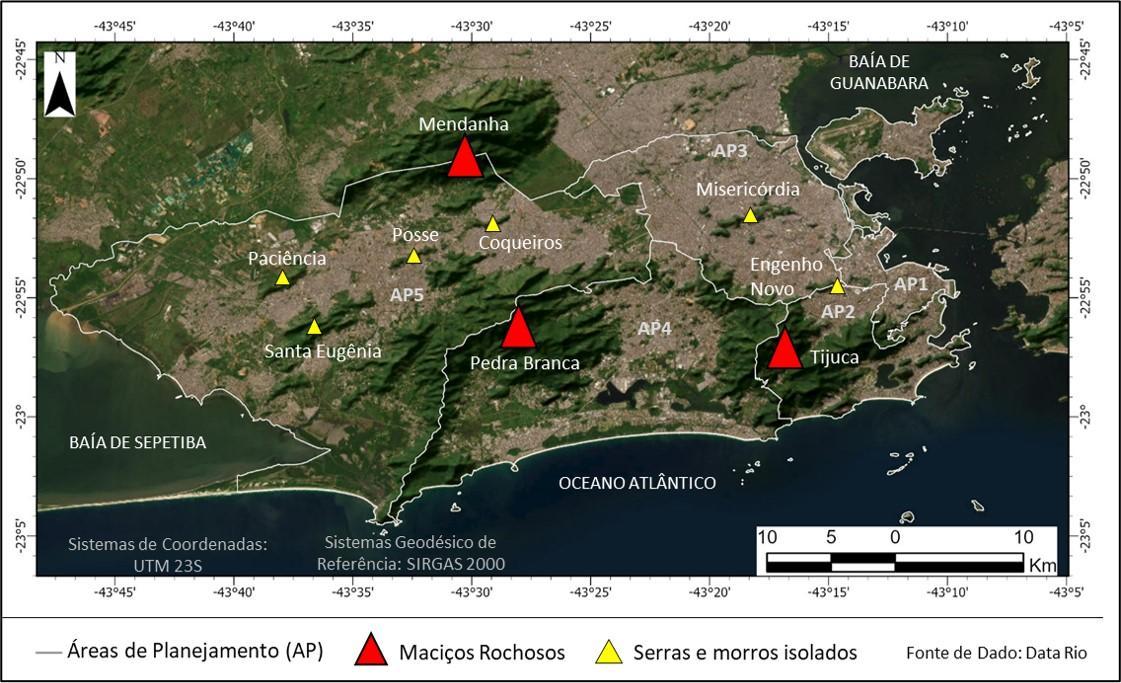

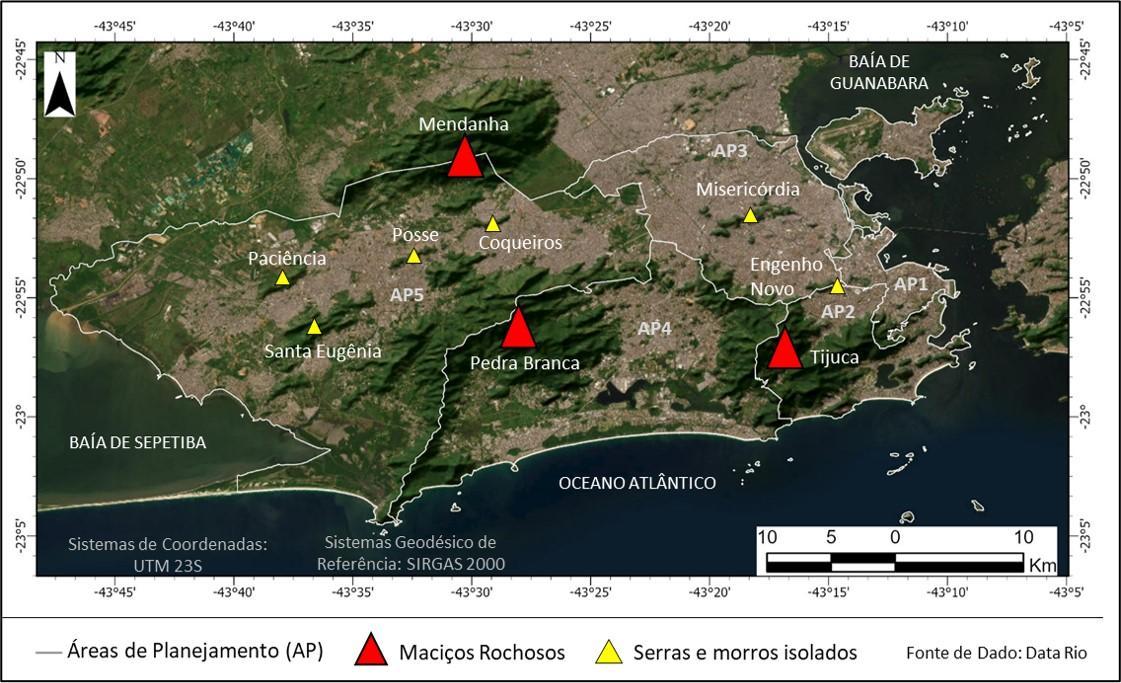

The city of Rio de Janeiro presents a unique physical-environmental configuration, resulting from the interaction between rugged relief, an extensive coastline, large forested massifs, and densely occupied urban areas. This territorial structure is organized around three major orographic complexes that shape the city’s landscape: the Tijuca Massif, the Pedra Branca Massif, and the Mendanha Range, where, respectively, Tijuca National Park, Pedra Branca State Park, and the Mendanha Municipal Natural Park are located (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Spatial arrangement of the large and small green massifs of the city of Rio de Janeiro

Source: Authors (2025)

In addition to these massifs, the city hosts smaller formations, often referred to as hills (morros), but which are configured as small mountain ranges, such as the Engenho Novo Range, located between Planning Areas (PAs) 2 and 3, and the Misericórdia Range, which has gained media attention due to issues related to public security. The six small mountain ranges that compose the orographic arrangement of the capital of Rio de Janeiro, unlike the large massifs, do not have robust environmental protection instruments. The lack of planning and specific legal measures makes these areas particularly vulnerable to disorderly urban expansion and to various degradation processes (Guia, 2013; Araújo et al., 2019).

The spatial arrangement of Urban Green Infrastructures (UGI) in Rio de Janeiro reveals a marked territorial asymmetry between regions with a high concentration of vegetation and densely urbanized areas, especially in the North Zone and the West Zone, where the presence of intra-urban greenery tends to be restricted to small fragments, squares, road medians, and private gardens. Within this configuration, the role played by different types of green spaces varies significantly across portions of the city. Large conservation units ensure the preservation of continuous urban forests and the provision of ecosystem services at the metropolitan scale, such as climate regulation and the protection of water resources. Small vegetated fragments and street trees, in turn, assume strategic importance at the local level, particularly in densely built areas, functioning as essential elements of connectivity and micro-environmental regulation (Figure 3).

Figura 3: Diversity of Urban Green Infrastructures in the City of Rio de Janeiro. (a) Vista Chinesa – Tijuca National Park; (b) Grajaú Street – North Zone; (c) Saens Peña Square – North Zone; (d) Francisco Campos Municipal School – North Zone.

Source: VisitRio, Authors, Ruas Cariocas, and Google Street View.

Figure 3a, corresponding to Vista Chinesa in Tijuca National Park, illustrates a large-scale naturalized green system whose function goes beyond recreation, contributing to microclimatic regulation, biodiversity conservation, and ecological connectivity. Figure 3b, on Grajaú Street, exemplifies street tree planting in a densely urbanized environment, highlighting the role of street trees in improving thermal comfort, air quality, and the humanization of urban landscapes. Figure 3c, referring to Saens Peña Square, represents a formal, organized, and planned green space inserted in an area of centrality, reinforcing the social and recreational function of these spaces in everyday urban life. Finally, Figure 3d, from the Francisco Campos Municipal School, highlights the presence of intra-block vegetation, which is important for increasing permeability, reducing heat islands, and diversifying green elements within the urban fabric. Taken together, the images illustrate the breadth and heterogeneity of UGI, showing how different forms of vegetation are integrated into urban space and perform distinct environmental, social, and landscape functions.

The response to seemingly simple questions, how much greenery exists in the city, where it is located, under what conditions it exists, and whether its distribution is equitable, depends on a central component: mapping and, inseparably, the scale of this mapping. Most diagnoses, zoning efforts, and impact analyses of vegetation in urban environments have focused on large parks or conservation units, using relatively broad spatial scales (Aram et al., 2019; Cao et al., 2010; Derkzen; Teeffelen; Verburg, 2015). Although relevant, this approach tends to generalize results, often rendering invisible local specificities present in small parks, squares, tree-lined sidewalks, private gardens, and dispersed vegetated fragments.

Traditionally, many urban studies are developed based on analyses conducted at broad spatial scales, suitable for assessing regional trends and monitoring large vegetation patches. While useful, these approaches present limitations when the goal is to understand processes that manifest at smaller geographic scales, such as the block, the street, or the lot, where the population’s everyday experience is expressed. In this sense, diagnostic approaches capable of more precisely representing the configuration and quality of intra-urban green areas become essential.

In the municipality of Rio de Janeiro, marked by strong diversity in forms of urbanization and by different institutional arrangements, the production of detailed and methodologically consistent analyses is fundamental to support public policies and guide management actions. The choice of analytical scale, therefore, ceases to be merely a cartographic decision and assumes a political character (Castro, 2014), in which very large geographic scales may reinforce invisibilities and inequalities, while approaches at smaller geographic scales allow the identification of deficits, vulnerabilities, and opportunities for intervention.

It is within this context that the concept of micro-scale stands out, here understood as the level of observation and representation (very small geographic scales and very large cartographic scales) that approaches the materiality of lived space, such as the block, the street, the lot, and the individual tree. At this scale, processes that are often hidden in more aggregated analyses become visible, such as the actual soil permeability of sidewalks, backyards, and small open spaces; the effective shading of streets, squares, and façades; the thermal impact of different arrangements of vegetation and surface materials; and the functional connectivity between small fragments, private gardens, and isolated trees.

Such diagnostics enable practical applications, such as accurate tree inventories, thermal comfort modeling, identification of priority areas for tree planting, planning of green corridors, and assessment of the contribution of private gardens to heat island mitigation. At the same time, they reinforce debates on environmental justice and urban microclimates by revealing inequalities in the distribution of the ecological benefits of greenery. Thus, the micro-scale is not merely a methodological alternative, but an analytical and political approach capable of bringing urban planning closer to the real living conditions in cities, enabling more precise, inclusive, and territorially grounded public decisions.

Accordingly, the objective of this article is to demonstrate the analytical and applied potential of using ultra-high spatial resolution data and multisensor approaches for micro-scale analysis of urban green infrastructures in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro, discussing how these diagnostics can support urban-environmental planning.

2 Resolution, scale, and multisensors: limits of “seeing” and new possibilities

As discussed previously, understanding urban green spaces based on reliable diagnoses requires mapping approaches capable of representing targets with an appropriate level of detail. This constitutes one of the main challenges: what is the appropriate scale? And which data should be used?

In this context, advances in geotechnologies, especially in the field of remote sensing, have profoundly transformed the way we observe, analyze, and interpret green infrastructures in urban space. Remote sensing refers to the set of sensors, equipment, and processing techniques used to understand phenomena based on the recording and analysis of interactions between electromagnetic radiation and the materials that compose the Earth’s surface (Novo, 2010). Data acquisition varies according to the level of observation and may be terrestrial, aerial (or suborbital), or orbital. Regarding the type of product generated, sensors can be classified as imaging or non-imaging. Imaging sensors produce records derived from the spectral response of the observed surface, resulting in images that can be interpreted and analyzed. Non-imaging sensors, in turn, do not generate images, but rather measurements or signals that describe spatial and geometric properties of the target.

Imaging sensors produce digital images composed of pixels. These images present characteristics associated with their different resolutions, which are also used in sensor classification. According to Novo (2011), spatial resolution is associated with pixel size and the ability to “see” details on the Earth’s surface; spectral resolution refers to the sensor’s ability to record energy responses across different wavelength intervals; radiometric resolution corresponds to the sensor system’s capacity to record reflectance or emittance values in different gray levels; while temporal resolution refers to the satellite revisit time (or that of a satellite constellation over the same location).

All image resolutions are important in studies that investigate the Earth’s surface. Among them, spatial resolution stands out because it is closely related to the scale of representation and the level of detail obtained in an image, allowing phenomena to be observed, measured, and understood at smaller geographic scales that demand greater detail. However, the ability to “see” space depends directly on the choices of analytical and representational scale, including the different spatial resolutions available from multiple sensors. These methodological decisions influence which elements become visible or invisible during the research process. Therefore, understanding the relationship between scale, resolution, and data selection is fundamental for producing accurate diagnoses aligned with the questions one seeks to answer.

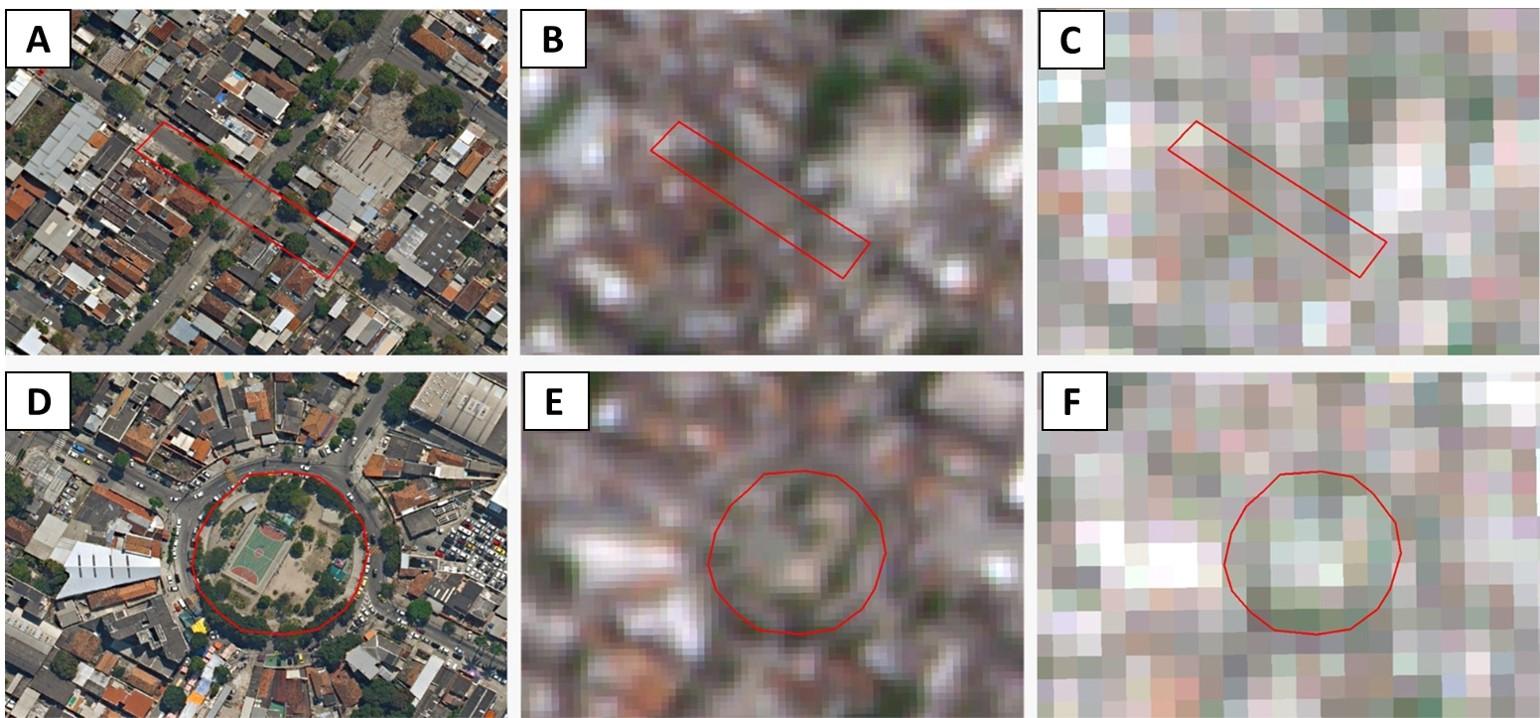

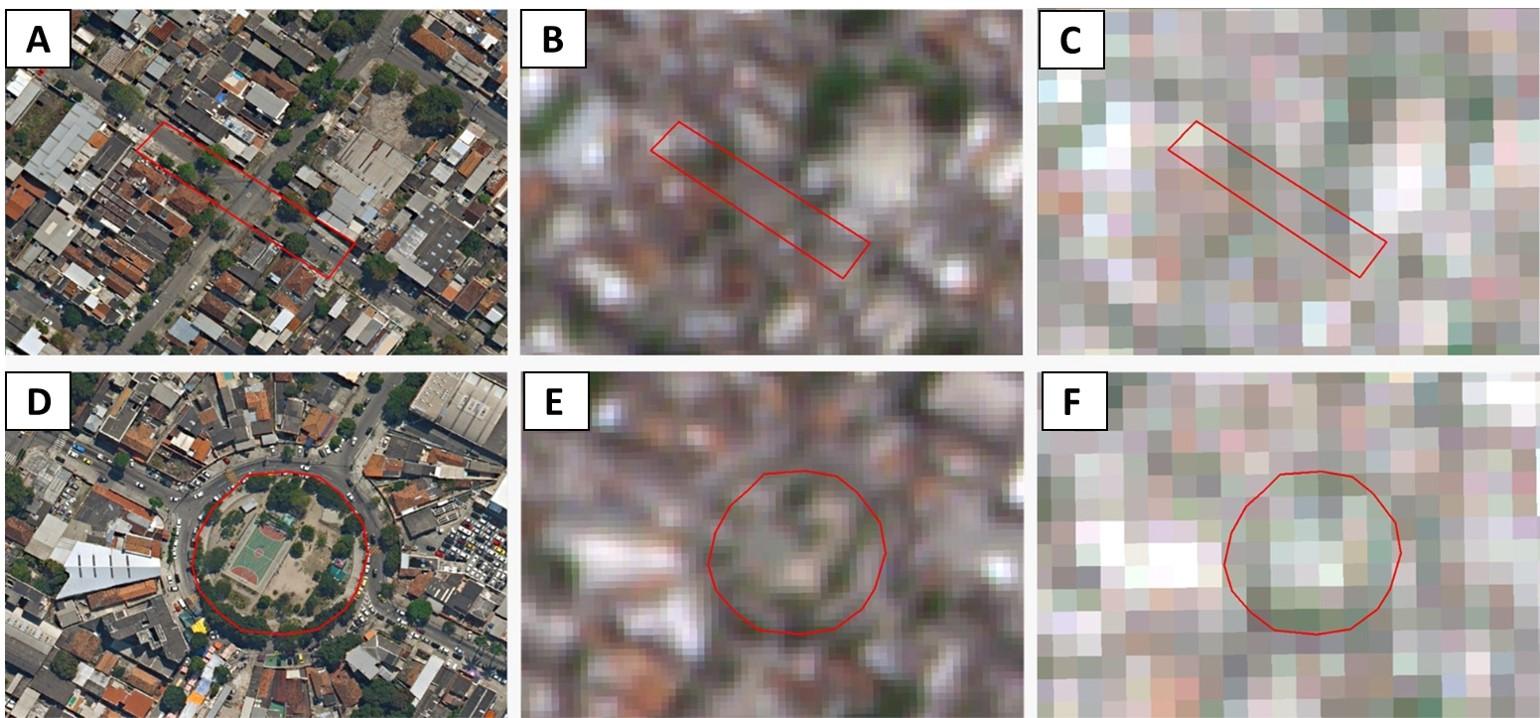

Figure 4 comparatively illustrates the effect of spatial resolution on the capacity to identify intra-urban green elements, demonstrating how crucial these choices are. The images show the same location observed at three different levels of detail: high resolution (pixel size of approximately 15 cm), intermediate resolution (pixel size of approximately 3 m), and medium resolution (pixel size of approximately 10 m). At high resolution, it is possible to clearly distinguish individual trees, canopies, flowerbeds, and small green areas embedded in the urban fabric, enabling precise analyses of distribution, connectivity, and ecological functionality at the street and block scale. As resolution decreases, these elements become progressively indistinct, resulting in spatial generalization and loss of information relevant to urban diagnostics. Small squares, street trees, and private gardens, clearly visible at submetric resolution, disappear as identifiable entities at intermediate resolution and are reduced to only a few pixels at 10 m resolution.

Figura 4: Changes in spatial resolution in the identification, delimitation, and classification of urban green infrastructures in the Penha Administrative Region: (a) and (d) orthophoto images (spatial resolution of 0.15 m); (b) and (e) Planet images (spatial resolution of 3.7 m); (c) and (f) Sentinel images (spatial resolution of 10 m).

Source: adapted from Teixeira (2025).

Figure 4 highlights how variation in spatial resolution directly influences the ability to detect, delimit, and classify Urban Green Infrastructures (UGI) in the Penha Administrative Region. As spatial resolution becomes coarser, there is a progressive loss of detail, reducing the accuracy of identifying smaller, fragmented vegetated elements embedded in denser urban fabrics. While very high-resolution images allow for more faithful recognition of forms, boundaries, and internal structures of UGI, medium- and low-resolution images tend to generalize patterns, simplify features, and sometimes aggregate different land cover types into a single class. This comparison underscores the importance of selecting a resolution appropriate to the mapping objective.

This argument becomes even more evident in Teixeira (2025), who demonstrates how changes in spatial resolution significantly alter the ability to identify, delimit, and classify different urban green infrastructures. Thus, resolutions of a few meters or submetric resolutions (below 1 m) become essential for the accurate representation of elements such as isolated trees, canopies, effective shading, and small green spaces embedded in the built fabric, features that remain invisible when analyzed using coarser resolutions.

In this sense, recognizing the characteristics of the data is decisive for producing more accurate diagnoses of intra-urban green cover. Spatial resolution ceases to be merely a technical attribute and becomes a strategic and political element in the formulation of research questions.

It is important to emphasize that the sensors presented belong to different categories and therefore generate different types of data, which implies distinct ways of defining spatial resolution. In imaging sensors, such as cameras mounted on drones or orbital optical sensors, spatial resolution is directly associated with pixel size on the ground, a concept widely discussed by Novo (2010). In non-imaging sensors, such as LiDAR, the level of detail is associated with point density obtained during scanning, usually measured in points per square meter. This understanding is well established in the classical literature on laser scanning, particularly in the works of Wehr and Lohr (1999) and Baltsavias (1999), which explain how the three-dimensional structure of point clouds depends directly on the spatial sampling rate of the sensor.

Thus, it is essential to emphasize that the products of these sensors are not ready-made images, but rather data structures that require additional processing steps to become spatial representations comparable to conventional images. This is the case of LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), whose measurements are originally provided as point clouds that must be classified, interpolated, and modeled to generate derived products such as Digital Elevation Models (DEM) or raster surfaces. Only after this conversion is it possible to associate them with a digital image that has a defined spatial resolution, that is, an associated pixel size.

Understanding the nature of the data produced by each sensor is therefore fundamental for correctly interpreting their products and representational capabilities. In recent decades, the development of orbital and airborne platforms has significantly expanded the range of available data. Very high-resolution imagery, aerophotogrammetric orthophotos, as well as LiDAR systems, drones, and mobile mapping technologies, now make it possible to achieve resolutions on the order of 10 to 20 cm, with high spectral, geometric, and altimetric detail. This level of precision enables applications such as identifying individual trees and their canopies; measuring effective shading at street level; differentiating vegetation typologies (arboreal, shrub, herbaceous); delimiting private gardens, flowerbeds, and urban interstices; and extracting three-dimensional information on vegetation and urban form. With ongoing technological advances, these analyses are becoming increasingly feasible.

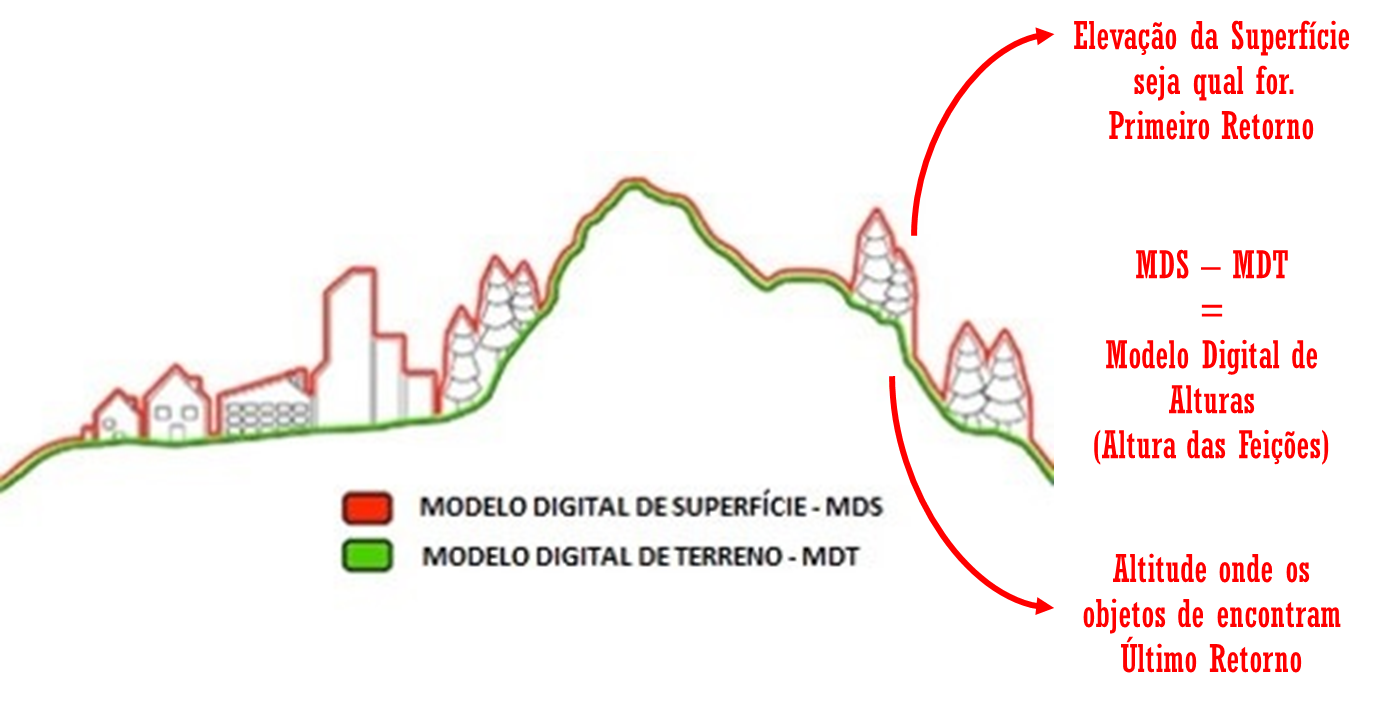

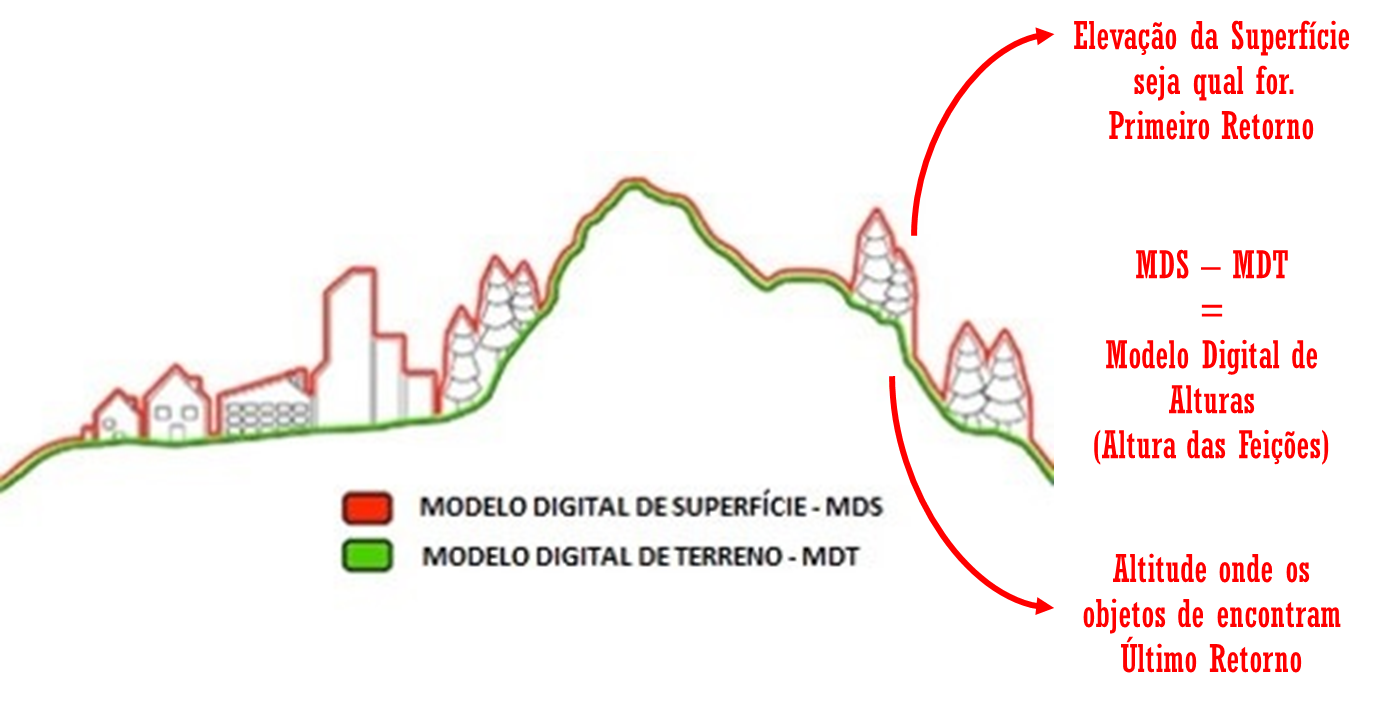

The use of LiDAR is a prominent example of this. This technology enables the acquisition of highly precise three-dimensional information about the Earth’s surface through the emission and return of laser pulses. From these returns, Digital Terrain Models (DTM) and Digital Surface Models (DSM) can be generated. Different classification, filtering, and interpolation methods may be employed in processing LiDAR data to produce these models. For example, generating a DTM from LiDAR data requires classifying points corresponding to objects above the ground in order to virtually remove them from the initial DSM (Pacheco et al., 2011).

Figure 5 illustrates the conceptual difference between DSM and DTM, highlighting their relevance for three-dimensional analyses in urban environments. The DSM represents surface elevation including all existing elements — buildings, trees, and other objects — generally corresponding to the first return captured by acquisition platforms. The DTM represents only the terrain, after filtering out these objects, reflecting the natural ground elevation. Subtracting the DTM from the DSM (DSM – DTM) yields the Digital Height Model, or in vegetation studies, the Canopy Height Model (CHM), which allows estimation of the actual height of features such as tree canopies. This product is fundamental for micro-scale applications, such as shading modeling, vegetation volume and biomass estimation, evaluation of vertical interactions between the built environment and arboreal structure, and analysis of green system stratification (trees, grass, shrubs, for example).

Figura 5: Figure 5: Digital Surface Model (DSM), Digital Terrain Model (DTM), and their difference, resulting in Digital Height Models in an urban environment.

Source: adapted from CPE Tecnologia.

Thus, integrating different data sources, known as a multisensor approach, has proven to be a strategic pathway for minimizing uncertainties and expanding analytical possibilities. Combining optical, three-dimensional, and thermal data allows for modeling shading at different times of day, estimating vegetation vertical structure, assessing urban heat island formation, and calculating attributes such as canopy height, biomass, permeability, and ecological connectivity. Although this approach requires methodological rigor, planning, and continuous validation, it significantly expands the interpretive potential of remote sensing products.

In summary, there is no universally ideal sensor. The choice of the most appropriate data depends on the size of the target, the objective of the study, and the type of decision to be supported. For micro-scale diagnostics, very high spatial resolution data and multisensor approaches become privileged tools, capable of bringing maps closer to the everyday reality experienced in the streets, squares, and backyards of the city.

It is important to recognize, however, that access to very high spatial resolution data is still not democratized. High costs, temporal limitations, and institutional barriers restrict their systematic use, especially in municipalities with fewer technical and financial resources. This reinforces the need for public policies that treat spatial data as essential infrastructure for urban planning and management.

3 The greenery of Rio de Janeiro and the importance of the microscale

The production of detailed mappings of urban vegetation in Rio de Janeiro is extremely necessary, mainly focusing on the analytical potential of the data available in the capital of the state of Rio de Janeiro. The possibility of multisensor analysis becomes feasible and multifaceted in the municipality, given the extensive temporal archive of orthophotos available, which evolved into false-color orthophotos with the presence of near-infrared (NIR) in the most recent flights (2019 and 2024), in addition to data derived from LiDAR point clouds, such as DSMs and DTMs.

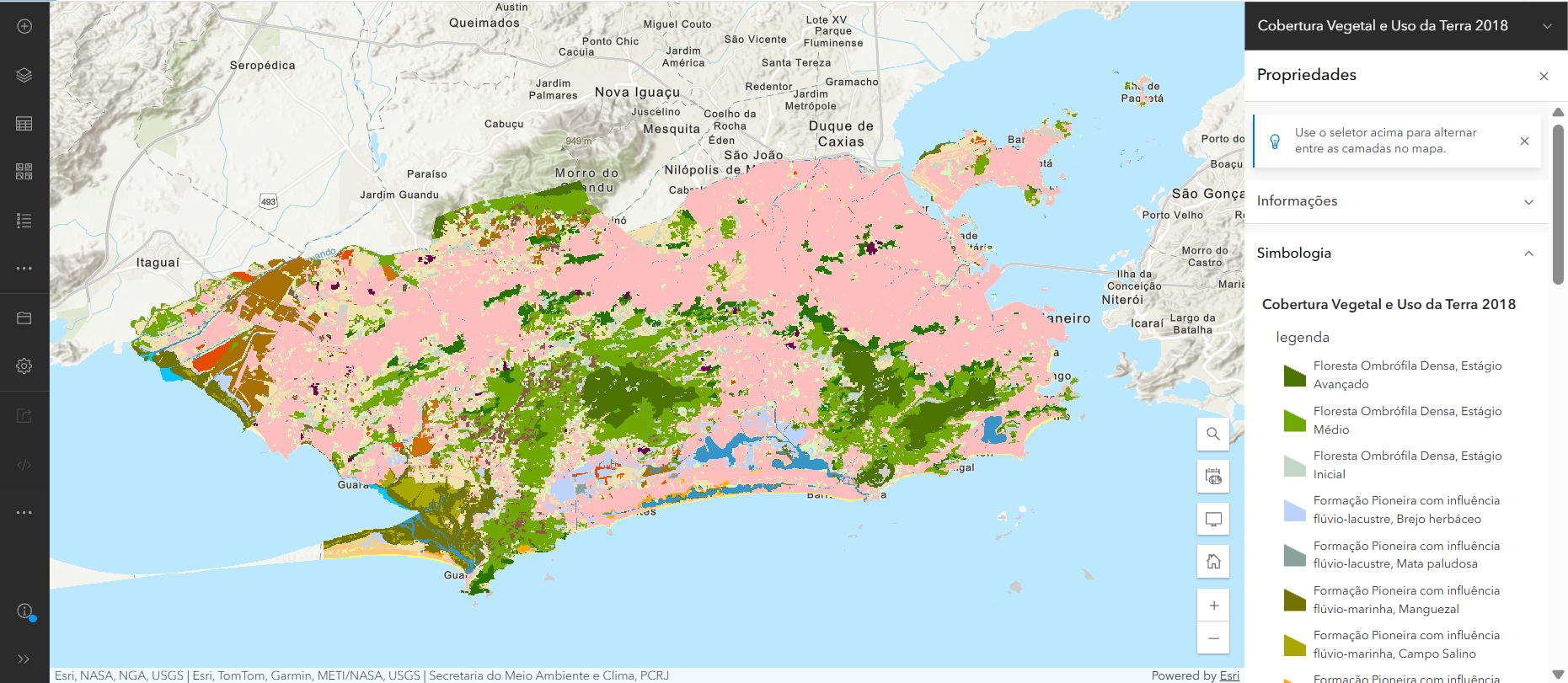

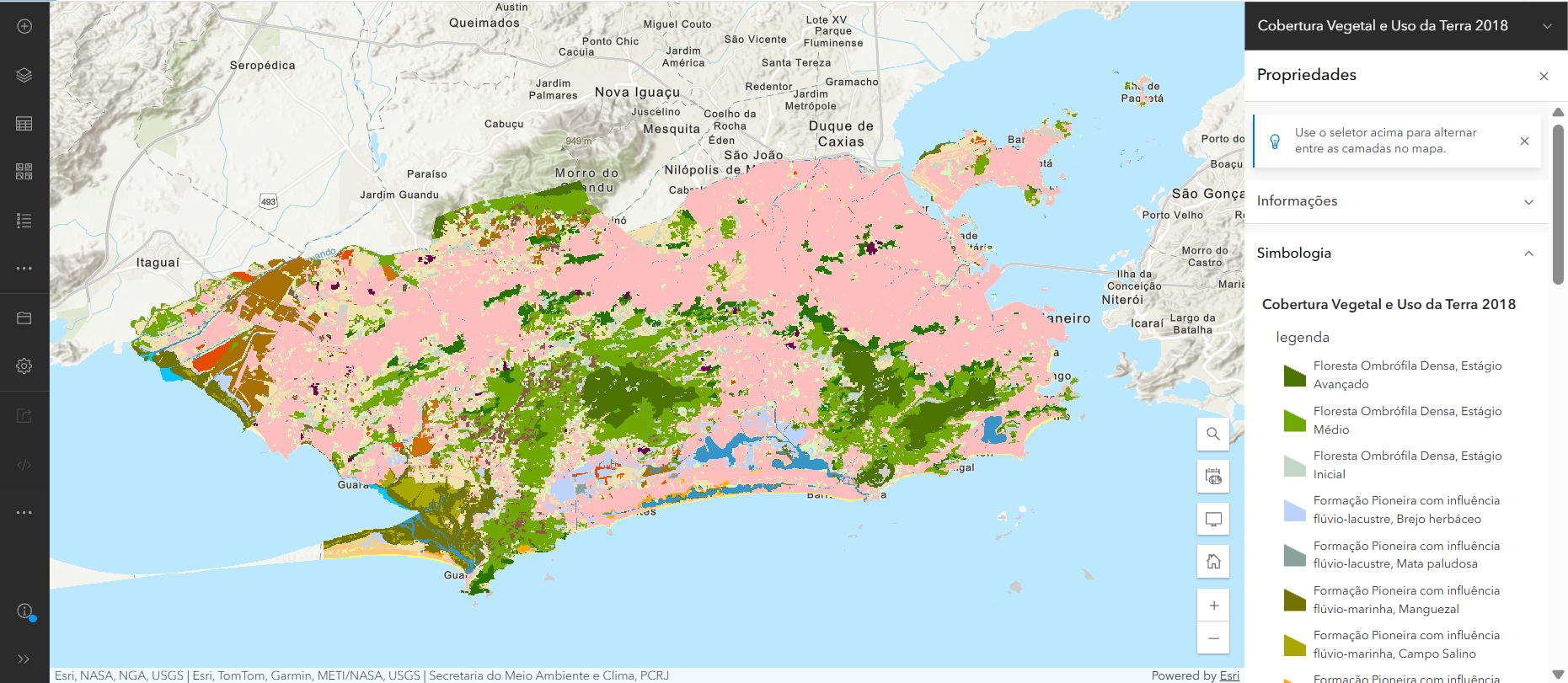

It is noteworthy that the City Hall of Rio de Janeiro has, in its database, a land cover and land use map for the year 2018, in which a comprehensive and well-detailed legend can be observed (DATA.RIO, 2025). However, from a visual analysis, it is possible to observe that the vegetation cover mapping focuses on the largest forest massifs of the city and manages to detail some areas of smaller massifs, while still not allowing the identification of intra-urban vegetation and its detailing at the microscale (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Land Cover and Land Use of the city of Rio de Janeiro, 2018.

Source: Data.Rio

It can be observed that, given the demand for more detailed data and the diversity of available imagery, some recent studies have relied on very high spatial resolution images and/or multisensor methodologies. The studies by Ruffato-Ferreira (2016), Amaral et al., (2022), Ramos et al. (2023), Silveira et al. (2024), and Lugon et al. (2025) present preliminary results that demonstrate more precise diagnostics, which can support urban and environmental planning strategies aligned with contemporary climatic and socio-spatial challenges.

The dissertation by Ruffato-Ferreira (2016) highlights the relevance of private green areas, especially those present in domestic backyards, as a strategic component for urban sustainability in the suburbs of Rio de Janeiro. The author quantifies and analyzes the contribution of these areas to the urban greenery of AP3 (Planning Area 3 of the municipality of Rio de Janeiro), using a GEOBIA approach (Geographic Object-Based Image Analysis), combined with data mining applied to high-resolution images. The GEOBIA approach adopts the concept of the object as the basis of the semantic information necessary for image interpretation, rather than the pixel (Trimble, 2014), grouping similar pixels at the level of geographic objects.

The results of Ruffato-Ferreira (2016) demonstrate that vegetated backyards represent 40% of the green area officially mapped by the municipality, corresponding to 13.87% of the residential area and 5.59% of the total urban area, revealing their significant role in mitigating socio-environmental problems, including heat islands, air pollution, and the scarcity of green spaces.

Another example is the study by Amaral et al. (2022), which used WorldView-2 images (2 m) and object-oriented classification (GEOBIA) to identify and characterize intra-urban green areas in AP3, a region that covers a large portion of the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro. The study identified that 34% of the total area of AP3 corresponds to green areas, unevenly distributed, with high concentrations on Ilha do Governador, Serra da Misericórdia, and near forest massifs. Densely urbanized areas, such as Complexo da Maré and Pavuna, show a strong scarcity of vegetation, highlighting the existence of green gaps associated with socioeconomic vulnerability.

The data from Amaral et al. (2022) gave rise to the recent research by Silveira et al. (2024), which deepens the discussion on the contribution of private gardens and privately owned vegetated spaces to urban thermal comfort. The authors demonstrate that gardens with a higher proportion of arboreal vegetation and better spatial connectivity present lower surface temperatures, reinforcing the importance of considering private green areas as strategic infrastructure for climate mitigation, an element often absent in traditional mappings.

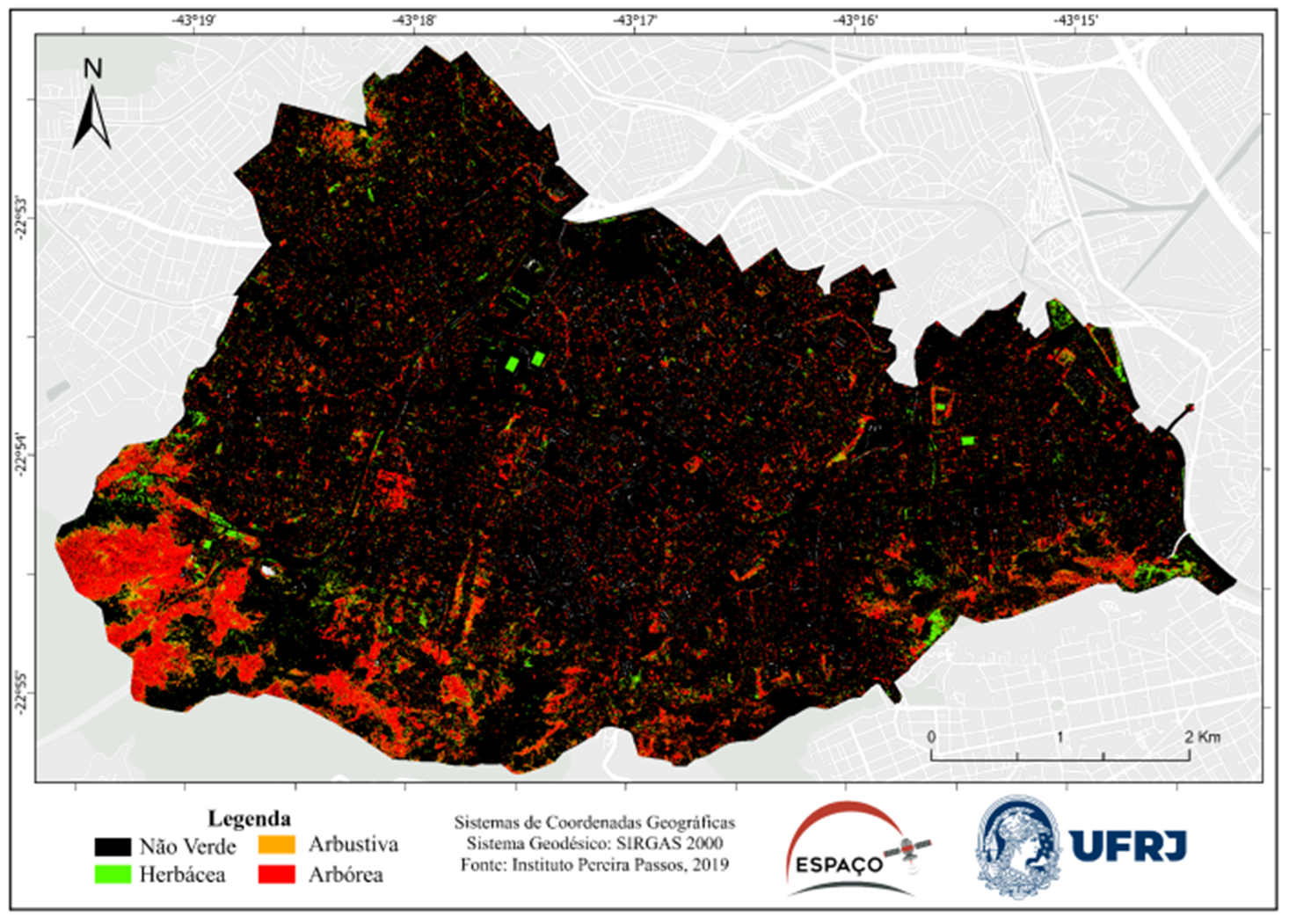

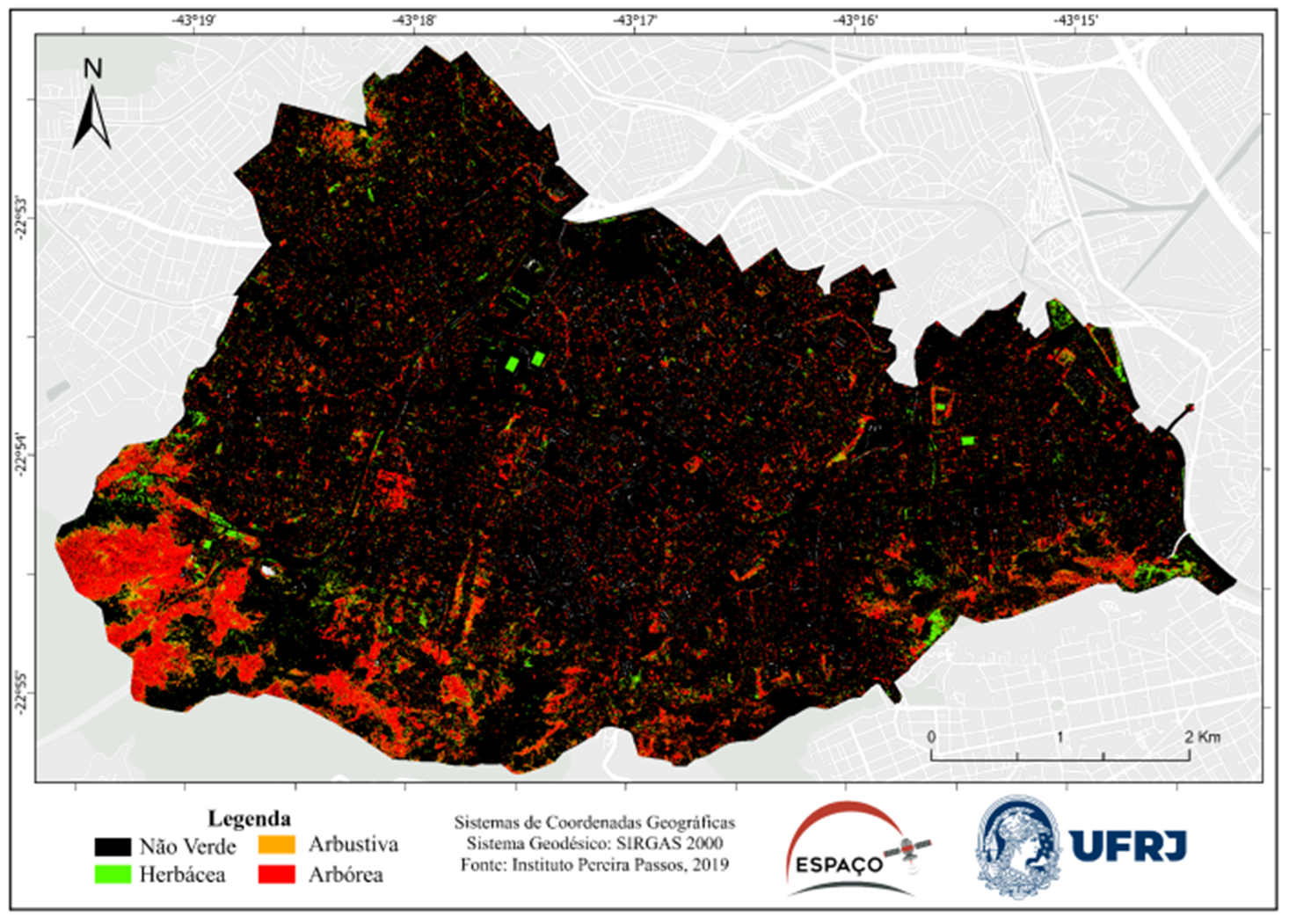

Another important advance observed is the mapping model developed by Ramos et al. (2023), which used a 15 cm orthophotomosaic and LiDAR data from 2019 for the Administrative Region of Méier, allowing the identification of vegetation typologies with a high level of detail. The GEOBIA approach made it possible to distinguish arboreal vegetation (64.9%), shrub vegetation (20.04%), and herbaceous vegetation (14.95%), achieving an accuracy of 96% and a Kappa coefficient of 0.91. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of multisensor approaches for the production of advanced tree inventories and microscale diagnostics that can be replicated in other urban areas (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Preliminary mapping resulting from the model for mapping urban green infrastructures of the Administrative Region of Méier by height stratification.

Source: adapted from Ramos et al. (2023).

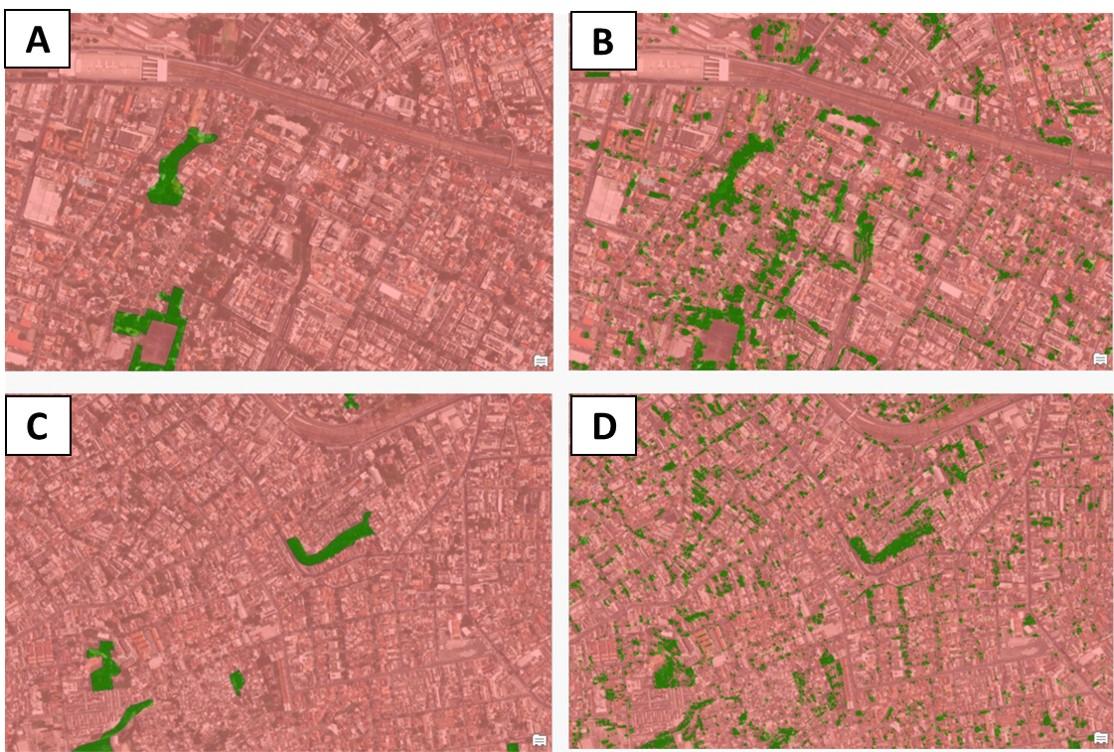

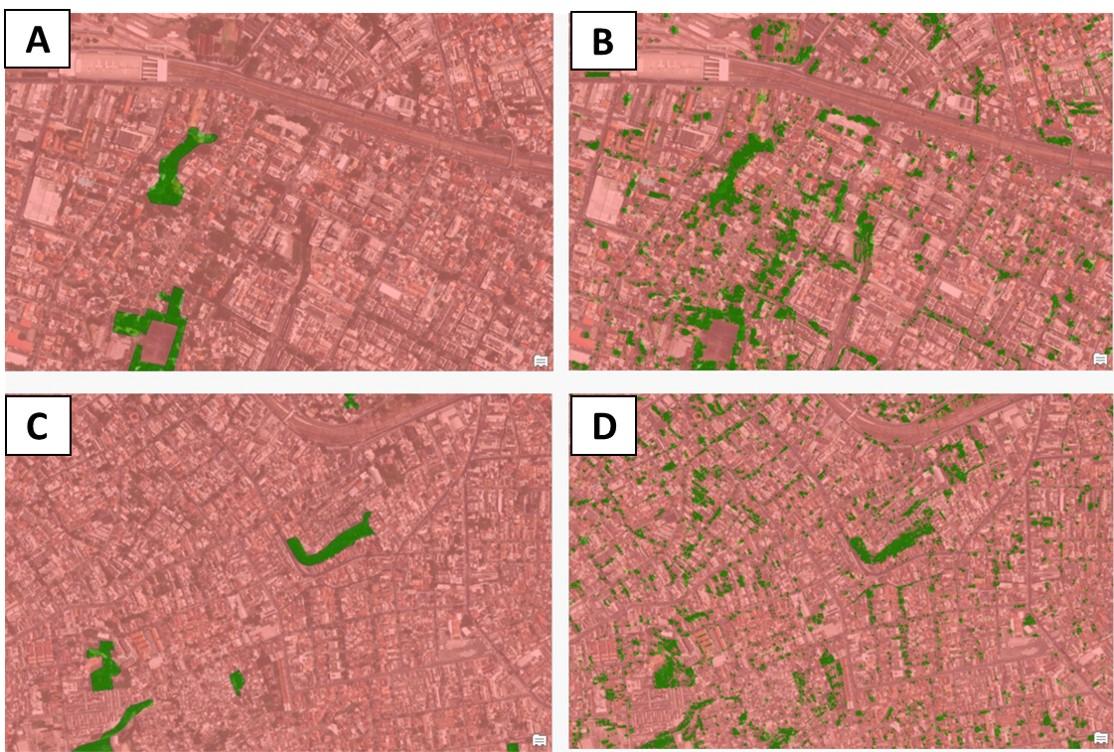

Based on the results of this latest research, carried out with data from 2019, it is possible to compare them with the municipal vegetation cover data from 2018. Figure 8 presents this direct comparison between green area mapping results. It can be observed that, in images with lower-scale mapping, only large vegetated patches are identified and represented on the map (in green), while most vegetation distributed in small fragments, such as isolated trees, street trees, and private gardens, remains absent. In contrast, in higher-scale mapping images, the spatial representation becomes much more detailed, revealing a significantly greater number of pixels classified as vegetation. This analysis highlights how detailed intra-urban mapping gives visibility to green fragments that change the perspective of urban management and planning at a time of climate emergency, in which adaptation and mitigation are also local issues.

Figure 8: Comparison between mapping (a) and (c): Land Cover and Land Use of the City Hall of Rio de Janeiro (2018), and mapping (b) and (d): green areas of 2019 carried out by Ramos et al. (2023).

Source: adapted from Ramos et al. (2023).

Figure 8 presents a comparison between two cartographic products produced at different times. Figures 8a and 8c correspond to the land cover mapping prepared by the City Hall of Rio de Janeiro in 2018, while Figures 8b and 8d show the preliminary map by Ramos et al. (2023). The upper images (Figures 8a and 8b) refer to the neighborhoods of Engenho de Dentro and Todos os Santos, while the lower images (Figures 8c and 8d) depict the neighborhoods of Engenho Novo and Lins de Vasconcelos. This composition highlights methodological and interpretative differences between the two surveys, allowing observation of how data updating and refinement of geospatial categories can modify the representation of territorial elements and the understanding of the urban configuration of these areas.

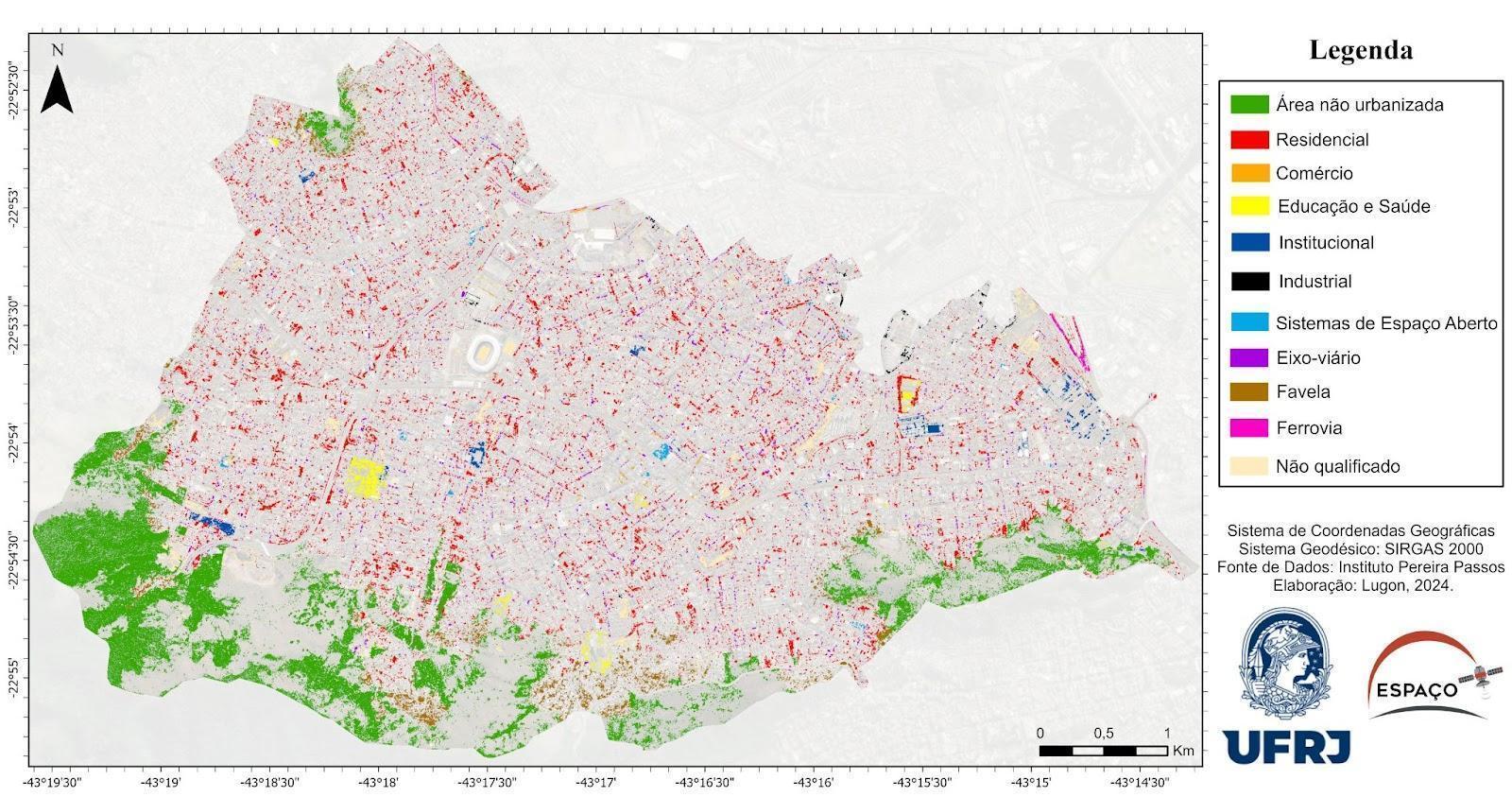

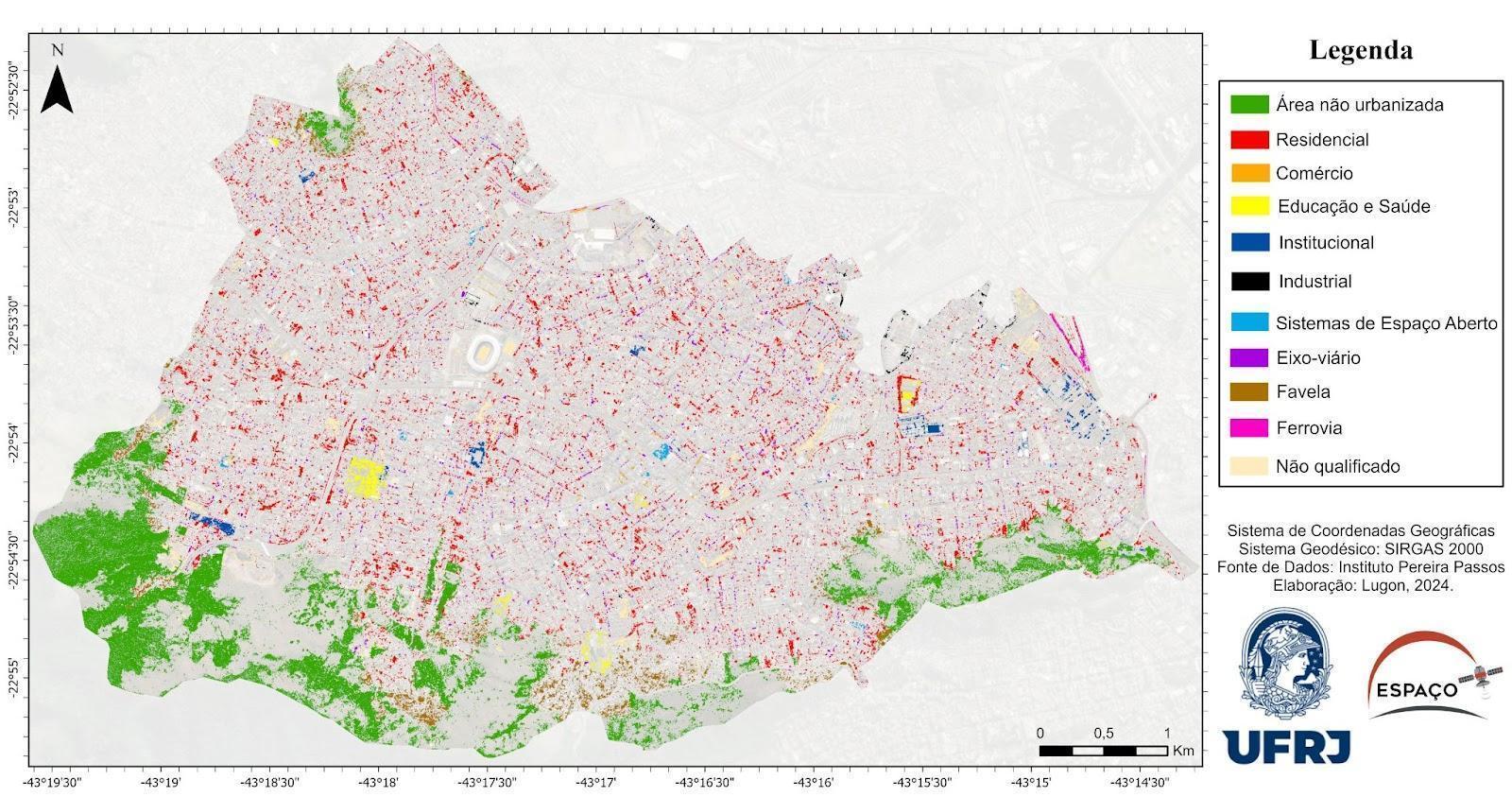

The change in the level of detail enables new analyses, as shown by Lugon et al. (2025), in which the authors propose a methodology for mapping and qualifying intra-urban vegetation based on the articulation between very high spatial resolution data derived from Ramos et al. (2023) and urban morphology information (Figure 9).

The research identifies and analyzes the distribution of different vegetation typologies in distinct spatial contexts, such as road axes, residential areas, railways, open spaces, and favelas, demonstrating that 68.99% of the vegetation is arboreal, with strong predominance along the road structure, while herbaceous-shrub vegetation is concentrated in more physically restricted areas, such as railways. The results highlight the importance of microscale diagnostics to guide public policies, define afforestation priorities, and support urban-environmental planning actions.

Figure 9: Map of qualification of urban green infrastructures by urban situation.

Source: Lugon et al., (2025).

4 Final considerations

In general, these studies show that the production of detailed diagnostics on urban vegetation depends on microscale mapping and that, today, in the city of Rio de Janeiro, this is possible due to the combination of high spatial resolution, multisensor approaches, and integration with socio-spatial data, allowing analyses that are more equitable and more closely aligned with territorial reality. It is evident that the studies demonstrate that the methodological framework is still under construction and that the coverage of the mappings remains a challenge. It can be concluded that there have been many advances and that greater levels of detail have been achieved through the large volume of available data. However, there are still many challenges, such as the effort required for editing mappings and adapting data.

Beyond the general mapping of urban vegetation, the microscale has proven to be a powerful instrument for understanding micro-level problems that directly influence environmental quality and the daily life of the population of Rio de Janeiro. These products enable applied analyses with direct potential for public policies and localized interventions. The availability of very high spatial resolution data and multisensor approaches not only refines answers to traditional questions such as “how much green space exists?”, but also allows the formulation of new questions that were previously impossible or impractical: How can the real thermal mitigation capacity be estimated per tree, street, or block? How can water deficit and real infiltration capacity be characterized on sidewalks and urban soils? How can priority areas for tree planting be identified based on health and socio-environmental vulnerability indicators? How can the risk of tree falls be mapped based on 3D structure and wind dynamics? How can private gardens and spontaneous vegetated areas be integrated into urban planning as functional green infrastructure? These questions reflect a paradigm shift: from measuring coverage to the functional qualification of urban vegetation.

Detailed microscale diagnostics open new opportunities for evidence-based urban governance. In the case of Rio de Janeiro, an emblematic example is the Continuous Vegetation Cover Monitoring Program (PMCV), institutionalized by Decree No. 54,071/2024, which consolidates one of the longest urban monitoring time series in Latin America and integrates high spatial resolution data, inventories, and field validation. This series of products, dating back to 1984, has evolved toward increasingly detailed mapping scales. The urban green mapping for the year 2018, previously presented, can be further refined and open new ways of understanding urban greenery.

The integration between microscale analyses and urban policies makes it possible to transform data into concrete decisions, ensuring greater transparency, efficiency, and territorial justice. In this sense, the diagnostics presented throughout this section reinforce that contemporary urban planning needs to abandon generalized approaches and adopt methodologies that are sensitive to intra-urban differences, bringing public policy design closer to the real experience of the lived territory.

References

AKBARI, H.; POMERANTZ, M.; TAHA, H. Cool Surfaces and Shade Trees to Reduce Energy Use and Improve Air Quality in Urban Areas. Solar Energy, v. 70, n. 3, 2001. DOI: 10.1016/S0038-092X(00)00089-X

AMARAL, F. G. et al. O verde intraurbano da área de planejamento 3 carioca: mapeamento e padrões espaciais com apoio das geotecnologias. In: Elizabeth Maria Feitosa Da Rocha De Souza. (Org.). Geoinformação e Análise Espacial: Métodos Aplicados A Áreas Antropizadas. Rio De Janeiro: Appris, 2022.

ARAM, F. et al. Urban Green Space Cooling Effect in Cities. Helyon, v. 5, n. 4, 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01339

ARAUJO, P. L. C. et al. A Serra da Misericórdia, o Maciço esquecido do Rio De Janeiro, como objeto do Planejamento Urbano-Ambiental. In: Encontro da ANPEGE, São Paulo. Anais do XIII ENANPEGE. São Paulo: 2019.

BALTSAVIAS, E. P. Airborne laser scanning: basic relations and formulas. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, v. 54, n. 2-3, 1999.

BENEDICT, M. A.; MCMAHON, E. T. Green Infrastructure: linking landscapes and communities. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2006.

BOLUND, P.; HUNHAMMAR, S. Ecosystem Services in Urban Areas. Ecological Economics, v. 29, no. 2, 1999. DOI: 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00013-0

CAO, X. et al. Quantifying the Cool Island Intensity of Urban Parks Using ASTER and IKONOS Data. Landscape and Urban Planning, v. 96, n. 4, 2010. DOI: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.03.008

CASTRO, I. E. Escala e pesquisa na geografia. Problema ou solução?. Espaço Aberto, v. 4, n. 1, 2014. DOI: 10.36403/espacoaberto.2014.2435

CAVALHEIRO, F. et al. Proposição de terminologia para o verde urbano. Boletim Informativo da Sociedade Brasileira de Arborização Urbana, Rio de Janeiro, v. XVII, n. 3, 1999.

CHEN, T.; LANG, W.; LI, X. Exploring the impact of urban green space on residents’ health in Guangzhou, China. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, v. 146, n. 1, 2019. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000541

COHEN-SHACHAM, E. et al. (Org.). Nature-based solutions to address global societal challenges. Gland : IUCN, 2016.

DATA.RIO. Cobertura Vegetal e Uso da Terra 2018. DATA.RIO. Rio de Janeiro, 2018. Available at: https://www.data.rio/datasets/PCRJ::cobertura-vegetal-e-uso-da-terra-2018/about. Accessed on: 20 nov. 2025.

DERKZEN, M. L.; TEEFFELEN, A. J. A. V.; VERBURG, P. H. REVIEW: Quantifying Urban Ecosystem Services Based on High-resolution Data of Urban Green Space: an Assessment for Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Journal of Applied Ecology, v. 52, n. 4, 2015. DOI: 10.1111/1365-2664.12469

DOBBS, C.; ESCOBEDO, F. J.; ZIPPERER, W. C. A Framework for Developing Urban Forest Ecosystem Services and Goods Indicators. Landscape and Urban Planning, v. 99, n. 3-4, 2011. DOI: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.11.004

DOUGLAS, I. Urban ecology and urban ecosystems: understanding the links to human health and well-being. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, v. 4, n. 4, 2012. DOI: 10.1016/j.cosust.2012.07.005

GODDARD, M. A.; BENTON, T. G.; DOUGILL, A. J. Beyond the garden fence: landscape ecology of cities. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, v. 25, n. 4, 2010. DOI: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.12.007

GÓMEZ, F. et al. Green areas, the most significant indicator of the sustainability of cities: Research on their utility for urban planning. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, v. 137, n. 3, 2011.

GUIA, E. V. F. Relações entre processo de ocupação e as características socioambientais da região da Serra da Misericórdia, subúrbio do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Geografia) - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2013.

HAN, Q.; KEEFFE, G. Stepping-Stone City: Process-Oriented Infrastructures to Aid Forest Migration in a Changing Climate. In: ROGGEMA, R. (Org.). Nature Driven Urbanism. Springer, Cham, 2020. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-26717-9_4

HARRIS, M. et al. Urbanisation of Protected Areas within the European Union — An Analysis of UNESCO Biospheres and the Need for New Strategies. Sustainability, v. 11, n. 21, 2019. DOI: 10.3390/su11215899

HERCULANO, S. O clamor por justiça ambiental e contra o racismo ambiental. InterfacEHS: Revista de gestão integrada em saúde do trabalho e meio ambiente, v. 3, n. 1, 2008.

KABISCH, N.; QURESHI, S.; HAASE, D. Human–environment interactions in urban green spaces — A systematic review of contemporary issues and prospects for future research. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, v. 50, [S.n.], 2015. DOI: 10.1016/j.eiar.2014.08.007

KONIJNENDIJK, C. et al. Defining urban forestry – A comparative perspective of North America and Europe. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, v. 4, n. 3-4, 2006. DOI: 10.1016/j.ufug.2005.11.003

LIMA, A. M. L. P. et al. Problemas de utilização na conceituação de termos como espaços livres, áreas verdes e correlatos. In: Anais... São Luís: Uema/Emater-Ma, 1994.

LOCKE, D. H.; MCPHEARSON, T. Urban areas do provide ecosystem services. Frontiers in Ecology & the Environment, v. 16, n. 4, 2018. DOI: 10.1002/fee.1796

LUEDERITZ, C. et al. A Review of Urban Ecosystem Services: Six Key Challenges for Future Research. Ecosystem Services, v. 14, [S.n.], 2015. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.05.001.

LUGON, A. L. S. et al. Qualificação das Tipologias do Verde Intraurbano de Acordo com a situação geográfica na Região Administrativa Méier (Rio de Janeiro). In: Anais do XXI Simpósio Brasileiro de Sensoriamento Remoto, 2025, Salvador. Anais eletrônicos..., Galoá, 2025.

MABON, L.; SHIH, W. What might ‘just green enough’ urban development mean in the context of climate change adaptation? The case of urban greenspace planning in Taipei Metropolis, Taiwan. World development, v. 107, [S.n.], 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.035

MADALENA, M.A.; SILVA, A.S. Infraestrutura Verde: uma abordagem sistêmica de integração urbano-rural. Cadernos Proarq, v. 1, n. 37, 2021. DOI: 10.37180/2675-0392-n37v1-8

NOVO, E. M. L. M. Sensoriamento Remoto: Princípios e Aplicações. ed.4. São Paulo: Blucher, 2010.

NUCCI, J. C. Qualidade Ambiental e Adensamento Urbano: um estudo da ecologia e do planejamento urbano aplicado ao distrito de Santa Cecília. São Paulo: Fapesp, 2001.

OKE, T. R. et al. Urban Climates. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

PACHECO, A. P. et al. Classificação de pontos LIDAR para a geração do MDT. Boletim de Ciências Geodésicas, v. 17, n. 3, p. 471–438, jul. 2011. DOI: 10.1590/S1982-21702011000300006

QURESHI, S.; BREUSTE, J. H.; LINDLEY, S. J. Green Space Functionality Along an Urban Gradient in Karachi, Pakistan: A Socio-Ecological Study. Human Ecology, v. 38, n. 2, 2010. DOI: 10.1007/s10745-010-9303-9

RAMOS, M. N. et al. Modelagem de áreas de cobertura vegetal intraurbanas: uma proposta metodológica com base em multisensores. In: Anais do XX Simpósio Brasileiro de Sensoriamento Remoto, 2023, Florianópolis. Anais eletrônicos..., INPE, 2023.

RIO DE JANEIRO (Município). Decreto nº 54.071, de 24 de maio de 2024. Institui o Programa de Monitoramento Contínuo da Cobertura Vegetal do Município do Rio de Janeiro e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial do Município do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 27 maio 2024.

RUFFATO-FERREIRA, V. J. Uma Nova Variável no Planejamento para o Desenvolvimento Urbano Sustentável: Áreas Verdes em Quintais no Subúrbio da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro. Tese (Planejamento Energético) – UFRJ/COPPE/Programa de Planejamento Energético, 2016.

SILVEIRA, C. et al. The Importance of Private Gardens and Their Spatial Composition and Configuration to Urban Heat Island Mitigation. Sustainable Cities and Society, v. 112, [S.n.], 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.scs.2024.105589.

TEIXEIRA, R. F. R. Identificação e caracterização de áreas verdes urbanas da região administrativa da Penha (XI): Uma análise comparativa de sensores. Rio de Janeiro. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Geografia) – Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2025.

THEANO, S.; TSITSONI, T. The effects of vegetation on reducing traffic noise from a city ring road. Noise Control Engineering Journal, v. 59, n. 1, 2011. DOI: 10.3397/1.3528970

TRIMBLE. eCognition Developer 9.0: Reference Book. Munich: Trimble Germany GmbH, 2014.

WEHR, A; LOHR, U. Airborne laser scanning: an introduction and overview. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, v. 54, n. 2-3, 1999. DOI: 10.1016/S0924-2716(99)00011-8

YANG, J. et al. The temporal trend of urban green coverage in major Chinese cities between 1990 and 2010. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, v. 13, n. 1, 2014. DOI: 10.1016/j.ufug.2013.10.002

About the Authors

Felipe Gonçalves Amaral holds a PhD, Master’s, and Bachelor’s degree in Geography from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), as well as a Bachelor’s degree in Mathematical and Earth Sciences from the same institution. He is currently a postdoctoral researcher in Geography (UFRJ) and a substitute professor in the Department of Geography (UFRJ).

Evelyn de Castro Porto Costa is a postdoctoral researcher in Geography (UFRJ). She holds a PhD in Geography from the Federal Fluminense University (UFF), a Master’s degree in Geography from the State University of Rio de Janeiro – Faculty of Teacher Education (UERJ/FFP), a teaching degree in Geography from UERJ/FFP, and a Bachelor’s degree in Geography from UFF. She is currently an associate professor in the Department of Geography Teaching of the Institute of Geography at the State University of Rio de Janeiro – Cabo Frio Campus (UERJ/CF).

Patrícia Luana Costa Araújo is a PhD candidate and holds a Master’s degree in Geography from UFRJ, and a Bachelor’s degree in Architecture and Urbanism. She is currently a substitute professor in the Department of Geography at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

Steffi Munique Damasceno dos Reis Vieira is a Master’s student in Geography at UFRJ. She holds both a Bachelor’s and a teaching degree in Geography from the Federal Fluminense University (UFF).

Amanda Lago de Souza Lugon holds a Bachelor’s degree in Geography from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and is currently pursuing a Master’s degree and a teaching degree in Geography at the same institution.

Mayara do Nascimento Ramos holds a teaching degree in Geography from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and is currently pursuing a Master’s degree and a Bachelor’s degree in Geography at the same institution.

João Victor Ladeira Silva is an undergraduate student in Geography Teaching at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and a CNPq scholarship holder.

João Victor da Silva dos Santos is an undergraduate student in Geography (Bachelor’s degree) at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

Rafael Ferreira Rodrigues Teixeira holds a Bachelor’s degree in Geography from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

Laura da Silva Bianchini is an undergraduate student in Geography (Bachelor’s degree) at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

Matheus Augusto de Souza is an undergraduate student in Mathematical and Earth Sciences at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), with an emphasis on Remote Sensing and Geoprocessing.

Carla Bernadete Madureira Cruz is a cartographic engineer and full professor in the Department of Geography at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). She is a CNPq Research Productivity Fellow – Level C and a “Scientist of Our State” (FAPERJ).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: [F.G.A., P.L.C.A.]; methodology: [F.G.A., A.L.S.L., M.N.R., R.F.R.T., M.A.S.]; software: [A.L.S.L., M.N.R.]; formal analysis: [F.G.A., P.L.C.A., A.L.S.L., M.N.R., R.F.R.T., M.A.S., J.V.L.S., J.V.S.S., L.S.B., S.M.D.R.V.]; investigation: [F.G.A., P.L.C.A., A.L.S.L., M.N.R., E.C.P.C.]; resources: [F.G.A., C.B.M.C.]; data curation: [F.G.A., P.L.C.A., A.L.S.L., M.N.R., E.C.P.C.]; writing—original draft preparation: [F.G.A.]; writing—review and editing: [F.G.A., P.L.C.A., E.C.P.C., S.M.D.R.V.]; visualization: [J.V.L.S., J.V.S.S., L.S.B.]; supervision: [F.G.A., C.B.M.C.]; project administration: [F.G.A., C.B.M.C.]; funding acquisition: [F.G.A., C.B.M.C.]. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Rio de Janeiro State Research Support Foundation (FAPERJ), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), through research funding, and the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), through undergraduate research, master’s, doctoral, and postdoctoral scholarships.

In addition, this article is linked to and received funding from the following projects:

- FAPERJ Call No. 17/2024 – Postdoctoral Fellowship Nota 10 (PDR-10);

- FAPERJ Call No. 32/2021 – Scientist of Our State Program (2021);

- FAPERJ Call No. 22/2025 – Pensa Rio Program: Support for the Study of Relevant and Strategic Topics for the State of Rio de Janeiro (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the Graduate Program in Geography and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) for providing the physical space necessary for the development of this research. They thank the ESPAÇO Laboratory for enabling the collaboration of different academic profiles that contributed to the preparation of this article.

They also thank the Rio de Janeiro State Research Support Foundation (FAPERJ), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) for research funding. Finally, they thank the Municipal Institute of Urbanism Pereira Passos (IPP) for providing the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

About Coleção Estudos Cariocas

Coleção Estudos Cariocas (ISSN 1984-7203) is a publication dedicated to studies and research on the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, affiliated with the Pereira Passos Institute (IPP) of the Rio de Janeiro City Hall.

Its objective is to disseminate technical and scientific production on topics related to the city of Rio de Janeiro, as well as its metropolitan connections and its role in regional, national, and international contexts. The collection is open to all researchers (whether municipal employees or not) and covers a wide range of fields — provided they partially or fully address the spatial scope of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Articles must also align with the Institute’s objectives, which are:

- to promote and coordinate public intervention in the city’s urban space;

- to provide and integrate the activities of the city’s geographic, cartographic, monographic, and statistical information systems;

- to support the establishment of basic guidelines for the city’s socioeconomic development.

Special emphasis will be given to the articulation of the articles with the city's economic development proposal. Thus, it is expected that the multidisciplinary articles submitted to the journal will address the urban development needs of Rio de Janeiro.